CTU: Cryptids-Central & Southeastern Europe

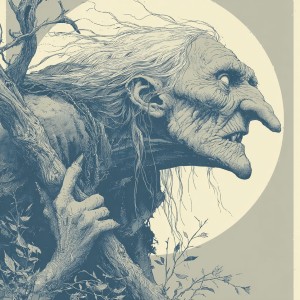

Baba Yaga

Region: Central & Southeastern Europe

Location:Slavic regions — Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Poland

Baba Yaga is one of the most complex and enduring beings in Slavic folklore — a witch-spirit who lives deep in the forest in a hut that stands on chicken legs. She is described as a skeletal old woman with iron teeth, long hair, and a nose sharp enough to “touch the ceiling.” Baba Yaga flies through the air in a mortar, steering with a pestle, and sweeping away her tracks with a broom made of silver birch. Her home rotates or moves aside to allow entry when she gives permission; the fence surrounding it is often said to be built from bones topped with glowing skulls.

Her nature is ambiguous: she can be monstrous, devouring travelers or coercing them into impossible tasks, yet she is also a guardian of knowledge and an initiator of heroes. Those who approach respectfully — offering food, answering riddles, or keeping their wits — may gain magical items, prophetic advice, or protection. In many tales, she represents the boundary between the civilized world and the raw wilderness. The forest she inhabits symbolizes transformation: entering it is a test, and leaving it changed is the reward or punishment.

Baba Yaga’s endurance comes from her role as a figure of deep mythic archetype — part goddess, part demon, part wise-woman, part storm spirit. She is the keeper of thresholds: between life and death, childhood and adulthood, safety and danger. Unlike simplistic villains, Baba Yaga resists categorization. She forces characters to confront fear, cunning, humility, and survival. Her image remains one of Eastern Europe’s most iconic embodiments of the wild feminine and the unforgiving, mystical forest.

Location:Slavic regions — Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Poland

Baba Yaga is one of the most complex and enduring beings in Slavic folklore — a witch-spirit who lives deep in the forest in a hut that stands on chicken legs. She is described as a skeletal old woman with iron teeth, long hair, and a nose sharp enough to “touch the ceiling.” Baba Yaga flies through the air in a mortar, steering with a pestle, and sweeping away her tracks with a broom made of silver birch. Her home rotates or moves aside to allow entry when she gives permission; the fence surrounding it is often said to be built from bones topped with glowing skulls.

Her nature is ambiguous: she can be monstrous, devouring travelers or coercing them into impossible tasks, yet she is also a guardian of knowledge and an initiator of heroes. Those who approach respectfully — offering food, answering riddles, or keeping their wits — may gain magical items, prophetic advice, or protection. In many tales, she represents the boundary between the civilized world and the raw wilderness. The forest she inhabits symbolizes transformation: entering it is a test, and leaving it changed is the reward or punishment.

Baba Yaga’s endurance comes from her role as a figure of deep mythic archetype — part goddess, part demon, part wise-woman, part storm spirit. She is the keeper of thresholds: between life and death, childhood and adulthood, safety and danger. Unlike simplistic villains, Baba Yaga resists categorization. She forces characters to confront fear, cunning, humility, and survival. Her image remains one of Eastern Europe’s most iconic embodiments of the wild feminine and the unforgiving, mystical forest.

Basilisk

Region: Central & Southeastern Europe

Location:German-speaking regions and Switzerland; medieval Europe broadly

The German/Swiss Basilisk differs significantly from the classical Mediterranean version. In Central Europe, the Basilisk is described as a hybrid between a serpent and a rooster — often with the head and comb of a cockerel, the body of a snake or lizard, and sometimes a crown-like crest. It is said to be born from a rooster’s egg — a malformed or magical egg — incubated by a serpent or toad. The Basilisk’s defining power is its lethal gaze or breath: it can kill with a glance, wilt plants, crack stones, and poison water sources.

Many medieval towns had Basilisk legends tied to specific wells, sewers, or abandoned buildings. In the Swiss city of Basel — whose very name echoes “Basilisk” in later retellings — stories told of a creature lurking in a well beneath the old city. People avoided the area for fear of sudden death from sight or vapor. In German towns, the Basilisk symbolized contamination, plague, or dangerous, unseen poisons in urban environments. As urbanization spread, these beings came to represent fears of disease, sewage, and animals living in dark places.

The Basilisk could be defeated through cunning, not violence. Mirrors were used to force it to kill itself with its own gaze, or roosters were introduced to challenge its identity. These stories blend Christian symbolism, practical city fears, and ancient mythic elements. The Basilisk remains one of the most recognizable creatures of medieval Germanic folklore — a reminder of how people conceptualized invisible danger long before modern science.

Location:German-speaking regions and Switzerland; medieval Europe broadly

The German/Swiss Basilisk differs significantly from the classical Mediterranean version. In Central Europe, the Basilisk is described as a hybrid between a serpent and a rooster — often with the head and comb of a cockerel, the body of a snake or lizard, and sometimes a crown-like crest. It is said to be born from a rooster’s egg — a malformed or magical egg — incubated by a serpent or toad. The Basilisk’s defining power is its lethal gaze or breath: it can kill with a glance, wilt plants, crack stones, and poison water sources.

Many medieval towns had Basilisk legends tied to specific wells, sewers, or abandoned buildings. In the Swiss city of Basel — whose very name echoes “Basilisk” in later retellings — stories told of a creature lurking in a well beneath the old city. People avoided the area for fear of sudden death from sight or vapor. In German towns, the Basilisk symbolized contamination, plague, or dangerous, unseen poisons in urban environments. As urbanization spread, these beings came to represent fears of disease, sewage, and animals living in dark places.

The Basilisk could be defeated through cunning, not violence. Mirrors were used to force it to kill itself with its own gaze, or roosters were introduced to challenge its identity. These stories blend Christian symbolism, practical city fears, and ancient mythic elements. The Basilisk remains one of the most recognizable creatures of medieval Germanic folklore — a reminder of how people conceptualized invisible danger long before modern science.

Krampus

Region: Central & Southeastern Europe

Location:Alpine regions — Austria, Bavaria, Tyrol, Slovenia

Krampus is a horned, goat-footed spirit who appears during midwinter, specifically on the night of December 5th (Krampusnacht), accompanying Saint Nicholas in Alpine folklore. He is depicted as a towering figure with shaggy black or brown fur, cloven hooves, curling horns, and a long tongue that lolls from his mouth. He carries chains, which he rattles as a symbol of binding demonic forces, and he often wields a bundle of birch rods used for swatting misbehaving children. In some versions, Krampus also carries a wicker basket or sack on his back to cart away those who behave wickedly.

Krampus is the embodiment of the dark half of winter morality — a necessary counterpart to the benevolent gift-giver. Historically, Alpine communities understood winter as a season of danger: famine, cold, and scarcity. Figures like Krampus served as warnings and social regulators, reminding children to obey community norms and discouraging behavior that could threaten group survival. Krampus is not simply a monster; he is part of a moral duality rooted in Europe’s pre-Christian traditions of winter solstice spirits, later assimilated into Christianized customs.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Krampus was celebrated in village parades, where costumed men wearing carved wooden masks and bells charged through the streets, frightening spectators with controlled chaos. These events combined fear, humor, and catharsis, allowing communities to confront the darker aspects of the season through ritual. Today, Krampus has become a global icon, but in the Alpine homeland he remains tied to local identity — a creature of cold nights, clattering bells, and ancient rituals carved into mountain memory.

Location:Alpine regions — Austria, Bavaria, Tyrol, Slovenia

Krampus is a horned, goat-footed spirit who appears during midwinter, specifically on the night of December 5th (Krampusnacht), accompanying Saint Nicholas in Alpine folklore. He is depicted as a towering figure with shaggy black or brown fur, cloven hooves, curling horns, and a long tongue that lolls from his mouth. He carries chains, which he rattles as a symbol of binding demonic forces, and he often wields a bundle of birch rods used for swatting misbehaving children. In some versions, Krampus also carries a wicker basket or sack on his back to cart away those who behave wickedly.

Krampus is the embodiment of the dark half of winter morality — a necessary counterpart to the benevolent gift-giver. Historically, Alpine communities understood winter as a season of danger: famine, cold, and scarcity. Figures like Krampus served as warnings and social regulators, reminding children to obey community norms and discouraging behavior that could threaten group survival. Krampus is not simply a monster; he is part of a moral duality rooted in Europe’s pre-Christian traditions of winter solstice spirits, later assimilated into Christianized customs.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Krampus was celebrated in village parades, where costumed men wearing carved wooden masks and bells charged through the streets, frightening spectators with controlled chaos. These events combined fear, humor, and catharsis, allowing communities to confront the darker aspects of the season through ritual. Today, Krampus has become a global icon, but in the Alpine homeland he remains tied to local identity — a creature of cold nights, clattering bells, and ancient rituals carved into mountain memory.

Leshy

Region: Central & Southeastern Europe

Location:Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, and broader Slavic forests

The Leshy is a forest guardian spirit in Slavic folklore — a shapeshifting being who protects wild animals, trees, and sacred forest places. He typically appears as a tall man with pale skin, long hair, and a beard made of grass, vines, or moss. In many tales, his height shifts with the trees: towering among pines but shrinking to the size of a blade of grass when crossing a field. His eyes shine like leaves in sunlight or glow like moonlit stones. Sometimes he appears with backward-facing hands or mismatched features, signaling his otherworldly nature.

The Leshy is not inherently good or evil. He can be a protector or a trickster depending on how humans behave in his forest. Travelers who respect the woods — offering bread, salt, or simply speaking kindly — may find the Leshy guiding them out of danger, calming wolves, or protecting them from storms. But those who cut sacred trees, hunt excessively, or disrespect animals may be punished. Common punishments include leading them in circles until they are lost, stealing voices, or mimicking familiar sounds to lure them deeper into the forest. His laughter is said to carry unnaturally far, like the rustling of leaves mixed with echo.

The Leshy embodies the Slavic worldview that forests are living, sentient spaces with their own guardians. He represents ecological balance long before the term existed. Many villages believed treaties could be made with the Leshy, ensuring safe passage in exchange for restraint. His stories are reminders of the dangers of the wild, the power of nature, and the need for respect when entering places older than human settlement.

Location:Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, and broader Slavic forests

The Leshy is a forest guardian spirit in Slavic folklore — a shapeshifting being who protects wild animals, trees, and sacred forest places. He typically appears as a tall man with pale skin, long hair, and a beard made of grass, vines, or moss. In many tales, his height shifts with the trees: towering among pines but shrinking to the size of a blade of grass when crossing a field. His eyes shine like leaves in sunlight or glow like moonlit stones. Sometimes he appears with backward-facing hands or mismatched features, signaling his otherworldly nature.

The Leshy is not inherently good or evil. He can be a protector or a trickster depending on how humans behave in his forest. Travelers who respect the woods — offering bread, salt, or simply speaking kindly — may find the Leshy guiding them out of danger, calming wolves, or protecting them from storms. But those who cut sacred trees, hunt excessively, or disrespect animals may be punished. Common punishments include leading them in circles until they are lost, stealing voices, or mimicking familiar sounds to lure them deeper into the forest. His laughter is said to carry unnaturally far, like the rustling of leaves mixed with echo.

The Leshy embodies the Slavic worldview that forests are living, sentient spaces with their own guardians. He represents ecological balance long before the term existed. Many villages believed treaties could be made with the Leshy, ensuring safe passage in exchange for restraint. His stories are reminders of the dangers of the wild, the power of nature, and the need for respect when entering places older than human settlement.

Moroi

Region: Central & Southeastern Europe

Location:Romania (especially rural southern regions)

Moroi are often paired with strigoi in Romanian belief, but they are distinct. Where the strigoi are undead revenants, **moroi are living beings** — people afflicted by a spiritual condition that drains vitality from others, often unknowingly. A moroi may be a child born with unusual features, a person touched by a curse, or someone who becomes parasitic through misfortune or trauma. In some regions, moroi are said to leave their bodies at night, wandering as ghostlike doubles that feed on the energy of livestock, neighbors, or relatives.

Descriptions vary: some moroi remain physically normal, while others become frail, hollow-eyed, or marked by strange birth signs. Their draining presence manifests in community misfortunes — milk curdling, animals growing weak, children becoming sickly, crops failing. Because the condition can affect infants, families were especially vigilant, placing amulets, garlic, or iron tools near cradles. The boundary between moroi and witch is fluid; some living witches were described as gaining power from the moroi condition, while others were believed to cure it.

The moroi embodies fears of invisible forces — illness, envy, or untended spiritual obligations — within close-knit rural life. Unlike the strigoi, which strikes from the grave, the moroi represents danger from within the community. Its legend is tied to explanations for wasting sicknesses long before medical science, and it functions as a reminder of the fragile balance of health, family bonds, and superstition in traditional Romanian villages.

Location:Romania (especially rural southern regions)

Moroi are often paired with strigoi in Romanian belief, but they are distinct. Where the strigoi are undead revenants, **moroi are living beings** — people afflicted by a spiritual condition that drains vitality from others, often unknowingly. A moroi may be a child born with unusual features, a person touched by a curse, or someone who becomes parasitic through misfortune or trauma. In some regions, moroi are said to leave their bodies at night, wandering as ghostlike doubles that feed on the energy of livestock, neighbors, or relatives.

Descriptions vary: some moroi remain physically normal, while others become frail, hollow-eyed, or marked by strange birth signs. Their draining presence manifests in community misfortunes — milk curdling, animals growing weak, children becoming sickly, crops failing. Because the condition can affect infants, families were especially vigilant, placing amulets, garlic, or iron tools near cradles. The boundary between moroi and witch is fluid; some living witches were described as gaining power from the moroi condition, while others were believed to cure it.

The moroi embodies fears of invisible forces — illness, envy, or untended spiritual obligations — within close-knit rural life. Unlike the strigoi, which strikes from the grave, the moroi represents danger from within the community. Its legend is tied to explanations for wasting sicknesses long before medical science, and it functions as a reminder of the fragile balance of health, family bonds, and superstition in traditional Romanian villages.

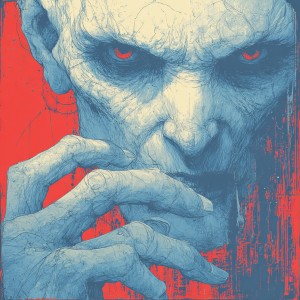

Strigoi

Region: Central & Southeastern Europe

Location:Romania (particularly Transylvania, Wallachia, and Moldavia)

Strigoi are one of the oldest forms of Romanian undead lore — restless spirits or reanimated bodies that rise from the grave because of improper burial, unresolved grievances, or spiritual imbalance. Folklore distinguishes several types: **strigoi vii**, the living witches or shape-shifters who drain vitality, and **strigoi morți**, the undead revenants who walk after death. The undead strigoi can appear pale, gaunt, and shadowy, or fully solid and lifelike, depending on the tale. They are known to leave their graves at night to drink blood, steal life force, or torment relatives. Sometimes they shapeshift into animals — wolves, cats, birds, or insects — adding to their unsettling fluidity.

The origin of the strigoi concept lies in deep ancestral beliefs about the soul’s departure from the body. If burial rituals were incomplete, if someone lived a morally fractured life, or if they died violently, the soul could return. Villages used protective rituals to keep strigoi from rising: sewing the corpse’s mouth shut, driving nails through clothing, laying thorns across the grave, or placing garlic under the tongue. In some regions, if livestock sickened, droughts struck, or children wasted away, villagers suspected a strigoi was active and performed exhumations to identify and “quiet” the revenant.

Strigoi stories reflect fears of disease, famine, and the thin line between the living and the dead in rural communities. They are not refined aristocratic vampires; they are intimate, domestic horrors — a dead family member knocking on the window, a shadow sitting on the chest at night, a corpse found face-down in the grave from restless activity. The strigoi is the rootstock from which modern vampire mythology grew, but in Romania it remains a unique, deeply cultural being tied to family, ritual, and the dangers of liminal death.

Location:Romania (particularly Transylvania, Wallachia, and Moldavia)

Strigoi are one of the oldest forms of Romanian undead lore — restless spirits or reanimated bodies that rise from the grave because of improper burial, unresolved grievances, or spiritual imbalance. Folklore distinguishes several types: **strigoi vii**, the living witches or shape-shifters who drain vitality, and **strigoi morți**, the undead revenants who walk after death. The undead strigoi can appear pale, gaunt, and shadowy, or fully solid and lifelike, depending on the tale. They are known to leave their graves at night to drink blood, steal life force, or torment relatives. Sometimes they shapeshift into animals — wolves, cats, birds, or insects — adding to their unsettling fluidity.

The origin of the strigoi concept lies in deep ancestral beliefs about the soul’s departure from the body. If burial rituals were incomplete, if someone lived a morally fractured life, or if they died violently, the soul could return. Villages used protective rituals to keep strigoi from rising: sewing the corpse’s mouth shut, driving nails through clothing, laying thorns across the grave, or placing garlic under the tongue. In some regions, if livestock sickened, droughts struck, or children wasted away, villagers suspected a strigoi was active and performed exhumations to identify and “quiet” the revenant.

Strigoi stories reflect fears of disease, famine, and the thin line between the living and the dead in rural communities. They are not refined aristocratic vampires; they are intimate, domestic horrors — a dead family member knocking on the window, a shadow sitting on the chest at night, a corpse found face-down in the grave from restless activity. The strigoi is the rootstock from which modern vampire mythology grew, but in Romania it remains a unique, deeply cultural being tied to family, ritual, and the dangers of liminal death.

The Black Forest Werewolves

Region: Central & Southeastern Europe

Location:Black Forest region, southwestern Germany — modern sightings from 20th century onward

The Black Forest has long been associated with wolves, ghosts, and dark folktales, but modern “Black Forest Werewolf” sightings emerged primarily in the late 20th century. Witnesses describe a large, wolf-like humanoid — upright, broad-shouldered, with digitigrade legs, dark fur, and glowing eyes. Sightings occur along rural roads, old logging trails, or deep woodland paths. The creature is said to move with a mix of human-like posture and lupine speed, vanishing quickly when spotted. Many reports come from hunters or late-night drivers who claim the figure crossed the road in two or three strides.

Germany’s medieval werewolf traditions were strong — especially in regions tied to witch hunts and rural fear — but the modern Black Forest werewolf does not function like the cursed villagers of old stories. Instead, it resembles a contemporary cryptid: a liminal, fleeting shape that appears in the periphery of headlights or moonlight. These sightings often occur near abandoned farmhouses, forgotten bunkers, or the dense fir forests that made the region famous. Witnesses frequently describe an intense sense of dread or “wrongness,” similar to U.S. Dogman or Beast of Bray Road encounters.

Whether understood as misidentified wildlife, folklore resonance, or a genuinely unexplained phenomenon, the Black Forest werewolf sits at the crossroads of tradition and modern mystery. It echoes centuries of German fear and fascination with wolves — once common predators, later eradicated, now returning — and adds a new layer of modern myth. Its endurance testifies to the Black Forest’s reputation as one of Europe’s most atmospheric and storied landscapes, where the line between human and wild has always been thin.

Location:Black Forest region, southwestern Germany — modern sightings from 20th century onward

The Black Forest has long been associated with wolves, ghosts, and dark folktales, but modern “Black Forest Werewolf” sightings emerged primarily in the late 20th century. Witnesses describe a large, wolf-like humanoid — upright, broad-shouldered, with digitigrade legs, dark fur, and glowing eyes. Sightings occur along rural roads, old logging trails, or deep woodland paths. The creature is said to move with a mix of human-like posture and lupine speed, vanishing quickly when spotted. Many reports come from hunters or late-night drivers who claim the figure crossed the road in two or three strides.

Germany’s medieval werewolf traditions were strong — especially in regions tied to witch hunts and rural fear — but the modern Black Forest werewolf does not function like the cursed villagers of old stories. Instead, it resembles a contemporary cryptid: a liminal, fleeting shape that appears in the periphery of headlights or moonlight. These sightings often occur near abandoned farmhouses, forgotten bunkers, or the dense fir forests that made the region famous. Witnesses frequently describe an intense sense of dread or “wrongness,” similar to U.S. Dogman or Beast of Bray Road encounters.

Whether understood as misidentified wildlife, folklore resonance, or a genuinely unexplained phenomenon, the Black Forest werewolf sits at the crossroads of tradition and modern mystery. It echoes centuries of German fear and fascination with wolves — once common predators, later eradicated, now returning — and adds a new layer of modern myth. Its endurance testifies to the Black Forest’s reputation as one of Europe’s most atmospheric and storied landscapes, where the line between human and wild has always been thin.

Upyr

Region: Central & Southeastern Europe

Location:Slavic regions — Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, early medieval Eastern Europe

Upyr is one of the earliest recorded vampire-like beings in Slavic tradition — predating many later vampire myths. The Upyr is described as a corpse that rises from the grave to drink blood, spread disease, or attack its own relatives. Unlike later romanticized vampires, the Upyr is bloated, ruddy, and foul-smelling, its face distorted from decomposition. It may appear with glowing eyes, sharp teeth, and swollen limbs. The Upyr leaves its grave at night and returns before dawn, often stirring winds or chills in its wake.

Medieval chronicles mention Upyrs as real dangers. In times of plague or famine, when multiple deaths occurred in a family, villagers sometimes blamed an Upyr — believing the first deceased relative had returned to prey upon the others. The corpse might be exhumed, examined for signs of “feeding,” and ritually destroyed to protect the living. Like many revenant beliefs, Upyr stories stem from attempts to explain sudden death, disease spread, or the disturbing realities of decomposition before modern mortuary practices.

Upyr folklore reflects a deep cultural fear of restless dead — especially those who die violently, unburied, or with unfinished obligations. Its legend shaped later Eastern European vampire myths and influenced the development of the strigoi and other revenant traditions. The Upyr is the primal, raw form of the vampire: a hungry corpse driven not by seduction or glamour but by loneliness, rage, and the clinging remnants of earthly existence.

Location:Slavic regions — Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, early medieval Eastern Europe

Upyr is one of the earliest recorded vampire-like beings in Slavic tradition — predating many later vampire myths. The Upyr is described as a corpse that rises from the grave to drink blood, spread disease, or attack its own relatives. Unlike later romanticized vampires, the Upyr is bloated, ruddy, and foul-smelling, its face distorted from decomposition. It may appear with glowing eyes, sharp teeth, and swollen limbs. The Upyr leaves its grave at night and returns before dawn, often stirring winds or chills in its wake.

Medieval chronicles mention Upyrs as real dangers. In times of plague or famine, when multiple deaths occurred in a family, villagers sometimes blamed an Upyr — believing the first deceased relative had returned to prey upon the others. The corpse might be exhumed, examined for signs of “feeding,” and ritually destroyed to protect the living. Like many revenant beliefs, Upyr stories stem from attempts to explain sudden death, disease spread, or the disturbing realities of decomposition before modern mortuary practices.

Upyr folklore reflects a deep cultural fear of restless dead — especially those who die violently, unburied, or with unfinished obligations. Its legend shaped later Eastern European vampire myths and influenced the development of the strigoi and other revenant traditions. The Upyr is the primal, raw form of the vampire: a hungry corpse driven not by seduction or glamour but by loneliness, rage, and the clinging remnants of earthly existence.

Vila / Vily

Region: Central & Southeastern Europe

Location:Balkans, Carpathian Mountains — Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia, Slovenia, Bulgaria

Vila (plural: Vily) are ethereal mountain nymphs in Slavic folklore — radiant female spirits associated with forests, high meadows, springs, and storms. They appear as tall, luminous women with long flowing hair, often wearing white gowns made of moonlight or mist. In some stories, they have wings; in others, their beauty is so intense it is mistaken for magic. Vily can be fierce warriors, hunters, or dancers, gathering in circles on mountaintops or in forest clearings. Their dances can bless the land — or crush it.

Vily are morally complex. They may heal wounded travelers, protect forests from harm, or reward respectful humans with guidance. But they can also be vengeful: men who spy on them bathing may be blinded or struck dumb; hunters who poach in their sacred spaces may face storms or illness. In some tales, a Vila chooses a human hero to favor, granting him protection in battle or teaching him secret knowledge. But the relationship is perilous — breaking a promise to a Vila can bring a curse that lasts generations.

Vily reflect the Slavic understanding of nature as alive, powerful, and emotionally volatile. They represent the mountain wilderness — breathtaking and deadly, nurturing and unforgiving. Their legends endure because they capture the awe of high places, the mystery of sudden storms, and the ancient belief that beauty itself can be dangerous.

Location:Balkans, Carpathian Mountains — Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia, Slovenia, Bulgaria

Vila (plural: Vily) are ethereal mountain nymphs in Slavic folklore — radiant female spirits associated with forests, high meadows, springs, and storms. They appear as tall, luminous women with long flowing hair, often wearing white gowns made of moonlight or mist. In some stories, they have wings; in others, their beauty is so intense it is mistaken for magic. Vily can be fierce warriors, hunters, or dancers, gathering in circles on mountaintops or in forest clearings. Their dances can bless the land — or crush it.

Vily are morally complex. They may heal wounded travelers, protect forests from harm, or reward respectful humans with guidance. But they can also be vengeful: men who spy on them bathing may be blinded or struck dumb; hunters who poach in their sacred spaces may face storms or illness. In some tales, a Vila chooses a human hero to favor, granting him protection in battle or teaching him secret knowledge. But the relationship is perilous — breaking a promise to a Vila can bring a curse that lasts generations.

Vily reflect the Slavic understanding of nature as alive, powerful, and emotionally volatile. They represent the mountain wilderness — breathtaking and deadly, nurturing and unforgiving. Their legends endure because they capture the awe of high places, the mystery of sudden storms, and the ancient belief that beauty itself can be dangerous.

Wolpertinger

Region: Central & Southeastern Europe

Location:Bavaria (Bavarian Alps and forest villages)

The Wolpertinger is a Bavarian chimera creature whose descriptions vary wildly because it is a creature of pure folk humor. Typically, it is depicted as a small mammal — the body of a hare or squirrel — combined with antlers, wings, fangs, or bird feet. In some versions, it has a duck’s bill; in others, a pheasant’s wings or a deer’s rack. The odd combinations stem from taxidermy pranks in the 19th century, when hunters assembled “hybrid creatures” to amuse tourists, but the idea quickly entered local legend, becoming a tongue-in-cheek part of Bavarian folklore.

According to rural tales, Wolpertingers live in deep forests and alpine meadows, hiding among underbrush or swooping across streams at twilight. They are shy but intelligent, and only reveal themselves to those who are pure of heart — or, in some humorous versions, only after one has drunk a considerable amount of Bavarian beer. Hunters would claim that the best way to see one was to wander at dusk with a lantern and keep completely silent. Some stories say Wolpertingers mate only with others of identical hybrid form, leading to endless variations.

Though rarely treated as a serious cryptid, the Wolpertinger endures because it reflects a uniquely Bavarian blend of mountain superstition, rural humor, and artistic taxidermy. Even today, Bavarian inns and hunting lodges display Wolpertinger mounts as affectionate nods to folklore. It is a creature of play — a reminder that mythmaking can arise from laughter as easily as from fear.

Location:Bavaria (Bavarian Alps and forest villages)

The Wolpertinger is a Bavarian chimera creature whose descriptions vary wildly because it is a creature of pure folk humor. Typically, it is depicted as a small mammal — the body of a hare or squirrel — combined with antlers, wings, fangs, or bird feet. In some versions, it has a duck’s bill; in others, a pheasant’s wings or a deer’s rack. The odd combinations stem from taxidermy pranks in the 19th century, when hunters assembled “hybrid creatures” to amuse tourists, but the idea quickly entered local legend, becoming a tongue-in-cheek part of Bavarian folklore.

According to rural tales, Wolpertingers live in deep forests and alpine meadows, hiding among underbrush or swooping across streams at twilight. They are shy but intelligent, and only reveal themselves to those who are pure of heart — or, in some humorous versions, only after one has drunk a considerable amount of Bavarian beer. Hunters would claim that the best way to see one was to wander at dusk with a lantern and keep completely silent. Some stories say Wolpertingers mate only with others of identical hybrid form, leading to endless variations.

Though rarely treated as a serious cryptid, the Wolpertinger endures because it reflects a uniquely Bavarian blend of mountain superstition, rural humor, and artistic taxidermy. Even today, Bavarian inns and hunting lodges display Wolpertinger mounts as affectionate nods to folklore. It is a creature of play — a reminder that mythmaking can arise from laughter as easily as from fear.

Zmei

Region: Central & Southeastern Europe

Location:Slavic regions — primarily Bulgaria, Serbia, Russia, and Ukraine

The Zmei (also spelled Zmey, Zmaj) is a powerful Slavic dragon, distinct from Western European drakes. Zmei are often multi-headed, winged, and serpent-bodied, but they also possess humanlike intelligence, speech, and emotional depth. In Bulgarian traditions, Zmei may have three, nine, or twelve heads, each capable of breathing fire or controlling storms. They are not always malevolent; some Zmei defend villages from hostile dragons or foul weather spirits, while others abduct maidens, challenge heroes, or demand tribute.

The Zmei’s behavior varies widely depending on region. In some tales, it becomes a lover or protector of a chosen woman, bringing prosperity to her household but danger to the community. In Serbian epics, the Zmaj is associated with thunderstorms and heroic lineage — some heroes are said to descend from unions between humans and Zmei. Battles between Zmei and hostile serpents or devils appear frequently in folklore, symbolizing cosmic conflict between order and chaos.

Zmei stories are deeply tied to Slavic cosmology, in which serpents and dragons reflect elemental power — fire, wind, storm, and fate. They are beings of raw intensity: passionate, jealous, wise, or wrathful depending on the tale. Unlike the purely destructive dragons of Western medieval lore, the Zmei is complex, majestic, and unpredictable, embodying the dangerous beauty of the natural world.

Location:Slavic regions — primarily Bulgaria, Serbia, Russia, and Ukraine

The Zmei (also spelled Zmey, Zmaj) is a powerful Slavic dragon, distinct from Western European drakes. Zmei are often multi-headed, winged, and serpent-bodied, but they also possess humanlike intelligence, speech, and emotional depth. In Bulgarian traditions, Zmei may have three, nine, or twelve heads, each capable of breathing fire or controlling storms. They are not always malevolent; some Zmei defend villages from hostile dragons or foul weather spirits, while others abduct maidens, challenge heroes, or demand tribute.

The Zmei’s behavior varies widely depending on region. In some tales, it becomes a lover or protector of a chosen woman, bringing prosperity to her household but danger to the community. In Serbian epics, the Zmaj is associated with thunderstorms and heroic lineage — some heroes are said to descend from unions between humans and Zmei. Battles between Zmei and hostile serpents or devils appear frequently in folklore, symbolizing cosmic conflict between order and chaos.

Zmei stories are deeply tied to Slavic cosmology, in which serpents and dragons reflect elemental power — fire, wind, storm, and fate. They are beings of raw intensity: passionate, jealous, wise, or wrathful depending on the tale. Unlike the purely destructive dragons of Western medieval lore, the Zmei is complex, majestic, and unpredictable, embodying the dangerous beauty of the natural world.

Comments