Ýïrúl War

The Ýïrúl War, or the Ýïr-Úl War (the Five-Tribe War), was one of the very first subconflicts in the Khólteðian Wars and among the most volatile. It involved five tribes: Ërëšð-Ýïr, Këhóš-Ýïr, Ýbašý-Ýïr, Rlúýš-Ýïr, and Šïbha-Ýïr, and was mainly located in the land at or near the confluence of the five tribes' borders. Due to the ferocity of the conflict, and the effects it had on the participants, the Ýïrúl War would become the catalyst for other subconflicts like the Këhóš-Belúb War.

Prelude

A Brief Summary of the Crisis of 24982 AYM

The tribes that made up the Khólteð Tribe (the short-lived interim organization led by Šïk-hórom) were not created during the settlement period but instead during the Crisis of 24982 AYM, that is, the prelude to the Khólteðian Wars and one of the deadliest conflicts in its own right. This Crisis occurred in the Ïlýrhonid Tribe and marked the near-total collapse of the Khólteð Family as a functioning organization.

Due to their relevance to the complexities of the Ýïrúl War, the motives and happenings of the Crisis will be briefly summarized here.

The Events Leading up to the Crisis

The Crisis came about due to the actions of the Khólteðtian Öhr-Fëkahr, who broke with established tribal conventions and committed Ýyorhïsïb with members of other families. The resultant population descending from him and his actions was quickly labeled the Fýr-Hŋýtor, and confined to designated spaces known as the Krëšŋ-Ðórr and Khëlër-Ðórr. This population quickly grew, and by 25015 AYM they represented around 10% of the family's population. Around that time, they rallied around Žúž-Akëð, who called for the creation of a Hŋýtian army to combat the ostracization they suffered. This included the renaming of their organization, especially those who followed this millitant approach, to the Arðor-Tal. Over time, the aims of this group would transition to one more focused on the disestablishment of the familial authority (the Hyvamto-Žö-Ýšïb).

The Early Events of the Crisis

In 24982 AYM, Týyšat, the Hyvamto-Žö-Ýšïb, died, with Šïk-hórom due to succeed him. Mere hours before he was to ascend to the role, members of the Arðor-Tal kidnapped Šïk-hórom, prompting the creation of the Arðor-Úŋï, that is, those siding with Šïk-hórom and the Hyvamto-Žö-Ýšïb in general. Note that both the Talians and Úŋïans spent the vast majority of their existence in the Crisis as wholly united organizations. At first, this conflict was confined to the Krëšŋ-Ðórr, the location where the Talians were holding Šïk-hórom, but the escalation of the conflict, especially after the Massacre of the Krëšŋ-Ðórr, resulted in public pandemonium. This would usher in the Kýïan Wars, the series of chaotic infighting that filled the streets of the Family. This infighting was mainly the result of what are called the Arðor-Kýï, a posthumously-defined category of tribes that were not united, but merely sought to take advantage of the power vacuum that had emerged to exact personal gains or to carry out a goal that did not align with either the Talians or the Úŋïans. As the conflict spread through the Family, more of these Kýïan Tribes would be created in waves; while the first wave of Kýïan tribes was mainly concentrated in the central-southwestern region of the familial land (near the massacre and the Battle of Arhžvóo), the movement of both the Kýïan and Tal-Úŋï conflicts northeastwards would result in a second-wave cluster of Kýïan tribes emerging at that location. While the first wave was mainly concerned about feuds and street fighting, the second wave consisted of organized attempts to seize the palace, or Ëzó-Rhažóval, of the Family.

Later Events in the Kýïan Wars, and the Creation of the Five Ýïrúlian Tribes

Near the end of the first phase of the Kýïan Wars, the tribe of Këhóš-Ýïr would be formed, most likely trying to take advantage of the chaos of the first phase, both to battle towards a potential takeover of the Ëzó-Rhažóval and to prevent those of the First Phase tribes from doing so as well. In contrast, the latter second-wave group of tribes included Ërëšð-Ýïr, another of the five tribes in the Ýïrúl War, which was made of various defecting elements of the Khólteð Family's army who aimed to take power from Ïlðúš-Ýïr, the then-interim government established by the Úŋïans. It is yet unclear what the exact intentions of the Ërëšð-Ýïr, but they were entirely and fundamentally different in ideology from the Ïlðúš-Ýïr, and engaged in the most brutal fighting with this interim government. Among those supporting Ïlðúš-Ýïr was the tribe of Rlúýš-Ýïr, who fought ferociously against both the Kýïans and the Talians throughout the Crisis.

The broader conflict quickly changed due to the ferocity and brevity of the following events, namely the Battle at the Palace in 19-22 Ulta-Eimarae and the subsequent Ceasefire of Zïlëŋý in 25 Ulta-Eimarae. This ceasefire, created by the Hyvamto-Rhïlýrhonid Zümiža, specifically attempted to restore lasting peace through the separate representation of the Talians and Úŋïans. Among this was the relocation of these two groups, inhabiting two wedge-like areas designed to each be half that of a regular family. Most crucially, however, the lack of representation given to the Kýïans, and the impossibility of this representation given the sheer complexity, resulted in the dissolution of the ceasefire around 3 Suta-Eimarae and the reemergence of small-scale skirmishes between all three sides. With the relocation of the Talians and Úŋïans, and continued assaults from the Kýïans, many of the internal fractures in the Arðor-Tal and Arðor-Úŋï occurred due simply to organizational stress and strain. Ýbašý-Ýïr, a prominent example of this fracture, was independently proclaimed by three warlords (Kóvað, Šófëð, and Ðúrýlór) united in brotherhood with each other and with their armies. Similarly, the tribe of Šïbha-Ýïr was formed out of a division within the army that had been separated and cut down during the Massacre; their extreme beliefs and goals, strongly affected by what they had experienced, put even the rest of Arðor-Tal at odds with them. By the end, there had been are 32 separate tribes, or Ýïr, each of whom had to face threats from at least five other tribes at once.

End of the Crisis, Expulsion from the Tribe, and Resettlement in the Tayzem Region

The period of instability and renewed violence came to a head in the Battle of Köš-Ëmvrad in 13-16 Geta-Eimarae. The sheer magnitude thereof finally forced Zümiža to enact the 24982 AYM Ultimatum in 15 Geta-Eimarae, formally expelling the entirety of the Khólteð Family from the Tribe. In a last-ditch attempt to ensure continued peace in the family, the Ultimatum included within itself several rules, all of whom were, to some degree, agreed to by all 32 tribes.

- Šïk-hórom was to be reinstated as the Hyvamto-Žö-Ýšïb, albeit with severe limits on power

- All tribes were to remain intact as befit the will of the constituent individuals; the government could not force a tribe to dissolve

- The Family would be given until 5 Heta-Eimarae, 24980 AYM, to collect their belongings and leave. Throughout this time, all hostilities were to cease, and safe travel throughout all territories within the Familial land was to be enforced. This entire process would be closely monitored by armies from various portions of the tribe's army.

The Family was dilligent in these regards, leaving by boat on 3 Heta-Eimarae. From there, they would sail southwards, into the Ëriðorn Ocean. The wind and the waves would guide them westwards to the Tayzem Desert, on whose eastern coast the first ships (comprising Šïk-hórom, his family, and members of his army) would land on 10 Heta-Eimarae.

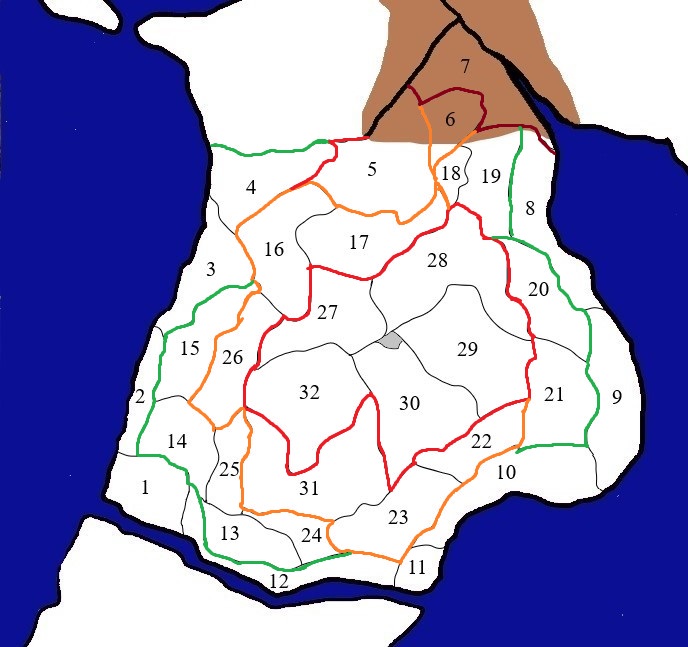

This above image shows the territories of the 32 Tribes of the Khólteð Family before the outset of the Khólteðian Wars. The color-coded lines represent the layers of cliffs that defined the geography; redder lines denote a higher altitude, while green denotes a much lower one. This does NOT include minor cliffs, only those with enough height in themselves to hinder travel by a significant margin.

Geography of the Tayzem Desert

Throughout the latter half of Heta-Eimarae, a thorough exploration of the entire Desert was carried out. Because the tribal boundaries were so dependent on the geography of this region, a short overview will be given here.

The Tayzem Desert is one of two major examples (alongside the Yožýr-Hbüš) of what is called a ribbed desert. Here, large expanses of rock are so close to the coastline that the effects of the wind create massive cliffs. Unlike the Yožýr-Hbüš, whose rock has special glass-like filament that forms a building block for new cliffs, it is thought that the Desert was originally a massive stratovolcano that has since been leveled by erosion. Instead of being hit head-on by the wind, the rock is scraped from the side, effectively shearing off a bit at a time for each gust. As one goes higher in altitude, the winds grow dramatically stronger and larger from height zone to height zone.

Because of the sheer amounts of exposure that the Desert is subject to (from the Merios Lake in the northwest, Tlïvhakk Ocean to the west, the Ŋaraïðúl Strait to the south, and the Tžamókk Bay/Ëriðorn Ocean to the east), this creates a series of winds that create a wedding-cake-like configuration; each altitude zone, with its own system of winds, batters the rock from all directions and altogether, they sculpt a roughly-circular platform into the rock, on which rests the platform of the altitude zone above it. To reduce difficulties in travel, the boundaries between tribes were partly determined by these cliffs.

The placement of tribes throughout the region was equally political as it was geographical. To reward those who fought valiantly on the side of the Hyvamto-Žö-Ýšïb, Šïk-hórom had it such that these tribes were given land bordering the waters, where sustainable farming could be done; this was a huge advantage over landlocked tribes, who had to depend on the destructive and nonreplenishable practice of mining. Such a blessing befell tribes like Këhóš-Ýïr and Ërëšð-Ýïr, with the rest being given land pertaining to the cliffs above the coastal regions.

Tribe-Specific Geographies

The five tribes of the Ýïrúl War were concentrated at the southwestern corner of the Tayzem Region. By 1 Nota-Eimarae, all of them and their respective populations had fully settled in these areas.

Këhóš-Ýïr (1)

Main Article: Këhóš-Ýïr

As a preliminary exploration of the societal and geosocial situation, the various cliffside cities of the Këhóš-Ýïr will be listed and explained. Këhóš-Ýïr's large cliff was, like all natural formations, extremely jagged and prone to small variations in shape and size. Regarding the preeminent cliffside, it was not a singular wall, but a collection of miniature cliffs that coexisted and sometimes built upon one another in height. In this sense, it represented an irregular set of stairs, and this would be used by the Këhóšians to travel up and down the cliffs as they pleased. Across the entire expanse that was the Këhóšians' territory, there would be at least 8 sets of these 'stairs', all used extensively during and after the conflict.

Due to the thin area of the coast, overpopulation, and other factors, towns had to be built above the cliffs, and owing to a desire for efficiency and a minimization of distances, these cities were constructed at the cliff edge and at the many mini steps that dotted the landscape. One of the most populous communities was established early on as the city of Kúr-Ïšš (Cauriss), located at the extreme southwestern corner of the tribe. This was between where the Tlïvhakk Ocean to the west entered the Ŋaraïðúl Strait to the south, and so the diverse water types and optimal coastline provided an integral source for farmland. Soon, the settlements would steadily creep up the cliff, materializing as the cities of Kúr-Ïžït, Kúr-Ölhórr, Ýðö-Mýs, and Ýðö-Mahïŋ. All of these were under the Ïšš-Ðahŋú, or the Kúr-Ïšš area. While the latter two were situated at the very top of the cliff (hence their common prefix), the others with the Kúr- prefix were situated on the intermediate clfifs or outgrowths, those being the 'steps' of the cliffs as discussed above. Kúr-Ïžït, the location of this specific battle, is unique in that it was not located within the series of intermediate steps but was on a singular, isolated ledge away from the rest of the cities.

Këhóš-Ýïr had two other major urban areas, Öšërk-Ðahŋú and Vakýë-Ðahŋú, that were also located at the coast some kilometers to the north of the Ïšš-Ðahŋú. These three areas thus split the coastline into a north, a central, and a south region, each of which experienced heavy amounts of farming. However, due to the Ïšš-Ðahŋú's easy access to plentiful nutrients (due to the change in the body of water and thus the nutrients that could be found), it was by far the most populated, and thus became the hub from which the tribe's most substantive efforts towards government (Khlúkúrmïr) and military (the Ëŋšïk system) first arose.

Ýbašý-Ýïr (14)

Main Article: Ýbašý-Ýïr

Ýbašý-Ýïr occupied a piece of land above the first set of inland cliffs, thus providing for itself an overhead view of lower tribes like Këhóš-Ýïr and Belúb-Ýïr. While the inland tribes had to dig into their own land for food and construction, dealing permanent structural damage and possibly incurring rockslides, the coastline folk had access to the nutrient-rich ocean, from which they could grow hoards and hoards of food without any noticeable damage to the environment. Fueled by jealousy, and a need for a more stable source of sustenance, it would use this vantage point to plan large-scale raids on these tribes, with the rationale that enough raids would cause them to bow to the Ýbašïans and force them to pay tribute harvests to them.

Rlúýš-Ýïr (25)

Main Article: Rlúýš-Ýïr

Rlúýš-Ýïr was one of the Arðor-Úŋï, and the only such Úŋïan tribe to participate in the Ýïrúl War. Of the 32 tribes, it is one of the most obscure in terms of its mission and ideologies, primarily because it is thought to have abandoned its original values developed in the Crisis in favor of a purely survivalistic mentality when they resettled in the Tayzem Desert. They were led by Rïhý-Úšöl, who died sometime within the Crisis, and then by Müžrónð, the brother of the Këhóšïan Müžúökrš, who led them in their ultimately victorious campaigns of the Ýïrúl War.

The Rlúýšians were assisted by the fact that they resided on relatively elevated land compared to the other 4 tribes. This increase in elevation is not marked in the map above, as this increase only measured at around 15 meters above the layer beneath it and the map only marks out the most dramatic altitude changes (that is, those corresponding to the different layers of wind), which only really created cliffs of height 50 meters or more. It is often said that this 15 meter difference alone was the deciding factor behind the fates of all five tribes, and by extension the majority of the other tribes in the Khólteðian Wars.

Šïbha-Ýïr (13)

Main Article: Šïbha-Ýïr

The Talian tribe of Šïbha-Ýïr holds a tremendous role in the Crisis due to its position as one of the two most populous splinter tribes of the once-unified Talian front. It was comprised of most (~80%) of the survivors of the battered Talian army, which after the Battle at the Palace numbered only at around 1,500. Alongside the civilian-composed sister tribe of Šïvýð-Ýïr, Šïbha-Ýïr was one of the two foremost representatives of the Talian cause when deliberations regarding the Ceasefire of Zïlëŋý were carried out, and it is largely due to these deliberations that the Talians were given representation within Ïlýrhonidian tribal politics equal to a full half of a regular family. However, the Šïbhians were often perceived as neglecting the viewpoints and needs of other splinter Talian tribes, and in 27 Anta-Eimarae, the Šïbhian leader Ëšrum-Ðofek was assassinated by members of Múuŋ-Ýïr, and their leader Sðó-šöŋ became the de facto representative of the Talians.

Following their toppling, the Šïbhians, regrouped under Ýžram-Ŋóðar, became a prominent military unit in Talian defenses, serving in numerous skirmishes that occurred between the Talians, Kýïans, and Úŋïans. These would whittle the population down to around 900, but render them among the most battle-hardened and weathered individuals in the entire Khólteð Family.

In the Ýïrúl War, the Šïbhians endured considerable turmoil, as the majority of the second phase occurred in their own territory, with the Šïbhians being forced to exact selective defenses of their own towns. Similarly, they would play a significant role in the successive conflict known as the Ašðïan War, in which the two main warring groups, the tribes of Hfašð-Ýïr and Ašëð-Ýïr, were situated on either side of the Šïbhian territory. By the end of that second conflict, the Šïbhian lands were so ravaged by war that their cliffs had collapsed and their surviving populace were forced to migrate westwards as a nomadic group.

Ërëšð-Ýïr (12)

Main Article: Ërëšð-Ýïr

The Ërëšðians are akin to the Šïbhians in regards to their military nature, as noted by their highly-distinctive 'šð' phoneme. However, Ërëšð-Ýïr's ties to the military do not mainly arise from the Crisis itself, but from the army of the Khólteð Family that was raised during the First Ýlëntukian War of 25020-25003 AYM. Although it was never used, this familial army became exemplary for its extensive discipline (due to the responsibility of having to protect such a large family), and when the army disbanded in 24990 AYM, its members largely held to the values that were instilled in them. These members of the army would go on to be the dominant group within two Kýïan tribes, Ërëšð-Ýïr and Ašëð-Ýïr, with the former comprising those that were older and the latter comprising those that were younger. However, for the majority of the Crisis, these two tribes were not formed.

Being situated in the northeast of the familial lands, these army members were unaware of the existence of the Crisis until the Second Phase, when the Battle at the Palace finally saw the conflict break out of its confined spaces in the southwest. Following the deliberations of the Ceasefire, which saw Kýïan tribes and other parts of the populace that were not Talian or Úŋïan-aligned largely sidelined, both tribes would form in response. In fact, the Ërëšðians and Ašëðïans became among the most active in the early skirmishes after the Ceasefire, which ultimately led to the dissolution of the Ceasefire and around a month's worth of continued fighting before the final 24982 AYM Ultimatum in 15 Geta-Eimarae.

Due to their roles in reigniting the violence, the distribution of lands by Šïk-hórom and the Familial government saw both tribes rendered extremely vulnerable, and Ërëšð-Ýïr is perhaps the most blatant example of such a vulnerability. They were relegated to land that stretched nearly 300 kilometers in length but only measured around 15-100 meters wide (depending on the exact location). To the south, they were held back by the Ŋaraïðúl Strait, whose cliffs represented some of the highest vertical drops (around 300 meters at its highest). Although this extreme geographical weakness was exploited to its fullest by the Hfašðïans during the Ašðïan War, the Ýïrúl War itself did not see any of the other tribes make successful advances into Ërëšðïan territory, and the army itself mainly conducted advances in the lands of other tribes (although substantial units guarded the western and northern borders).

Rlúýš-Ýïr is úŋï

Conflict

Phase 1: Këhóš-Ýbašý War

The Ýïrúl War began at the border between the tribes of Këhóš-Ýïr and Ýbašý-Ýïr. This initial phase that only concerned these two tribes is called the Këhóš-Ýbašý War, and it was very much the formative period for both participants.

At that time, Këhóš-Ýïr was notably leaderless, with their leader being killed in the final days of the Crisis of 24982 AYM. Despite this, they were rewarded from their extensive service during the Crisis with a stretch of land on the coast, which they made use of for farming. Beyond this coastal region was a series of stepped cliffs that raised the height of the land to around 500 to 600 meters above sea level within the span of a few meters. With little internal coordination, they mainly preferred to stay in this coastal region, but isolated populations did exist on the cliffs and stretching throughout this above-ground region.

Ýbašý-Ýïr, on the other hand, was a thriving band of warriors led by three 'warlords': Šófëð, Ðúrýlór, and Kóvað, and it inhabited a territory of similar size to Këhóš-Ýïr. The border shared between these two tribes stretched from west to east, with the Ýbašý-Ýïr being the more northern tribe, and it would be the focus of extensive fighting during the entirety of the Ýïrúl War.

Ýbašïan Raids

The conflict between Këhóš-Ýïr and Ýbašý-Ýïr began with the raiding of small Këhóšian towns near the border; this was precipitated by the lack of workable land available to the latter, as by mid-Nota-Eimarae, they had already used up the vast majority of their land as food. What seemed especially desirable was the Këhóšians' access to the coast, which allowed for repeated farming of crops and thus the production of food without substantially damaging the land. However, they were hesitant, not knowing the situation of the Këhóšians and their army. As such, each raid was simultaneously done to gain additional land and to survey the strength of the Këhóšians. In this regard, they would resort to fear and intimidation tactics, including the ransacking of storehouses and, if necessary, physical injury, but given the sparseness of information regarding these early raids, these latter tactics were not used in abundance. Upon subjugation of a town, the Ýbašïans would quickly move on or retreat, intent on preserving their army in case the Këhóšians retaliated. Despite this, and because of the efficiency that coastal farming provided over inland mining, the majority of the Kheosian population was situated at the coast, and as such, this majority had little to no knowledge of the raids that were occurring.

From historical contexts, these raids took place from mid-Nota-Eimarae to early-to-mid Anta-Eimarae, 24981 AYM. Although all three warlords participated in these raids, Kóvað would carry out the bulk of them, especially during the late-Yota and Anta-Eimarae months. Together, these raids would reach the first of many cliffsides characteristic of the coastal regions; these cliffs towered around 500 meters above the beaches, which was were the majority of the Këhóšian towns were situated.

Note that, in addition to Këhóš-Ýïr, the Ýbašïans also raided the territory of their neighbor to the north, that is, Belúb-Ýïr, although their territory was much slimmer. Nonetheless, the raids on both tribes took up much of the warlords' time, contributing to the adoption of a convention whereby one warlord would raid in Këhóš-Ýïr, one warlord would raid in Belúb-Ýïr, and the third would stay in Ýbašý-Ýïr as the head of government.

Battle at Kúr-Ïžït

In 26 Anta-Eimarae, 24980 AYM, the Ýbašïans conducted another raid against the Këhóšians. By now, they had firmly occupied most of the small towns that were the targets of the previous raids, and in this towns they were conducting extensive mining. However, they still craved the self-sustenance of coastal farming, and in their jealousy, a 2,250 force led by Kóvað led the first of the offensives against the cities on the cliffs. This specific instance saw heavy fighting at and around the roughly-500-strong city of Kúr-Ïžït, resulting in the total collapse of the portion of the cliff the city was resting on. This sent members of both the city and the Ýbašïan army falling down into the coastal region directly, where they were then quickly surrounded by a crowd of Këhóšians. Sensing the situation growing out of control, Kóvað would send the remaining elements of his army in an attempt to descend via the cliff steps, break through the crowd, rescue the surrounded army members, and retreat back to Ýbašïan territory. Although successful, the high casualties sustained through all parts of the battle, which totaled 700-900, rendered Kóvað a deeply reckless commander in the eyes of his army and those of the other two warlords. For the Këhóšians, the majority of citizens of Kúr-Ïžït were killed, leaving only around 40-50 remaining. Most importantly, however, it finally alerted the Këhóšians to the presence of war, and forced them to take rapid action.

Creation of the Khlúkúrmïr and the Army of Këhóš-Ýïr

The Khlúkúrmïr, which means the guardian (Khlú-mïr) of the cliffs (Kúr) in Ïwë-Khólteð, was created in 27 Anta-Eimarae in response to the Battle of Kúr-Ïžït. The power of the Khlúkúrmïr was never really elaborated on during the history of the Këhóš-Ýïr, but was merely established through conventions established by the first Khlúkúrmïr, Hrülïšakr.

From 27 Anta-Eimarae to 10 Ulta-Eimarae, Hrülïšakr traveled across the entirety of the coastal towns. This included the Ïšš-Ðahŋú in the southwest, as well as two other densely-populated areas, namely Vakýë-Ðahŋú and Öšërk-Ðahŋú in the north and central regions of the coast. The route taken by Hrülïšakr became the main route connecting all three, something that had not existed before him. Hrülïšakr would also be the first to witness the destruction suffered by the towns targetted by the Ýbašïan raids, which sent shockwaves throughout the tribe when the news was brought back. Understanding the dire situation, he called for the creation of an army, made of citizens from all three areas in the coast, with the goal of taking back these towns, strengthening them, and conducting multiple offenses against the Ýbašïans themselves. By mid-Ulta-Eimarae, this army, called the Ëŋšïk, would number 3,500. For the time being, one-third of this army would be stationed in each Ðahŋú, each led by an individual called a Khlúðŋúmïr, with the purpose of staving off any future raids. In the meantime, Hrülïšakr would station himself in the middle city cluster of Öšërk-Ðahŋú, drawing up plans for future movements beyond the cliffs.

Ambush at Ïšš-Ënðó

Ïšš-Ënðó, or Asenthol, was one of the many towns far removed from the cliff edges, and thus a victim of the Ýbašïans raids that had plagued the region. It was also the nearest of these lone towns to the Ïšš-Ðahŋú in terms of location; estimates place its destruction at around 15 Anta-Eimarae. In 14 Ulta-Eimarae, it was sighted by Hrülïšakr as the first of a series of leapfrog maneuvers, with the endgoal of retaking the entirety of the Këhóšian lands. That day, him and 500 of his men trekked there, aiming to scout the condition of the city and from there, create a plan for the actual takeover. Within Ïšš-Ënðó itself, there were a number of scouts for the Ýbašïan army, numbering around 50-100, and upon seeing Hrülïšakr, they snuck out of the city and reported such to the warlords. Meanwhile, finding the city supposedly empty, Hrülïšakr returned back to the Ïšš-Ðahŋú and prepared to transfer that portion of his army (the Ïšš-Ëŋšïk) there.

As he was doing so, Sófëð would march to Ïšš-Ënðó with a large portion of his army (around 500) and command them to hide among the rubble. Now, at this time, the city of Ïšš-Ënðó had been relatively undeveloped, meaning that it lacked central structure. Instead, it had been a chaotic spattering of structures, which was rendered even more chaotic by the destruction suffered at the hands of the Ýbašïans. Due to the sheer numbers of the Ýbašïan army, they opted to reconstruct parts of buildings to provide additional means of hiding. This was only limited to specific walls and other small structures, but when the Këhóšian army returned to the site in 16 Ulta-Eimarae, these differences would be enough to render some individuals wary. Among these was Úrëŋod, the Khlúðŋúmïr of the Ïšš-Ëŋšïk, who, upon convincing Hrülïšakr of his worries, separated his army into two pieces; one of them was around a fourth of the total, and the other was three-fourths that of the total. Therefore, the Këhóšian army would circle the city multiple times, aiming for the clearest way into the middle of the city. This turned out to be a path originating at thenorthwestern edge of the city, and Úrëŋod had the lesser section of his army (around 250-300) rush through this path while the rest of them formed a dense ring around the entire city layout.

Upon rushing in, many of the Ýbašïans in hiding rose up to attack, believing this was the entire Këhóšian force. When the small Këhóšian force reached the middle of the city, they formed a tight group, and fought bitterly against the onslaught of the Ýbašïans. Meanwhile, the second group, was advancing in from all directions, and after an hour, the Ýbašïans would finally see the advancing forces and turn to flee. Sófëð himself would gather his forces to counterattack at a very specific point in the circle, effectively punching his way out and escaping the trap. Nonetheless, the chaos of the event still caused around 200 individuals within his army to die. Comparatively, the 250-300 who had initially rushed into the city suffered similar levels of casualties, with reports dictating around 150-200 of them being dead or severely maimed. Nonetheless, all of these survivors were granted full exemption from further military action, and returned to their hometowns as heroes.

Battle of Raðvïš-Ïmrú

Panicked by the defeat at Ïšš-Ënðó, Sófëð, Ðúrýlor and Kóvað would all decide to conduct a military offense en masse in Këhóš-Ýïr, both to secure their gains in that tribe and to quash any resistance within the populace. To secure their own territory, they would take with them every last member and disassemble all major structures, leaving the land completely barren and devoid of people. Kóvað, still aiming to redeem himself after the fiasco at Kúr-Ïžït, would place himself and his 2,500-strong army at the closest city to Ïšš-Ënðó, that being Vëlaš-Ïmrú. Sófëð, more cautious after his defeat, placed his 2,000-strong army just to the east of Kóvað's, with the intent of acting as a support if the engagement went sour. Ðúrýlor, in the meantime, would populate the abandoned city of Raðvïš-Ïmrú with his 4,000-strong army, which was situated far to the north of Ïšš-Ënðó, to capitalize on any gains the other two achieved.

Anticipating a response from Ýbašý-Ýïr, Hrülïšakr mobilized the other two armies, leaving the beleagured Ïšš-Ëŋšïk to rest at the Öšërk-Ðahŋú central area. However, knowing that the Ïšš-Ðahŋú were very limited in how well they could defend all three cities, he and the two armies with him conduct simultaneous and separate campaigns eastward; the Öšërk-Ëŋšïk led by Müžúökrš, would fight at the northern city of Raðvïš-Ïmrú and continue eastward from there, and the Vakýë-Ëŋšïk, led by Ólpësŋë, would start at Ïšš-Ënðó and continue east from there.

In 19 Ulta-Eimarae, the Battle of Raðvïš-Ïmrú occurred between the forces of Müžúökrš and Ðúrýlor. Here, Ðúrýlor had near double the amount of troops that Müžúökrš had, but to protect against multi-directional combat within the city (which was relatively unknown to them), they opted to stay just behind it, forming a long line to watch for any and all possible movements. Müžúökrš, seeing this, would concentrate all his men in a single horde and charge them at one end of the line. The path that they charged curved around the city bounds, using the city structures as camouflage. As such, the southern end of the thin line of Ðúrýlor was quickly punched through, and Ðúrýlor himself desperately reformed his lines in a west-east direction to stave off the charge.

Müžúökrš would line his army into a line roughly parallel to and south of the Ýbašïans. Crucially, this line was several hundred meters east of that of the Ýbašïans. In the resultant engagement, the eastern end curled around that of the Ýbašïans, acting to block any escape routes eastwards and southwards. The western end, however, saw the Këhóšians' line thin due to the extra ground they had to cover, and several hours of fighting from the Ýbašïans eventually overpowered this thinly-held line and began turning eastwards, rolling up the Këhóšian line as they did so. In response, Müžúökrš would quickly tighten the vice around the right end of the line, cutting off and enclosing around 750-850 Ýbašïans from the rest of the army. Of the roughly 2000 troops he had, 1500 were used to enclose and compress the Ýbašïan western line, while a mere 500 was devoted to halting the advance of the Ýbašïan eastern line. As such, the 500 defenders were subsequently slaughtered, as were the 750-850 Ýbašïans that were encircled by the remaining Këhóšians. A final charge by the Ýbašïans fimly beat back the Këhóšians, although they were able to escape before more casualties were suffered. By the end of the day, the Këhóšians had lost around 1,000-1,200 casualties, or approximately half of the total, while the Ýbašïans recorded numbers of 1,300-1,500. Nonetheless, it rendered the Ýbašïan army under Ðúrýlor tired and unhappy, and in the next day, the Këhóšians had stolen back into the now-deserted city of Raðvïš-Ïmrú to lick their wounds and recover. Ðúrýlor still kept his army in the distant outskirts of the city, as a means of preventing Müžúökrš from joining up with the other armies. He instead had faith that Kóvað and Sófëð would score a decisive victory at Vëlaš-Ïmrú, whereby the two warlords would then assist him in overrunning and wiping out Müžúökrš and his entire force.

First Battle of Vëlaš-Ïmrú

Subsequent to the Battle of Raðvïš-Ïmrú was the Battle of Vëlaš-Ïmrú between Ólpësŋë, the Khlúðŋúmïr of the Vakýë-Ëŋšïk, and the combined forces of Kóvað and Sófëð at the city of Vëlaš-Ïmrú. This followed the initial takeover of Ïšš-Ënðó, with Vëlaš-Ïmrú being the city to the east of it. By continuing east, Ólpësŋë and Hrülïšakr aimed not only to continue their leapfrogging campaign, but also to sow a substantial amount of dissonance and infighting that the warlords would then turn on each other. The battle that hinged upon all if not a substantial part of this was that of Vëlaš-Ïmrú, as the two generals opposing the Këhóšians had both been defeated on separate occasions and thus desperately needed a victory to retain their legitimacy in the eyes of their army. These generals were also at an advantage, as their combined force of 4500 was more than double the 2000 that Ólpësŋë had.

In the early mornings of 19 Ulta-Eimarae, Ólpësŋë led his army out of Ïšš-Ënðó and near the outskirts of Vëlaš-Ïmrú. Learning from the aftermath of the Battle at Ïšš-Ëmrú, Kóvað would keep all elements tightly-held inside the city of Vëlaš-Ïmrú, and installed constant watches across the landscape. These watches were the first to perceive the presence of the Këhóšians, and tracked their every move. After conducting several feigning movements to the right and left of the city, forcing the paranoid Kóvað to spread his lines out, Ólpësŋë decided to conduct a full frontal assault into the city. Due to the structure of the city's ruins, this had the army funnel through the central east-west avenue of the city. Although it initially went well, as Kóvað delayed in moving his flanks (as he was still confident that attacks on the flanks were to come), the central part of his lines began to crumble and he reluctantly had the flank lines swing into the Këhóšians that were bursting through. Unable to use the strength of his army in the narrow avenue, Ólpësŋë had the waiting elements of his army (left sitting outside the city) enter to the left and right by climbing over the various ruined walls. With the dreaded flank now appearing, Kóvað readily had his army steadily retreat from the fight, exiting through the avenue to the east and leaving the Këhóšians in full control of Vëlaš-Ïmrú. Kóvað would reunite with Šófëð in the outskirts and the two would discuss their next moves.

Second Battle of Vëlaš-Ïmrú

The next days saw the large-scale clearing out of ruins within Vëlaš-Ïmrú, as Ólpësŋë planned his next moves. On the second day (21 Ulta-Eimarae), Šófëð and Kóvað, whose combined force now sat at 3600, launched a combined assault into the city at the places that were being broken down, catching Ólpësŋë unprepared. A select few of the army members were in the process of breaking down the ruins and were thus slaughtered. The rest of the army mounted hasty defenses in two crescent-shaped layers (outside and inside), both centered at the exact center of the city. The outside layer crumpled fell back within an hour, and heavy fighting occurred in the inner lines. During this fighting, the lines were defined by the placement of ruins, with three streets separating one force from the other. Any assaults were constrained by the narrow streets, making them easily predictable and leading to a disproportionate loss of life. As such, the two were essentially locked in a stalemate for a long duration.

During that long duration, Šófëð and Kóvað thus devised a plan; a small group of Ýbašïans were to exit to the east, travel the entire length around the city, and reenter the city from the west, thus catching the Këhóšians in a pincer movement. This small group of around 500 men thus set out around the middle of the day, but to conceal their movements against the Këhóšians, they took a wide arc that unknowingly made themselves visible to the Këhóšians in Raðvïš-Ïmrú led by Müžúökrš. Ðúrýlor, also seeing them, recognized them as fellow Ýbašïans and took it as a sure sign that his southern counterparts were still alive and well, but Müžúökrš, understanding the geography and the westerly direction in which they were headed, became worried. As such, mere minutes after the 500 men dipped out of eyesight, Ðúrýlor and his entire force mounted a rapid movement that shocked Ðúrýlor, who immediately gave chase. With several scouts moving ahead while the rest of the army went at a moderate pace (to avoid being seen by the 500), Müžúökrš would follow them to Vëlaš-Ïmrú. He would also send a few men westwards to alert the Ïšš-Ëŋšïk, who were still on standby alongside Hrülïšakr.

The 500 reached the western end of the city near the end of the day, and initially, the Ýbašïans' ambush worked. Kóvað and Šófëð led a massive attack of their lines, flooding through the many streets of the city, and simultaneously, the 500 from the west flooded the main avenue. This led to devastating casualties at the confluence of the avenue and the streets and split the Këhóšians in two. Ólpësŋë himself, centered right at the avenue when this attack occurred, was one of the first to die. The two halves of the scattered Këhóšians fled outwards through previously-enlarged holes in the collapsed walls, and were still struggling against the pursuing Ýbašïans when Müžúökrš's forces appeared upon the horizon. Understanding the dire situation, he led his troops in a gallant charge towards the majority of the Ýbašïans he could see (those just west of the Vëlaš-Ïmrú) before swinging back and emptying the bloodied city of stragglers. Of Ólpësŋë's original 2,000, only 650 remained able enough to see combat; consequently, the Vakýë-Ëŋšïk and Öšërk-Ëŋšïk were combined and given the new name Müžúökrš-Ëŋšïk after their commander.

Kóvað and Šófëð reconvened with their army to the east of the city; typical estimates indicate that between 900 and 1500 died throughout the Second Battle of Vëlaš-Ïmrú's many engagements, leaving a measly force in the low 2000s.

Third Battle of Vëlaš-Ïmrú (Battle of Ðúrýlor)

The Third Battle of Vëlaš-Ïmrú arose immediately after the Second Battle at the same location, when Ðúrýlor, the third Ýbašïan commander, arrived to the carnage of the site around 2 hours after Müžúökrš had arrived. He found the Këhóšians within the ruined city, picking apart the piles of corpses, Engaging them from all sides, Ðúrýlor's men surprised and pushed the weary Këhóšians eastwards, into the forces of Šófëð and Kóvað, with the potential to seal them in a lethal pincer movement. However, some part of Ðúrýlor's lines lagged behind, perhaps due to the unfamiliarity of the terrain or physical fatigue or flawed leadership, but this momentary escape hatch was exploited by the Këhóšians. Their concerted assault into that delayed group completely split open and routed Ðúrýlor's lines. In the resultant chaos, Ðúrýlor himself was killed, and further attempts to pursue the Këhóšians were met with the just-arrived and rejuvenated force of Ïšš-Ëŋšïk. Unable to muster up any considerable fight, Šófëð and Kóvað were once again forced to make a retreat back out of the city, this time continuing further back to their own Ýbašïan lands.

Müžúökrian Campaigns

The ensuing weeks, from 23 Ulta-Eimarae to 16 Suta-Eimarae, saw the gradual recapture of all the inland Këhóšian towns that had been extensively raided by Ýbašý-Ýïr. This was carried out by the dual forces of Müžúökrš and Hrülïšakr, who brought more than 15 towns back under Këhóšian control. Most of these were only lightly damaged, and so during these few weeks, the majority of the action was spent strengthening them against future attacks of all kinds. This was done most effectively through the construction of rudimentary paths and directional markers that linked all these towns into a giant network, ultimately connected to the coastal towns. Concurrent to the construction was the encouragement by coastal leaders to spread into these inland towns, where they could help contribute to the growing victories of the Këhóšians through establishing a series of transport systems that spread the harvested crops throughout these towns. Through the settlement of these small-scale towns, the populace would also be creating a detailed layer of defense by which the tribe could resist any future invasions. Many of these volunteers, which easily numbered into the 5,000, even joined up with the army and traveled amongside them as they ventured further and further eastwards. By 16 Suta-Eimarae, the Müžúökrš-Ëŋšïk would rise from a battle-worn 1900-2100 to a rejuvenated 3,000, which marched closer and closer to the border of the Ýbašïans.

Phase 2: The Entry of Ërëšð-Ýïr, Šïbha-Ýïr, and Rlúýš-Ýïr

The approaching armies of Këhóš-Ýïr would alert the populace of Ërëšð-Ýïr, whose territory lay to the south of Ýbašý-Ýïr and bordered the Këhóšians on the eastern front. This concern was amplified when the Këhóšian army, hampered by the large cliffs on top of which the Ýbašïans resided, attempted to find a means to scale the cliffs by heading eastwards, directly approaching the Ërëšð-Ýïr territory. In 20 Suta-Eimarae, the first military encounter between the two armies would occur at the outskirts of the border.

Meanwhile the Ýbašïans, regrouped under the concentrated leadership of Kóvað and Šófëð, monitored the actions of the Këhóšians from atop their cliffs, adopting a purely defensive stance while looking for any opportunity to catch them off-guard.

Battle of Heta-Nüvïrïŋ

Things to be Amended (Old Stuff D:)

Battle of Caurriss

Caurriss was a town just southeast of Imotes. Angered by the trespassing of the exploratory group on Ipiasian territory, the warlord Suvend marched with a 5000 strong army with the intent of fully invading and controlling Këhóš-Ýïr. His route was to go southward of the cliffs, through Iristyir, before swerving back up and hitting the coastal towns that way. The northern part of Iristyir they walked through was filled with heavy desert, and as such the Iristyir and the Këhóš-Ýïr were never informed of their arrival. Suvend's troops arrived at Caurriss in 12 Ulta-Eimarae, much to the surprise of its residents. Coincidentally, Rauhler and his army were staying just opposite Suvend's forces, north of Caurriss. Upon hearing the news, Temest and the allied forces went out to meet them, while Rauhler focused on evacuating the civilians from the conflict. However, Suvend saw this and ordered a charge through the middle of the allied line, flooding through the now-empty city. Temest ordered a hasty retreat, but around 32% of the army was killed by the now routing Ipiasians. Temest himself was killed in the commotion. Having lost only 108 men, Suvend continued onwards to Imotes, where the vast majority of Kheosians were located.

Battle of Imotes

In 15 Ulta-Eimarae, Belhubyr fell into chaos as a reaction to the death of Temest during the Battle of Caurriss. As per the Pact of Imotes, the troops of both Belhubyr and Iristyir were fully under Rauhler's protection and as such, Rauhler's absence at the front lines of Caurriss depicted him as a traitor. Temest's heir, Gintor, rallied the rest of the Belhubyrian army and went after Rauhler, crossing the border at 17 Ulta-Eimarae. At the same time, Suvend's army was approaching Imotes from the south. Rauhler and the rest of Këhóš-Ýïr were still in Imotes, and as a last resort he and the civilians of Imotes sailed into the ocean, drifting for around 5-6 days before landing at Iristyir. Meanwhile, Suvend's and Gintor's armies clashed at the now-deserted Imotes, and each side automatically assumed the other was Rauhler's forces. After some heavy fighting, Suvend was pushed back and forced to retreat. Suvend lost some 2,300 men while Gintor had 1200 casualties. Gintor and his army only realized the true nature of their enemy when they searched through the bodies afterwards.

Battle of Iristyir Desert

However, just as he was going back across the border to Iristyir, they were met with a large force of around 3200 men, commanded by Rauhler himself. After landing at Iristyir and meeting with officials, they figured out that Suvend had used the desert path and, because of Gintor's significantly large army, reasoned that he would be traveling back through the desert. On 24 Ulta-Eimarae the two sides clashed, and with their spirits weakened by the earlier Battle of Imotes, Suvend and his army were all killed.

Treaty of Kollor

The Treaty of Kollor was signed on 30 Ulta-Eimarae by Rauhler, representing both Këhóš-Ýïr and Iristyir, and by the warlord Turillor, representing Ýbašý-Ýïr. In this treaty the two sides agreed to cease fighting; Këhóš-Ýïr was greatly ravaged by the war and Ýbašý-Ýïr's warlords were busy fighting another conflict. The land borders were to be how they were at that time, with Ýbašý-Ýïr's territory extending all the way to the cliff edges. From then on, the Këhóš-Ýïr-Ýbašý-Ýïr war was primarily fought between the combined forces of Këhóš-Ýïr and Ýbašý-Ýïr and Belhubyr, who had taken over the Kheosian territory.

Kheosian Campaign

The Kheosian Campaign was a military campaign that sought to take back Këhóš-Ýïr from Belhubyr. Rauhler led a small army of volunteers numbering around 1,500 from the Kheosian refugees and, with an additional force of 2,500 lent from the Iristyir, marched into Belhubyrian territory on 2 Suta-Eimarae, setting up camp in Caurriss and sending scouts further north, revealing to them a small patrol of around 400 men in Sulorrod and Enturim, and a large patrol group of around 1500 men in Imotes. The Kheosians decided to send half of their forces, led by Rauhler's friend Inganer, back to Iristyir and along the cliff edge, briefly entering Ipiasian territory before stopping just southeast of the Belhubyrian border. There they dug into the cliff from the top, creating a rockslide and a path downwards. This, however, attracted the attention of a Belhubyrian patrol group in Enturim as well as a small army group in Ýbašý-Ýïr, and Inganer was forced to hide. When the Belhubyrians and Ipiasians left the scene and headed back, Inganer and his army then descended down upon the cliff face and, after nightfall, they snuck into position north of Sulorrod. The following morning, Rauhler led his army to Imotes and engaged in a battle with them. The patrol groups in Enturim and Sulorrod were sent to Imotes as backup. However, just as the Sulorrodian patrol group was leaving, Inganer's army sprung upon them, quickly killing them and then heading towards Enturim. Meanwhile, Rauhler engaged the Imotes army with half of his army, feigning a lack of numbers. When Inganer had finished killing off the Enturian patrol, he went south towards Imotes. Rauhler immediately sent his reserve half of his army into the western entrance of the city, and with their army pushing in from the north, west, and south, they cornered and slaughtered the Belhubyrians against the eastern cliff face. From there, they concentrated their forces at Sulorrod, anticipating an attack from Gintor. However, unbeknownst to them, Belhubyr was in another war with Ýbašý-Ýïr and as a result, nothing happened at the border. For the rest of the Khólteðian Wars, nothing more went on, and so this is generally referred to as the official end to the Këhóš-Ýïr-Ýbašý-Ýïr War. Këhóš-Ýïr and Iristyir split up formally in 3 Wota-Eimarae, and by that time, all of Këhóš-Ýïr's cities were rebuilt and the tribe was back to its former self, albeit without the land on the cliffs.

Comments