Isolde Marcellina of Amalfi (ee-SOHL-deh mar-cheh-LEE-nah)

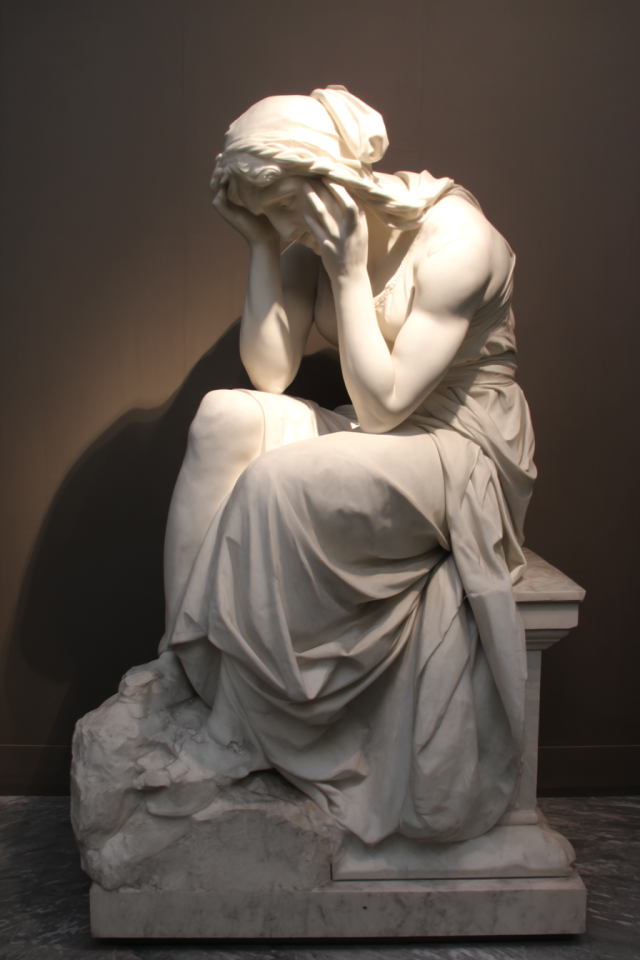

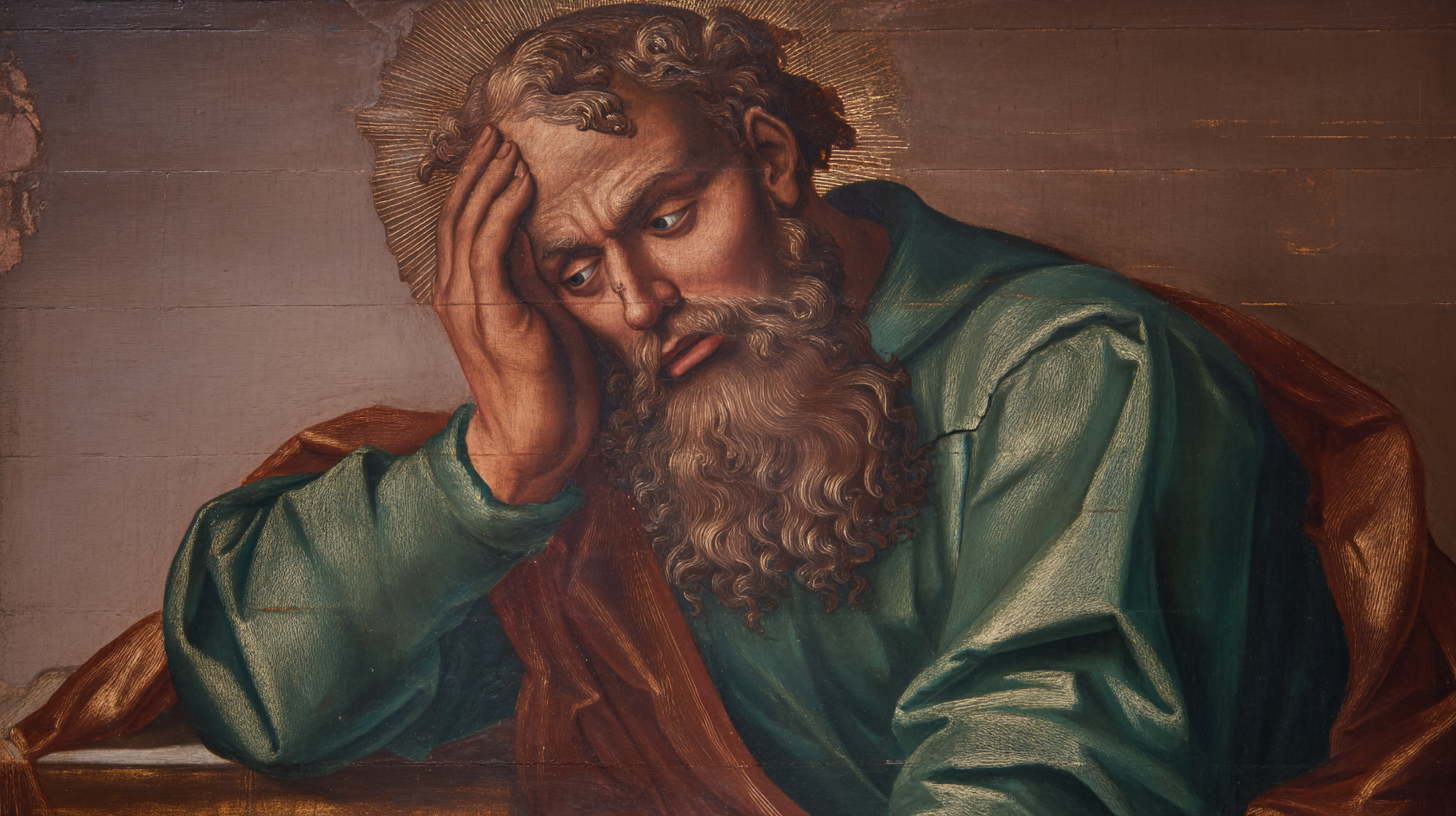

The Mother of Monumental Emotion

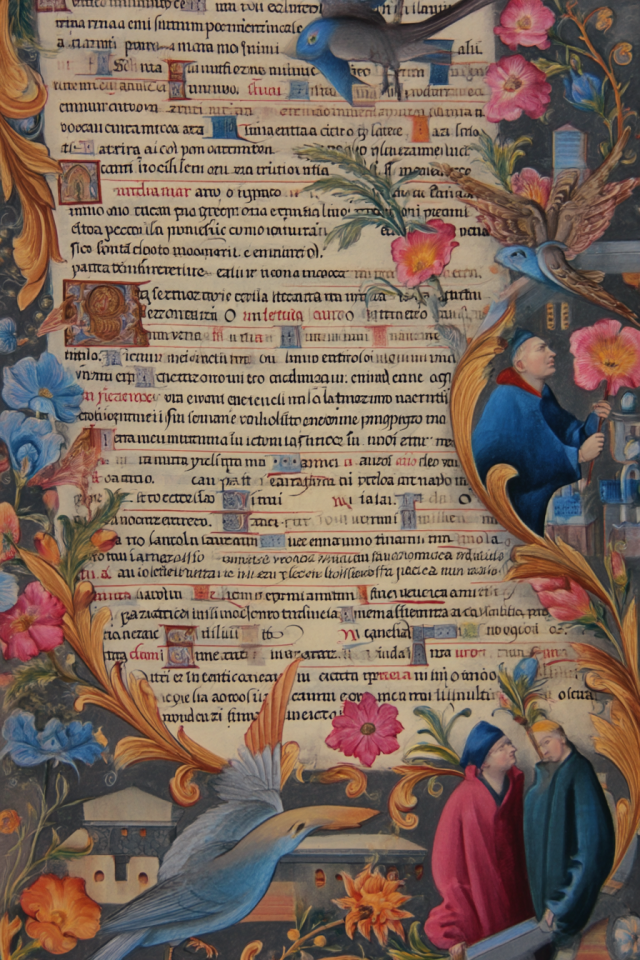

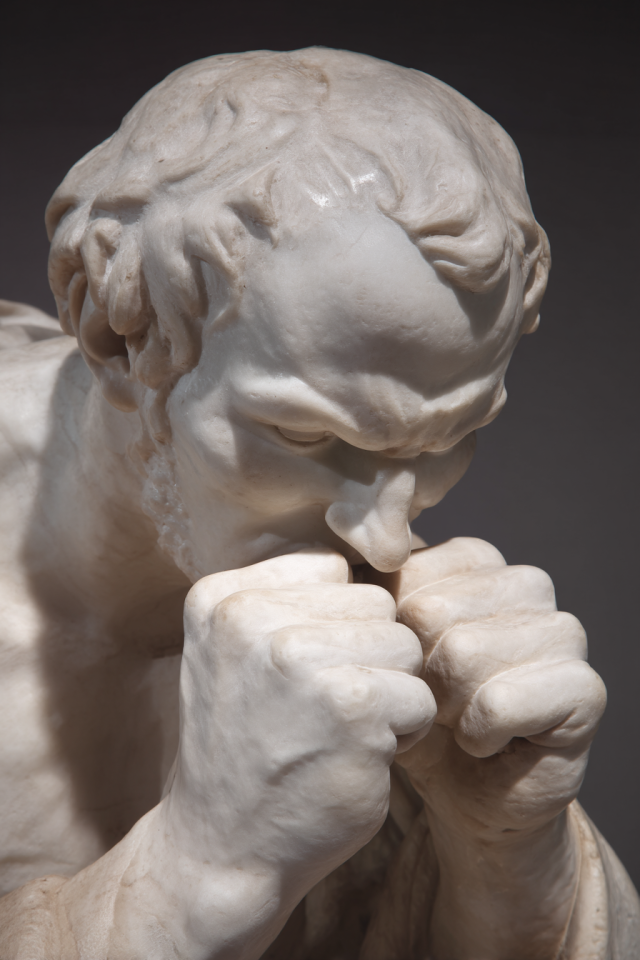

When Isolde struck marble, the sound echoed like thunder. Apprentices swore she could see the figure inside the stone before she touched it, and patrons both feared and adored her temper. She painted saints with eyes of grief, carved women with shoulders like mountains, and composed sonnets sharp enough to wound. In her studio, plaster dust mingled with wine, and her lovers — men and women alike — recited poetry in turns.

Biography

Isolde was born the daughter of a merchant family whose wealth allowed her a childhood surrounded by imported silks, manuscripts, and foreign voices. She showed early talent for drawing, carving toys from driftwood and sketching portraits of sailors who passed through her family’s port. When she demanded entry to guild workshops, her father used his influence to secure apprenticeships that would normally have been closed to women. She quickly proved she was no novelty: by her teenage years, she was already outstripping her instructors. Her early works were devotional paintings and frescoes for coastal chapels. Though small in scale, they bore a striking emotional intensity. Saints were not depicted in serene detachment but in states of anguish, doubt, or rapture. Parishioners reportedly wept before her altarpieces. By her twenties, she had turned to sculpture, and it was in marble that her genius fully unfurled. Her figures were larger-than-life, rippling with muscle, or trembling with passion, their poses unflinchingly human. Where her contemporaries sought idealized beauty, Isolde sought truth in raw emotion. Her rise was meteoric. By thirty she was receiving commissions from federations and guild councils. Civic statues, monumental fountains, and allegorical reliefs poured from her workshop. Unlike many masters who relied on teams to execute their visions, Isolde insisted on shaping the most vital parts herself — faces, hands, torsos. She worked until her fingers bled, often shouting at assistants who failed to meet her impossible standards. Her workshop became both feared and revered, a crucible of sweat and brilliance. Isolde also excelled in painting and poetry. She produced a series of frescoes that celebrated maritime trade, drawing on Amalfi’s heritage, and a cycle of portraits of her lovers, each imbued with sensual tenderness rarely seen in public art. Her sonnets circulated widely, sometimes scandalizing with their overt references to passion between women. She was unapologetic, stating bluntly: “If marble may embrace both man and woman, why should I not?” Her private life was as legendary as her art. Isolde was openly bisexual and polyamorous, maintaining relationships with poets, noblewomen, fellow artisans, and guildmasters alike. She celebrated her loves in her art, immortalizing them in stone or verse. Though this scandalized conservative factions, her fame protected her, and her patrons were often among her companions. Her studio became not only a workplace but a salon where passion and creativity intertwined, an atmosphere both intoxicating and dangerous. She was also a political figure, though reluctantly so. Guild councils sought her endorsement, knowing her works could sway public sentiment. She once abandoned a commission for a powerful council when they attempted to dictate the design, redirecting her efforts to a rival federation’s plaza. This defiance made her enemies but also cemented her independence. She was, in every sense, uncontrollable — a force who would not bend to the dictates of authority. In her later years, Isolde increasingly took on apprentices, many of them women, whom she mentored with fierce devotion. She believed the guild system suffocated female talent and sought to create a lineage of artisans who would continue her legacy. Some of her pupils went on to found studios of their own, spreading her influence across the Mediterranean. Her studio became a rare space where women could carve, paint, and create without apology. Her final major work was a colossal civic statue in Florence, depicting a figure of Justice not as serene but as fierce and muscular, striding forward with scales outstretched. While overseeing its completion, Isolde collapsed suddenly on the scaffolding, shouting orders until her last breath. She was 65. Her apprentices, devastated, finished the statue in her honor.Legacy

Isolde Marcellina is remembered as the Mother of Monumental Emotion, a woman who carved passion into marble and painted grief onto walls. Her art remains arresting not because of its idealized forms but because it captures the tumult of human life — love, rage, devotion, loss. She transformed studios into sanctuaries for women and lovers into muses, and her colossal works still tower in civic plazas. More than a master of form, she was a master of feeling, immortalized in every chisel mark and every line of verse.

Date of Birth

08 Sophia 1460 zc (Dao)

Date of Death

24 Eirene 1525 zc (Shifa)

Life

1460 zc

1525 zc

65 years old

Circumstances of Death

Collapsed suddenly while shouting orders atop scaffolding for a monumental civic statue. She died as she lived: commanding, passionate, and in the midst of creation.

Birthplace

Amalfi, Italy

Place of Death

Florence, Federation of the Arno

Children

Belief/Deity

Other Affiliations

Comments