Akan (AH-kahn)

Akan religion is a polytheistic and ancestral tradition — meaning it venerates a supreme sky deity (Nyame) alongside many abosom (deities) of rivers, forests, and community, while honoring ancestors as active guardians of the living. Polytheism here refers to devotion to multiple abosom, each linked to a natural or moral domain. Ancestral veneration recognizes that departed kin continue to guide and protect families and villages through ritual memory.

Origins & Historical Development

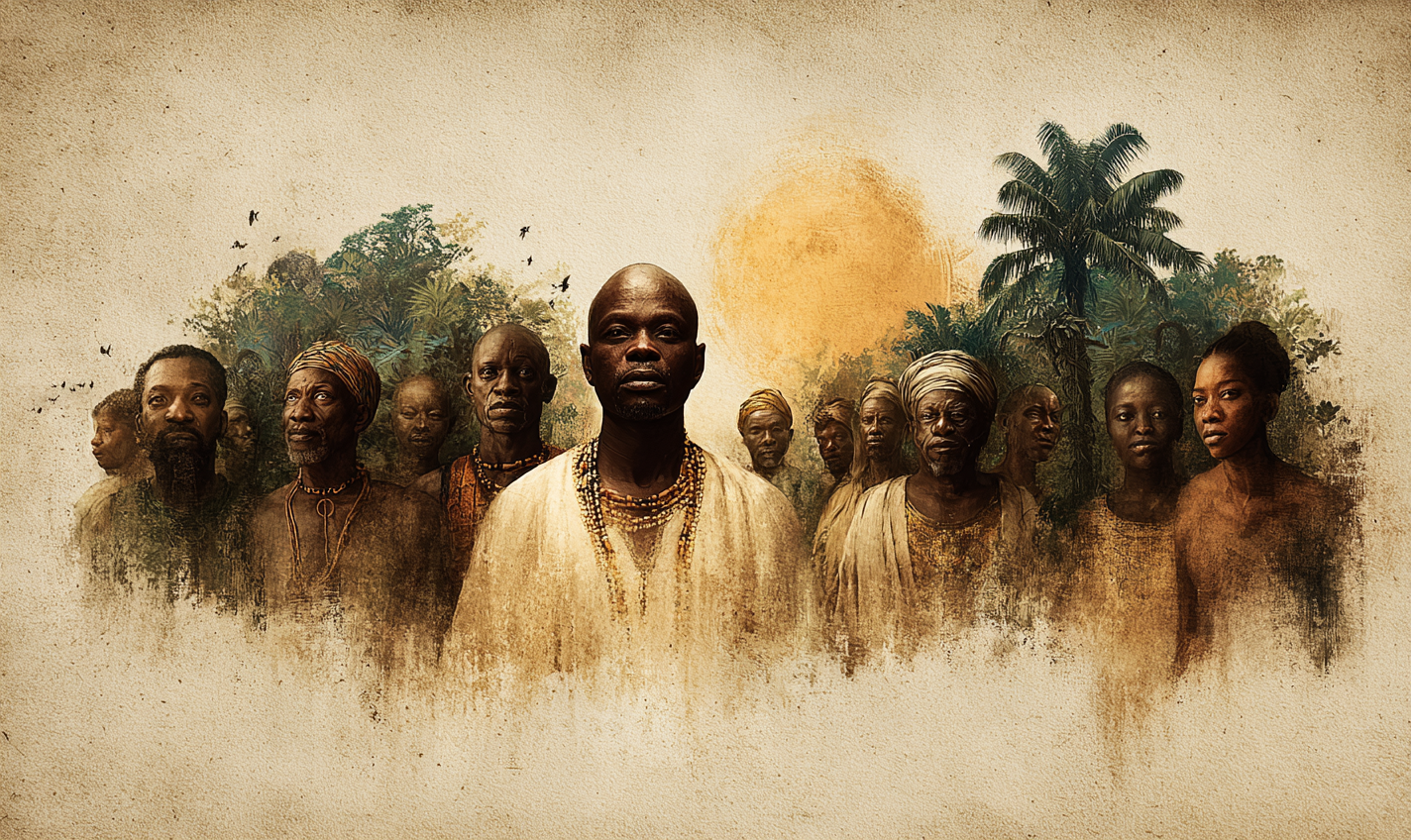

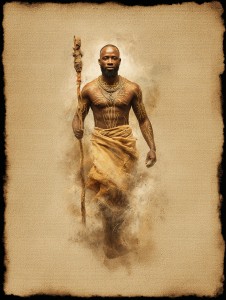

The Akan religion develops among the Akan peoples of present-day Ghana and Ivory Coast. In our history, colonialism and missionary activity displaced it; in Koina’s divergence, without European conquest, Akan spirituality remains continuous and thriving. Akan federations incorporate priestly guilds into their civic assemblies, ensuring abosom shrines and ancestral rituals remain central to community identity. Over centuries, Akan merchants and travelers carry their faith across West Africa and into the wider Cooperative Federation.

Core Beliefs & Practices

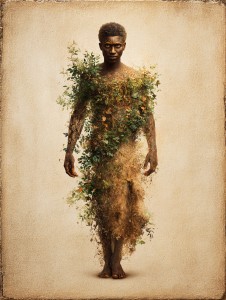

At its heart is Nyame, the supreme creator, who delegates authority to abosom — deities of rivers, earth, fertility, and justice. Among these are Asase Yaa (Earth Mother), Tano (river spirit), and Bosomtwe (sacred lake spirit). Ancestors (Nsamanfo) are honored in libations, sacrifices, and annual festivals, ensuring continuity of kinship. Rituals include drumming, dance, possession ceremonies, and offerings at shrines. Ethical life emphasizes reciprocity, respect for elders, and alignment with communal harmony.

Sacred Texts & Traditions

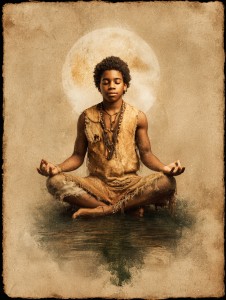

The Akan religion is oral, preserved through proverbs, stories, and ritual chants. Priests and elders maintain genealogies and mythic cycles, which in Koina are transcribed into the Net of Voices for preservation and cross-cultural dialogue. Proverbs, in particular, serve as vehicles of wisdom — short sayings that encapsulate moral lessons, often cited in federative assemblies to resolve disputes.

Institutions & Structure

Religious authority rests with priests and priestesses (akomfo), who serve as mediums for the abosom. Shrines and sacred groves are maintained in every village, often doubling as community courts and meeting places. Chiefs and elders are recognized as both political and spiritual figures, bound to uphold tradition and maintain harmony. In Koina, priestly guilds of the Akan contribute to regional assemblies, with diviners and mediums serving as Whispers in councils.

Relation to the Accord

The Akan religion enriches the Accord through its deep integration of ecology, kinship, and law. Sacred groves and rivers influence federative environmental treaties, while ancestral veneration reinforces Accord commitments to genealogy and memory. Akan festivals — such as Odwira (purification) and Akwasidae (ancestor remembrance) — attract pilgrims from beyond West Africa, turning local traditions into global civic events.

Cultural Influence & Legacy

Akan art — goldweights, kente cloth, and symbolic adinkra designs — spreads widely across Koina. Adinkra symbols, representing virtues like strength, wisdom, and unity, become popular emblems across federations. Music and drumming patterns shape global rhythms, while storytelling traditions influence theater and education. Philosophically, the Akan emphasis on communal balance and respect for elders becomes part of Accord political discourse.

Modern Presence

By modern day, Akan religion thrives in Ghana, Ivory Coast, and diaspora communities across Africa and the western continents. Shrines, groves, and festivals remain central to community life. Chiefs and priestly leaders continue to mediate between tradition and modernity, while Akan symbolism is visible in art, clothing, and public life across federations. Far from being a suppressed tradition, the Akan religion stands as a continuous, living faith — one that embodies the Cooperative Federation’s ethos of kinship, reciprocity, and balance with nature.

Type

Religious, Organised Religion

Alternative Names

Akan Spirituality; Faith of Nyame

Demonym

Akan

Related Myths

Afterlife

Akan Afterlife

In Akan thought, the soul’s fulfillment is a peaceful return to Asamando, the realm of the honored ancestors. There, spirits dwell among family lineages, guiding their descendants through dreams and omens. The living pour libations and call the names of the dead, keeping the chain of memory unbroken.

Akan Afterlife

Those who live selfishly or betray communal harmony are denied that welcome. Their spirits become sunsum mu ye fɔ — restless shades wandering between worlds. They linger on the edges of villages or forests, unseen but felt, yearning for the rites that would restore them to their people’s embrace.

Comments