Citlali Teocuani (seet-LAH-lee teh-oh-KWAH-nee)

The Two-Spirit Master of Stone and Stars

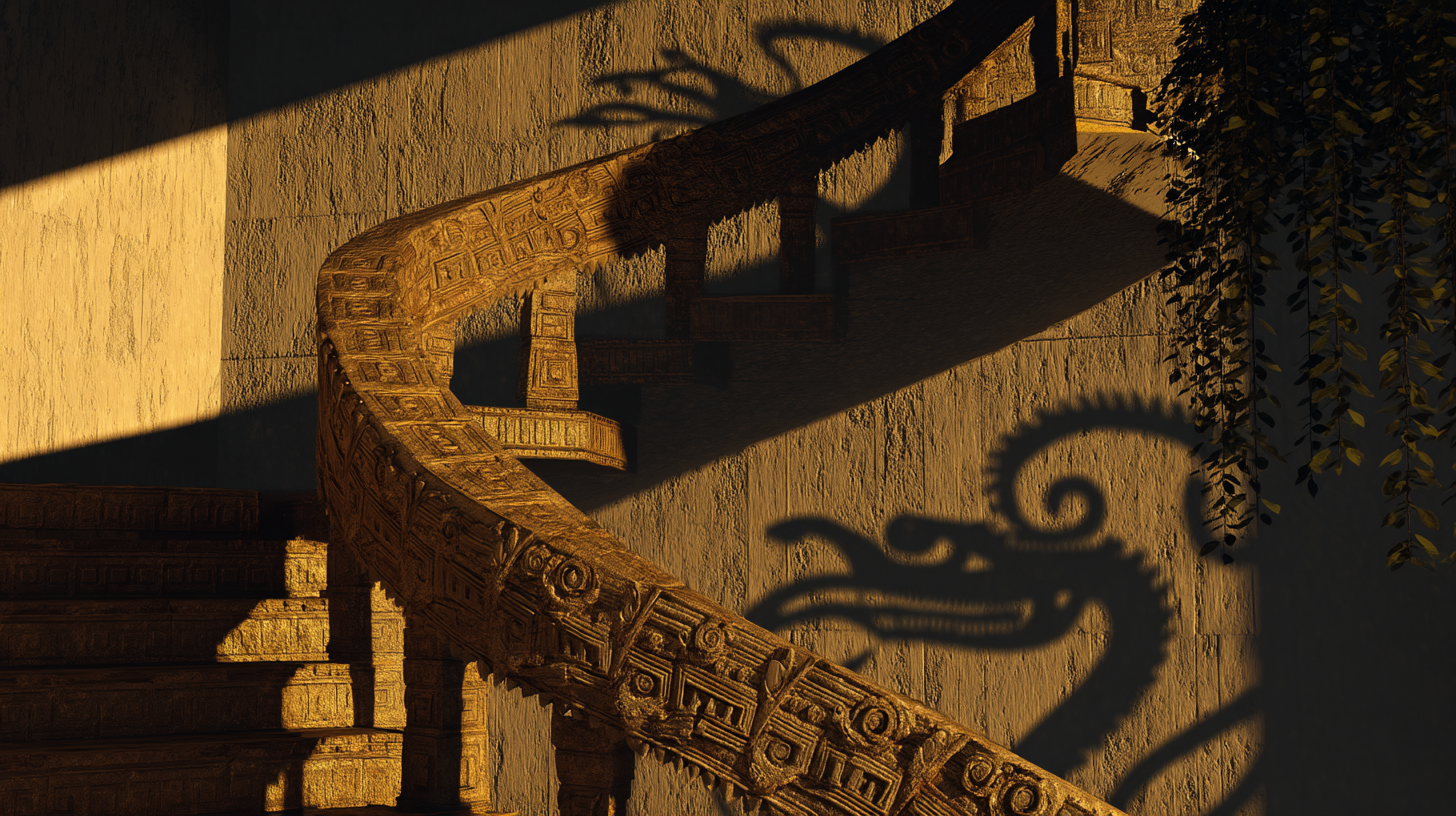

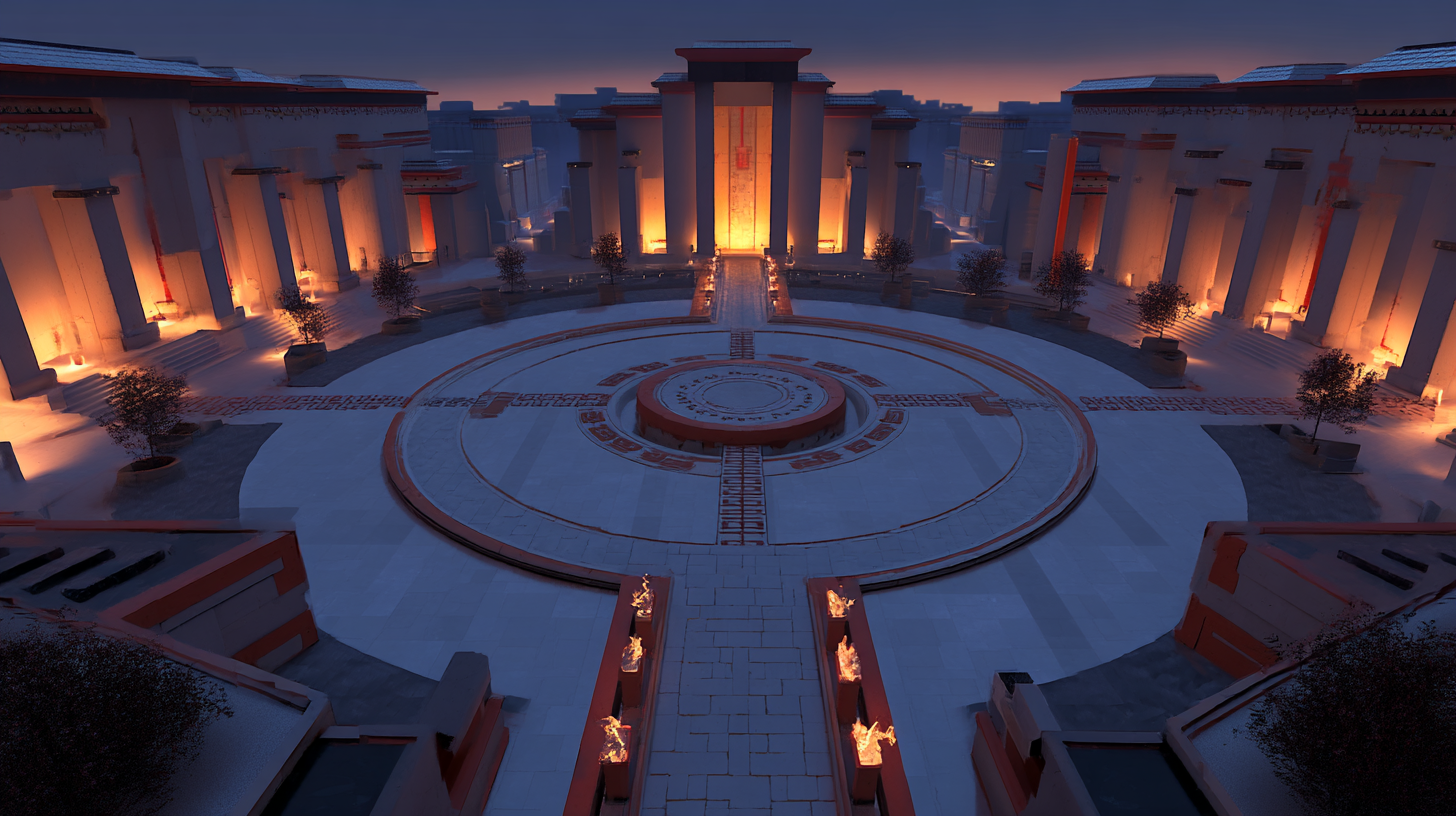

To walk through Citlali’s plazas was to step into a living calendar. Their temples breathed with mathematics, their stairways echoed with solstice light, and every stone they set carried a dialogue between earth and sky. Apprentices described them as austere but luminous — a figure who seemed more devoted to constellations than to human praise.

Biography

Citlali was born in the Oaxaca Valley, at a time when federations were experimenting with civic identity and architectural grandeur. Their family belonged to a lineage of stonemasons who traced their craft back to the builders of Monte Albán. From childhood they showed an unusual ability to memorize star patterns and to reproduce them with pebbles and chalk. Their community recognized this gift as a sign of balance, embracing Citlali’s Two-Spirit identity as an embodiment of harmony between realms. Apprenticed at age ten, Citlali spent long days learning to quarry stone, carve lintels, and set foundations. Yet in the evenings they climbed hills to observe the heavens, sketching how constellations shifted with the seasons. By their teens they were already proposing designs that aligned temples with solstice sunrises and civic plazas with lunar phases. Masters alternately dismissed these ideas as fanciful or proclaimed them visionary. Citlali themselves seemed unconcerned, driven less by approval than by the conviction that stone must speak to the stars. Their first major commission came in their twenties: a civic plaza in the Oaxaca highlands. Citlali designed it so that at equinox, the rising sun passed perfectly through a central arch, casting a line of light across the floor mosaic. Farmers soon used the plaza as a seasonal marker, planting and harvesting in rhythm with the shadow. The structure became both sacred and practical, an emblem of their philosophy that architecture must unite cosmology with daily life. Over the next two decades Citlali became renowned across Meso. They designed staircases that cast shadows resembling serpents, fountains that reflected lunar crescents, and observatory chambers whose doorways framed specific stars. Their projects were often monumental but never ornamental — every stone served both a symbolic and functional purpose. Unlike other architects who sought grandeur for its own sake, Citlali measured success by whether a plaza could teach farmers when to sow, or whether a temple aligned a community with the cosmos. Citlali’s personal life was marked by serenity and restraint. Though admired for their beauty and intensity, they rarely engaged in fleeting relationships. Instead, they formed a handful of profound bonds across their lifetime, each one nurtured over years of trust and companionship. Many described them as demiromantic and largely asexual, channeling their passion into architecture rather than physical desire. Yet their closest companions — apprentices, fellow philosophers, and occasionally patrons — spoke of a deep intimacy that transcended conventional categories. Their studio reflected this balance. Citlali demanded discipline: apprentices rose before dawn to chart the stars before carving stone. At the same time, they cultivated a spiritual atmosphere, leading meditations on geometry and reciting poems about the heavens. To work under Citlali was to inhabit a rhythm of sky and stone, body and cosmos. Many apprentices described their teaching as transformative, a discipline that reshaped not just craft but identity. Despite their fame, Citlali remained humble and detached from politics. They refused lavish commissions that prioritized spectacle, preferring projects that served communal life. This often put them at odds with wealthy patrons, but their reputation for cosmic precision made them difficult to ignore. In time, federations courted them not only as an architect but as a philosopher whose works embodied civic and spiritual balance. Their final years were spent at Teotihuacan, where they oversaw the restoration and expansion of ancient plazas. There, Citlali created their most ambitious project: a temple whose stairways aligned with the solstice and whose windows framed both Venus and the Pleiades. At the end, while supervising its construction, they collapsed from exhaustion. Apprentices later reported that the last words they uttered were: “The stars will finish what I cannot.”Legacy

Citlali Teocuani is remembered as the Two-Spirit Master of Stone and Stars — a visionary who bridged precolonial heritage and cooperative innovation. Their plazas remain living calendars, guiding rituals and harvests, and their temples are still studied for their astronomical precision. More than a builder, they were a philosopher of balance, embodying the union of heaven and earth, form and function, body and cosmos. In every stone they set, Citlali left a map to the stars.

Date of Birth

30 Yūgen 1782 zc (Fiesta)

Date of Death

07 Zhìdé 1844 zc (Reposo)

Life

1782 zc

1844 zc

62 years old

Circumstances of Death

Passed quietly in their sleep surrounded by loved ones.

Birthplace

Oaxaca Valley, Anahuac

Place of Death

Teotihuacan, Anahuac

Children

Belief/Deity

Other Affiliations

Comments