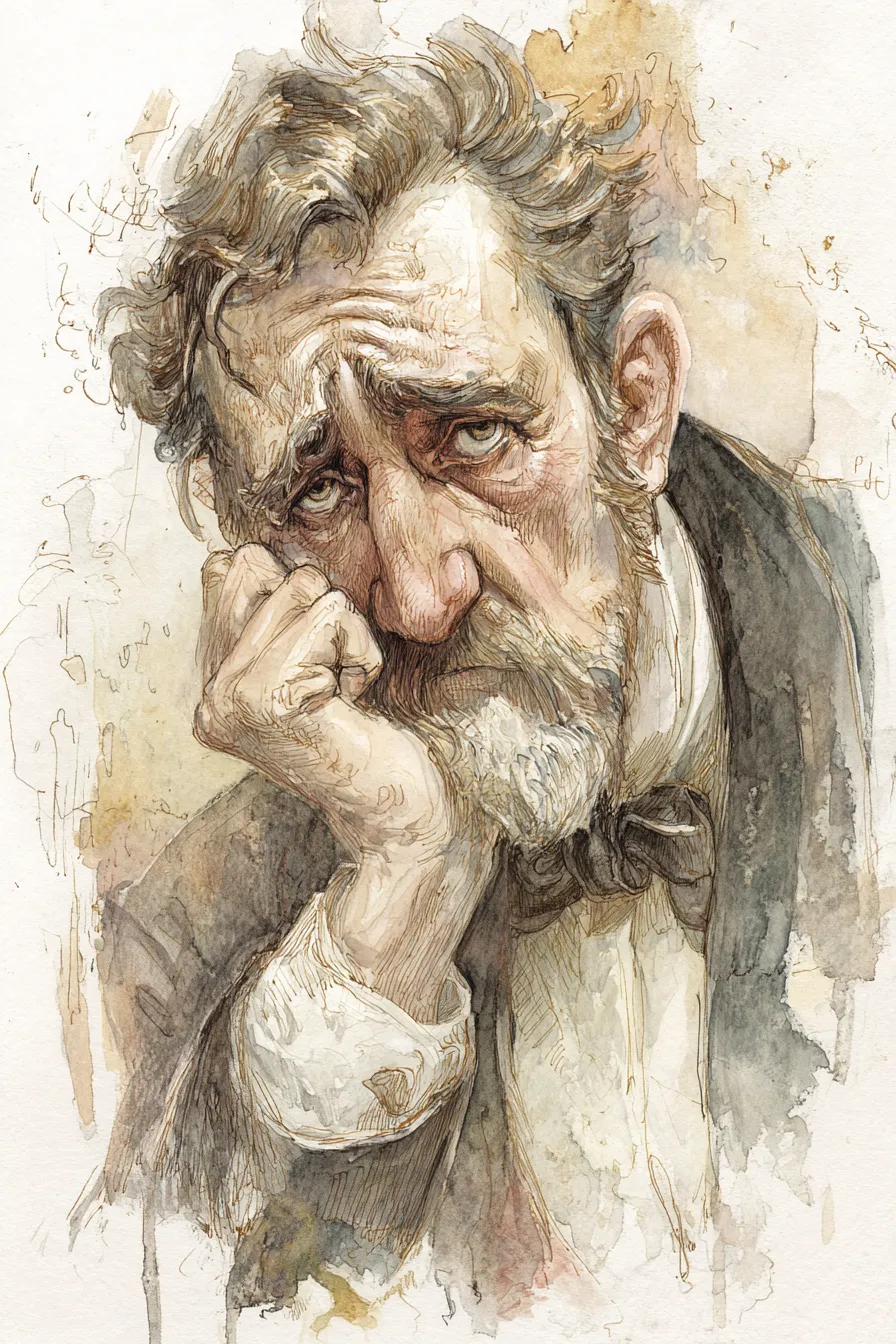

The Artigo and the Honourable Men

On alternate

Starsights, when the tide is obliging, Latchley can be found aboard the

Artigo, a ship turned auction hall moored in the harbour. The

Honourable Men - Bridgeport’s fraternity of discreet brokers - hold their sales there: ship’s chronometers, signal flags, half-legitimate curios, and the thing Latchley cannot resist - pipes. He keeps a cabinet of them in his office, each with a paper tag noting its provenance: a meerschaum carved into a hippocampus, allegedly smoked by an admiral who never lost a battle; a clay tavern pipe nicked along the stem, the very imperfection that saved it from being thrown out; a cherrywood churchwarden presented by a poet who paid his printing bill with verse and tobacco. He does not smoke them all - Matilda has views on the matter - but he dusts them, rearranges them, and tells their stories to any junior who lingers too long at the proofs.

"Honest bidder, soft heart, terrible poker face." -- Auctioneer aboard the Artigo

The slip, the pressure, the sale

For years the Beacon’s growth outpaced Latchley’s bookkeeping. Favourable rates promised to a charity were extended to tonic-sellers "just this once", invoices were paid twice under initials nobody challenged, and subscription monies went wandering under the gentlemanly title of "promotional allowances". It was not grand larceny so much as the soft creep of custom and hurry.

Lydia Quillston read the balances with a colder eye. She asked for a private meeting, brought no lawyer, and said very little. Latchley understood at once that he did not have an argument so much as an exposure waiting to happen.

"Mr Latchley’s heart is sound; his arithmetic needed sterner chaperonage." -- Lydia Quillston

A fortnight later Quill & Quire Limited - an entity he had never heard of - acquired sixty per cent of the paper. He kept forty, along with the title of Publisher and a smaller salary than pride would prefer. The staff were told the arrangement brought "stability" and "focus"; both words were true. Lydia sacked the lurid illustrator, retired three serials that sold smut as wit, and installed a decency code that made reporters reach for their better verbs. Latchley stayed on because he loves the pressroom and because the Beacon is as close as he has to a seventh child. He also stayed on because Matilda said, simply, that a man should tidy his own mess and feed his children.

The workday now

These days Latchley rises before the gulls and walks to the office while the streets still smell of tide and ash. He tastes the new ink with a sceptic’s frown - it is never as good as last year’s - and checks the formes for broken type. He writes a short "From the Publisher" on Thursdays, usually on matters safely civic: a bridge in need of repainting, a pensioner’s club threatened with closure, a plea for quieter fireworks. He convenes the morning conference, lets the editor and the city desk argue, and plays tie-breaker only when tempers fray. At noon he vanishes to the paper yard to talk delivery routes with Prudence and to slip Hugh a biscuit behind the

guillotine. In the late afternoon he walks the top floor and looks in on the composing room, where the younger hands still call him "Mr L." even when ink streaks his cuffs like a junior’s.

Lydia’s presence is felt rather than seen: a margin note in a proof, a red line through an immodest woodcut, a calm question about a source that was not as solid as claimed. Their weekly meetings are clipped and courteous. He resents her control in flashes and is quietly relieved by it the rest of the time. He is, after all, better at papers than paper-work.

Things he keeps and things he knows

Latchley’s office is a small museum of Bridgeport: ship-chandlers’ bills pinned to a corkboard, the first Beacon masthead in a cracked frame, the brass gavel the Honourable Men once let him hold when he outbid a naval captain for that ridiculous hippocampus pipe. He keeps a drawer of unsent letters to his children, begun and abandoned between proofs; another of apologies to advertisers he turned away after the decency code; and a third - locked - containing a ledger of favours owed on both sides of the water. He knows which councillor will trade a quote for a correction and which constable reads the Beacon aloud to his mother.

The marriage that steadies the ship

Matilda is no ornament. She spotted the first irregularity a month before Lydia did and told Percy, gently, that good men can still lose their way by inches. It was her insistence that made him stay on under the new order rather than sell out and sulk. She runs a small evening circle for the children of pressmen in their front parlour - reading, sums, the tidier arts of a good letter. When the house quiets, she hems, he proofreads, and between them there is enough peace to float a boat.

"Percy would rather miss a meal than a deadline." -- Matilda Latchley

What he wants now

He wants the Beacon to outlast him, ink steady, paper paid, apprentices turned into foremen with ten fingers between them and no fewer. He wants his children to choose their own trades without thinking they must shoulder his. He wants, one day, to write a piece of plain thanks to the city that let a handbill grow into a paper - and perhaps to the woman who kept it from going crooked. And on Starsights, if the tide runs kindly and the Artigo rings its bell, he wants nothing more exotic than the warm weight of a new pipe in his palm, a good story attached, and the knowledge that he has won it honestly.

Pocket Botany for Busy Citizens

Sea Thrift (Armeria maritima), or the Little Lighthouse in a Skirt

By "Hedera"

If you have ever walked the Duke's Downs and seen, at your boot-tip, a tiny globe of pink bobbing as if it had somewhere important to be, you have met Sea Thrift - also called Sea Pink, also called, in my house, "the polite pom-pom". It is a cushion-forming perennial that loves the things most plants disdain: wind, salt, and soil so poor you'd hesitate to bury a coin in it. Thrift thrives where grander flowers faint, which is one reason lighthouse cottages have long favoured it. Another is bees. A thrift patch is a bee's tea room; the hum comes free with the view.

Each plant makes a tidy tussock of needleish leaves, and then - most obligingly - hoists its flowers on slender stems to keep their skirts out of the mud. The heads last for weeks if you do not fuss. (People who fuss at thrift are the same people who stir jam before it sets. Resist.) Water sparingly, avoid fat composts, and give it a sunny spot that feels a little unfair. It will adore you for the neglect.

Bridgeport folklore recommends tucking a sprig of thrift into a coil of rope for safe return from a voyage. I do not pretend botany can out-argue a storm, but there is sense in the charm: thrift's scientific name comes from armarium, a chest or store; it stands for provision, for keeping one's courage - and one's pennies. Children like it because the flowers are perfectly child-sized; dock cats like it because it makes a springy green pillow; editors like it because it spells itself without quarrel.

A word on manners: do not strip it from the cliff paths. Thrift is happy from seed in a shallow pot, or divided, gently, from a friend's clump after flowering. Press a few heads in a heavy book and you will have, by autumn, the most amiable bookmarks in Bridgeport - little lighthouses on paper, guiding you back to your place. If the city must be busy (and it must), let your windowsill be calm. Plant thrift, and give your bees somewhere pleasant to read the headlines.

Sea Thrift by Tillerz using MJ

Brought to you by

Brought to you by

I bet he is proud that many of his children seem to be into the business. I think my favourite is Beatrice though.

Explore Etrea | WorldEmber 2025

:D Still need to think about some plot hooks, and some secrets.