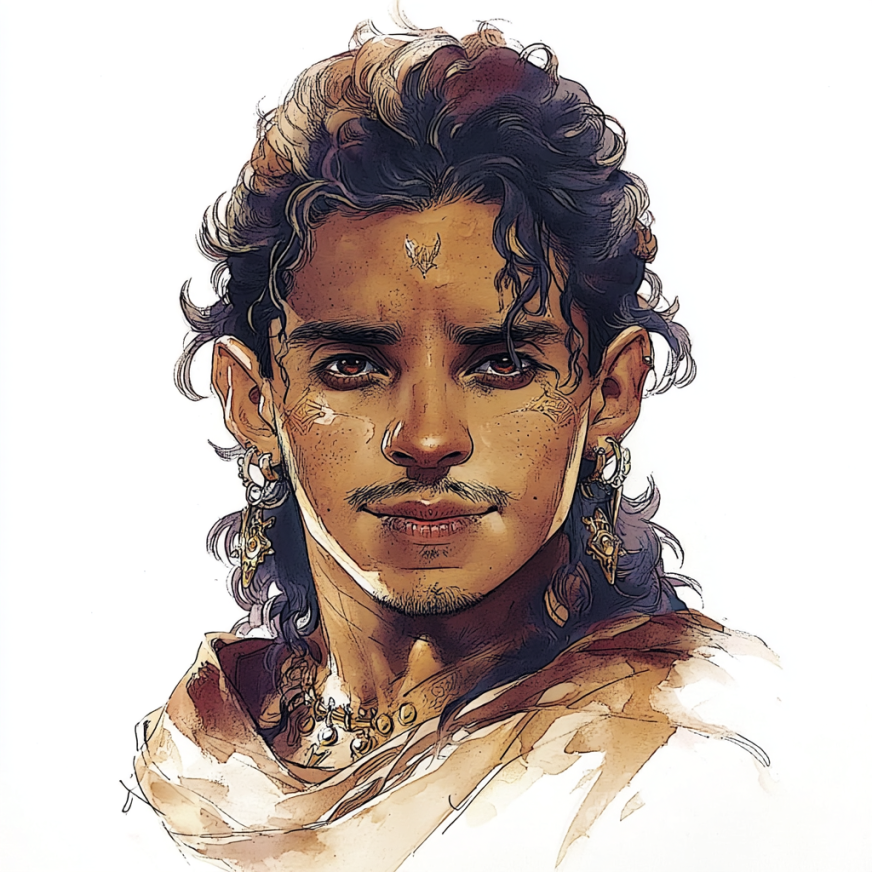

Ashoka of Pataliputra (ah-SHOW-ka)

First Voice of Āryāvarta

(a.k.a. Bohdi)

Ashoka, later known by his affectionate nickname “Bodhi,” was born in the great city of Pataliputra, the beating heart of the Mauryan Empire. The son of a respected scholar and a midwife, Ashoka grew up surrounded by the intellectual ferment of the imperial court. Unlike many of his peers, who trained for administrative roles or the army, Ashoka was drawn to the meditative practices of the Buddhists and the logical reasoning of Jain and Vedic schools. His sharp mind and youthful confidence made him a curiosity in courtly circles — a boy who questioned authority with disarming honesty, yet always with respect.

By his early teens, Ashoka was already recognized as a gifted orator and philosopher. Teachers noted his unusual ability to translate complex metaphysical questions into simple, vivid analogies, a skill that won him audiences among both monks and artisans. His nickname “Bodhi,” meaning awakening or enlightenment, was first given by a group of Buddhist teachers who saw in him a seeker’s heart, though Ashoka himself resisted formal religious allegiance. Instead, he spoke of philosophy as a universal path to harmony.

At the time of the near-disaster at Alexandria, Ashoka was only eighteen, yet he was chosen as the Mauryan delegate to Antioch for a daring reason: his youth represented the future. The Emperor’s councilors believed that a voice unbound by the rigid hierarchies of age and status might offer fresh insight. Bodhi did not disappoint. At the signing of the Accord, he reportedly said, “If knowledge is a flame, then let us be its lamps, not its owners.” His sincerity and clarity of vision impressed older delegates, who came to see him as both a symbol and a conscience of the gathering.

After the Accord, Bodhi continued to serve as a teacher, traveling across India to spread the ideals of preservation, compassion, and reason. He never married, dedicating his short life to dialogue and mentorship. Though he died tragically young at twenty-six, his writings and remembered sayings became touchstones for later generations. His role in the Accord remains one of history’s most poignant reminders that wisdom need not wait for age.

Comments