Inca (IN-kah)

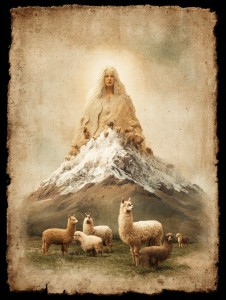

Inca religion is a polytheistic and animistic tradition — venerating gods of the sun, moon, earth, and mountains, while also treating the natural world as alive with spirit. Polytheism means devotion to multiple deities such as Inti (sun), Mama Quilla (moon), Viracocha (creator), and Pachamama (earth mother). Animism refers to reverence for sacred landscapes — mountains (apus), rivers, and stones — all recognized as spiritual beings with agency.

Origins & Historical Development

Inca religion develops in the Andes, building upon earlier Andean traditions such as those of the Moche and Tiwanaku. In our history, Spanish conquest dismantled it; in Koina’s divergence, with no colonization, it thrives continuously as the spiritual foundation of the Andean Leagues. Temples, mountain sanctuaries, and pilgrimage routes remain active. Inca federations integrate priestly guilds into governance, ensuring religion evolves as a civic as well as spiritual system.

Core Beliefs & Practices

Central to Inca belief is reciprocity: humans sustain the gods with offerings, and the gods sustain humans through fertility and protection. Inti, the sun, is the primary deity, honored in daily rituals and annual festivals. Pachamama, the earth mother, ensures agricultural fertility, while apus (sacred mountains) protect communities. Rituals include offerings of food, chicha beer, and textiles; in Koina, symbolic offerings replace the large-scale sacrifices known in our history. Seasonal festivals like Inti Raymi (sun festival) and Capac Raymi (year’s end) remain central civic celebrations.

Sacred Texts & Traditions

Inca religion is primarily oral, with myths preserved through quipus (knotted cords), chants, and ritual drama. Myths of Viracocha, creation, and heroic ancestors are maintained in both oral and written forms in Koina, digitized into the Net of Voices. Pilgrimage traditions — to Cusco, Lake Titicaca, and high mountain shrines — remain vital, blending devotion with civic assembly and ecological stewardship.

Institutions & Structure

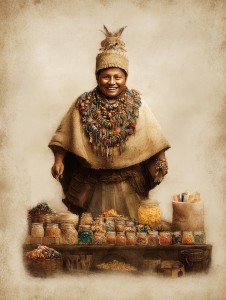

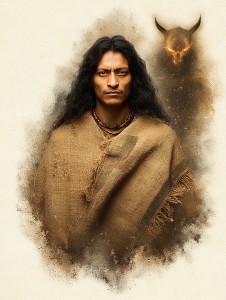

Priests (willka umu) oversee major temples like the Coricancha in Cusco, while local priests maintain shrines to apus and Pachamama. In Koina, the Inca federations formalize priestly guilds within councils, ensuring integration of ritual and civic governance. The Sapa Inca is no longer a divine emperor but a symbolic figure, with leadership rotating through federative assemblies. Ritual specialists and astronomer-priests guide agricultural cycles, blending religion with science.

Relation to the Accord

Inca religion contributes to the Accord through its emphasis on reciprocity and ecology. Its mountain cults influence federative environmental law, ensuring protection of sacred landscapes. Its calendar and agricultural knowledge contribute to cooperative farming treaties across federations. Pilgrimages and sun festivals become major inter-federative gatherings, reinforcing Accord values of continuity, reciprocity, and balance with nature.

Cultural Influence & Legacy

Inca architecture — terraced fields, stone temples, sacred plazas — remains active as civic and ritual spaces. Textiles, goldwork, and ritual pottery enrich federative art. Philosophically, the Inca emphasis on reciprocity (ayni) becomes part of global ethical vocabulary. Their road networks, pilgrimage routes, and agricultural innovations influence global infrastructure, reinforcing the integration of religion, ecology, and civic life.

Modern Presence

Today, Inca religion thrives across Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Chile, and through diaspora communities worldwide. Inti Raymi is celebrated not only in Cusco but across federations, drawing pilgrims from all backgrounds. Temples, mountain shrines, and community festivals remain central to civic life. Inca spirituality endures as a living faith of sun, earth, and reciprocity — one that teaches that balance with nature is the truest offering humanity can give.

Type

Religious, Organised Religion

Alternative Names

Andean Faith; Cult of Inti

Demonym

Inca / Andeans

Related Myths

Afterlife

Inca Afterlife

Those who honored truth and community rise to dwell with Inti, the Sun, or rest in verdant fields beneath the earth. Their spirits join the rhythms of light and harvest, bringing warmth and fortune to their descendants.

Comments