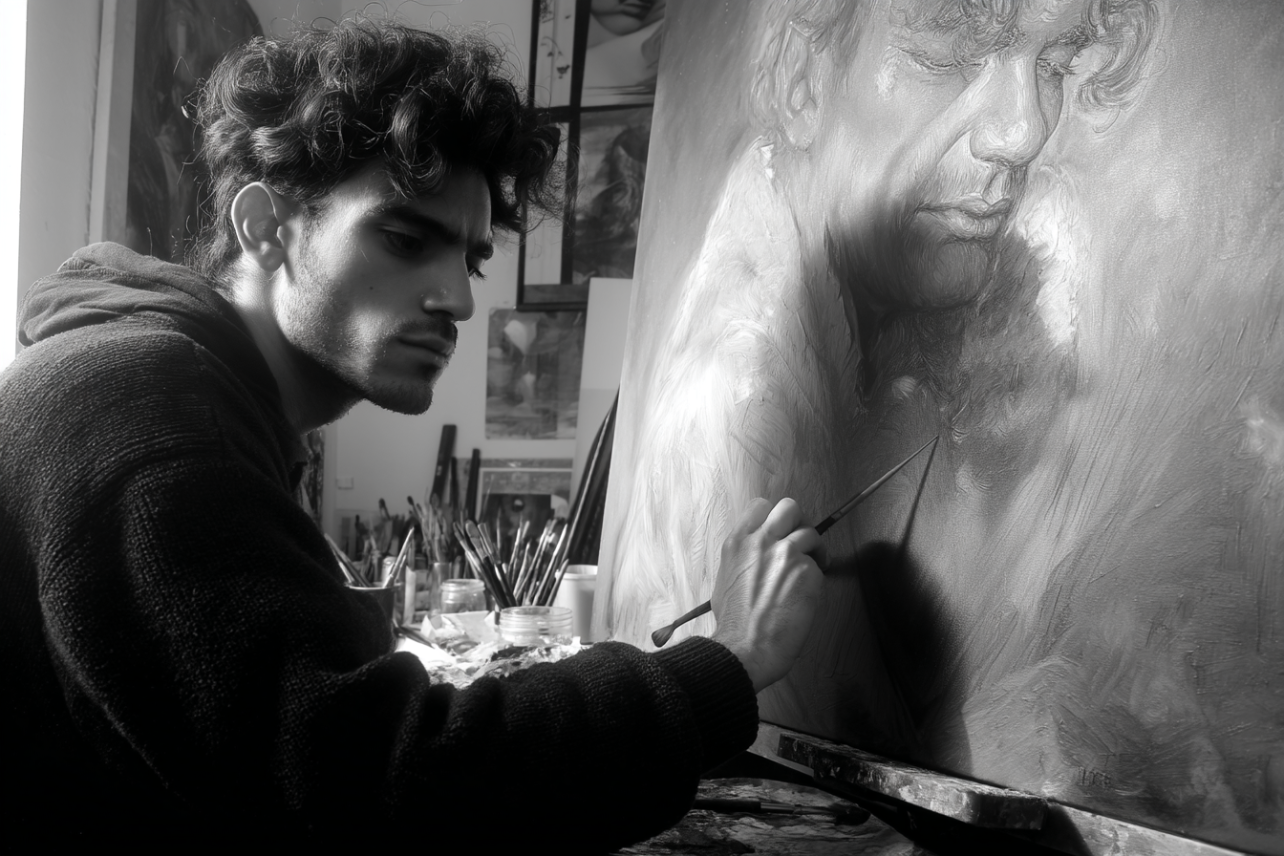

Amir Qadir al-Rashid (ah-MEER kah-DEER)

The Master of Resonance and Form

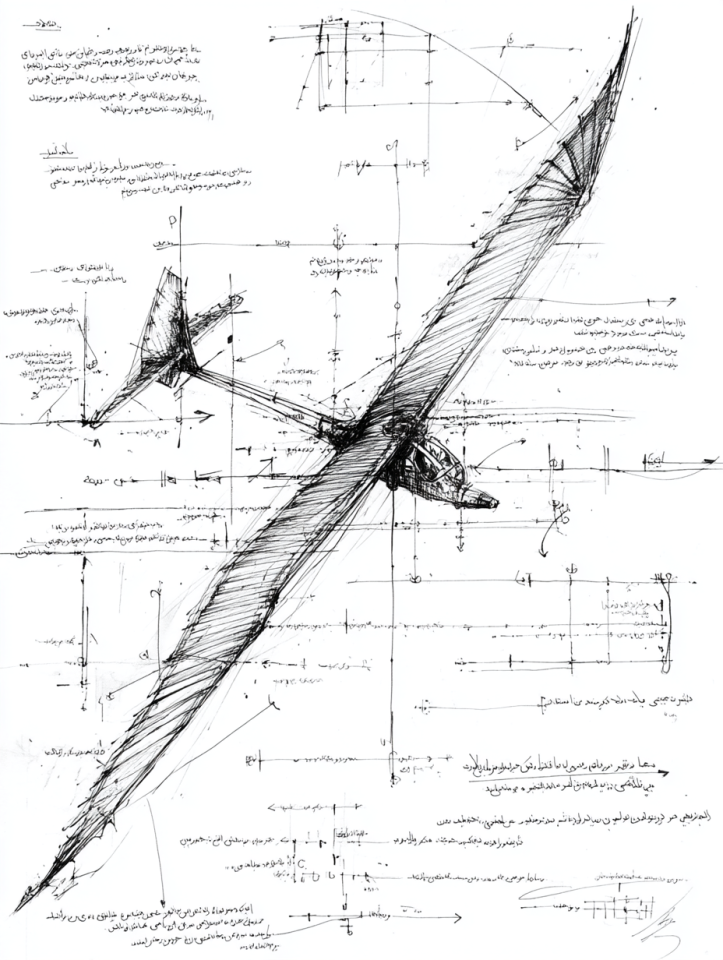

In a hall where guildsmen argued over contracts and priests debated the divine, Amir Qadir al-Rashid sketched wings across the margins of his notes. To his students he was both mentor and torment, demanding they study astronomy in the morning and anatomy by lamplight at night. His rooms overflowed with codices, gears, pigments, bones, and birds’ feathers — yet from this chaos came order, and from order, visions that would alter centuries.

Biography

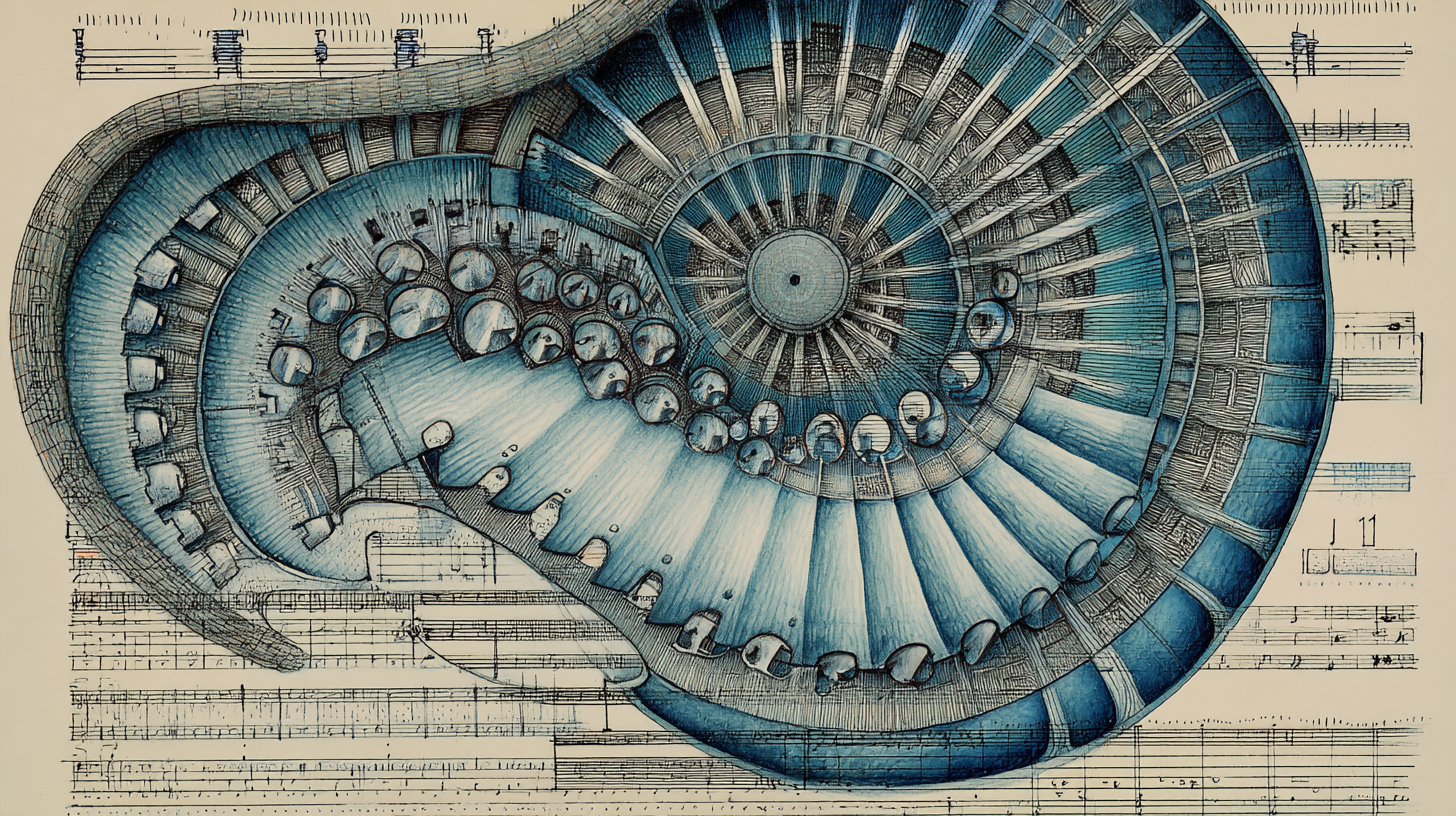

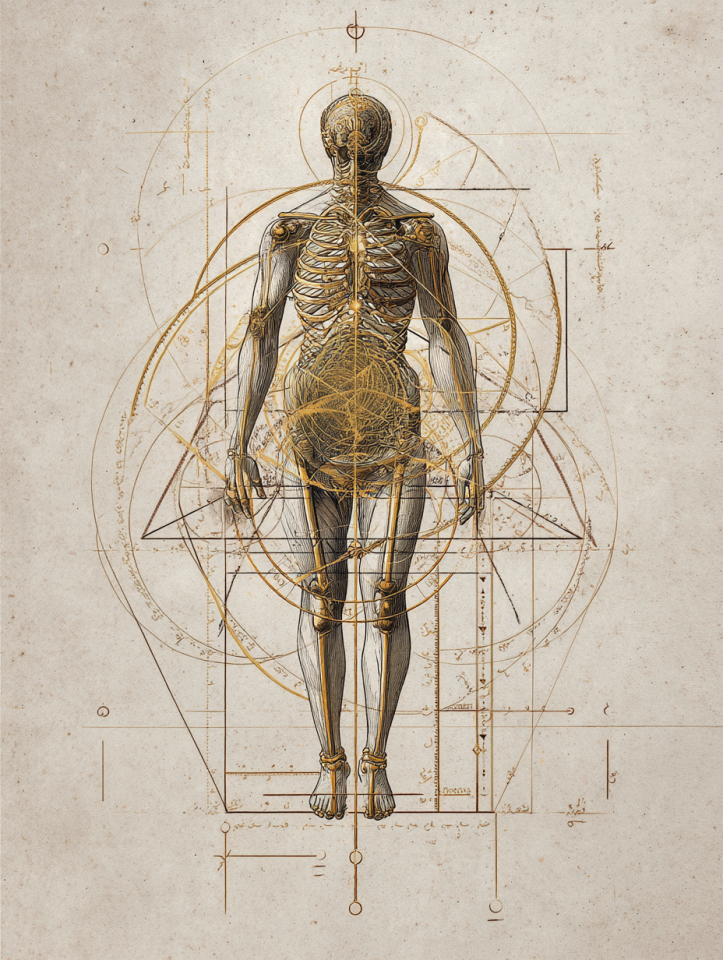

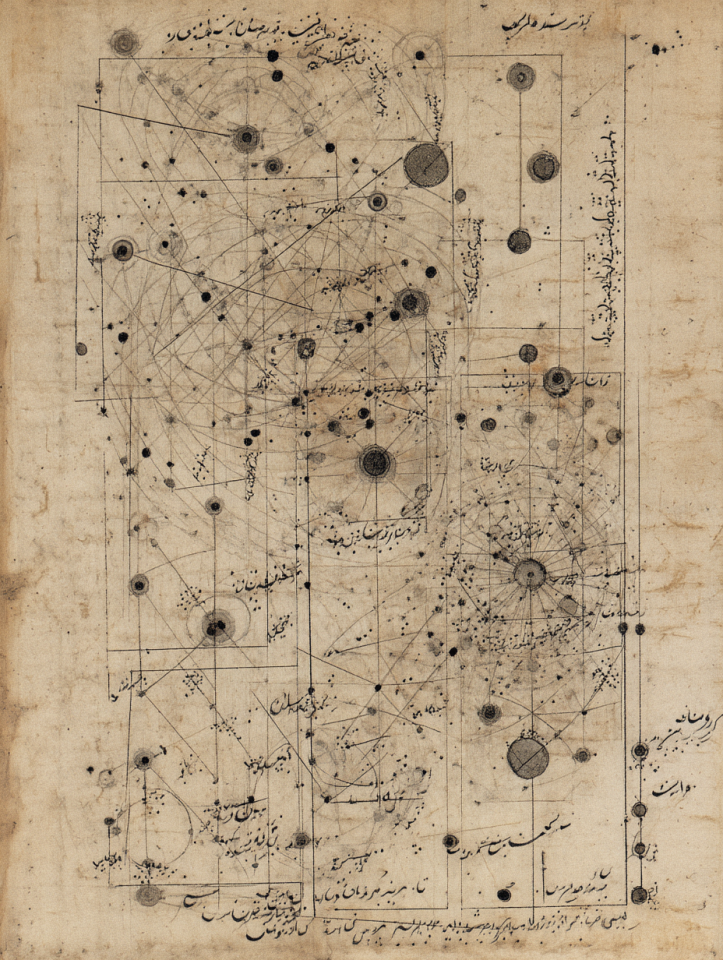

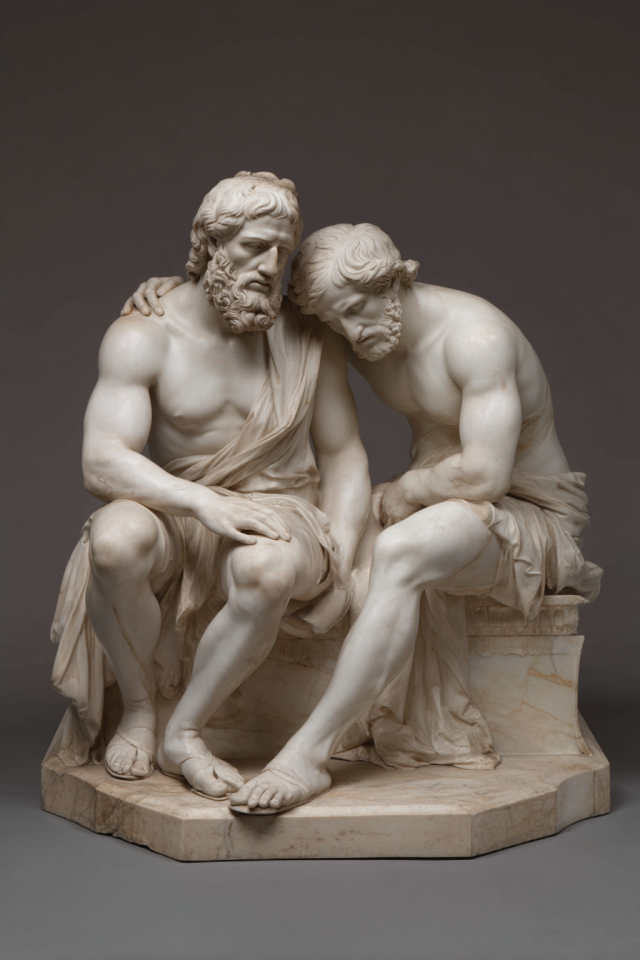

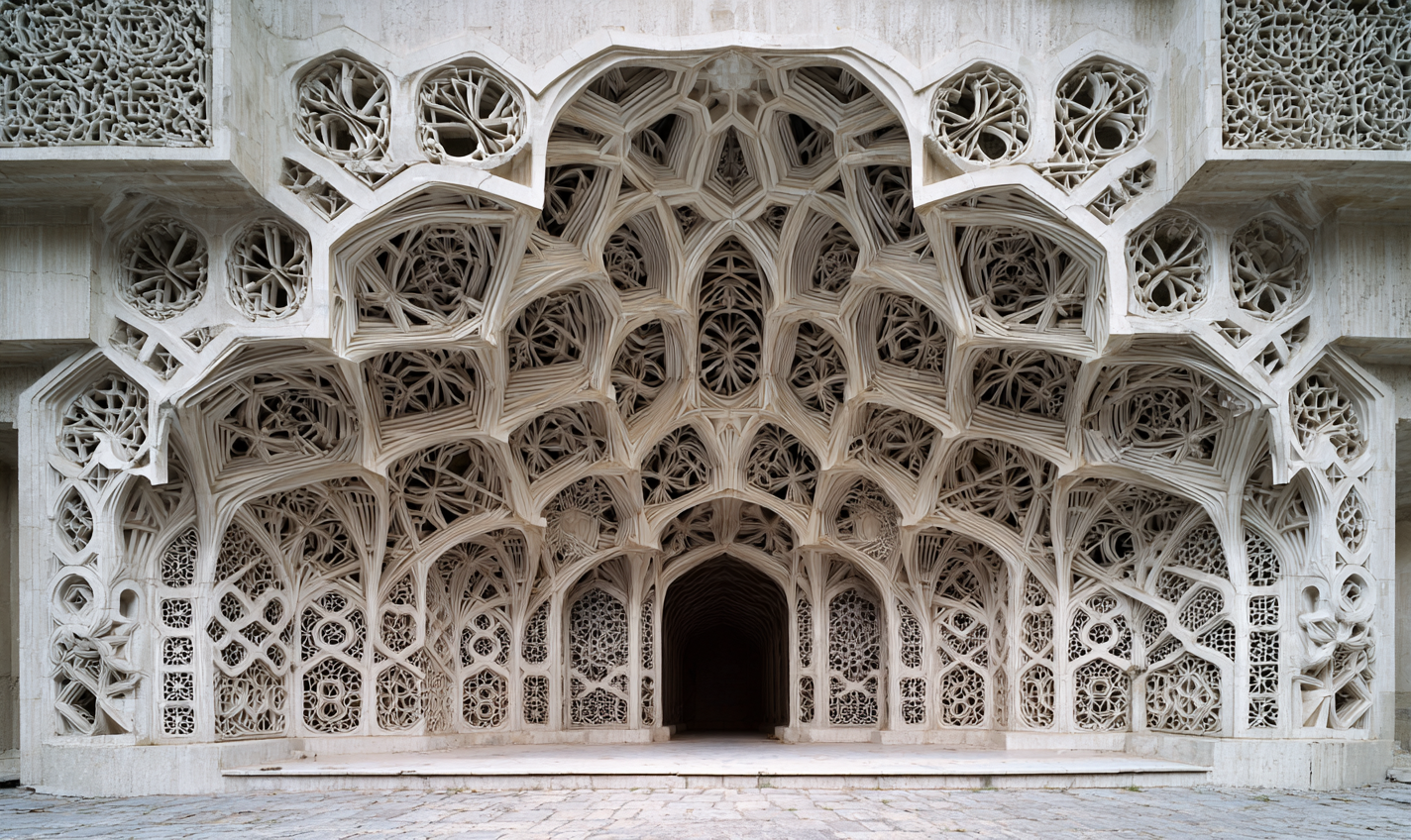

Amir was born in Isfahan into a family of scribes and mathematicians. From an early age he exhibited a restless curiosity that refused boundaries. Where his peers learned calligraphy, Amir dissected birds to understand flight. Where others memorized scripture, he covered margins with diagrams of wheels and pulleys. His parents, recognizing both danger and promise, apprenticed him first to a physician, then to an engineer, though none could fully contain his appetite for knowledge. As a youth, Amir studied under traveling scholars from across the federations. He absorbed Greek philosophy, Indian mathematics, and Chinese cosmology, weaving them into his own restless synthesis. By twenty, he had produced anatomical sketches of such precision that physicians copied them for reference. Yet he also painted landscapes with startling realism, pioneering the use of vanishing perspective in miniature painting. To contemporaries, he seemed torn between arts and sciences; to Amir, they were inseparable. His first great project was the Codex of Forms, a sprawling manuscript of drawings, notes, and resonant experiments. Within its pages were gliders shaped like swans, harmonic water organs, sketches of human musculature, and city plans based on ecological circulation. The codex revealed not a single vision but an entire universe of interlinked ideas. Though many dismissed it as fanciful, apprentices flocked to his workshop to witness his relentless experimentation. In 1207, Amir founded the House of Resonant Arts in Samarkand. There, mathematics was taught beside poetry, sculpture beside astronomy. Students built scale models of machines, composed music based on geometric ratios, and debated philosophy beneath vast diagrams painted on walls. The House became a magnet for talent across the cooperative world, and its graduates spread his ideas into countless disciplines. Amir, both demanding and affectionate, guided them with a mix of ferocity and humor, often destroying their first works to force them toward deeper understanding. Despite his brilliance, Amir was not always easy to live with. He was known to abandon commissions halfway through, chasing a new idea that struck him at dawn. Patrons alternately revered and despised him: councils competed for his presence, yet none could hold him long. His refusal of permanent patronage became a statement of independence — he would serve federations but never be owned by them. This stubbornness earned him both enemies and legendary stature. Amir’s personal life was as unconventional as his work. He was openly bisexual and known for his simultaneous relationships with patrons, apprentices, and guildmasters. While controversial, his circle protected him, seeing his loves as extensions of his philosophy: that creation itself required union and plurality. His companions often became collaborators, and the House of Resonant Arts sometimes seemed as much a salon of lovers as of students. Gossip abounded, but Amir made no apologies, insisting that “truth in form comes only from truth in living.” His later works grew increasingly ambitious. He designed gliders that briefly carried apprentices across courtyards, experimented with resonance chambers that magnified human voice into choral tones, and drafted city plans where water, wind, and light flowed in ecological balance. Though many of these remained prototypes, their influence stretched centuries ahead. More than once, his sketches were rediscovered and applied long after his death, giving him the aura of prophecy. Amir’s final years were marked by both brilliance and decline. He contracted a venereal disease in his late sixties, but so consumed was he by invention and teaching that he neglected treatment. Friends and students pleaded with him to rest, yet he continued working, even as his body weakened. He was last seen lecturing with chalk-stained fingers, coughing blood onto his notes as he explained the geometry of bird wings. On 3 November 1255, at the age of 75, he collapsed in Samarkand, surrounded by apprentices who swore they could still hear his voice echoing in the resonance chambers he had designed.Legacy

Though his life ended in frailty, Amir Qadir al-Rashid’s influence only grew. His Codex of Forms became a foundational text for generations of artisans, inventors, and philosophers. The House of Resonant Arts continued for centuries, producing polymaths in his image. His sketches of flight, resonance, and ecological planning would be revived in later ages, proving his vision timeless. Remembered as the Master of Resonance and Form, Amir remains the archetype of the cooperative genius: brilliant, unruly, scandalous, and utterly transformative.

Date of Birth

14 Maat 1180 zc (Shifa)

Date of Death

07 Fjölgjǫf 1255 zc (Reposo)

Life

1180 zc

1255 zc

75 years old

Circumstances of Death

Succumbed to an untreated venereal disease in his mid-70s; so consumed with teaching, invention, and his many relationships that he neglected his health until it was too late.

Birthplace

Isfahan, Pārsa

Place of Death

Samarkand, Pārsa

Children

Belief/Deity

Other Affiliations

Comments