CTU: Cryptids-East Asia

Bulgae

Region: East Asia

Location:Korea (mythological celestial realms)

Bulgae are fiery, supernatural dogs from Korean mythology, originating in the realm of the underworld kingdom known as Gamangnara. According to legend, the king of this dark world desired the light of the sun and moon. He sent his hounds — massive, black or red-furred dogs with burning eyes and bodies made of embers — to chase and capture these celestial lights. When the Bulgae attempted to bite the sun, its heat scorched them, leaving their fur smoldering and their bodies aflame. Their attempts to seize the moon resulted in cool burn scars that gave them a ghostly glow.

Some legends use the Bulgae to explain eclipses. During a solar or lunar eclipse, people believed the Bulgae were attempting once again to take the celestial bodies, partially swallowing or covering them. The myth gave shape to the fear and awe surrounding sudden changes in the sky. The dogs’ failure — always burned or blinded by the brilliance of their prey — portrayed them as tragic figures, creatures of darkness yearning for light they could never hold.

Bulgae also appear symbolically in Korean art and folklore as embodiments of relentless pursuit. They are not evil beings but servants of a misguided master, driven to chase something impossible. Their burning bodies illuminate the night sky in stories, appearing as streaks of fire or glowing shapes. Though less common in modern storytelling than other yokai or spirits, the Bulgae remain a vivid mythic explanation for celestial events and the cycle of light and shadow.

Location:Korea (mythological celestial realms)

Bulgae are fiery, supernatural dogs from Korean mythology, originating in the realm of the underworld kingdom known as Gamangnara. According to legend, the king of this dark world desired the light of the sun and moon. He sent his hounds — massive, black or red-furred dogs with burning eyes and bodies made of embers — to chase and capture these celestial lights. When the Bulgae attempted to bite the sun, its heat scorched them, leaving their fur smoldering and their bodies aflame. Their attempts to seize the moon resulted in cool burn scars that gave them a ghostly glow.

Some legends use the Bulgae to explain eclipses. During a solar or lunar eclipse, people believed the Bulgae were attempting once again to take the celestial bodies, partially swallowing or covering them. The myth gave shape to the fear and awe surrounding sudden changes in the sky. The dogs’ failure — always burned or blinded by the brilliance of their prey — portrayed them as tragic figures, creatures of darkness yearning for light they could never hold.

Bulgae also appear symbolically in Korean art and folklore as embodiments of relentless pursuit. They are not evil beings but servants of a misguided master, driven to chase something impossible. Their burning bodies illuminate the night sky in stories, appearing as streaks of fire or glowing shapes. Though less common in modern storytelling than other yokai or spirits, the Bulgae remain a vivid mythic explanation for celestial events and the cycle of light and shadow.

Dokkaebi

Region: East Asia

Location:Korea (mountains, abandoned houses, crossroads)

Dokkaebi are Korean goblins known for their mischief, magical strength, and unpredictable sense of humor. They are not dead spirits but supernatural beings formed from inanimate objects imbued with spiritual energy — such as old brooms, clay jars, or tools left unused for too long. They appear with distinctive features: horn-like lumps on their heads, wide grins, and colorful robes. Some carry magical clubs (*dokkaebi bangmangi*) that can summon wealth, food, or objects — though usually with chaotic results.

Their behavior blends generosity with trickery. Dokkaebi enjoy challenging humans to wrestling matches, strength contests, riddles, or drinking games. Those who behave honorably or entertain the dokkaebi may be rewarded with treasure or protection. But people who are greedy, lazy, or deceitful are humiliated — sometimes by illusions, sometimes through physical pranks, sometimes by being abandoned naked on a distant mountain. Their sense of justice is skewed but consistent: they reward wit and punish arrogance.

Though often comical, Dokkaebi also embody nature’s unpredictability. They wander forests, appear at lonely roads at dusk, and gather at abandoned structures. Their stories teach lessons about humility and cleverness while celebrating humor as a survival tool. In Korean culture, Dokkaebi remain beloved figures who represent chaos, generosity, and the thrill of encountering something extraordinary in an otherwise ordinary world.

Location:Korea (mountains, abandoned houses, crossroads)

Dokkaebi are Korean goblins known for their mischief, magical strength, and unpredictable sense of humor. They are not dead spirits but supernatural beings formed from inanimate objects imbued with spiritual energy — such as old brooms, clay jars, or tools left unused for too long. They appear with distinctive features: horn-like lumps on their heads, wide grins, and colorful robes. Some carry magical clubs (*dokkaebi bangmangi*) that can summon wealth, food, or objects — though usually with chaotic results.

Their behavior blends generosity with trickery. Dokkaebi enjoy challenging humans to wrestling matches, strength contests, riddles, or drinking games. Those who behave honorably or entertain the dokkaebi may be rewarded with treasure or protection. But people who are greedy, lazy, or deceitful are humiliated — sometimes by illusions, sometimes through physical pranks, sometimes by being abandoned naked on a distant mountain. Their sense of justice is skewed but consistent: they reward wit and punish arrogance.

Though often comical, Dokkaebi also embody nature’s unpredictability. They wander forests, appear at lonely roads at dusk, and gather at abandoned structures. Their stories teach lessons about humility and cleverness while celebrating humor as a survival tool. In Korean culture, Dokkaebi remain beloved figures who represent chaos, generosity, and the thrill of encountering something extraordinary in an otherwise ordinary world.

Huli Jing

Region: East Asia

Location:China (widespread in literature, myth, and local folklore)

Huli Jing — the Chinese fox spirit — shares similarities with Japan’s kitsune but has its own distinct cultural lineage. Huli Jing are portrayed as shape-shifting foxes that cultivate magical power over centuries. When they reach fifty years, they may take on human form; after a hundred years, they can become fully human-like, often appearing as beautiful women or enigmatic scholars. Their transformations are driven by spiritual cultivation rather than innate ability, and they may require moonlight, meditation, or special rituals to maintain their human guise.

In Chinese literature, Huli Jing occupy a wide moral spectrum. Some stories romanticize them as loyal lovers who protect humans or bring prosperity. Others portray them as seductresses who drain men’s life force or manipulate households from within. The *Shan Hai Jing* and later Ming and Qing dynasty texts describe them as wise, clever, and emotionally complex — neither purely benevolent nor malevolent. Their nine-tailed form, the ultimate stage of their evolution, is associated with divine or cosmic significance.

Huli Jing stories often explore themes of illusion, desire, and the blurred boundary between the mundane and the supernatural. They ask whether a being who appears human but isn’t can still form genuine bonds — and whether humans can see past their fears. Even now, Huli Jing appear in modern film, literature, and art as symbols of transformation and the power of charm, wit, and mystery.

Location:China (widespread in literature, myth, and local folklore)

Huli Jing — the Chinese fox spirit — shares similarities with Japan’s kitsune but has its own distinct cultural lineage. Huli Jing are portrayed as shape-shifting foxes that cultivate magical power over centuries. When they reach fifty years, they may take on human form; after a hundred years, they can become fully human-like, often appearing as beautiful women or enigmatic scholars. Their transformations are driven by spiritual cultivation rather than innate ability, and they may require moonlight, meditation, or special rituals to maintain their human guise.

In Chinese literature, Huli Jing occupy a wide moral spectrum. Some stories romanticize them as loyal lovers who protect humans or bring prosperity. Others portray them as seductresses who drain men’s life force or manipulate households from within. The *Shan Hai Jing* and later Ming and Qing dynasty texts describe them as wise, clever, and emotionally complex — neither purely benevolent nor malevolent. Their nine-tailed form, the ultimate stage of their evolution, is associated with divine or cosmic significance.

Huli Jing stories often explore themes of illusion, desire, and the blurred boundary between the mundane and the supernatural. They ask whether a being who appears human but isn’t can still form genuine bonds — and whether humans can see past their fears. Even now, Huli Jing appear in modern film, literature, and art as symbols of transformation and the power of charm, wit, and mystery.

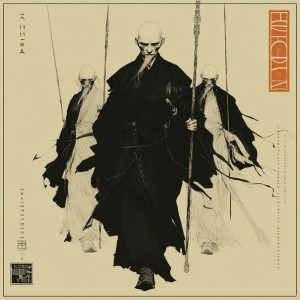

Jeoseung Saja

Region: East Asia

Location:Korea (mythology, funeral lore)

Jeoseung Saja — the reapers or death messengers of Korean folklore — are beings who escort souls to the afterlife. They are not malevolent but inevitable, performing their duty with quiet dignity. Typically depicted as tall figures wearing black hats and simple white or black robes, they carry a staff or ledger listing the names of the dying. When a Jeoseung Saja appears, it signifies that a person’s time has come. They do not harm or frighten; they simply guide, ensuring the soul does not wander or linger.

Stories emphasize their impartial nature. Unlike demons or restless spirits, Jeoseung Saja cannot be bribed, delayed, or deceived. Even the most virtuous families or the most powerful officials cannot resist their arrival. Some tales portray the Saja as unexpectedly compassionate — comforting the grieving, protecting the dying from malevolent spirits, or gently encouraging reluctant souls. Other stories describe rare moments where a Saja grants a reprieve due to clerical errors in the ledger, though these are exceptions, often ending with the debt repaid later.

In Korean culture, Jeoseung Saja reflect a view of death as a natural transition rather than a battle. Their presence is solemn but not terrifying, embodying order and inevitability. They reinforce cultural values surrounding respect for ancestors, preparation for the end of life, and the belief that the world of the living and the dead are parallel realms connected through ritual and duty. Even in modern media, Saja remain iconic — quiet guardians of the threshold between worlds.

Location:Korea (mythology, funeral lore)

Jeoseung Saja — the reapers or death messengers of Korean folklore — are beings who escort souls to the afterlife. They are not malevolent but inevitable, performing their duty with quiet dignity. Typically depicted as tall figures wearing black hats and simple white or black robes, they carry a staff or ledger listing the names of the dying. When a Jeoseung Saja appears, it signifies that a person’s time has come. They do not harm or frighten; they simply guide, ensuring the soul does not wander or linger.

Stories emphasize their impartial nature. Unlike demons or restless spirits, Jeoseung Saja cannot be bribed, delayed, or deceived. Even the most virtuous families or the most powerful officials cannot resist their arrival. Some tales portray the Saja as unexpectedly compassionate — comforting the grieving, protecting the dying from malevolent spirits, or gently encouraging reluctant souls. Other stories describe rare moments where a Saja grants a reprieve due to clerical errors in the ledger, though these are exceptions, often ending with the debt repaid later.

In Korean culture, Jeoseung Saja reflect a view of death as a natural transition rather than a battle. Their presence is solemn but not terrifying, embodying order and inevitability. They reinforce cultural values surrounding respect for ancestors, preparation for the end of life, and the belief that the world of the living and the dead are parallel realms connected through ritual and duty. Even in modern media, Saja remain iconic — quiet guardians of the threshold between worlds.

Jiangshi

Region: East Asia

Location:China (widespread across northern and southern folklore)

The Jiangshi is one of the most recognizable beings in Chinese folklore — a reanimated corpse that moves by hopping with stiff, outstretched arms. Its rigidity comes from the belief that corpses stiffen after death, so when they rise they cannot bend their limbs. Jiangshi wear Qing Dynasty mandarin robes, with pale or greenish skin, long black hair, and sometimes a paper talisman stuck to their foreheads to restrain them. They sense life not by sight but by the breath or qi of living beings.

Folklore offers multiple origins for a Jiangshi: improper burial, violent death, unfulfilled purpose, or the corruption of qi. Some are created through sorcery or Taoist rituals gone wrong. Jiangshi feed on the living — either consuming blood, qi, or life energy depending on the region. To evade them, people carry charms like mirrors, peachwood talismans, or rooster crow sounds, which are believed to repel undead spirits. Taoist priests in traditional stories engage Jiangshi using chanting, bells, and ritual magic.

Beyond horror, Jiangshi reflect deep cultural anxieties surrounding improper burials, liminality of death, and unsettled spirits. Migrant workers who died far from home were sometimes transported in upright posture, bound between bamboo poles — a practice later romanticized into stories of “corpses walking home.” Over centuries, Jiangshi evolved from chilling figures in ghost tales to iconic symbols in opera, film, and literature. They remain one of China’s most enduring supernatural archetypes.

Location:China (widespread across northern and southern folklore)

The Jiangshi is one of the most recognizable beings in Chinese folklore — a reanimated corpse that moves by hopping with stiff, outstretched arms. Its rigidity comes from the belief that corpses stiffen after death, so when they rise they cannot bend their limbs. Jiangshi wear Qing Dynasty mandarin robes, with pale or greenish skin, long black hair, and sometimes a paper talisman stuck to their foreheads to restrain them. They sense life not by sight but by the breath or qi of living beings.

Folklore offers multiple origins for a Jiangshi: improper burial, violent death, unfulfilled purpose, or the corruption of qi. Some are created through sorcery or Taoist rituals gone wrong. Jiangshi feed on the living — either consuming blood, qi, or life energy depending on the region. To evade them, people carry charms like mirrors, peachwood talismans, or rooster crow sounds, which are believed to repel undead spirits. Taoist priests in traditional stories engage Jiangshi using chanting, bells, and ritual magic.

Beyond horror, Jiangshi reflect deep cultural anxieties surrounding improper burials, liminality of death, and unsettled spirits. Migrant workers who died far from home were sometimes transported in upright posture, bound between bamboo poles — a practice later romanticized into stories of “corpses walking home.” Over centuries, Jiangshi evolved from chilling figures in ghost tales to iconic symbols in opera, film, and literature. They remain one of China’s most enduring supernatural archetypes.

Jorōgumo

Region: East Asia

Location:Japan (mountain passes, abandoned houses, waterfalls)

Jorōgumo is a shape-shifting yokai described as a giant spider that can transform into a beautiful woman. In her human guise, she is alluring and elegant, often appearing near remote paths, waterfalls, or old inns where travelers pass through alone. Traditional stories from Edo-period kaidan collections describe her inviting men into abandoned houses or dense forests, offering hospitality or seduction before trapping them in webs. Once her victim is immobilized, she reveals her spider form and devours them at leisure.

Some versions of the legend connect Jorōgumo to specific locations — most famously the Jōren Falls in Shizuoka Prefecture, where she is said to lure men with haunting flute music. The spider form is enormous, with legs stretching as long as tree branches and webs strong enough to restrain even the strongest warriors. In other tales, Jorōgumo controls swarms of lesser spiders, commanding them to weaken or poison victims. Her silk is often described as shimmering like silver thread, deceptively delicate yet impossibly strong.

While many yokai have benevolent or humorous aspects, Jorōgumo remains firmly predatory in most stories. She represents the danger of illusions, particularly the allure that conceals harm. Travelers were cautioned to avoid beautiful women appearing alone in desolate places and to distrust sudden hospitality from strangers. As a folkloric figure, the Jorōgumo stands as a powerful symbol of seduction blended with lethal intent — a reminder that beauty and danger often dwell in the same shadow.

Location:Japan (mountain passes, abandoned houses, waterfalls)

Jorōgumo is a shape-shifting yokai described as a giant spider that can transform into a beautiful woman. In her human guise, she is alluring and elegant, often appearing near remote paths, waterfalls, or old inns where travelers pass through alone. Traditional stories from Edo-period kaidan collections describe her inviting men into abandoned houses or dense forests, offering hospitality or seduction before trapping them in webs. Once her victim is immobilized, she reveals her spider form and devours them at leisure.

Some versions of the legend connect Jorōgumo to specific locations — most famously the Jōren Falls in Shizuoka Prefecture, where she is said to lure men with haunting flute music. The spider form is enormous, with legs stretching as long as tree branches and webs strong enough to restrain even the strongest warriors. In other tales, Jorōgumo controls swarms of lesser spiders, commanding them to weaken or poison victims. Her silk is often described as shimmering like silver thread, deceptively delicate yet impossibly strong.

While many yokai have benevolent or humorous aspects, Jorōgumo remains firmly predatory in most stories. She represents the danger of illusions, particularly the allure that conceals harm. Travelers were cautioned to avoid beautiful women appearing alone in desolate places and to distrust sudden hospitality from strangers. As a folkloric figure, the Jorōgumo stands as a powerful symbol of seduction blended with lethal intent — a reminder that beauty and danger often dwell in the same shadow.

Kappa

Region: East Asia

Location:Japan (rivers, ponds, irrigation canals)

Kappa are among Japan’s most distinct yokai — water-dwelling creatures described as child-sized, humanlike beings with scaly or slimy green skin, webbed hands and feet, and a turtle-like shell on their back. Their most iconic feature is the *sara* — a shallow dish-like depression on the top of their head that holds water. This water is the source of the Kappa’s strength, intelligence, and life-force. If the *sara* spills or dries out, the Kappa becomes weakened or immobilized. Folklore presents them as simultaneously mischievous and dangerous: pranksters with a dark streak who interact unpredictably with humans.

Traditional stories paint Kappa as both threats and teachers. They are known for dragging animals — and sometimes humans — into rivers, pulling victims underwater with surprising strength. But they are also bound by etiquette. Kappa are compelled to bow when bowed to; doing so spills the water from their heads, rendering them powerless and allowing humans to escape or negotiate. Farmers often made pacts with local Kappa for safe waterways or protection from drowning, leaving offerings of cucumbers (the Kappa’s favorite food) carved with their names.

Over time, the Kappa became symbolic cautionary figures, warning children about river dangers and the unpredictability of nature. Edo-period writings depict them as powerful swimmers who compete with humans or challenge travelers to sumo wrestling. Modern portrayals softened them into more comical beings, but the older stories remain vivid: creatures of the water, ruled by politeness, and capable of both kindness and harm depending on how they are treated.

Location:Japan (rivers, ponds, irrigation canals)

Kappa are among Japan’s most distinct yokai — water-dwelling creatures described as child-sized, humanlike beings with scaly or slimy green skin, webbed hands and feet, and a turtle-like shell on their back. Their most iconic feature is the *sara* — a shallow dish-like depression on the top of their head that holds water. This water is the source of the Kappa’s strength, intelligence, and life-force. If the *sara* spills or dries out, the Kappa becomes weakened or immobilized. Folklore presents them as simultaneously mischievous and dangerous: pranksters with a dark streak who interact unpredictably with humans.

Traditional stories paint Kappa as both threats and teachers. They are known for dragging animals — and sometimes humans — into rivers, pulling victims underwater with surprising strength. But they are also bound by etiquette. Kappa are compelled to bow when bowed to; doing so spills the water from their heads, rendering them powerless and allowing humans to escape or negotiate. Farmers often made pacts with local Kappa for safe waterways or protection from drowning, leaving offerings of cucumbers (the Kappa’s favorite food) carved with their names.

Over time, the Kappa became symbolic cautionary figures, warning children about river dangers and the unpredictability of nature. Edo-period writings depict them as powerful swimmers who compete with humans or challenge travelers to sumo wrestling. Modern portrayals softened them into more comical beings, but the older stories remain vivid: creatures of the water, ruled by politeness, and capable of both kindness and harm depending on how they are treated.

Kitsune

Region: East Asia

Location:Japan (nationwide; associated with shrines, forests, villages)

Kitsune are fox spirits known for intelligence, magical ability, and shapeshifting. In Japanese folklore, foxes live long lives, and as they grow older, they gain supernatural powers — most famously the ability to take human form. Kitsune often appear as beautiful women, wandering monks, or elderly men. Their true form may be revealed by a shadow that betrays a fox tail, a reflection that differs from their disguise, or their inability to hide their sharp voices. They may possess multiple tails — the oldest and most powerful having up to nine, each tail marking a century of power.

The dual nature of Kitsune is key to understanding their lore. *Zenko* (good foxes) are associated with Inari, the Shinto deity of rice and prosperity; these kitsune act as messengers or guardians, offering blessings, protection, and guidance. *Yako* (wild foxes), on the other hand, are tricksters — mischievous beings who possess people, deceive them, or play elaborate pranks. Some stories depict kitsune seducing humans, forming marriages that last years before the truth is revealed. Others portray foxes rewarding kind farmers or humiliating greedy officials.

Kitsune appear across Japan’s literary and oral traditions as beings who blur boundaries — between human and animal, wisdom and foolishness, danger and grace. Their image shifts from mischievous prankster to divine envoy, but their core remains the same: they are creatures of cunning, illusion, and transformation. Whether feared, respected, or adored, kitsune embody the unpredictable magic running through Japan’s forests and fields.

Location:Japan (nationwide; associated with shrines, forests, villages)

Kitsune are fox spirits known for intelligence, magical ability, and shapeshifting. In Japanese folklore, foxes live long lives, and as they grow older, they gain supernatural powers — most famously the ability to take human form. Kitsune often appear as beautiful women, wandering monks, or elderly men. Their true form may be revealed by a shadow that betrays a fox tail, a reflection that differs from their disguise, or their inability to hide their sharp voices. They may possess multiple tails — the oldest and most powerful having up to nine, each tail marking a century of power.

The dual nature of Kitsune is key to understanding their lore. *Zenko* (good foxes) are associated with Inari, the Shinto deity of rice and prosperity; these kitsune act as messengers or guardians, offering blessings, protection, and guidance. *Yako* (wild foxes), on the other hand, are tricksters — mischievous beings who possess people, deceive them, or play elaborate pranks. Some stories depict kitsune seducing humans, forming marriages that last years before the truth is revealed. Others portray foxes rewarding kind farmers or humiliating greedy officials.

Kitsune appear across Japan’s literary and oral traditions as beings who blur boundaries — between human and animal, wisdom and foolishness, danger and grace. Their image shifts from mischievous prankster to divine envoy, but their core remains the same: they are creatures of cunning, illusion, and transformation. Whether feared, respected, or adored, kitsune embody the unpredictable magic running through Japan’s forests and fields.

Mogwai

Region: East Asia

Location:China (southern provinces, Cantonese folklore)

Before Hollywood turned “mogwai” into a cute troublemaker, the Cantonese term *mo gwai* simply meant “monster,” “demon,” or “malicious spirit.” In traditional folklore, mogwai are beings formed from negative qi — the accumulated resentment, fear, or suffering of humans. Some are born from the restless energy of the recently dead; others emerge from places associated with tragedy or neglect. Mogwai are unpredictable, appearing in many shapes: shadows with eyes, twisted animal figures, or ghostlike forms that distort as they move.

Folklore describes mogwai as opportunistic: they target individuals who are weakened emotionally, grieving, or morally compromised. Their influence can manifest through nightmares, misfortune, or uncanny disturbances in the home. Unlike ghosts, mogwai are not tied to human spirits but arise from environmental imbalance. Taoist priests traditionally address mogwai by restoring harmony, not by exorcism alone. Rituals may involve balancing yin and yang, using incense or music, or clearing stagnant qi from living spaces.

Mogwai also serve as moral warnings. Stories caution against greed, anger, or cruelty — emotions that can “birth” mogwai in households or villages. Their presence reflects the idea that internal turmoil can manifest externally. In modern times, the term is still used jokingly to refer to mischievous children or pets, but its original meaning remains rooted in the concept of unseen forces shaped by human behavior and environmental disharmony.

Location:China (southern provinces, Cantonese folklore)

Before Hollywood turned “mogwai” into a cute troublemaker, the Cantonese term *mo gwai* simply meant “monster,” “demon,” or “malicious spirit.” In traditional folklore, mogwai are beings formed from negative qi — the accumulated resentment, fear, or suffering of humans. Some are born from the restless energy of the recently dead; others emerge from places associated with tragedy or neglect. Mogwai are unpredictable, appearing in many shapes: shadows with eyes, twisted animal figures, or ghostlike forms that distort as they move.

Folklore describes mogwai as opportunistic: they target individuals who are weakened emotionally, grieving, or morally compromised. Their influence can manifest through nightmares, misfortune, or uncanny disturbances in the home. Unlike ghosts, mogwai are not tied to human spirits but arise from environmental imbalance. Taoist priests traditionally address mogwai by restoring harmony, not by exorcism alone. Rituals may involve balancing yin and yang, using incense or music, or clearing stagnant qi from living spaces.

Mogwai also serve as moral warnings. Stories caution against greed, anger, or cruelty — emotions that can “birth” mogwai in households or villages. Their presence reflects the idea that internal turmoil can manifest externally. In modern times, the term is still used jokingly to refer to mischievous children or pets, but its original meaning remains rooted in the concept of unseen forces shaped by human behavior and environmental disharmony.

Comments