CTU: Cryptids-Africa

Aisha Qandisha

Region: Africa

Location:Morocco (especially rural and coastal regions), Moroccan Jewish and Amazigh traditions

Aisha Qandisha — also known as Lalla Aisha — is one of Morocco’s most powerful and feared female spirits. Often depicted as an extraordinarily beautiful woman with long hair, she sometimes hides goat-like or camel-like legs beneath her garments. Men who encounter her in isolated places — canals, abandoned buildings, crossroads at dusk — say she appears seductive and ethereal. But once ensnared by her beauty, victims are struck by paralysis, madness, or obsessive infatuation. In some stories she drains vitality; in others she binds the victim to her through spiritual influence.

Unlike many folkloric seductresses, Aisha Qandisha has deep cultural roots tied to Morocco’s layered history. Some believe she originates from pre-Islamic Amazigh water spirits; others connect her to trauma from wartime resistance against Portuguese colonization. Over centuries, she became a complex figure associated with water, desire, and dangerous enchantment. Victims of her influence are said to become withdrawn, haunted, or unable to maintain relationships. Families often turn to *gnawa* or *hadhra* ceremonies — musical and ritual performances designed to negotiate with or appease powerful spirits.

Despite her fearsome reputation, Aisha Qandisha is not universally malevolent. Some stories say she protects women, punishes abusive men, or aids those who show her respect. She embodies the liminal space between beauty and danger, water and desert, desire and destruction. For many Moroccans, she represents an older world of spirits that still intersects with modern life — a reminder that the unseen remains potent in everyday places.

Location:Morocco (especially rural and coastal regions), Moroccan Jewish and Amazigh traditions

Aisha Qandisha — also known as Lalla Aisha — is one of Morocco’s most powerful and feared female spirits. Often depicted as an extraordinarily beautiful woman with long hair, she sometimes hides goat-like or camel-like legs beneath her garments. Men who encounter her in isolated places — canals, abandoned buildings, crossroads at dusk — say she appears seductive and ethereal. But once ensnared by her beauty, victims are struck by paralysis, madness, or obsessive infatuation. In some stories she drains vitality; in others she binds the victim to her through spiritual influence.

Unlike many folkloric seductresses, Aisha Qandisha has deep cultural roots tied to Morocco’s layered history. Some believe she originates from pre-Islamic Amazigh water spirits; others connect her to trauma from wartime resistance against Portuguese colonization. Over centuries, she became a complex figure associated with water, desire, and dangerous enchantment. Victims of her influence are said to become withdrawn, haunted, or unable to maintain relationships. Families often turn to *gnawa* or *hadhra* ceremonies — musical and ritual performances designed to negotiate with or appease powerful spirits.

Despite her fearsome reputation, Aisha Qandisha is not universally malevolent. Some stories say she protects women, punishes abusive men, or aids those who show her respect. She embodies the liminal space between beauty and danger, water and desert, desire and destruction. For many Moroccans, she represents an older world of spirits that still intersects with modern life — a reminder that the unseen remains potent in everyday places.

Aziza

Region: Africa

Location:Benin, Togo, and broader Dahomey region (Fon and Ewe traditions)

Aziza are small, luminous forest spirits found in the traditions of the Fon people of Benin and neighboring Ewe cultures. They are described as tiny, humanlike beings who live in anthills, silk-cotton trees, or deep within leafy forests. Aziza are usually invisible to humans unless they choose to appear; when visible, they are sometimes depicted as child-sized figures with a faint glow or the shimmer of fireflies. Their presence is tied to knowledge, craft, and survival — they are guardians of forest wisdom, not tricksters or predators.

Tradition holds that the Aziza taught early humans essential skills. Stories speak of them passing on secrets of hunting, fire-making, herbal medicine, and protective magic. Hunters who earned their trust received guidance through dreams or sudden intuitions, such as when to track, where to set traps, or how to read signs in the bush. The Aziza are said to reward humility and respect for the forest. Those who treat the land with care might find helpful signs, like fresh water in a drought or safe passage through dense brush.

But the Aziza are also shy and easily offended. They avoid places where the forest has been disrespected — overhunted, burned, or cleared without ritual acknowledgment. Offenders might experience misfortune: tools vanishing, paths twisting, or sudden illness after disturbing an anthill believed to hold Aziza dwellings. Their stories endure because they embody the spiritual ecology of the region — a belief that the forest is alive, aware, and inhabited by small but powerful protectors.

Location:Benin, Togo, and broader Dahomey region (Fon and Ewe traditions)

Aziza are small, luminous forest spirits found in the traditions of the Fon people of Benin and neighboring Ewe cultures. They are described as tiny, humanlike beings who live in anthills, silk-cotton trees, or deep within leafy forests. Aziza are usually invisible to humans unless they choose to appear; when visible, they are sometimes depicted as child-sized figures with a faint glow or the shimmer of fireflies. Their presence is tied to knowledge, craft, and survival — they are guardians of forest wisdom, not tricksters or predators.

Tradition holds that the Aziza taught early humans essential skills. Stories speak of them passing on secrets of hunting, fire-making, herbal medicine, and protective magic. Hunters who earned their trust received guidance through dreams or sudden intuitions, such as when to track, where to set traps, or how to read signs in the bush. The Aziza are said to reward humility and respect for the forest. Those who treat the land with care might find helpful signs, like fresh water in a drought or safe passage through dense brush.

But the Aziza are also shy and easily offended. They avoid places where the forest has been disrespected — overhunted, burned, or cleared without ritual acknowledgment. Offenders might experience misfortune: tools vanishing, paths twisting, or sudden illness after disturbing an anthill believed to hold Aziza dwellings. Their stories endure because they embody the spiritual ecology of the region — a belief that the forest is alive, aware, and inhabited by small but powerful protectors.

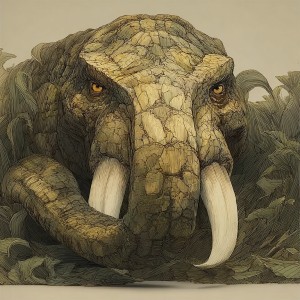

Emela-Ntouka

Region: Africa

Location:Congo Basin (Likouala region; folklore of the Mbo, Aka, and other forest peoples)

Emela-Ntouka, meaning “killer of elephants,” is a legendary swamp-dwelling creature said to inhabit the deep Congo Basin. It is described as a large, rhinoceros-like animal with a massive horn — but unlike a rhino, its horn is often portrayed as smooth, straight, and dangerous enough to pierce elephants with a single blow. Some accounts say it is reddish-brown, others gray or mud-colored. Witnesses describe it as semi-aquatic, preferring rivers, marshes, and flooded forest, where it emerges to graze or attack those who come too close.

Local hunters and forest peoples emphasize Emela-Ntouka’s aggression. It is feared for its ability to overturn boats, charge with incredible force, and kill other large animals — especially elephants, which it reportedly attacks to defend territory. Unlike Mokele-Mbembe (another Congo cryptid linked to peaceful herbivores), Emela-Ntouka is always framed as deadly. Folklore says it bellows loudly when threatened, a sound like a deep, resonant horn echoing across the swamp. Some say its presence causes smaller animals to flee and birds to fall silent.

Although there is no scientific evidence of Emela-Ntouka, the legend persists because it reflects real dangers of the Congo: territorial hippos, hidden sandbars, and dense swamp that conceals large animals. The creature serves as a warning to avoid certain waterways or to treat the swamp with respect. Its image — part rhino, part primordial beast — illustrates the vastness and unknowability of Central Africa’s interior.

Location:Congo Basin (Likouala region; folklore of the Mbo, Aka, and other forest peoples)

Emela-Ntouka, meaning “killer of elephants,” is a legendary swamp-dwelling creature said to inhabit the deep Congo Basin. It is described as a large, rhinoceros-like animal with a massive horn — but unlike a rhino, its horn is often portrayed as smooth, straight, and dangerous enough to pierce elephants with a single blow. Some accounts say it is reddish-brown, others gray or mud-colored. Witnesses describe it as semi-aquatic, preferring rivers, marshes, and flooded forest, where it emerges to graze or attack those who come too close.

Local hunters and forest peoples emphasize Emela-Ntouka’s aggression. It is feared for its ability to overturn boats, charge with incredible force, and kill other large animals — especially elephants, which it reportedly attacks to defend territory. Unlike Mokele-Mbembe (another Congo cryptid linked to peaceful herbivores), Emela-Ntouka is always framed as deadly. Folklore says it bellows loudly when threatened, a sound like a deep, resonant horn echoing across the swamp. Some say its presence causes smaller animals to flee and birds to fall silent.

Although there is no scientific evidence of Emela-Ntouka, the legend persists because it reflects real dangers of the Congo: territorial hippos, hidden sandbars, and dense swamp that conceals large animals. The creature serves as a warning to avoid certain waterways or to treat the swamp with respect. Its image — part rhino, part primordial beast — illustrates the vastness and unknowability of Central Africa’s interior.

Grootslang

Region: Africa

Location:Northern Cape, South Africa (Richtersveld caves), with related mining-camp legends extending into West African diamond lore

The Grootslang — Afrikaans for “great snake” — is a massive, primeval creature said to inhabit deep caves and rocky ravines of the Richtersveld. In legend, it was one of the first beings created by the gods, who mistakenly gave it too much strength and cunning. Realizing the error, the gods split the creature into two species — elephants and snakes. But one original Grootslang escaped the process and fled into the earth, where it multiplied and persists to this day. Descriptions portray it as an enormous serpent, sometimes with elephant-like features such as tusks or a massive head.

Stories place the Grootslang deep within the so-called “Wonder Hole” or “Bottomless Pit,” a cavern believed to connect to underground tunnels stretching across Africa. The creature is said to hoard diamonds and precious stones — a detail that blends indigenous lore with colonial-era mining myth. Travelers who sought wealth in the wilderness were warned that the Grootslang could lure them with glittering gems only to devour them. Its eyes reportedly glow like lanterns in the dark, and its roar echoes through stone passages.

The legend reflects both the harsh terrain and the dangers of diamond-rush greed. Early prospectors in South Africa and later laborers in West African mines adopted the Grootslang as a symbol of hidden dangers beneath the earth. To local communities, it also represents a primordial force older than humanity — a reminder that deep caves and untouched landscapes have their own guardians, far beyond human control or comprehension.

Location:Northern Cape, South Africa (Richtersveld caves), with related mining-camp legends extending into West African diamond lore

The Grootslang — Afrikaans for “great snake” — is a massive, primeval creature said to inhabit deep caves and rocky ravines of the Richtersveld. In legend, it was one of the first beings created by the gods, who mistakenly gave it too much strength and cunning. Realizing the error, the gods split the creature into two species — elephants and snakes. But one original Grootslang escaped the process and fled into the earth, where it multiplied and persists to this day. Descriptions portray it as an enormous serpent, sometimes with elephant-like features such as tusks or a massive head.

Stories place the Grootslang deep within the so-called “Wonder Hole” or “Bottomless Pit,” a cavern believed to connect to underground tunnels stretching across Africa. The creature is said to hoard diamonds and precious stones — a detail that blends indigenous lore with colonial-era mining myth. Travelers who sought wealth in the wilderness were warned that the Grootslang could lure them with glittering gems only to devour them. Its eyes reportedly glow like lanterns in the dark, and its roar echoes through stone passages.

The legend reflects both the harsh terrain and the dangers of diamond-rush greed. Early prospectors in South Africa and later laborers in West African mines adopted the Grootslang as a symbol of hidden dangers beneath the earth. To local communities, it also represents a primordial force older than humanity — a reminder that deep caves and untouched landscapes have their own guardians, far beyond human control or comprehension.

Ifrit

Region: Africa

Location:North Africa, the Sahara, Arabian Peninsula (Islamic and pre-Islamic lore)

The Ifrit is one of the most powerful and fearsome categories of jinn in Islamic folklore. Described as beings of smokeless fire, Ifrit are immense, strong, and highly intelligent, dwelling in deserts, ruins, and underground places. They often appear as towering, flame-wreathed figures or as shadows with burning eyes. But like all jinn, they are shape-shifters capable of taking human or animal forms. Ifrit are not inherently evil, but they are known for their rebelliousness, pride, and independence — qualities that make them formidable adversaries or unpredictable allies.

In Islamic texts and stories, Ifrit often appear as beings who resist humans or test their limits. Some act as guardians of treasure, sacred places, or ancient secrets. Others seek vengeance for wrongdoing or punish arrogance. They possess immense magical ability — flight, invisibility, illusion, and manipulation of fire. While exorcists and religious scholars can negotiate with lesser jinn, facing an Ifrit requires extraordinary spiritual strength. Their name is sometimes used as a warning: a place haunted by an Ifrit should be avoided.

Culturally, Ifrit represent the dangers of hubris, temptation, and greed. Many North African and Middle Eastern tales warn travelers not to disturb abandoned wells, sand-buried ruins, or lonely desert crossroads for fear of awakening an Ifrit. In urban folklore, Ifrit sometimes appear as nighttime terrors or figures who punish immoral behavior. Their wide geographic presence and deep mythology make them one of the most enduring supernatural archetypes of the Islamic world.

Location:North Africa, the Sahara, Arabian Peninsula (Islamic and pre-Islamic lore)

The Ifrit is one of the most powerful and fearsome categories of jinn in Islamic folklore. Described as beings of smokeless fire, Ifrit are immense, strong, and highly intelligent, dwelling in deserts, ruins, and underground places. They often appear as towering, flame-wreathed figures or as shadows with burning eyes. But like all jinn, they are shape-shifters capable of taking human or animal forms. Ifrit are not inherently evil, but they are known for their rebelliousness, pride, and independence — qualities that make them formidable adversaries or unpredictable allies.

In Islamic texts and stories, Ifrit often appear as beings who resist humans or test their limits. Some act as guardians of treasure, sacred places, or ancient secrets. Others seek vengeance for wrongdoing or punish arrogance. They possess immense magical ability — flight, invisibility, illusion, and manipulation of fire. While exorcists and religious scholars can negotiate with lesser jinn, facing an Ifrit requires extraordinary spiritual strength. Their name is sometimes used as a warning: a place haunted by an Ifrit should be avoided.

Culturally, Ifrit represent the dangers of hubris, temptation, and greed. Many North African and Middle Eastern tales warn travelers not to disturb abandoned wells, sand-buried ruins, or lonely desert crossroads for fear of awakening an Ifrit. In urban folklore, Ifrit sometimes appear as nighttime terrors or figures who punish immoral behavior. Their wide geographic presence and deep mythology make them one of the most enduring supernatural archetypes of the Islamic world.

Impundulu the Lightning Bird

Region: Africa

Location:Southern Africa (Zulu, Xhosa, and Pedi traditions)

The Impundulu — “lightning bird” — is a powerful being associated with storms, lightning, and witchcraft. It is said to appear as a massive bird, often black-and-white, with feathers that shimmer like storm clouds. Some stories describe it as large enough to carry off goats; others emphasize its electrical nature, saying lightning strikes mark its landing spots. When it stomps or flaps its wings, thunder follows. It serves as the familiar of certain witches or spiritual practitioners, acting as both servant and weapon.

In many versions, the Impundulu is immortal, passing from witch to witch across generations. It can drink blood and sometimes appears in human form as a handsome stranger who seduces victims. Its appetite for blood links it to vampiric folklore, though its primary association is weather — calling storms, directing lightning, and bringing destruction or fertility depending on the witch’s intent. Some stories portray the bird as obedient; others suggest it has its own will and may turn on a careless master.

For rural communities, the Impundulu explained the violence of sudden storms, lightning-caused fires, and the mysterious injuries left by powerful electrical strikes. Even today, elders speak of certain storm patterns or odd scorch marks as signs of the lightning bird’s presence. Its reputation as both dangerous and awe-inspiring makes it one of the most iconic beings of Southern African folklore — a creature that embodies the raw, unpredictable power of the sky.

Location:Southern Africa (Zulu, Xhosa, and Pedi traditions)

The Impundulu — “lightning bird” — is a powerful being associated with storms, lightning, and witchcraft. It is said to appear as a massive bird, often black-and-white, with feathers that shimmer like storm clouds. Some stories describe it as large enough to carry off goats; others emphasize its electrical nature, saying lightning strikes mark its landing spots. When it stomps or flaps its wings, thunder follows. It serves as the familiar of certain witches or spiritual practitioners, acting as both servant and weapon.

In many versions, the Impundulu is immortal, passing from witch to witch across generations. It can drink blood and sometimes appears in human form as a handsome stranger who seduces victims. Its appetite for blood links it to vampiric folklore, though its primary association is weather — calling storms, directing lightning, and bringing destruction or fertility depending on the witch’s intent. Some stories portray the bird as obedient; others suggest it has its own will and may turn on a careless master.

For rural communities, the Impundulu explained the violence of sudden storms, lightning-caused fires, and the mysterious injuries left by powerful electrical strikes. Even today, elders speak of certain storm patterns or odd scorch marks as signs of the lightning bird’s presence. Its reputation as both dangerous and awe-inspiring makes it one of the most iconic beings of Southern African folklore — a creature that embodies the raw, unpredictable power of the sky.

Kongamato

Region: Africa

Location:Zambia, Angola, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (swamps, rivers, and wetlands)

Kongamato — meaning “breaker of boats” in some Bantu dialects — is a fearsome flying creature said to inhabit the remote swamps and river systems of Central Africa. Eyewitness descriptions typically portray it as a large, leathery-winged reptile resembling a pterosaur, with a wingspan between four and seven feet, a long beak filled with teeth, and reddish or black skin. It is said to fly low over the water, attacking canoeists or fishermen who enter its territory, overturning boats with its wings or lunging from the air with startling speed.

In local folklore, Kongamato is not a dinosaur but a dangerous river guardian. It inhabits areas where humans rarely venture — vast reedbeds, flooded plains, and deep channels where visibility is low. People say it reacts aggressively to bright colors, especially red, and that its eyes glow in twilight. Colonial explorers in the early 20th century encountered consistent stories from different tribes, and several accounts describe injuries on travelers that locals attributed to Kongamato attacks. These sightings fueled speculation about a living prehistoric creature, but the legend has always held cultural weight far beyond cryptozoology.

To the peoples of the region, Kongamato embodies the terror of entering unknown wetlands — places filled with crocodiles, poisonous snakes, and treacherous currents. It personifies the fear of being overturned and swallowed by the swamp. Even today, the creature appears in local cautionary tales, warning travelers to respect rivers during flood season, avoid sacred or taboo waterways, and never assume that wilderness has no guardians.

Location:Zambia, Angola, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (swamps, rivers, and wetlands)

Kongamato — meaning “breaker of boats” in some Bantu dialects — is a fearsome flying creature said to inhabit the remote swamps and river systems of Central Africa. Eyewitness descriptions typically portray it as a large, leathery-winged reptile resembling a pterosaur, with a wingspan between four and seven feet, a long beak filled with teeth, and reddish or black skin. It is said to fly low over the water, attacking canoeists or fishermen who enter its territory, overturning boats with its wings or lunging from the air with startling speed.

In local folklore, Kongamato is not a dinosaur but a dangerous river guardian. It inhabits areas where humans rarely venture — vast reedbeds, flooded plains, and deep channels where visibility is low. People say it reacts aggressively to bright colors, especially red, and that its eyes glow in twilight. Colonial explorers in the early 20th century encountered consistent stories from different tribes, and several accounts describe injuries on travelers that locals attributed to Kongamato attacks. These sightings fueled speculation about a living prehistoric creature, but the legend has always held cultural weight far beyond cryptozoology.

To the peoples of the region, Kongamato embodies the terror of entering unknown wetlands — places filled with crocodiles, poisonous snakes, and treacherous currents. It personifies the fear of being overturned and swallowed by the swamp. Even today, the creature appears in local cautionary tales, warning travelers to respect rivers during flood season, avoid sacred or taboo waterways, and never assume that wilderness has no guardians.

Mami Wata

Region: Africa

Location:West and Central Africa (Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Congo), with influence across the African diaspora

Mami Wata is one of Africa’s most widespread and enduring water spirits — a being associated with beauty, allure, wealth, danger, and the unpredictable power of rivers and oceans. Often depicted as a stunning woman with long hair, sometimes with the lower body of a serpent or accompanied by snakes, Mami Wata embodies both seduction and mystery. In some regions, she appears as a mermaid figure; in others, she shifts between human and aquatic forms. Her gaze is said to be mesmerizing, drawing people toward her with promises of wealth, healing, or deeper spiritual knowledge.

Encounters with Mami Wata in stories often involve bargains. She may offer prosperity, skill, or magical knowledge, but the agreement requires strict devotion — ritual cleanliness, abstinence, or secrecy. Those who break the pact may suffer misfortune, illness, or madness. In many traditions, those taken by Mami Wata disappear beneath the water, only to return days or weeks later transformed — becoming healers, diviners, or spiritually sensitive individuals. These experiences are interpreted not as possession but as initiation.

Mami Wata’s imagery evolved over centuries through contact with Indian Ocean trade, European artists, and African reinterpretation. As a result, she embodies layers of cultural exchange: Indigenous river spirits, global mermaid motifs, serpentine deities, and modern Afro-diasporic spirituality. Today she is a central figure in syncretic religions, healing ceremonies, and artistic expression. Her power lies in her dual nature — giver of wealth and taker of sanity, healer and seducer, mirror of human desire and reminder of water’s unpredictable strength.

Location:West and Central Africa (Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Congo), with influence across the African diaspora

Mami Wata is one of Africa’s most widespread and enduring water spirits — a being associated with beauty, allure, wealth, danger, and the unpredictable power of rivers and oceans. Often depicted as a stunning woman with long hair, sometimes with the lower body of a serpent or accompanied by snakes, Mami Wata embodies both seduction and mystery. In some regions, she appears as a mermaid figure; in others, she shifts between human and aquatic forms. Her gaze is said to be mesmerizing, drawing people toward her with promises of wealth, healing, or deeper spiritual knowledge.

Encounters with Mami Wata in stories often involve bargains. She may offer prosperity, skill, or magical knowledge, but the agreement requires strict devotion — ritual cleanliness, abstinence, or secrecy. Those who break the pact may suffer misfortune, illness, or madness. In many traditions, those taken by Mami Wata disappear beneath the water, only to return days or weeks later transformed — becoming healers, diviners, or spiritually sensitive individuals. These experiences are interpreted not as possession but as initiation.

Mami Wata’s imagery evolved over centuries through contact with Indian Ocean trade, European artists, and African reinterpretation. As a result, she embodies layers of cultural exchange: Indigenous river spirits, global mermaid motifs, serpentine deities, and modern Afro-diasporic spirituality. Today she is a central figure in syncretic religions, healing ceremonies, and artistic expression. Her power lies in her dual nature — giver of wealth and taker of sanity, healer and seducer, mirror of human desire and reminder of water’s unpredictable strength.

Nandi Bear

Region: Africa

Location:Kenya (Nandi region), Western Kenya highlands, Rift Valley fringes

The Nandi Bear is a legendary carnivorous animal said to inhabit the highlands of western Kenya. Descriptions vary, but it is typically portrayed as a large, hyena-like or bear-like creature with a sloping back, powerful forequarters, and a frightening temper. Witnesses describe it as reddish, tawny, or dark brown, with a massive head and long claws capable of tearing through huts or livestock pens. Unlike lions or hyenas, the Nandi Bear is said to attack without provocation, often targeting solitary travelers or livestock before vanishing into thick brush.

Stories about the Nandi Bear rose dramatically in the early 20th century during colonial expansion into highland regions. European settlers, local workers, and Kenyan tribes all reported sightings, sometimes blaming mysterious killings on the creature. The Nandi people had older names for similar beings — such as *Chemosit* — blending folklore with early zoological curiosity. Accounts consistently emphasize its ferocity: the Nandi Bear attacks with stunning speed, aims for the head, and leaves behind mutilated carcasses that don’t match known predators’ patterns.

Explanations for the legend range from misidentified hyenas to surviving prehistoric mammals like the chalicothere — but no scientific evidence has ever surfaced. In local folklore, the Nandi Bear embodies the fear of solitary travel, the unknown edges of wilderness, and the dangers of crossing into territories where humans are not dominant. Whether cryptid or cautionary figure, it remains one of Africa’s most enduring wildland mysteries.

Location:Kenya (Nandi region), Western Kenya highlands, Rift Valley fringes

The Nandi Bear is a legendary carnivorous animal said to inhabit the highlands of western Kenya. Descriptions vary, but it is typically portrayed as a large, hyena-like or bear-like creature with a sloping back, powerful forequarters, and a frightening temper. Witnesses describe it as reddish, tawny, or dark brown, with a massive head and long claws capable of tearing through huts or livestock pens. Unlike lions or hyenas, the Nandi Bear is said to attack without provocation, often targeting solitary travelers or livestock before vanishing into thick brush.

Stories about the Nandi Bear rose dramatically in the early 20th century during colonial expansion into highland regions. European settlers, local workers, and Kenyan tribes all reported sightings, sometimes blaming mysterious killings on the creature. The Nandi people had older names for similar beings — such as *Chemosit* — blending folklore with early zoological curiosity. Accounts consistently emphasize its ferocity: the Nandi Bear attacks with stunning speed, aims for the head, and leaves behind mutilated carcasses that don’t match known predators’ patterns.

Explanations for the legend range from misidentified hyenas to surviving prehistoric mammals like the chalicothere — but no scientific evidence has ever surfaced. In local folklore, the Nandi Bear embodies the fear of solitary travel, the unknown edges of wilderness, and the dangers of crossing into territories where humans are not dominant. Whether cryptid or cautionary figure, it remains one of Africa’s most enduring wildland mysteries.

Ogogo Water Panther

Region: Africa

Location:Kenya and Uganda (various lakes and deep rivers; Luo and neighboring traditions)

The Ogogo — sometimes called a Water Panther in comparative East African folklore — is a powerful aquatic being believed to dwell in deep lakes and river bends. Descriptions vary, but many portray it as a sleek, panther-like creature with scales instead of fur, luminous eyes, and a long, whip-like tail. Other accounts emphasize a horned head, suggesting a hybrid between a big cat and a reptile. The Ogogo moves silently beneath the surface, surfacing only during storms or when angered by human disturbances.

In Luo and neighboring cultures, the Ogogo is often linked to stories of disappearances at lakes and floods that destroy settlements. It represents the unpredictable power of water — not simply a monster, but a guardian of sacred or dangerous places. Elders say the Ogogo can overturn boats, drag swimmers to the depths, or appear in dreams to warn of ecological imbalance. Fishermen traditionally offered libations or prayers before entering waters rumored to be Ogogo territory, acknowledging the being’s presence and asking permission to cross.

Like many African water spirits, the Ogogo exists at the intersection of metaphor and observation: fierce animals like hippos, crocodiles, or leopards near rivers likely influenced the being’s characteristics. But the emphasis on glowing eyes, storms, and supernatural agency suggests a deeper symbolism — the recognition that water is both life-giving and deadly, and must be approached with respect. The Ogogo endures as a reminder that hidden forces dwell beneath still waters.

Location:Kenya and Uganda (various lakes and deep rivers; Luo and neighboring traditions)

The Ogogo — sometimes called a Water Panther in comparative East African folklore — is a powerful aquatic being believed to dwell in deep lakes and river bends. Descriptions vary, but many portray it as a sleek, panther-like creature with scales instead of fur, luminous eyes, and a long, whip-like tail. Other accounts emphasize a horned head, suggesting a hybrid between a big cat and a reptile. The Ogogo moves silently beneath the surface, surfacing only during storms or when angered by human disturbances.

In Luo and neighboring cultures, the Ogogo is often linked to stories of disappearances at lakes and floods that destroy settlements. It represents the unpredictable power of water — not simply a monster, but a guardian of sacred or dangerous places. Elders say the Ogogo can overturn boats, drag swimmers to the depths, or appear in dreams to warn of ecological imbalance. Fishermen traditionally offered libations or prayers before entering waters rumored to be Ogogo territory, acknowledging the being’s presence and asking permission to cross.

Like many African water spirits, the Ogogo exists at the intersection of metaphor and observation: fierce animals like hippos, crocodiles, or leopards near rivers likely influenced the being’s characteristics. But the emphasis on glowing eyes, storms, and supernatural agency suggests a deeper symbolism — the recognition that water is both life-giving and deadly, and must be approached with respect. The Ogogo endures as a reminder that hidden forces dwell beneath still waters.

Popobawa

Region: Africa

Location:Tanzania, especially Zanzibar (Pemba Island), with reports across the Swahili Coast

Popobawa is one of East Africa’s most infamous modern folkloric beings — a shape-shifting, bat-like entity associated with night attacks, sleep paralysis, and periods of mass fear. The name derives from *popo* (bat) and *bawa* (wing), reflecting the creature’s most common form: a large humanoid shadow with massive bat wings and glowing red or yellow eyes. Popobawa is said to appear in bedrooms or huts at night, pressing on sleepers, whispering threats, or physically assaulting them before vanishing. It moves as smoke, shadow, or an invisible presence, and many accounts describe its arrival by the strong smell of sulfur or a sudden change in air pressure.

Unlike most cryptids, Popobawa legends erupted in waves — documented public panics in 1972, 1995, 2000, and later. These waves often followed political unrest, social upheaval, or natural disasters, leading researchers to interpret Popobawa as a cultural expression of stress, trauma, and shifting identity along the Swahili coast. Traditional Swahili beliefs include spirits (*djinn*, *majini*, *mashetani*) that interact with humans, and Popobawa is sometimes framed as a powerful jinni bound or released through sorcery. Its attacks are said to be both psychological and physical, blurring the line between nightmare and spiritual fear.

Villagers historically countered Popobawa’s visits by sleeping outside in groups, staying awake, or using ritual protections performed by mganga (healers) who invoked Qur’anic verses or Swahili charm traditions. One consistent trait across accounts is that Popobawa demands to be spoken about — those who deny its existence are said to be targeted first. This strange detail made the fear self-reinforcing: silence invited danger, so entire communities narrated the legend together, keeping its power alive.

Location:Tanzania, especially Zanzibar (Pemba Island), with reports across the Swahili Coast

Popobawa is one of East Africa’s most infamous modern folkloric beings — a shape-shifting, bat-like entity associated with night attacks, sleep paralysis, and periods of mass fear. The name derives from *popo* (bat) and *bawa* (wing), reflecting the creature’s most common form: a large humanoid shadow with massive bat wings and glowing red or yellow eyes. Popobawa is said to appear in bedrooms or huts at night, pressing on sleepers, whispering threats, or physically assaulting them before vanishing. It moves as smoke, shadow, or an invisible presence, and many accounts describe its arrival by the strong smell of sulfur or a sudden change in air pressure.

Unlike most cryptids, Popobawa legends erupted in waves — documented public panics in 1972, 1995, 2000, and later. These waves often followed political unrest, social upheaval, or natural disasters, leading researchers to interpret Popobawa as a cultural expression of stress, trauma, and shifting identity along the Swahili coast. Traditional Swahili beliefs include spirits (*djinn*, *majini*, *mashetani*) that interact with humans, and Popobawa is sometimes framed as a powerful jinni bound or released through sorcery. Its attacks are said to be both psychological and physical, blurring the line between nightmare and spiritual fear.

Villagers historically countered Popobawa’s visits by sleeping outside in groups, staying awake, or using ritual protections performed by mganga (healers) who invoked Qur’anic verses or Swahili charm traditions. One consistent trait across accounts is that Popobawa demands to be spoken about — those who deny its existence are said to be targeted first. This strange detail made the fear self-reinforcing: silence invited danger, so entire communities narrated the legend together, keeping its power alive.

Sasabonsam

Region: Africa

Location:Ashanti (Akan regions of Ghana)

Sasabonsam is a fearsome forest being from Ashanti folklore, described as a tall, red-skinned humanoid with long, rope-like hair and legs that end in iron hooks instead of feet. He lives high in the canopy of deep forests, waiting for hunters or travelers who pass beneath. Some stories say he dangles his long legs down like vines, catching people as they walk by. Other accounts describe him swooping down like a monstrous bat. His iron-hook legs are sometimes said to clang against branches as he moves — a sound that warns attentive travelers.

Unlike many Akan spirits who can be bargained with or appeased, Sasabonsam is almost always predatory. The forests where he resides are described as “unreturning places,” emphasizing both physical danger and spiritual taboo. The creature represents the fear of becoming lost or taken by the deep wilderness — an embodiment of the danger that lies beyond cultivated, communal land. Hunters tell stories of spotting shapes in treetops or hearing the metallic scraping of hooks on bark, interpreting these as signs of Sasabonsam’s presence.

In Ashanti cosmology, Sasabonsam exists alongside the Asanbosam — a slightly different but related being who also dwells in trees. Oral tradition often blurs the two, but Sasabonsam is typically the larger and more menacing version. The being reinforces the need for ritual preparation before entering the forest, respect for sacred groves, and caution during hunts. In many ways, Sasabonsam symbolizes both the literal and spiritual dangers of the untamed forest — a place where the boundary between the human world and the hidden one becomes perilously thin.

Location:Ashanti (Akan regions of Ghana)

Sasabonsam is a fearsome forest being from Ashanti folklore, described as a tall, red-skinned humanoid with long, rope-like hair and legs that end in iron hooks instead of feet. He lives high in the canopy of deep forests, waiting for hunters or travelers who pass beneath. Some stories say he dangles his long legs down like vines, catching people as they walk by. Other accounts describe him swooping down like a monstrous bat. His iron-hook legs are sometimes said to clang against branches as he moves — a sound that warns attentive travelers.

Unlike many Akan spirits who can be bargained with or appeased, Sasabonsam is almost always predatory. The forests where he resides are described as “unreturning places,” emphasizing both physical danger and spiritual taboo. The creature represents the fear of becoming lost or taken by the deep wilderness — an embodiment of the danger that lies beyond cultivated, communal land. Hunters tell stories of spotting shapes in treetops or hearing the metallic scraping of hooks on bark, interpreting these as signs of Sasabonsam’s presence.

In Ashanti cosmology, Sasabonsam exists alongside the Asanbosam — a slightly different but related being who also dwells in trees. Oral tradition often blurs the two, but Sasabonsam is typically the larger and more menacing version. The being reinforces the need for ritual preparation before entering the forest, respect for sacred groves, and caution during hunts. In many ways, Sasabonsam symbolizes both the literal and spiritual dangers of the untamed forest — a place where the boundary between the human world and the hidden one becomes perilously thin.

Tokoloshe

Region: Africa

Location:Primarily Zulu and Xhosa regions (South Africa), but known widely across southern Africa

The Tokoloshe is a small, mischievous, and often malevolent spirit in Southern African folklore. Descriptions vary by region, but it is typically portrayed as a dwarf-like being with shaggy hair, elongated limbs, and sometimes missing features or sunken eyes. Some accounts describe it with a gremlin-like appearance; others say it can become invisible or only visible to those it targets. The Tokoloshe is associated with night terrors, household disturbances, and unexplained illness. Its presence is feared enough that many rural homes traditionally raise their beds on bricks — Tokoloshe is said to attack sleepers who rest too close to the ground.

Folklore says Tokoloshe may be summoned by individuals seeking revenge, jealousy, or mischief. A jealous neighbor or rival might call upon a Tokoloshe to harass a household — knocking things over, causing nightmares, or in more sinister tales, smothering sleepers. Traditional healers known as *sangomas* are called to remove or repel the spirit. They perform cleansing rituals, burn protective herbs, or communicate with ancestors to restore balance. These rituals highlight how the Tokoloshe is woven into broader spiritual and moral systems, not just fear.

Despite its fearsome reputation, some stories portray Tokoloshe with humor — playing pranks, stealing food, or mimicking voices. Many elders note that Tokoloshe stories historically reinforced social boundaries: warnings to avoid sleeping alone, to keep homes protected, or to discourage feuds between neighbors that might escalate into spiritual retaliation. In modern South Africa, Tokoloshe remains one of the most iconic supernatural beings — equally feared, joked about, and woven into everyday talk.

Location:Primarily Zulu and Xhosa regions (South Africa), but known widely across southern Africa

The Tokoloshe is a small, mischievous, and often malevolent spirit in Southern African folklore. Descriptions vary by region, but it is typically portrayed as a dwarf-like being with shaggy hair, elongated limbs, and sometimes missing features or sunken eyes. Some accounts describe it with a gremlin-like appearance; others say it can become invisible or only visible to those it targets. The Tokoloshe is associated with night terrors, household disturbances, and unexplained illness. Its presence is feared enough that many rural homes traditionally raise their beds on bricks — Tokoloshe is said to attack sleepers who rest too close to the ground.

Folklore says Tokoloshe may be summoned by individuals seeking revenge, jealousy, or mischief. A jealous neighbor or rival might call upon a Tokoloshe to harass a household — knocking things over, causing nightmares, or in more sinister tales, smothering sleepers. Traditional healers known as *sangomas* are called to remove or repel the spirit. They perform cleansing rituals, burn protective herbs, or communicate with ancestors to restore balance. These rituals highlight how the Tokoloshe is woven into broader spiritual and moral systems, not just fear.

Despite its fearsome reputation, some stories portray Tokoloshe with humor — playing pranks, stealing food, or mimicking voices. Many elders note that Tokoloshe stories historically reinforced social boundaries: warnings to avoid sleeping alone, to keep homes protected, or to discourage feuds between neighbors that might escalate into spiritual retaliation. In modern South Africa, Tokoloshe remains one of the most iconic supernatural beings — equally feared, joked about, and woven into everyday talk.

Comments