Esimtugism

The One Faith, Reborn and Sanctified

'Đorʻiz ja đop đinuz uʻiwi nol jug xe nol titr̂o, xe pe gaha đop şai iwoz đaki xe iwoz zaxi, al hag zim gaiwip đu şegniz đop nuş opjar̂wip hith nuş đoşip ihji pe şat ihjişompou. Şegniz pul ripmum po er̂op uʻiwi pumma geʻgalhi şegniđeg no'poz. Ia ja đop xono is nol ik go noʻpoz zot đop jiʻni: "Ja nol ehu po uz şa rol uđI po ziz şa ziđI Judh şa puz joudh." Ia ja đop numu ru ja đop ginla ojildha it po gozip na ja đop numu po ezşa po Judh ukwawiwpitu.' 'Then I saw the seas split and quake, and from them appeared the black lightning and the black thunder. Yet within the centre of its blackness a fire burned brighter than the hottest steel from the greatest steel plant. The fire, which even the furious seas would not quell, blazed forth before me. When I asked who was presenting thyself before me, He answered: "I am the father of all fathers, the king of kings, grandfather of thy seed." When I heard it, I fell facedown, as I heard the voice of Judh speaking.'Excerpt from the Abarazian Letters, Abaraz 21.13-18 .

Practice

Prayer

Prayer, or nuhwu, is a fundamental aspect of Holy Rradzipaxy. It serves as a means for followers to communicate with Holy Judh and to honor the exemplary lives of the prophets, martyrs, and saints. The Rradzipaxian faith avoids both direct idolatry of saints and the exclusive worship of Judh. Instead, it positions saints and martyrs as spiritual guides who help elevate the prayers of the faithful.The Role of Saints and Martyrs

Eşimtugi believe that the souls (talluʻ) of righteous individuals who have achieved Theosis can act as intermediaries. These individuals, whom you can refer to as Tithuʻip ("final souls"), are not worshipped as gods but are highly revered. They are seen as having a closer connection to Holy Judh due to their spiritual journey and the self-annihilation of their ego (miʻek). The Tithuʻip are believed to have a unique ability to understand the spiritual struggles of the living, having experienced similar challenges themselves. This makes them ideal patrons for specific intentions.Saints and their Patronage

A person might pray to Şat Ujlao, a martyr-saint who endured great persecution, for strength in times of hardship. A family might seek the aid of Joz Jahto, the founder of the faith, for wisdom and clarity in a difficult situation. Instead of asking the saint to grant a wish, the prayer asks the saint to accompany the worshipper in their appeal to Judh, acting as a spiritual guide.This method of prayer is formalized as Nuhwu xipmum (stalking prayer), where the worshipper's devotion "follows" the spiritual path of a saint to connect with Holy Judh. This reflects the belief that one must "walk the path" of the righteous to attain spiritual closeness to the divine.

General Prayer, Rituals and Practice

Prayer is often a private matter, performed in a sacred place (miw) like a home altar (jiwhuz), a chapel (mathuz) or a temple (zadhu). However, communal prayers are also important, particularly during feasts (mehjo) or ceremonies (thow).The "Weaving" of Prayers

The act of prayer is often described as "weaving" (jaj) a spiritual fabric. The Rradzipaxian believer weaves their personal plea with threads of praise for Judh and reverence for the Tithuʻip. The goal is to create a beautiful and complex spiritual offering. This can be done through a repeated series of chants (mehtit) and physical actions like bowing (tarum).Recital of Scripture

Reciting passages would be a common form of prayer, helping the faithful connect with the prophet's original revelation. This is if possible always done in chant (mehtit), but can be done in whisper (zalho) if curcumstances don't permit for singing. The phrase "I am the father of all fathers, the king of all kings, grandfather of thy seed" is a commonly used mantra recited to focus on Judh's supreme authority and his personal connection to humanity.Sermons

Sermons, or tothlat (exhibit), in Holy Rradzipaxy are given by the Anchorites and are distinct from the main liturgical rite. They are seen as a "presentation" of the faith, serving to educate and inspire the congregation. Unlike the structured "Burning of Thunder" ritual (described further below), which is likely a fixed liturgical ceremony, the sermon format is more adaptable. They are usually given on different days from the main rite to allow for a dedicated focus on theological instruction.Time and Place

Sermons are given by Anchorites, who are also tasked with leading the Holy Rite of Zax-Nuşeg, but they are often scheduled at different times to prevent the sermon from overshadowing the liturgical rite itself. For example, the Holy Rite might be on the third day of the week, while a separate sermon may be on the fifth day of the week. This separation allows both the liturgical worship and the theological instruction to have their own dedicated space, preventing the two from being conflated. The setting for a sermon is usually a chapel (mathuz) or temple (zadhu), but it could also take place in a more informal setting like a parlor or salon (both called xixteʻ) for smaller, more intimate discussions.Rituals

The Holy Rite of Zax-Nuşeg

The central ritual of the faith, the Holy Rite of Zax-Nuşeg (Burning of Thunder), was a synthesis of a musical performance and a spiritual communion, serving a Sacramental purpose. It would be a journey of spiritual R̂aşumʻeg (self-annihilation), culminating in a symbolic union with Judh. The RitualThe Setting and Participants

The rite would be held in a temple, or Zadhu (Place of Zadhteg, or "prayer/worship"). The ceremony is led by an Anchorite or sanctified person (Eʻartar), accompanied by the temple's designated Ezaxu (player of the zaxu). The participators, known as the Eşine (voyagers), would gather in a circle, symbolizing the unified cosmos, but additionally also the maelstrom from which Holy Judh revealed itself to Admiral R̂ađip.The Ritual Stages

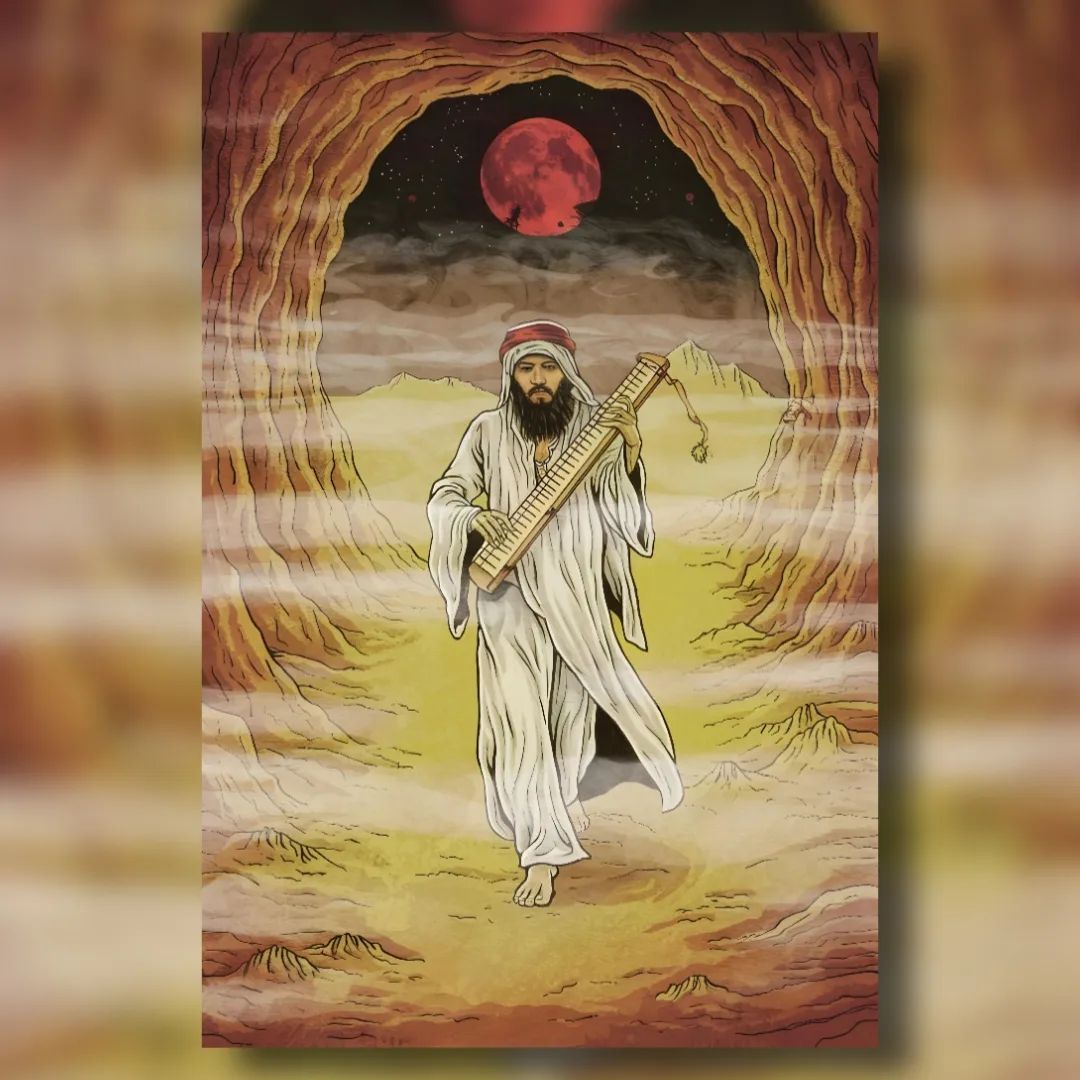

- Preparation and Invocation: The ritual begins with the Anchorite reciting a reflection on the journey to come, accompanied by a prayer. The Ezaxu begins to play a low, rhythmic drone on the zaxu, a sound called zaxiz ("the thunderous prelude"). This sound is meant to prepare the participants for the journey, reminding them of the initial divine act of creation. The priest present will then start singing from the Abarazian Letters, annals of the saints or one of the many sanctified poems of the saints. Elder members of the laity, designated as Đop Ga'ath (transl. They who have seen before) take over counter-clockwise from the Anchorite, chanting a full paragraph each.

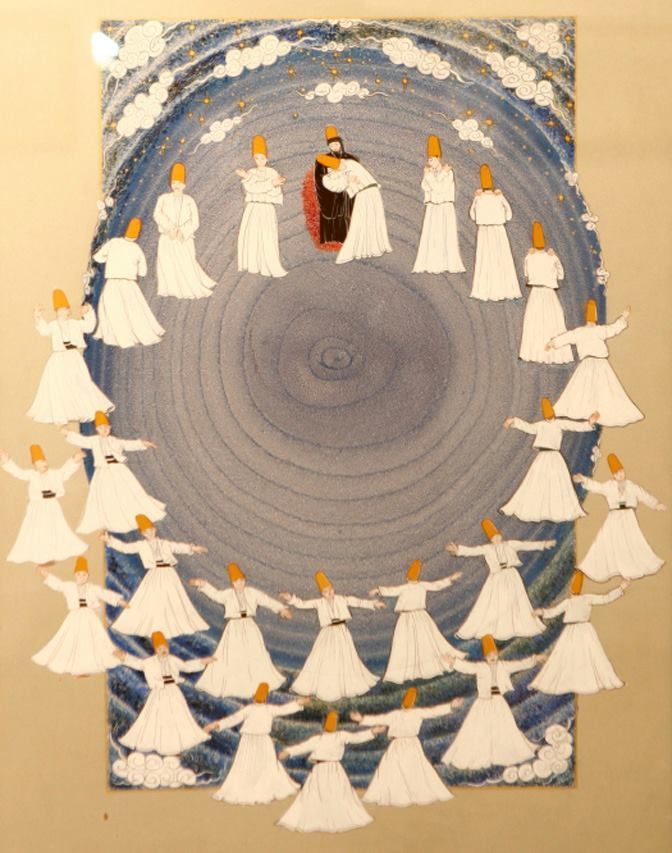

- The Journey (Po Ror): The music gradually becomes more complex and melodic. The Ezaxu plays a Ga'ath-Şu (Seeing-Song), a piece that is both rhythmic and tonally modular, designed to induce a trance-like state. Those among the Eşimtugi fit enough to do so would join in with a swaying, circular dance or movement, done counter-clockwise. This stage represents the "sailing" (şişompegoz, "the act of sailing") across the cosmic sea of existence. The goal is to shed one's worldly self and ego, or R̂aşumʻeg, in preparation for communion.

- The Annihilation (Po Nuşeg): At the peak of the trance, the music of the zaxu reaches a crescendo. The Anchorite presents a symbol of Judh's divine fire, which comes in many forms, but usually contains actual fire, such as a lantern, torch or a more ornate artefact. The Ezaxu plays a single, resonant note that hangs in the air, a moment of profound silence and focus. This is the Nuşeg, or "burning," where each participant's individual ego is spiritually consumed by the divine fire.

- Communion and Ukwaʻartareg: Following the trance, the Anchorite walks around and pours a small flask called a Ninhe'ekeg, filled with water from a holy well over the heads of each of the participants. This is the act of Ukwaʻartareg (having learned/achieved the Source's act). The water is usually quite cold, kept in ice before service, which thus also provides a certain degree of physical comfort after sweating heavily during the ritual. This is a representation of Judh's benevolent presence and the perfection that the Eşine strive to achieve. It is a moment of shared community and physical and spiritual restoration, seeing how the entire ritual often could take over an hour, where the individual, having symbolically annihilated their ego, is now one with the community and spiritually aligned with Judh.

Hierarchical Orginisation

The Holy Octrons

The Holy Octrons (Egudşimtugoz Xisoz) serve as the supreme collective leadership. The name itself, literally meaning the "Eight of the Admiral", refers to their function as collective heirs to R̂ađip. Their function in a federated manner, with each Octron elected by a different, geographically or culturally distinct region, ruling together as an ecclesiastical council. Regional Representation: The eight Holy Octrons would be elected from four major regions. This structure ensures that no single region dominates the church. Each region, therefore, would be represented by two Octrons, a representative of the Rikip and Eişip rites, reinforcing the theological diversity within the leadership. Theocratic Council: The Octrons would convene as a council, making decisions on doctrine, law, and church policy. This body would issue encyclicals and decrees, but their authority would be decentralized. They would be seen as the "collective face of Judh", embodying the concept of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts.The Arch-Anchorites

The Arch-Anchorites (Uxol-ʻđodhegrip) are the regional leaders. They function as bishops, overseeing multiple temples within their designated territory. The term đodhegri (anchor) refers to not only their spiritual positions as anchors of faith, but also as the vehicle by which R̂ađip was dragged to the deep, symbolising that through keeping his memory alive, his perpetual suffering drives humanity's purpose. The prefix uxol from xol (big) reinforces their status as "greater anchors." Arch-Anchorites would be responsible for ordaining Anchorites, resolving local theological disputes, and ensuring their dioceses adhere to the central tenets of the faith as decreed by the Holy Octrons. They would also be the primary link between the centralized leadership and the individual temples.The Anchorites

The Anchorites (Đodhegrip) are the parish priests. They are the frontline spiritual guides for the community, ministering to the faithful and leading worship services. An Anchorite's primary role is to lead the community in rituals, offer spiritual counsel, and teach the Razoz Withliti (Holy Traditions). They would be responsible for the day-to-day operations of their temple.The Elect

The Elect (Ukwaşugmu-eg) are lay people who have chosen to volunteer for service within the faith. Their exact roles differ depending on the rite. In the Rikip rite, they swear vows similar to the ones that the priests swear, albeit quite a bit lighter so that temple services can be combined with civil life. They are bound to fast, pray, always be present for services and do penance. In the Eişip rite, the Elect are volunteers that are rechosen each year. Although there is a ceremony attached to becoming one, unlike in the Rikip rite they do not ask to take a vow.The Hearers

The Hearers (Eşanumugiz) is the term for lay people who have made their vows yet don't directly aid in spiritual tasks. They are the vast majority of the believers, notably excluding any who have not come of age yet, since they could not have made their vows yet. Believers who have not made their vows yet, be it because of age or because they are in the process of conversion, are called Catechumens (Đikijle).Religious Cosmology

The Cosmic Sea and the Maelstrom

The foundational cosmological concept of Rradzipaxy is consistent on the devide between the Cosmic Sea (Hatiz Uʻiw) and Great Maelstrom (Jo'joki Thu'ihkoeg, literally "pulling from the great dephts"). This "Cosmic Sea" not a literal body of water but the totality of all existence—the ever-shifting, unpredictable, and boundless expanse of space and being. Just as the prophet-admiral R̂ađip was revealed to Judh from within a Maelstrom, humanity now exists within this vast and turbulent Cosmic Sea. The act of "sailing" (şişompegoz) is a metaphor for navigating this existence, which is full of both purpose and peril. At the heart of the Cosmic Sea is the Great Maelstrom (Jo'joki Thuʻihkoeg). This is the literal and spiritual center of the universe, the void from which Judh first appeared to R̂ađip. The Great Maelstrom is not a place of destruction but one of ultimate creation and divine power. It represents the Great Absence (Jo Irnit), the unknowable, ineffable essence of Judh. It is both the beginning and the end of all things, the source of creation and the destination of all souls who achieve Theosis through R̂aşumʻeg.The Afterlife: A Journey, Not a Destination

Rradzipaxian eschatology views the afterlife as a continuation of the individual's spiritual journey, a process that determines their final union with Judh. It is a system of spiritual consequence rather than a more traditionally envisioned reward and punishment system.The Fate of the Righteous: Post-Mortem Theosis

For those who live a righteous life and gain favour in the eyes of Judh, the afterlife is a final voyage toward Theosis, as the shedding of mortail coil supposedly makes the path R̂aşumʻeg easier to tread. Still, this process is widely believed to be agonizingly painful, as it involves the purification by the fires of Judh in the depths of the Maelstrom of Death. Souls that by the end of this process have achieved Theosis become entwined with the greater being of Judh. The union with Judh is described as becoming a thread in the Divine Weave (Jaj Judh). Just as a worshipper "weaves" their prayers, a perfected soul becomes an integral part of Judh's eternal creation, contributing to the order and purpose of the cosmos.Saints & Martyrs

The exceptions to this are the Tithuʻip (saints) and the "Tithuʻip rek Gupikul" (martyrs, literally Saint through Suffering), which are those who reach Theosis during their lifetime and thus remain spiritually intact throughout the passage through the Maelstrom and Holy Fire, or in the martyr's case were spared the passage by Judh on the basis of them already having gone through purifying suffering in life.. These souls, in the process to become Tithuʻip retain their own consciousness connected yet independent from the Divine Weave, which allows them to guide the living.The Fate of the Unworthy: The Spiritual Wreck

For those who fail in their divine task or commit the Forbidden acts, the afterlife is a state of spiritual consequence in wihch the soul is afflicted with Spiritual Entropy (Mat Jezgurki, literally "cut off sickness"). This is a chronic metaphorical disease that prevents the soul from achieving union with Judh. The afflicted soul is a Spiritual Wreck (Hut'tallu), forever adrift in the Cosmic Sea. It is unable to find the Great Maelstrom and is perpetually separated from Judh. This is a state of eternal suffering, not because of any physical torture or punishment but because of the soul's inability to fulfill its true purpose. By the end of the day, the ultimate fear within Rradzipaxy is not divine wrath but spiritual uselessness. While there is no dogmatised stance on the potential capabilities of these Hut'tallu to directly negatively influence the living. Such belief in evil spirits is widespread and varied and are considered "Rurko-Xer", or a non-heretical personal interpretation.Soteriology

Rradzipaxian soteriology assumes that those take up the faith take up a piece of the burden of responsibilities of the cosmos. This is why one is only taken into the faith officially after they make their own willing choice to do so, which always occurs after they come of age. Participation in certain rituals, such as the Holy Rite of Zax-Nuşeg, are only permissible for full Hearers of the faith.The Mandated (Jew'otlui)

Beyond the core responsibilities, a follower of Rradzipaxy takes three solemn vows during their coming-of-age ritual (or upon conversion). These are not merely promises but fundamental commitments that structure a devout life.The Vow of Zithwuth (Fairness)

The Recommended (Wirmux'ered)

These practices are not required but are widely encouraged as a way to deepen one's connection to Judh and embody the virtues of Rradzipaxy.The Daily Tihwu (Staple)

The Discouraged (Tuk'xered)

These are actions that go against the spirit of Rradzipaxy. While they aren't grounds for excommunication or severe punishment, a follower is encouraged to avoid them to maintain a pure and successful spiritual path. They often represent a failure to live up to the high standards of a faithful life.Thethup Hoh (Greed)

The Forbidden (Mox'ered)

These are grave sins that defy the direct will of Judh as revealed in the Zithwuth Şelʻe. Committing these acts would bring severe spiritual consequences and potentially ostracization, or worse, from the community. They directly contradict humanity's mandate to govern and defend creation.Woz (Unpermissable Murder)

The Rurko-Xer Classification

In Rradzipaxy, these practices that are neither required nor forbidden, but are instead matters of personal or scholarly preference, could be classified as Rurko-Xer (from rurkormu, "knowledge," and xer, "suggest"). This term signifies a "Suggested Knowledge" or "Matter of Interpretation," something that falls into the realm of theological opinion rather than divine command. This, along with the fact that the definitions of the Rurko-Xer are in frequent flux, gives rise to a richly debated spectrum of theological contentions within Holy Rradzipaxy.- Theological Status: A practice deemed Rurko-Xer is recognized as a valid path to spiritual enlightenment, even if it differs from another, or any, rites approach. This allows an Eişip follower to understand that a R̂ikip's ascetic diet is a legitimate form of worship, not a rejection of the divine gift of food.

- Federated Rulings: This classification directly supports the federated nature of the Holy Octrons. Since the council is composed of members from both the R̂ikip and Eişip schools, they can issue rulings that acknowledge and protect the distinct practices of each. A decree might state, "The consumption of meat on certain holy days is a Rurko-Xer, and both abstention (R̂ikip practice) and consumption (Eişip practice) are acceptable in the eyes of Judh."

- Personal Application: For the average follower, this provides a framework for personal choice. A young follower raised in the Eişip school might choose to experiment with R̂ikip asceticism as a way to deepen their spiritual journey, without feeling like they are leaving the faith. It allows for a flexible, personal path within the larger structure of the religion.

Syncretic Mythology

As with any religion, Eşimtugism has it's fair share of mythological legends and other oral traditions. Due to the highly syncretic nature of the faith, it has since its inception strived to include many legends older than the faith, or even pagan in nature, sometimes with shockingly little changes to the actual contents, which partly is the reason for the easy transition from those pagan faiths to the Rradzipaxian Temple.Generally, we can categorise mythological tales into a few catagories:

- Hagiographies: Biographical tales about Eşimtugist saints and martyrs. Notably, a lot of these tales, especially in rural areas, describe so-called Be'ath Tithuʻip (unseen saints), locally recognized saints not recognized by the main church.

- Folklore: Local tales, often quite old in nature, tend to always be originally pre-prophet beliefs adapted to better fit Eşimtugist world view. Especially in rural areas, folklore traditions can even outweigh mainline Eşimtugist traditions.

- Old Prophecies: These are actual pre-prophet pagan religious texts. While a lot of them are considered heretical by the church, many have since been altered slightly or been put in a different perspective, such as by recontextualizing characters within a more Eşimtugist framework.

The Temple of the Fourty Thousand Martyrs in northern Weşan is the site of the oldest Rradzipaxian temple of worship. The original concrete structure collapsed in 149 SC and was replaced by the current stone and steel temple by 170 SC.

The Nature of Holy Judh

Razip Judh (Holy Grandfather), also known as Uzmipi (Father of the Gods), is the sole deity of the Rradzipaxian faith. Through the revelations of the prophet-admiral R̂ađip, he was revealed as the creator of the world and of the Jexoz Ilkiʻi, (the First Children), also known as the Eithiz Mipi (the Old Gods) that roamed Argo before their disappearance at the start of the calendar. Within Rradzipaxy, he is seen as outside of timeless, formless and spaceless, with the vast majority of his being inherently unknown to the temple, a gap in knowledge that itself is deemed holy, the so-called Razoz Riki (Holy Mysteries). To Holy Rradzipaxy, there is no telling what Judh is not, yet through the words of the prophets and through the Razoz Withliti (Holy Traditions) of the faith there is at least some telling on what he is and what his expectations are for mankind. Judh is not a singular, anthropomorphic deity but rather the ineffable source of all being. The phrase "the father of all fathers" from the Abarazian Letters is not a literal description but a metaphorical attempt to grasp Judh's supreme, foundational authority over the cosmos. The faith posits that Judh is not "a" being but "Being" itself, an eternal, timeless, formless, and spaceless entity. This concept, known as The Great Absence (Rikiz Rura), is a central tenet of Rradzipaxy. It suggests that Judh is both everywhere and nowhere, simultaneously the creator of all and the void from which creation sprang. The Holy Mysteries are not secrets to be revealed but aspects of this divine absence that are inherently unknowable to mortal minds. This understanding of Judh explains the faith's prohibition on idolatry. Creating an image of Judh is seen as a foolish and blasphemous act, as it attempts to contain an infinite, formless entity within a finite, physical form. The only appropriate worship is through a life of purpose and action, as revealed in the teachings of the prophet-admiral R̂ađip.Scriptures

The Just Manifestation

The Just Manifestation (Zithwuth Şelʻe) were a foundational text of the faith. They were said to be the words revealed by Judh to R̂ađip in the Maelstrom. They outline the vision of Judh for humanity and the vow that R̂ađip made on everyone's behalf.Core Themes of the Zithwuth Şelʻe

The text would be structured around three key theological themes: The Fall of the Old Gods (Rurz-Rupe): It would detail Judh's disappointment with the Old Gods, not because they were false, but because their failure to properly guide humanity led to chaos and corruption. This narrative would explain why they were arrested and destroyed. The Hand of Humanity (Zimip Şap): The scripture would emphasize that mankind is no longer a mere flock to be herded by divinities. Instead, they are now Şum ʻi (defenders) and Şoş (doers), directly responsible for Turing (exalted governing) the world as the Old Gods were before them. This section would outline the Razoz'tuş (divine task) of protecting and nurturing existence. The Mortal Covenant: (Đişkaketoz Eldhi) The core of the Zithwuth Şelʻe would be a series of Şen ʻi (tactics) and Şum ʻi (defenses) revealed by Judh. These would be a blend of pragmatic rules and spiritual guidance, including instructions on how to handle R̂um (conflict) , deal with Şitje (suffering), and cultivate Rurkormu (knowledge). The text would stress the important responsibility of each person to live with a driven purpose, ultimately finding an appropriate place within the new church.The Abarazian Letters

The Abarazian Letters (Şigmiwi Abarazu) were another foundational sacred yet human-authored, and therefore fallible, text of the faith, compiled by the founder Joz Jahto. They consisted of eight books that narrated the religion's origins, core beliefs, and early history. Together with the Zithwuth Şelʻe and the Annals of the Saints, they formed the religious scripture of the faith.Summary of the Abarazian Letters

The letters begin with the Book of Jexoz, which establishes the supremacy of Holy Judh by recounting the downfall of the Old Gods (Eithiz Mipi). It sets the stage for Judh's divine intervention. This leads into the Book of Nuşeg, detailing Admiral R̂ađip Ujlao's prophetic vision of Judh, a central moment of revelation for the faith. The Book of Jauşo then codifies the principles and traditions that guide the faithful on their spiritual journey. The middle of the collection focuses on the life and legacy of the prophet. The Book of Hakwezo recounts R̂ađip's martyrdom at sea, teaching that sacrifice is a path to Theosis and spiritual union with Judh. The Book of Jahto follows, chronicling the efforts of the compiler, Joz Jahto, to spread the religion across the world, emphasizing its universal appeal. The final three books detail the faith's miraculous expansion. The Book of Uko describes the first miracle, which converted a single town. The Book of Xonʻi teaches about the power of faith to unite disparate people, symbolized by a miraculous coil. The collection concludes with the Book of Zaz, which narrates a final miracle that brought peace to a war-torn continent, establishing Holy Rradzipaxy as a religion of peace and compassion.

Comments