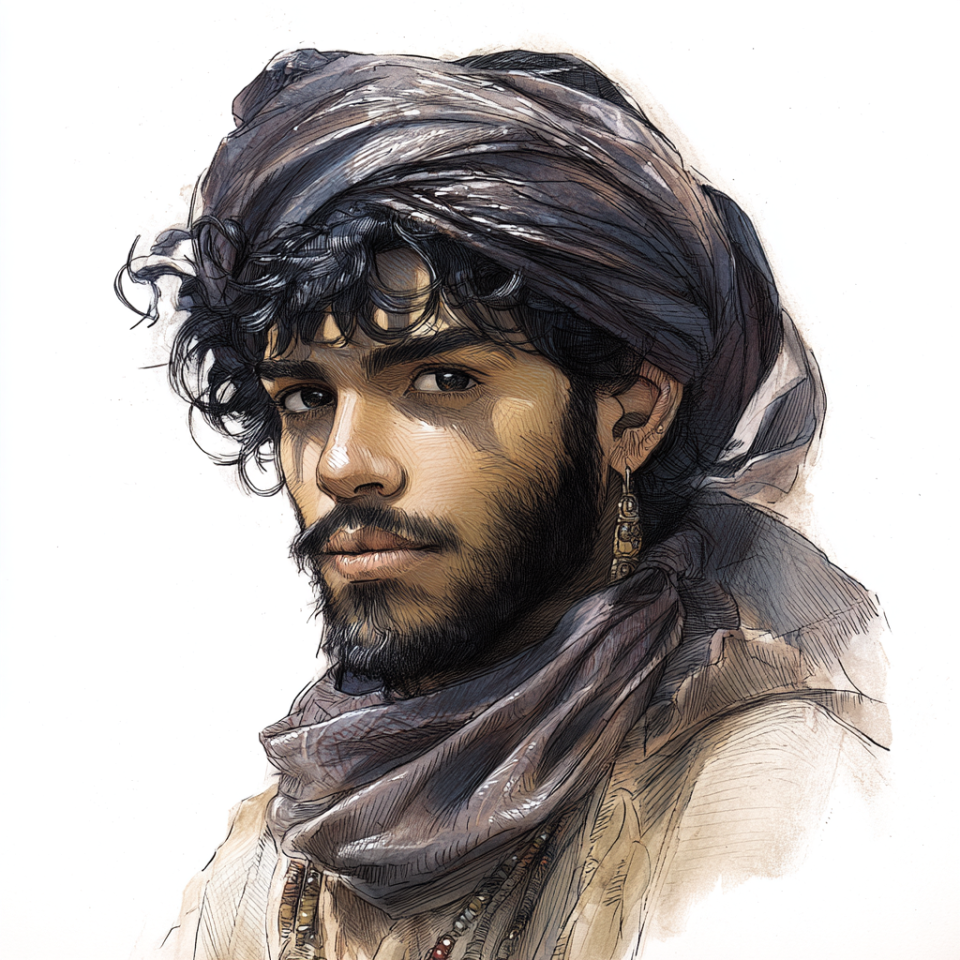

Darien Vashti (DAH-ree-en VASH-tee)

Master of Photography — Keeper of Light Impressions

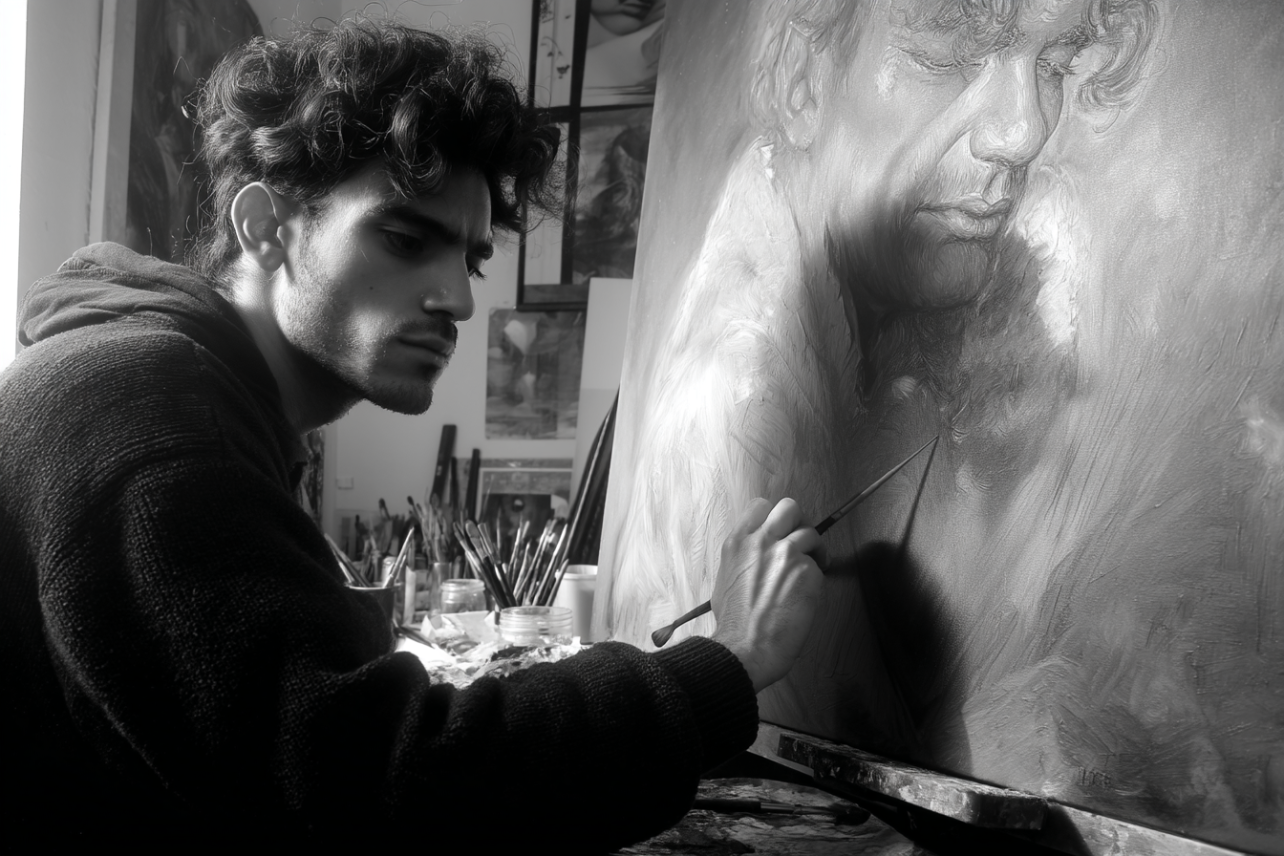

On a cliff edge in the Zāgros at dawn, Darien Vashti waited for the sun to rise. His camera — a ceramic box lined with polished copper, fitted with a lens ground from river quartz — stood poised like a shrine. When the first light spilled over the ridges, he pulled the plate from its case, and the mountain inscribed itself upon it. “Not a picture,” he would tell students who gathered around him, “but the mountain’s own memory.”

Born among the nomadic families of the Zāgros, Darien’s earliest lessons were not in classrooms but in landscapes. His childhood horizon was never fixed: cedar forests, desert plateaus, glacial springs, and caravan roads became his teachers. From his Romani forebears he inherited the rhythms of music and story; from the Persian valleys he absorbed reverence for stone, light, and silence.

Apprenticeship took him through many guilds — scribes, alchemists, artisans — but he never stayed long. It was among the chemical artisans of Antioch that he discovered the first light-sensitive mineral emulsions, and it was on the road with traveling translators that he carried this craft to its fullest expression. While others dreamed of documenting portraits, Darien refused. “People change too quickly,” he would say. “The mountains do not lie.” His work became a hymn to the natural world: jagged ridges rendered in stark contrasts, deserts caught in infinite gradations of shadow, rivers frozen mid-song in silver on clay.

Darien’s romantic life mirrored his art — passionate, fleeting, always in motion. Lovers in Antioch, Alexandria, Nalanda, and the high valleys of the Andes remembered him not for permanence but for intensity. He embraced pansexual bonds without label or claim, seeing every encounter as another landscape to be cherished, not owned. His only constancy was the road, and the camera he built to carry it.

By the mid-13th century, Darien’s “light impressions” had become widely known. His plates traveled as gifts through caravan guilds, finding their way into council halls and shrines far beyond his own hand. The Translator Guilds, recognizing the universal language of his work, curated his landscapes as some of the first visual archives in the Net of Voices. His philosophy was simple yet enduring: “To photograph is to preserve balance twice — once in the world, and once in the memory we share.”

Comments