Slavery

“A man in chains is still a man, but the chain convinces everyone else he is not.”

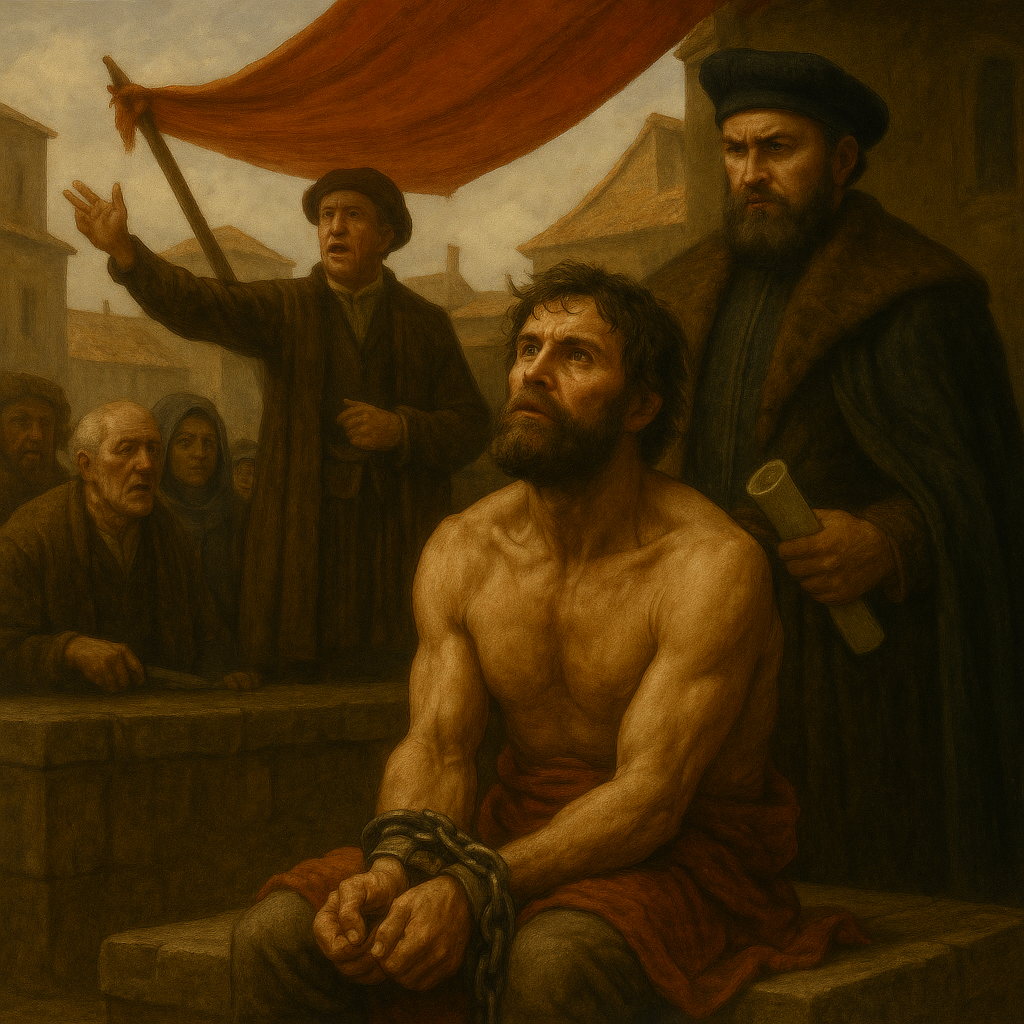

Slavery in Everwealth is no hidden shame but a matter of law and ledger, a system far, far older than The Great Schism but just as cruel. Where other realms disguise bondage behind euphemisms, here it is named plainly, a man in chains is property, and property is wealth. The Monarchy taxes it, the guilds broker it, and the markets thrive on it; more accurately thrive as-best-as this time of violence and scarcity allows. In theory, it is a regulated institution, licenses issued, tariffs collected, overseen by governors and their scribes. In practice, oversight is loose, and corruption bleeds through every rung of authority. Pirates put in at Wardsea or Gullsperch with holds full of stolen souls and, with the right satchel of gold passed to the harbor-master, their cargo becomes legitimate stock. Traffickers along our realm of The Folklands snatch the hungry, the debtor, the orphan, then forge papers after the fact. In these years of war, entire caravans of captives are sold without pretense, the paperwork written in blood and silence. The markets themselves are gaudy and grim, awnings stained with brine and dust, hawkers crying out prices as if bartering grain. Buyers paw at mouths and limbs, testing teeth, measuring scars, weighing whether the body before them will serve in a mine, a kitchen, or a brothel. The unskilled fetch little more than a sack of potatoes, but literate scribes, trained artisans, or those touched by magick are sold for fortunes. Bloodsports like fight pits or gladiatorial arenas are fed by this trade, slaves bought only to die in sand, their blood watering theatres in Opulence or rough rings and cold cages in Bordersword waiting to be bought and sold like produce. Some nights, the roar of a crowd for a shackled Orc torn apart by lions echoes louder than any sermon.

Brothels, too, are stocked by the trade, though spoken of more discreetly. Indentured courtesans, the ledgers call them, though the truth is plainer, smiles bought with chains, lives sold room by room. Such places are tolerated so long as they pay their dues, the priests and patrols often looking the other way for a cut of coin or flesh. Slavery is lucrative, too lucrative to vanish, too useful to reform. Nobles, governors, pirates, and guildmasters build fortunes on backs bent under the yoke. For every chain struck away, another is forged; for every outlawed pit, two more are dug in cellars and alleys. The wheel turns on coin and cruelty alike, justified by tradition, by necessity, by the lie of order. And yet not all bow to it. Tales persist of escaped slaves banding together in the highlands, raiding caravans, freeing others in turn. Some among widespread religious orders like The Knights of All-Faith thunder that bondage is a sin against the gods, though their voices are drowned in the market’s din. Songs sung low in taverns remind every free drinker that chains can change wrists in a heartbeat. Slavery, then, is Everwealth made manifest, regulated but corrupt, normalized yet despised, survival’s tool and despair’s engine. It keeps the mines dug, the fields ploughed, the arenas filled, the brothels open, and the coffers fat. And though The Monarchy insists it is managed, all know the truth. The kingdom’s wheel turns not because its spokes are strong, but because enough of them are bound in iron.

Origins and Regulation:

In recent decades, the burden of “oversight” has been stretched thin by corruption in Gullsperch and Merchant's Meet, where harbor-masters and scribes no longer even pretend to enforce law, but rather to auction it. Entire ledgers of slaves pass through the docks disguised as “dock apprentices” or “scribal assistants” under The Merchant's Consortium's seals, their bondage legalized with coin and convenience. The practice of enslavement began long before the chaos of the Schism, when famine, war, and the ruin of infrastructure forced desperate peoples to barter labor like coin, the first time, before rounding back around to it again thousands of years later. The first monarchs sanctioned the trade, binding it with tariffs and licensing, claiming it was better to regulate cruelty than let it run rampant. In truth, the crown needed the revenue, and the nobles needed hands. To this day, slavery remains “legal” under The Monarchy's law, subject to tariffs, documentation, and licenses overseen by governors and scribes. In practice, oversight is loose. Harbor-masters at Gullsperch and Wardsea will gladly stamp forged documents if the bribe is heavy enough. Merchants “lose” their ledgers when shipments of captives arrive in Bordersword. The Ironclad Republic of the dwarfs forbids slavery in name but turns blind eyes to slave caravans that bring metals, gems, and food. In many places, the official licenses to these captives is a carved inscription into the flesh of the slave with the name of their master. In others, the governor’s seal is pressed into wax mixed with ash from the burned homes of those enslaved. The crown calls it “administration.” The folk call it what it is, the law making sure the whip keeps cracking. The Scholar's Guild, though not openly implicated, is complicit by silence; their meticulous records and census ledgers are the very paperwork that keeps chains neat and deniable. Some whisper they even provide bell-ringers and “research aides” to the great observatories of Stargaze, where slavery has been sanctified under the guise of scholarship. Sources of Slaves:

Slaves come from many paths:

- War Captives: Prisoners taken in raids or full campaigns, particularly Elfese in the southeast and Orcs captured on the marches.

- Criminals: Convicts stripped of rights and sold to mines or military contractors. Thievery, banditry, or debt is often punished with chains rather than execution.

- Bandit Raids & Trafficking: Pirates and slavers seize travelers, orphans, and refugees. Such “cargo” is legitimized by bribes or retroactive paperwork.

- Indentured Servants: Those who bind themselves (or are bound by family) into labor contracts to pay debts. In theory temporary, in practice contracts are often extended until they are indistinguishable from lifelong bondage.

- Born into Bondage: The most insidious form. Entire generations of Minotaur, Giants, and Orcish are raised never knowing freedom, their value as laborers too profitable to release. To see a free Minotaur in Everwealth is rare; most are born into chains, branded and cataloged before their first breath.

Slavery in Everwealth is shaped by race as much as circumstance:

- Minotaur: Almost synonymous with slavery. Their immense strength makes them prized as haulers, quarrymen, and gladiators. Free Minotaur exist, but many bear scars of the yoke, or avoid Everwealth if at-all possible, their species subjugated to it practically their entire existence.

- Giants: Too valuable as living engines of labor. Used in construction, heavy transport, and war machines. Though sparingly as their ferocity and durability coupled with the prized strength their masters seek them out for can lead to devastating escapes or acts of revenge that cripples plantations; If not end it entirely as the ravenous scorned son of the northlands does not rip his chains in-two before doin the same to his subjugators and their little children in the dead of night.

- Orcs: Among the most traded peoples, captured in raids and sold by the hundred from Kathar for pit fighting or mercenary work. Their ferocity makes them favorites in arenas from Opulence to Twin-Peak.

- Elfese: Once masters of the land, some remain here humiliated as servants and field-hands, especially after their expulsion to the southeast. The irony is not lost, nor forgiven. Some wearing it as a branding of dishonor willingly, unable to defend their home from becoming Everwealth, they see no more-fitting punishment than to serve its new masters.

- Humans & Others: Debt-slavery and indenture are the typical nature of human slavery though many are still bound in chains, though often under a veneer of “service contracts.”

Though slave markets span the kingdom, three cities stand apart in notoriety: Gullsperch, where pirate cargo is washed clean into stock; Merchant’s Meet, where contracts cloak chains in daylight; and Stargaze, where military law all but ensures prisoners become commodities. The slave markets are both gaudy and grim. Sun-bleached awnings sag with dust and brine, hawkers shout prices as though selling grain, and buyers paw at teeth and limbs. Prices range from a sack of potatoes for an unskilled laborer to a chest of silver for literate scribes, artisans, or those touched by magick. Stalls in Bordersword are marked by blood on their wood, stains that no amount of rain can wash away. The smell of sweat, fear, and old piss lingers long after the crowds go home. In Kathar, slavers march in broad daylight with banners, as if daring the gods to object. Merchant’s Meet is the crown jewel of this economy, the “Market of Markets” where no stall is without its shadow, and no guildmaster too proud to count profit from chains. Slavery there is not hidden but performed with a brazenness that shames the crown itself, and yet no king dares close it for fear of breaking trade’s lifeblood. Key markets include:

- Opulence: Home to vast theatres and fight pits both state-funded or privately owned, where gladiators die nightly for the crowd’s amusement.

- Twinpeak: A mountain city infamous for slave-fighting rings, where captured Orcs and Minotauri are set against beasts.

- Bordersword & Catcher’s Rest: Frontier towns where traffickers sell “wild stock” straight off the road.

- Kathar: Ostensibly outlawed, but in practice rife with government-sanctioned slave gangs that function as mercantile cartels.

The “uses” of slaves in Everwealth are varied and brutal:

- Labor: Mines, fields, quarries, docks, and forges run on slave backs. Half-Giants haul timbers, Minotauri drag millstones, and Elfese labor in swamps where disease kills freemen too quickly. Accidents are frequent, and bodies are cheaper to replace than equipment, so corpses are often buried beneath the very stones they were forced to cut. The sound of chains in these places is said to echo louder than the picks and hammers themselves.

- Gladiators: Fighters purchased solely to die in sand. Amphitheatres in Opulence Crossing and rougher pits in Twinpeak thrive on their blood. The crowds cheer for spectacles of cruelty, demanding beasts, blades, and fire in equal measure, while the condemned are fed false hopes of freedom should they somehow survive. Few ever do, though their names live on as tavern curses and rallying cries whispered by other slaves.

- Military Auxiliaries: Some slaves are forced into warbands, outfitted with weapons and driven before armies. Shackled even in battle, they are sent ahead as fodder to blunt enemy charges, their deaths buying time for their masters’ troops. Those who dare turn their blades on their captains are hunted down by dogs and hung as examples, their bodies left to rot on pikes at the roadside.

- Sexual Exploitation: Brothels and “houses of service” often operate on slave labor, their ledgers calling them “indentured courtesans.” The truth is plainer: lives bought and sold room by room. Some slaves are traded so frequently between houses that they no longer remember their first owners, their names overwritten in ink with every transaction. Even whispers of escape are punished with mutilation, ensuring obedience through scars as much as threats.

- Domestic Service: Wealthy nobles and merchants keep slaves as house-servants, status symbols of ownership as much as labor. Gilded collars or branded livery distinguish them from freemen, transforming human lives into ornaments of prestige. Some are treated well enough to sing their masters’ praises, but most live in quiet fear, knowing that a misstep at the banquet table can see them sold into harsher fates by sunrise.

Slavery is one of the kingdom’s most profitable enterprises. It fills noble coffers, lines governor’s purses, and enriches pirates and guilds alike. Entire industries depend on it: mines, pits, brothels, docks, even religious institutions that tithe a portion of “indentured” labor. Every attempt at reform is swallowed by profit. For every chain struck, two more are forged. The Monarchy tracks slaves the way farmers track cattle. Their ledgers are inked in red, recording how much flesh was worth last season compared to this one. In famine years, the price of a starving man drops lower than a bushel of grain, and no one pretends to be shocked. Resistance and Rebellion:

Not all bow to the system. Escaped slaves band together in the highlands, raiding caravans and freeing others in turn. Rumors tell of whole camps of free Minotaur living in caves bamid The Battlement Cliffs. Much of The Knights of All-Faith thunder that slavery is sin, though their numbers are too few to challenge entrenched powers. And in taverns across Everwealth, low songs remind freefolk that chains can change wrists in a heartbeat. Religion and Morality:

Slavery is not merely tolerated but sanctified in some shrines, priests in Merchant’s Meet tithe on chains, while in Stargaze, slaves kneel in rags before the Wheel, their offerings taken by the same hands that struck them. The gods themselves are invoked to justify the practice. Some priests claim chains are divine punishment, others insist servitude purifies the soul. Yet dissent exists: rival cults whisper that bondage is the truest heresy, a violation of the Wheel of Elements and of mortal dignity alike. Whatever the dogma, in practice most temples accept the coin of slavers, their sermons conveniently silent. The songs of the freed are dangerous, outlawed in many markets. Some villages swear their protection to escaped bands, even knowing the gallows waits if they are caught. To harbor the chained is treason, but to refuse them is to sleep uneasily, knowing vengeance might come with fire in the night. In some shrines, slaves are made to tithe for their masters, kneeling in rags before altars while their captors drink the wine of offering. When the priests preach freedom of spirit, the slaves are told their chains are merely of the flesh. Such sermons often end with laughter, in the pews, not the pulpits. Only The Knights of All-Faith dissent with any volume. Their scattered sermons denounce bondage as heresy, insisting that no god of the pantheon sanctions such cruelty. Yet their voices are drowned beneath the roar of pits in Bordersword and the clink of coin in Gullsperch. Even their own chapels are divided, some hosting freedmen in secret, others too cowed by Consortium contracts to speak aloud. Everwealth in Chains:

Every attempt at reform collapses not in parliament, but in the markets themselves. The Merchant’s Consortium in Gullsperch, the Merchant’s Assembly in Merchant’s Meet, and the Syndicates in Bordersword all compete to keep prices low and profits high, their influence woven so tightly into Everwealth’s economy that to uproot slavery would be to unmake trade itself. Slavery in Everwealth is not a shadow institution but a mirror of the kingdom itself: regulated yet corrupt, normalized yet despised, a tool of survival and an engine of despair. It keeps the mines dug, the fields ploughed, the arenas filled, the brothels open, and the coffers fat. And though the Monarchy insists it is managed, all know the truth. The wheel of Everwealth does not turn because its spokes are strong, but because enough of them are bound in iron. Ask a free man in Everwealth if he feels safe, and he will not mention monsters or famine. He will look at his children and say “One bad winter, and they’ll be sold with the potatoes.” In famine years, Merchant’s Meet sets the prices for flesh as surely as Opulence sets them for grain. Ledgers circulate through Stargaze where captives are valued beside siege engines, their lives tallied not in seasons but in battles. Ask a gull in Gullsperch, a stargazer in Stargaze, or a merchant in the Meet where the kingdom’s spine bends, and each will answer the same, coin is heavier than iron, and starving pains the heaviest weight of allv. The wheel of Everwealth turns on chains not because the crown decrees it, but because no city dares imagine its markets without them.

Comments