Celtic / Druidry (KEL-tik PAY-guh-nizm / DROO-id-ree)

Celtic Paganism is a polytheistic and animistic religion — meaning it venerates many deities while also recognizing spirits and sacred forces in rivers, groves, stones, and animals. Polytheism here refers to a pantheon of gods like Lugh, Brigid, and Cernunnos, each tied to natural and cultural domains. Animism means the natural world itself is alive and worthy of reverence. Together, these form a worldview where humans, gods, and nature are inseparably woven.

Origins & Historical Development

Celtic Paganism emerges across Iron Age Europe, practiced from Iberia to the Danube, from Gaul to the British Isles. In our history, Rome and Christianity suppressed it, leaving fragments. In Koina’s divergence, without Roman conquest or ecclesiastical persecution, Celtic religion never fades. Instead, it continues across the Celtic federations — Gaulish, Brythonic, Goidelic, Iberian-Celtic, and Galatian communities — adapting to changing times while retaining ritual and myth. Druidic orders evolve as federative guilds of philosophy, law, and ritual, linking Celtic regions into a loose but enduring cultural bloc.

Core Beliefs & Practices

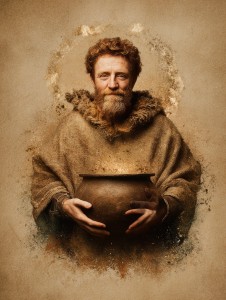

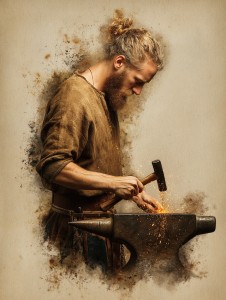

The Celtic worldview is relational: gods, humans, and nature exist in networks of reciprocity. The pantheon includes deities of sovereignty (Danu, Epona), craftsmanship (Goibniu, Brigid), war and protection (The Morrígan, Taranis), and seasonal cycles (Lugh, Cernunnos). Rituals often occur outdoors — in groves, at rivers, atop hills — with offerings of food, drink, or crafted goods. Festivals mark the turning of the year: Samhain (winter’s threshold), Imbolc (renewal), Beltane (fertility), and Lughnasadh (harvest). In Koina, these festivals become pan-federative gatherings, not suppressed remnants, celebrated in Celtic lands and shared abroad.

Sacred Texts & Traditions

Celtic religion is not scriptural but oral. Myths, genealogies, and poems are memorized and transmitted by druids, bards, and filí (poet-seers). In Koina, this oral corpus is never lost; it becomes recorded into the Net of Voices, preserving cycles such as the Ulster and Fenian tales, Gaulish hymns, and Iberian-Celtic myths. Philosophical dialogues by druids also enter federative archives, placing Celtic wisdom alongside Greek, Persian, and Indic texts.

Institutions & Structure

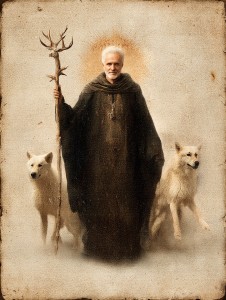

Druids serve as priests, judges, healers, and philosophers. Their authority is collegial, organized into councils across Celtic federations. Bards and seers form parallel orders, ensuring memory and prophecy remain central to civic life. In Koina, druidic orders integrate into the Accord’s system of Voices and Whispers, serving as mediators and guardians of law. Temples and sacred enclosures are built, but groves and rivers remain the holiest spaces, emphasizing continuity with nature.

Relation to the Accord

Celtic Paganism contributes to the Accord through its ecological ethos. Its reverence for natural forces influences federative treaties on forests, rivers, and sacred landscapes. Its festivals, rich in symbolism, spread across borders as shared celebrations of seasonal cycles. Druids often serve in councils as philosophers and mediators, their reputation for wisdom making them respected beyond Celtic lands.

Cultural Influence & Legacy

Celtic art — interlaced designs, spirals, animal motifs — becomes a signature style within Koina. Music, with harps, pipes, and communal singing, shapes wider federative traditions. Mythic cycles — of heroic quests, tragic lovers, or gods of sovereignty — inspire theater and literature across the Cooperative Federation. The idea of sovereignty as a sacred relationship between land, people, and ruler profoundly influences Accord political philosophy.

Modern Presence

Today, Celtic Paganism thrives across Ireland, Britain, Gaul, Iberia, and diaspora communities. Sacred groves and temples remain active; festivals like Beltane and Samhain are celebrated not only by Celts but across federations as cultural holidays of fire, harvest, and remembrance. Druidic orders are still recognized as guilds of philosophy and law, their teachings woven into ecological and legal frameworks of the Accord. Far from a vanished past, Celtic Paganism is a living religion of nature, community, and memory.

Type

Religious, Organised Religion

Alternative Names

The Old Ways; Path of the Druids

Demonym

Celts / Druids (for priestly class)

Related Myths

Afterlife

Celtic Afterlife

The Celts envisioned the Otherworld — Annwn or Tír na nÓg — as a radiant land beyond mist and sea. It is a place of eternal youth, song, and abundance where harmony with nature in life opens the path after death. Heroes, poets, and the wise are welcomed to its feasting halls, living in endless balance with the seasons.

Comments