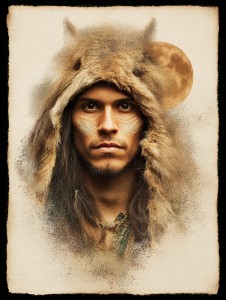

Cahokia Animist

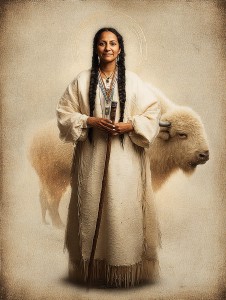

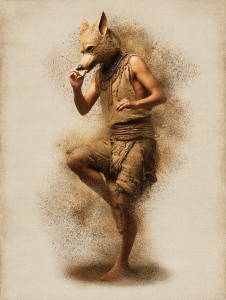

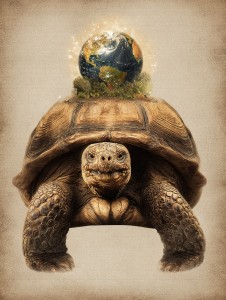

Cahokian animist traditions are animistic and polytheistic — meaning they revere spirits in all living beings and natural forces, while also venerating multiple deities, cultural heroes, and ancestors. Animism here signifies that mountains, rivers, animals, and winds are alive and sacred. Polytheism refers to gods and spirits like the Great Spirit, Thunderbird, Corn Mother, and trickster figures such as Coyote or Raven, each embodying vital cosmic forces.

Origins & Historical Development

In our history, colonization fractured and erased many Indigenous traditions. In Koina’s divergence, with no European conquest, the spiritualities of Cahokia continue unbroken, thriving in confederations and tribal federations across the continent. Plains nations, woodland confederacies, and desert peoples all preserve and adapt their traditions within federative governance. Without suppression, sacred ceremonies — Sun Dance, Green Corn festivals, potlatches — evolve openly into civic and ecological celebrations, recognized within the Accord.

Core Beliefs & Practices

These traditions emphasize harmony with land, reciprocity with spirits, and continuity with ancestors. The Great Spirit is often seen as a pervasive cosmic presence, while countless other spirits embody animals, plants, or natural features. Rituals include seasonal dances, sweat lodges, vision quests, and ceremonies of offering. Storytelling transmits moral and cosmological knowledge, with trickster tales teaching humility, humor, and resilience. In Koina, these practices become both spiritual and civic, guiding ecological management and communal identity.

Sacred Texts & Traditions

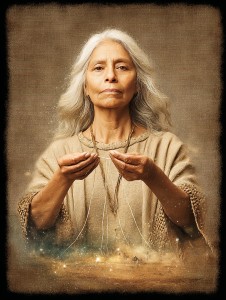

Cahokian animist traditions are primarily oral, carried in myths, songs, and ceremonies. Myths explain creation, migration, and the cycles of nature — such as Sky Woman’s descent, Raven bringing light, or Coyote’s tricks. In Koina, these oral traditions are carefully recorded into the Net of Voices, but performance remains sacred: stories must be told, sung, and danced to retain power. Ritual objects — masks, drums, bundles — embody living presence, not mere symbolism.

Institutions & Structure

Spiritual authority rests with shamans, medicine people, and elders, who mediate between communities and the spirit world. Councils of elders oversee ceremonies and seasonal gatherings. In Koina, tribal federations incorporate medicine guilds and elder councils into civic assemblies, ensuring continuity of ecological stewardship and ritual governance. Sacred sites — mountains, rivers, burial grounds — are protected by federative law, recognized as commons of both spiritual and ecological significance.

Relation to the Accord

Cahokian traditions contribute to the Accord through their ecological and communal ethos. Their emphasis on reciprocity with land informs federative treaties on forests, plains, and rivers. Ceremonies of renewal and thanksgiving become global civic holidays, celebrated across federations. Their philosophy of kinship — where animals and humans are relatives — strengthens Accord ethics of ecological stewardship and restorative justice.

Cultural Influence & Legacy

Art — totems, beadwork, quillwork, and painted hides — enrich Koina’s cultural fabric. Music, drumming, and communal dances shape cooperative festivals. Trickster tales influence theater and literature, their humor and paradox resonating across federations. Ethically, Indigenous teachings of balance, respect, and reciprocity add to the plural moral vocabulary of the Cooperative Federation.

Modern Presence

Today, Cahokian animist traditions thrive in confederations from the Iroquois to the Lakota, Navajo, and Coast Salish. Seasonal gatherings such as powwows, Sun Dances, and Green Corn festivals remain central civic events. Indigenous languages, myths, and rituals are preserved not only locally but in the global Net of Voices. Far from being marginalized, these traditions are recognized as living, guiding paths — teaching that the earth itself is kin, and that human life is sustained only through reciprocity with the wider web of beings.

Type

Religious, Organised Religion

Alternative Names

First Nations Spiritualities; Ways of the Spirits

Demonym

First Nations / Indigenous Peoples

Controlled Territories

Afterlife

Animist Afterlife

The just return to the Spirit Lodge or the Land Beyond the Sky, where ancestors and totems gather in continual celebration. They dance the eternal circle of creation, guiding the living through dream and wind.

Comments