Taíno

Taíno religion is an animistic and polytheistic tradition — venerating many zemís (spirits and deities) tied to fertility, agriculture, weather, and ancestors. Animism means rivers, caves, and trees are alive with spirit. Polytheism refers to devotion to zemís such as Yúcahu (lord of cassava and agriculture), Atabey (goddess of waters and fertility), Guabancex (hurricane spirit), and countless local ancestral guardians.

Origins & Historical Development

The Taíno faith develops across the Caribbean islands, with roots in Arawakan traditions od the western continents. In our history, it was nearly eradicated by colonization. In Koina’s divergence, with no European conquest, the Taíno religion endures as the living spiritual framework of the Caribbean federations. Temples (bateyes), ballcourts, and caves remain active sacred sites, serving as both ritual and civic centers. By the modern era, the Taíno faith is recognized within the Accord as a vital maritime and island tradition, emphasizing harmony with sea and storm.

Core Beliefs & Practices

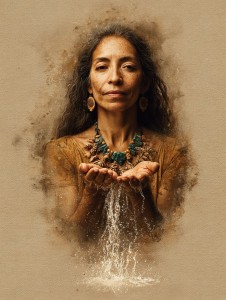

Taíno cosmology emphasizes reciprocity with zemís. Agriculture, fishing, and community life are sustained through offerings of cassava bread, tobacco, and areítos (ritual dances and songs). Shamans (bohiques) mediate between humans and spirits through trance, healing, and divination. Seasonal festivals mark planting, harvest, and the hurricane season, ensuring balance with natural cycles. In Koina, these festivals remain central to island federations and are often attended by visiting delegations from across the seas.

Sacred Texts & Traditions

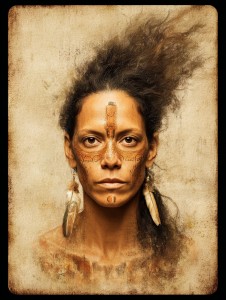

Taíno religion is oral, preserved through myths, chants, and ritual performance. Stories of creation, the descent into caves, and the deeds of zemís are passed down in ceremonial dances. In Koina, these are preserved in the Net of Voices but remain performed live in bateyes, where song and dance embody spiritual memory. Ritual ballgames also carry mythic significance, symbolizing cosmic struggle and renewal.

Institutions & Structure

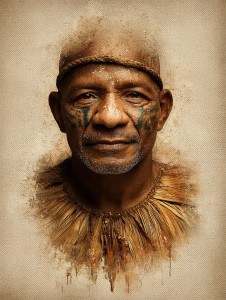

Authority rests with bohiques (shamans), who conduct healing, divination, and spirit mediation. Chiefs (caciques) hold both political and spiritual roles, responsible for maintaining harmony with zemís. In Koina, Taíno federations formally integrate bohiques into councils, ensuring that ecological and spiritual concerns guide governance. Sacred caves, rivers, and ballcourts remain focal points of both worship and assembly.

Relation to the Accord

The Taíno faith contributes to the Accord through its maritime and ecological worldview. Its reverence for the sea and storms informs federative treaties on navigation and disaster preparedness. Its rituals of reciprocity with zemís influence Accord ecological policies, treating natural forces as living partners. Festivals of areíto, with music, dance, and storytelling, become celebrated across the Cooperative Federation as symbols of joy, resilience, and renewal.

Cultural Influence & Legacy

Taíno art — zemí carvings, pottery, woven belts — enrich Koina’s material culture. Music and dance influence federative festivals, while ballgames become both sport and ritual across the western continents. Philosophically, the Taíno emphasis on reciprocity with natural forces adds to Koina’s plural ecology. Hurricanes, once feared as devastation, are ritually acknowledged as part of balance — a lesson that informs modern Accord disaster response.

Modern Presence

Today, Taíno religion thrives in the Caribbean, from Puerto Rico to Hispaniola to Cuba. Bateyes are active as temples, performance grounds, and civic centers. Areíto festivals attract pilgrims and tourists alike, celebrated as much for their philosophical meaning as for their beauty. Taíno spirituality endures as a living island tradition, teaching the Cooperative Federation that even storms and seas are kin, and that harmony with nature is the key to survival and joy.

Type

Religious, Organised Religion

Alternative Names

Zemi Faith; Way of the Taíno

Demonym

Taíno

Afterlife

Taino Afterlife

The good rest in Coabey, a gentle realm beneath the earth lit by ancestral fire. There, guided by Opiyel Guobiran, they dwell in serenity, their spirits intertwined with water and stone.

Comments