CTU: Cryptids-Andean & Southern Cone

El Pishtaco

Region: Andean & Southern Cone

Location:Andes region (Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador)

El Pishtaco is one of the most chilling figures in Andean folklore — a tall, pale stranger who stalks lonely mountain roads, draining the fat from his victims. In Quechua and Aymara culture, body fat represents life, vitality, and spiritual strength, so a being that steals it is committing a profound violation. Early stories describe Pishtacos as white-skinned outsiders who wander at night with sharp knives or strange tools, targeting travelers, shepherds, or people sleeping alone in the puna. To many rural communities, the Pishtaco symbolizes an ever-present fear: the exploitation of Indigenous bodies by foreign powers.

Colonial accounts say the legend took shape during the Spanish conquest, when Indigenous peoples saw conquistadors take human fat to make weapon oil, medicinal salves, or ritual offerings — practices documented in several regions. Later versions adapted to whatever new trauma the Andes experienced: Pishtacos were said to be priests stealing fat for church bells, soldiers using it to grease machinery, or bandits selling it to foreign companies. Every generation reshaped the myth around its own fears. The details vary, but the core image remains: a predatory figure harvesting what makes a person human.

Modern sightings still occur, especially during politically turbulent times. People in remote villages sometimes report strange wanderers or cars without license plates traveling back roads at night. Rumors spread quickly — someone has been taken, the Pishtaco is nearby, warnings go out. These stories aren’t just ghost tales; they reflect centuries of displacement, exploitation, and suspicion of outsiders. The Pishtaco endures because the wound it represents has never fully healed, making him one of the most socially charged legends in Latin America.

Location:Andes region (Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador)

El Pishtaco is one of the most chilling figures in Andean folklore — a tall, pale stranger who stalks lonely mountain roads, draining the fat from his victims. In Quechua and Aymara culture, body fat represents life, vitality, and spiritual strength, so a being that steals it is committing a profound violation. Early stories describe Pishtacos as white-skinned outsiders who wander at night with sharp knives or strange tools, targeting travelers, shepherds, or people sleeping alone in the puna. To many rural communities, the Pishtaco symbolizes an ever-present fear: the exploitation of Indigenous bodies by foreign powers.

Colonial accounts say the legend took shape during the Spanish conquest, when Indigenous peoples saw conquistadors take human fat to make weapon oil, medicinal salves, or ritual offerings — practices documented in several regions. Later versions adapted to whatever new trauma the Andes experienced: Pishtacos were said to be priests stealing fat for church bells, soldiers using it to grease machinery, or bandits selling it to foreign companies. Every generation reshaped the myth around its own fears. The details vary, but the core image remains: a predatory figure harvesting what makes a person human.

Modern sightings still occur, especially during politically turbulent times. People in remote villages sometimes report strange wanderers or cars without license plates traveling back roads at night. Rumors spread quickly — someone has been taken, the Pishtaco is nearby, warnings go out. These stories aren’t just ghost tales; they reflect centuries of displacement, exploitation, and suspicion of outsiders. The Pishtaco endures because the wound it represents has never fully healed, making him one of the most socially charged legends in Latin America.

El Pombero

Region: Andean & Southern Cone

Location:Paraguay, northeast Argentina, southern Brazil (Guaraní regions)

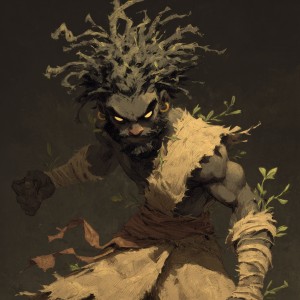

El Pombero — also called *Pombéro* or *Pomberito* — is a central figure in Guaraní folklore: a small, wiry forest spirit known for stealth, mischief, and unpredictability. Usually described as a dark-skinned, shaggy-haired man with long arms and rough, calloused feet, the Pombero moves silently through brush and over dirt roads. Some accounts say he can dislocate his joints to squeeze through impossible spaces; others insist he slips between shadows like smoke. He whistles at night, imitating bird calls, sometimes as a warning, sometimes as a lure. Locals can often identify a Pombero encounter by the sudden quiet of animals or the feeling of being watched from just beyond lamplight.

His behavior ranges from helpful to dangerous depending on how he is treated. When respected, Pombero protects livestock, defends fields from thieves, and ensures good fortune for farmers. People traditionally leave offerings — tobacco, caña (sugarcane liquor), or fresh bread — on windowsills or fence posts to remain in his good graces. Neglect him, however, and the Pombero becomes a tormentor: letting livestock loose, braiding horses’ manes into impossible knots, stealing tools, or mimicking voices to frighten those who walk alone at night. His pranks can turn menacing, and stories warn that he does not forgive easily when offended.

One of the most controversial parts of Pombero folklore involves his interactions with women. Some stories portray him as a voyeur who slips into bedrooms through cracks or gaps in walls; others go further, implying that he fathers children, similar to the boto of Amazonian lore. In rural communities, children with distinctive features or unexplained parentage were sometimes said to be “hijos del Pombero.” While these interpretations reflect cultural anxieties rather than literal belief, they show how deeply the Pombero legend permeates social life. Above all, he embodies the unseen forces of the forest — watchful, capricious, and very aware of who respects the old pacts.

Location:Paraguay, northeast Argentina, southern Brazil (Guaraní regions)

El Pombero — also called *Pombéro* or *Pomberito* — is a central figure in Guaraní folklore: a small, wiry forest spirit known for stealth, mischief, and unpredictability. Usually described as a dark-skinned, shaggy-haired man with long arms and rough, calloused feet, the Pombero moves silently through brush and over dirt roads. Some accounts say he can dislocate his joints to squeeze through impossible spaces; others insist he slips between shadows like smoke. He whistles at night, imitating bird calls, sometimes as a warning, sometimes as a lure. Locals can often identify a Pombero encounter by the sudden quiet of animals or the feeling of being watched from just beyond lamplight.

His behavior ranges from helpful to dangerous depending on how he is treated. When respected, Pombero protects livestock, defends fields from thieves, and ensures good fortune for farmers. People traditionally leave offerings — tobacco, caña (sugarcane liquor), or fresh bread — on windowsills or fence posts to remain in his good graces. Neglect him, however, and the Pombero becomes a tormentor: letting livestock loose, braiding horses’ manes into impossible knots, stealing tools, or mimicking voices to frighten those who walk alone at night. His pranks can turn menacing, and stories warn that he does not forgive easily when offended.

One of the most controversial parts of Pombero folklore involves his interactions with women. Some stories portray him as a voyeur who slips into bedrooms through cracks or gaps in walls; others go further, implying that he fathers children, similar to the boto of Amazonian lore. In rural communities, children with distinctive features or unexplained parentage were sometimes said to be “hijos del Pombero.” While these interpretations reflect cultural anxieties rather than literal belief, they show how deeply the Pombero legend permeates social life. Above all, he embodies the unseen forces of the forest — watchful, capricious, and very aware of who respects the old pacts.

El Trauco

Region: Andean & Southern Cone

Location:Southern Chile (especially Chiloé Archipelago)

El Trauco is one of the most infamous figures in Chilean folklore, particularly in the islands of Chiloé, where myth and daily life intertwine deeply. He is described as a small, dwarf-like man with a deformed face, coarse features, and legs twisted as if broken at the knees. He wears rustic clothing made of moss or bark and carries a stone hatchet believed to hold supernatural power. Despite his frightening appearance, El Trauco is said to have an irresistible magical influence on women. According to tradition, no woman can refuse him; his presence creates overpowering compulsion and trance-like vulnerability.

Folklore often frames El Trauco as an explanation for unexpected pregnancies in isolated rural communities. If a young woman becomes pregnant without an acknowledged partner, families sometimes attribute it to El Trauco’s influence rather than accusing her of impropriety. This doesn’t mean the being is considered benign — he is feared for his unpredictable nature. Some stories claim he can kill a man with a single strike of his stone hatchet or merely by staring at him, while others depict him as more of a wandering spirit who seeks out vulnerable women in forests or by riverbanks.

El Trauco’s legend reflects the Chiloé islands’ long tradition of supernatural beings closely tied to the landscape. Dense forests, foggy coastlines, and isolated settlements shaped a worldview where the natural world holds spirits that influence human life in intimate ways. Today, the legend persists in rural areas, kept alive through cautionary tales, whispered stories among elders, and the island’s dramatic storytelling culture. El Trauco remains one of Chile’s most unsettling supernatural figures — not monstrous in size or shape, but in the quiet inevitability of his influence.

Location:Southern Chile (especially Chiloé Archipelago)

El Trauco is one of the most infamous figures in Chilean folklore, particularly in the islands of Chiloé, where myth and daily life intertwine deeply. He is described as a small, dwarf-like man with a deformed face, coarse features, and legs twisted as if broken at the knees. He wears rustic clothing made of moss or bark and carries a stone hatchet believed to hold supernatural power. Despite his frightening appearance, El Trauco is said to have an irresistible magical influence on women. According to tradition, no woman can refuse him; his presence creates overpowering compulsion and trance-like vulnerability.

Folklore often frames El Trauco as an explanation for unexpected pregnancies in isolated rural communities. If a young woman becomes pregnant without an acknowledged partner, families sometimes attribute it to El Trauco’s influence rather than accusing her of impropriety. This doesn’t mean the being is considered benign — he is feared for his unpredictable nature. Some stories claim he can kill a man with a single strike of his stone hatchet or merely by staring at him, while others depict him as more of a wandering spirit who seeks out vulnerable women in forests or by riverbanks.

El Trauco’s legend reflects the Chiloé islands’ long tradition of supernatural beings closely tied to the landscape. Dense forests, foggy coastlines, and isolated settlements shaped a worldview where the natural world holds spirits that influence human life in intimate ways. Today, the legend persists in rural areas, kept alive through cautionary tales, whispered stories among elders, and the island’s dramatic storytelling culture. El Trauco remains one of Chile’s most unsettling supernatural figures — not monstrous in size or shape, but in the quiet inevitability of his influence.

The Acarí

Region: Andean & Southern Cone

Location:Andes foothills and Amazon fringes (Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador)

The Acarí is a lesser-known but persistent legend describing enormous bats said to inhabit remote caves and high cliffs. Reports portray them as creatures with wingspans up to ten feet, leathery bodies, and faces that resemble exaggerated vampire bats with long snouts and sharp teeth. Some stories claim their eyes glow red in torchlight; others describe them as silent shadows gliding through the dusk. The Acarí often appear around abandoned mines, ravines, or deep forest edges, where their shrill cries echo like a child’s wail or a piercing whistle.

Although the giant bat image seems fantastical, it may stem from real encounters with large species of fruit bats or with owls that appear enormous in low light. To Indigenous and rural communities, however, the Acarí is more than a misidentified animal — it is a warning presence. People tell stories of miners chased from tunnels by broad-winged creatures, or of hunters who feel a sudden rush of wind as something massive passes overhead in the dark. The Acarí is said to feed on small animals or livestock, though some tales claim it drinks blood from goats or llamas, linking it to vampiric folklore.

Because bats are often associated with underworld symbols in pre-Columbian mythology, the Acarí occupies a liminal space between creature and omen. It reflects fear of places where humans do not belong — deep caves, unlit ravines, and forgotten paths. Its existence in folklore reminds locals that the wilderness has its own guardians and dangers, especially at night. Whether a giant species, a misinterpretation, or a symbol, the Acarí remains one of the most atmospheric figures in Andean fringe mythology.

Location:Andes foothills and Amazon fringes (Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador)

The Acarí is a lesser-known but persistent legend describing enormous bats said to inhabit remote caves and high cliffs. Reports portray them as creatures with wingspans up to ten feet, leathery bodies, and faces that resemble exaggerated vampire bats with long snouts and sharp teeth. Some stories claim their eyes glow red in torchlight; others describe them as silent shadows gliding through the dusk. The Acarí often appear around abandoned mines, ravines, or deep forest edges, where their shrill cries echo like a child’s wail or a piercing whistle.

Although the giant bat image seems fantastical, it may stem from real encounters with large species of fruit bats or with owls that appear enormous in low light. To Indigenous and rural communities, however, the Acarí is more than a misidentified animal — it is a warning presence. People tell stories of miners chased from tunnels by broad-winged creatures, or of hunters who feel a sudden rush of wind as something massive passes overhead in the dark. The Acarí is said to feed on small animals or livestock, though some tales claim it drinks blood from goats or llamas, linking it to vampiric folklore.

Because bats are often associated with underworld symbols in pre-Columbian mythology, the Acarí occupies a liminal space between creature and omen. It reflects fear of places where humans do not belong — deep caves, unlit ravines, and forgotten paths. Its existence in folklore reminds locals that the wilderness has its own guardians and dangers, especially at night. Whether a giant species, a misinterpretation, or a symbol, the Acarí remains one of the most atmospheric figures in Andean fringe mythology.

Comments