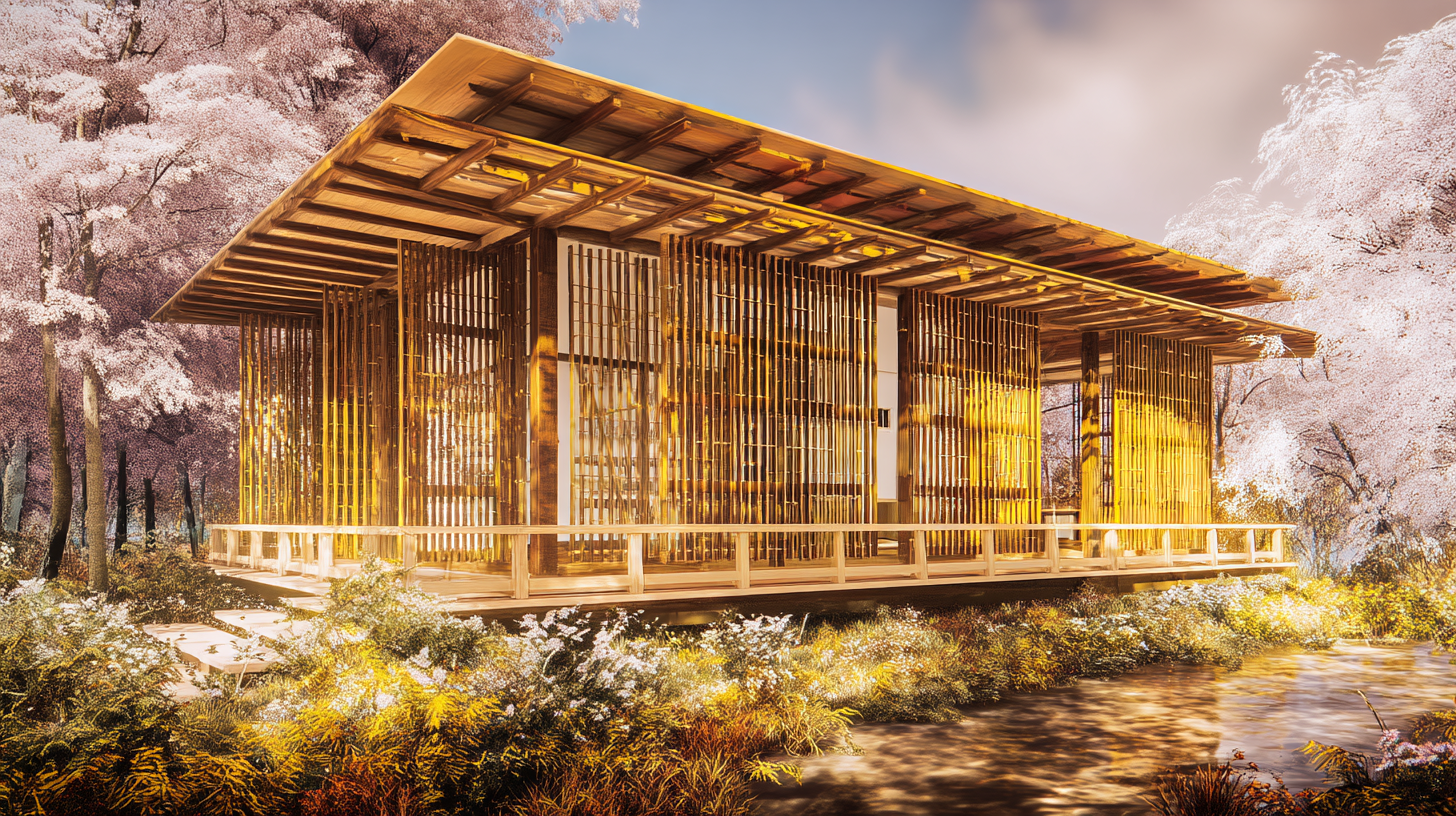

Aiko Takamura bent cedar and pine into forms that seemed to breathe. Her temples let light filter like water through slatted walls, her bridges arched as though grown from the landscape, and her pavilions opened to the wind as though to invite nature itself indoors.

Biography

Aiko was born into a family of carpenters and temple restorers. From an early age she absorbed the rhythms of joinery, shadow, and grain. Her grandfather, a master builder, taught her the sacred principles of timber architecture: that every cut must honor the spirit of the tree, and that buildings were not inert shelters but companions to human life. In this environment she developed not only technical skill but also a spiritual philosophy that would guide her entire career.

Her childhood was marked by the shifting world of early 20th-century Nihon, when Western modernism was arriving with steel and concrete. Many of her contemporaries embraced these new materials, but Aiko resisted the prevailing currents. Instead, she sought to prove that wood — flexible, renewable, alive — could carry modernity into the future. She began experimenting with unusual curves, slatted walls that filtered light like water, and modular structures that could be disassembled and rebuilt as though they themselves were seasonal.

By her twenties she was already known within Kyoto’s architectural circles for her ability to combine timeless aesthetics with practical innovation. Her first major commission, a riverside pavilion in Nara, revealed her signature style: open courtyards, exposed beams, and roofs that swept outward like wings. Visitors described the experience as stepping into a structure that “breathed with the earth,” and the project established her reputation beyond her home city.

Aiko’s philosophy deepened through encounters with thinkers from the Cooperative Federation. She traveled widely in her thirties, studying Persian tilework gardens, Indian mandalas, and Chinese timber pavilions. Yet she always returned to wood as her central medium, arguing that it embodied the balance of permanence and impermanence: strong enough to endure, fragile enough to remind humanity of its own limits. Her essays from this period, later compiled in The Living Grain, remain touchstones for architects across Koina.

Her middle career was defined by civic commissions. Shrines, libraries, and town halls across East Asia bear her mark: carefully angled beams that guide the eye upward, latticed walls that scatter sunlight into geometric patterns, courtyards that framed not emptiness but presence. One of her most celebrated works, the Kyoto Resonant Library, became famous for its whispering acoustics — the walls themselves seemed to resonate with the sounds of turning pages and quiet voices.

Though deeply respected, Aiko’s career was not without conflict. She clashed repeatedly with industrialist patrons who sought monumental concrete projects, refusing commissions that compromised her principles. Her insistence on ecological integration — planting trees within courtyards, designing bridges that curved with rivers rather than spanning them rigidly — was sometimes dismissed as impractical or romantic. Yet these same choices later cemented her reputation as a pioneer of sustainable design, centuries before the concept became widespread.

Her studio became a space of both creativity and discipline. Apprentices recalled her intensity, demanding they master not only joinery but poetry, garden design, and calligraphy, for she believed architecture was the sum of all arts. She was known for rising before dawn to sketch in silence, often beginning her day by observing how light shifted through shoji screens. Despite her rigorous methods, her apprentices revered her, and many later became masters in their own right, spreading her vision across the federations.

In her personal life, Aiko was steady and private. She chose a few long-term partners across her life, all men, and was known for her loyalty and devotion. While her personal world was marked by serenity, her true love was her craft: colleagues often remarked that she gave more of herself to cedar beams and garden ponds than to any human relationship. This devotion did not diminish her warmth, but it meant that her legacy was written most clearly in wood and stone rather than domestic life.

Her later years were marked by refinement rather than reinvention. In the 1960s she designed a series of bridges in Nara and Osaka that embodied her lifelong philosophy of companionship. These structures seemed less like engineering feats and more like living beings, bending gracefully over rivers, harmonizing with mountainsides, and aging alongside the landscapes they inhabited. Even in her final years, weakened by illness, she walked construction sites to oversee her projects. It was on such an inspection in Nara in 1976 that she suffered a fatal stroke, passing away at the age of 72.

Legacy

Aiko’s ashes were interred beneath one of her cedar bridges, a final union of her life and her art. She is remembered not only as the Mother of Living Timber, but also as a philosopher who argued for architecture as companionship: the belief that buildings must breathe with their people and landscapes. Her works remain living testaments — not static monuments but places that continue to evolve with wind, light, and human presence.

Comments