Mexica / Aztec (MEH-shee-kah / AZ-tek)

Mexica religion is a polytheistic and cosmological tradition — venerating many gods tied to natural forces, war, fertility, and cosmic cycles. Polytheism means devotion to deities like Huitzilopochtli (sun and war), Tlaloc (rain), Quetzalcoatl (wisdom, wind), and Coatlicue (earth mother). It is also cosmological, meaning it interprets existence through cycles of creation and destruction — the “Five Suns” being successive worlds, each ending in cataclysm and renewal.

Origins & Historical Development

In our history, the Mexica Empire (Aztec) rose and fell under Spanish conquest. In Koina’s divergence, with no European colonization, Mexica religion develops continuously, evolving from city-state temples into federative councils of priests, astronomers, and philosophers. Without conquest, human sacrifice remains, but it shifts in meaning: smaller, symbolic offerings replace large-scale rites, integrated into festivals of renewal. Over time, the Mexica faith becomes one of the guiding spiritual forces of the Meso Leagues, shaping ecological and civic philosophy.

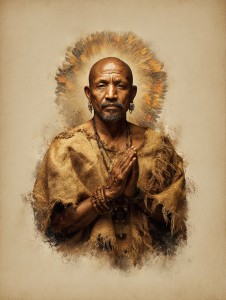

Core Beliefs & Practices

Mexica cosmology teaches that gods sacrificed themselves to create the world; humans must reciprocate through offerings to sustain cosmic balance. Rituals include bloodletting, food offerings, music, and dance. Gods embody dual aspects — benevolent and fearsome — reflecting the balance of life and death. Festivals mark agricultural cycles, solar events, and civic rites of renewal. In Koina, these festivals become federative celebrations where ritual drama, astronomy, and ecological stewardship intertwine.

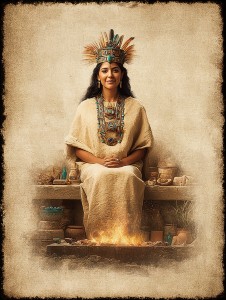

Sacred Texts & Traditions

Codices — pictorial manuscripts recording myths, genealogies, and rituals — preserve Mexica traditions. In Koina, these codices are never burned but digitized into the Net of Voices, ensuring preservation of mythic cycles. Oral traditions — songs, chants, and ritual speeches — remain central, performed at temples and festivals. The myth of the Five Suns and the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl becomes widely known across federations, inspiring global philosophical dialogue about cycles of time.

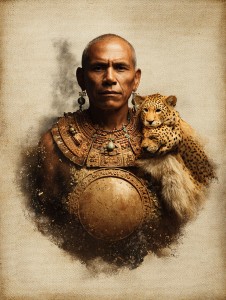

Institutions & Structure

Temples (teocalli) anchor each city, staffed by priests, astronomers, and ritual specialists. Priests oversee daily offerings and festivals, while astronomers track calendars and celestial events. In Koina, priestly guilds integrate into civic assemblies, ensuring ritual and governance remain intertwined. Education, particularly in astronomy and ritual philosophy, is a major civic duty, training generations in both science and religion.

Relation to the Accord

Mexica religion contributes to the Accord through its ecological and cosmic outlook. Its emphasis on reciprocity between gods and humans aligns with federative principles of reciprocity between communities. Its calendrical and astronomical expertise strengthens global science, feeding into cooperative observatories. Festivals of renewal — where cosmic cycles are ritually reenacted — become major cross-cultural events, reinforcing Accord values of continuity and balance.

Cultural Influence & Legacy

Mexica art — featherwork, sculpture, codices — flourishes, influencing global aesthetics. Architecture, with pyramid temples and ceremonial plazas, becomes part of Meso civic design. Philosophically, Mexica thought on cycles of destruction and renewal contributes to Koina’s plural cosmology, resonating with Indic and Norse ideas of cyclical time. Ethically, the emphasis on sacrifice and reciprocity informs federative law on duty, responsibility, and shared burden.

Modern Presence

Today, Mexica religion thrives in Mexico and across the Meso Leagues. Temples and festivals remain central to civic life, with rituals adapted to modern contexts. Pilgrimages to sacred sites like Tenochtitlan, Cholula, and Teotihuacan draw participants from across the Cooperative Federation. Mexica spirituality stands not as a defeated past but as a continuous, evolving tradition — one that affirms cosmic reciprocity and the shared responsibility of sustaining balance in the world.

Type

Religious, Organised Religion

Alternative Names

Mexica Faith; Nahua Religion

Demonym

Mexica / Nahua Peoples

Related Myths

Afterlife

Mexica Afterlife

The noble and the brave join Tonatiuh, the Sun, in his daily journey or rest within Tlalocan, the lush paradise of rain. Warriors rise with dawn’s light, and those of peaceful virtue dwell in verdant abundance beside the gods.

Comments