Dragons

Sovereigns of a Forgotten Age

"From my earliest recollections, the dragons have stirred something trembling and incandescent within me. Titans of flesh and flame, equal parts wisdom and wrath, majesty and monstrous pride. Had I possessed even a scrap of daring, I might have sought one out! But no, cowardice has been my lifelong companion, and the mere scale of such a being would surely reduce me to quivering pulp. I struggle enough with conversations conducted at eye level. Yet I take comfort in the tale that dragons boast scholars too among their kind.

Perhaps, in some secluded den, a draconic Arvandus crouches over his own manuscripts, penning wild theories about the capricious habits of humankind, dreaming of meeting one face to face. The cosmos delights in its little jests; I choose to believe this is one of them.

While the most common phenotype is that of a massive reptilian creature with scales, leathery wings, a horned skull, and a sweeping tail, draconic morphology is actually staggeringly diverse. Countless species and subspecies have adapted to Netherdyn’s many biomes, from aquatic dragons to variants with more mammal-like traits.

The origin of dragons remains one of the most fiercely debated questions in both scholarly and religious circles. What is generally agreed upon is that during the Age of Paradise, dragons were venerated as demigods, entrusted by the Divine Parents with roles as protectors, messengers, and arbiters among the Firstborn Kin.

Yet despite this shared history, coexistence between dragons and other peoples has always been fraught. Their territories, instincts, and ambitions often place them in direct rivalry with the kin, leading both groups to evolve societies, languages, and traditions parallel to one another.

Biology of Dragons

Classifying traits shared by all dragons is challenging, given the extraordinary diversity of their biology. Depending on species, dragons may be carnivorous or herbivorous, ectothermal or endothermal, aquatic or terrestrial, and covered in scales, feathers, or even fur. Yet despite this diversity, several anatomical features are universal. Every dragon is quadrupedal for example, with wings, a tail, and horns as standard features. They also share a hybrid limb structure combining aspects of both paws and hands: the front limbs end in five clawed digits, including a fully opposable thumb, granting them remarkable dexterity. This specialized limb structure allows dragons to manipulate objects with precision and purpose. It is traditionally referred to as a dragon’s "talons". Calling them "hands" or "paws" is considered highly disrespectful and may provoke offense.

Dragons universally hatch from eggs, even in species exhibiting mammalian traits, such as Russetmane Dragons. Lifespans vary by species but generally range from 1,200 to 1,500 years, making dragons among the longest-living creatures of Netherdyn. Different terms categorized a dragon by age: hatchlings from birth to five years, dragonettes from five to fifteen, drakes from fifteen to around thirty, and fully adult dragons after thirty years. Elder dragons, those surviving a millennium or more, are revered as wyrms.

Dragon and Gender

Dragonkind exhibits a unique relationship with sex and gender, reflected in both physiology and culture. The draconic language recognizes four gender expressions: Rhaan, Kaanah, Dvarakor, and Kel’un. Hatchlings are born Kel’un, without biological sex. Only as they mature into the dragonette stage, typically between five and fifteen years, a young dragon’s body gradually develops into either Rhaan (male) or Kaanah (female). This process is largely subconscious. The dragon's physical form simply attunes itself to their innate identity, developing the corresponding reproductive organs of a Rhaan or Kaanah. As a result, a dragon’s gender generally aligns with its biological sex. This physiological adaptability does not fade with age. While most dragons will settle into a single sex for their entire lifespan, in rare instances, a dragon may undergo a second metamorphosis later in life, sometimes even after centuries. These events are often linked to significant life changes or deep-seated shifts in their identity.

The fourth gender, Dvarakor, represents dragons capable of consciously choosing to change gender as they desire. The physical process is a slow metamorphosis, referred to as Thur'Kaana (from Thur- "Shape," and Kaana- "of Life/Self"), lasting roughly six months for most reptilian dragons, and up to a year for more mammal-like variants. This period typically involves significant hormonal shifts and mood swings. Another uncommon variation is dragons that remain in the genderless Kel’un stage permanently, never developing into male or female.

This biological truth has profound implications for dragon culture. With gender being a fluid and personal state, societal roles are rarely, if ever, limited by it. A Rhaan is just as likely to lead a Qor-Kalon (a dragon roost) as a Kaanah. However, this egalitarianism does not diminish the deep veneration reserved for motherhood. Dragons are not as fertile as the shorter-lived kin, and the act of bearing and laying eggs is considered a sacred contribution to the future of their kind. The hatchery is often the most heavily fortified and revered location within a Qor-Kalon, and the laying of a new clutch is an event marked by solemn ceremony and celebration.

Draconic Instinct

Dragons possess a hereditary instinct, a kind of sixth sense, that has been extensively studied in the field of dracology, yet remains only partially understood. In the draconic tongue it is called the Ahrkess. It is best described as a deep, central "gut-feeling" that all dragons share, an undercurrent of awareness that governs their sense of territory, their survival responses, and much of their mating behaviour. There is growing evidence that the Ahrkess also plays a decisive role in the development of a dragon’s sex, and in the rare changes thereof later in life.

The most visible function of the Ahrkess is territory imprinting. When a dragon claims a lair or region, their Ahrkess "imprints" on that place. From that moment on they experience a heightened awareness of intrusion, theft, or disturbance within their domain. To the dragon, this manifests as a visceral unease, a tightening in the chest or a restless agitation that grows stronger the more serious the violation. Dragons are also significantly more resistant to enchantments and other subtle mental influences while within their imprinted territory, making them considerably more dangerous when confronted in their own dens. Dragons also can sense when a territory is already claimed by another dragon’s Ahrkess, perceiving it as a kind of subtle pressure or "scent" on the air. This allows them to navigate the world’s vastness with surprising certainty, avoiding rival domains or seeking out potential mates.

Although the Ahrkess most commonly binds to places, it has been observed to occasionally imprint on specific objects, other dragons, and even kin. A hoard-item may become so bound to a dragon’s Ahrkess that its theft causes genuine psychic distress. More rarely, a dragon will imprint on an individual — sometimes a mate, sometimes a clutch-mate, sometimes, inexplicably, a kin. In these cases, the imprinted individual may exhibit faint echoes of the Ahrkess themselves: fleeting sensations of danger to the dragon or their shared territory, or an unexplained certainty that they are being watched. How and why this bond forms is entirely unclear. Such cases are too rare, and controlled experimentation too fraught, for the phenomenon to have been properly studied.

In this frenzy, dragons are capable of startling feats. They can continue fighting through grievous wounds, ignore pain and exhaustion, and display erratic, unpredictable tactics that make them dangerous even to allies. Many draconic cultures view such frenzies with an uneasy mixture of awe and shame — understandable in defense of a clutch, but dishonourable if unleashed over mere insult or greed. In the most extreme cases, when a dragon pushed into frenzy appears to be killed, the dragon often collapses into a torpor rather than truly dying. To outside observers this pseudo-death is virtually indistinguishable from actual death. The dragon’s breath slows to near stillness, their body cools, and even magical examinations often fail to detect more than the faintest lingering spark of life. Yet in this torpor the Ahrkess fights on, forcing the body to repair itself just enough to sustain a return.

There are confirmed accounts of dragons awakening from such a state after weeks or months, even when their injuries had been deemed unquestionably fatal. Typically, they do not heal perfectly; scars, missing limbs, or damaged organs may remain. Nonetheless, this death-refusing aspect of the Ahrkess is one of the reasons why dragons are so notoriously difficult to truly slay. Many a would-be dragonslayer has learned too late that the "corpse" they plunder is only sleeping. Usually when it wakes up to seek revenge.

A Scholarly Classification

The Althorn Foundation also categorizes dragons by their unique biological traits into different clades. However, as new species of dragons are frequently discovered that fit none or even multiple of these definitions, the academic literature is occasionally updated and changed. Currently, the Foundation maintains a list of the following classifications:

- Archidraco Clade: Also known as "Imperial" or "Classic Dragons," this clade represents the archetypal draconic form against which all others are often measured. They are the most common and widespread type of dragon, inhabiting mountain peaks, volcanic calderas, and ancient ruins. Their bodies are typically covered in thick, reptilian scales, and their elemental affinities most commonly manifest as fire, though lineages that command lightning or frost are also well-documented.

- Avian Clade: Also known as "Feathered Dragons". While still quadrupedal, their morphology shows significant avian adaptation. Many are covered in a mix of scales and brightly colored feathers, with wings that are more bird-like in structure, granting them superior speed and agility in the air. To facilitate this, their bone structure is often lighter than that of other clades and they tend to be smaller in size. They make their lairs on inaccessible cliff faces or floating islands.

- Pelagic Clade: Also known as "Sea" or "Aquatic Dragons." These species live either on coastlines, islands, or even fully within the sea, and typically have gills and fins in addition to their lungs. Their bodies are often sleek and serpentine to better navigate the water. The existence of deep-sea dragons is also speculated, but not yet confirmed. These unverified reports describe immense, bioluminescent leviathans that dwell in the abyssal dark, reaching down into the Charybdis.

- Therian Clade: Also known as "Beast" or "Mammalian Dragons." These dragons commonly have fur, are endothermal, and the females have teats and produce milk to feed their young. Therian dragons also tend to have a stronger draconic instinct, a more potent Ahrkess, than most other dragon types, which makes them more territorial and easier to push into an aggressive frenzy state. This heightened instinct gives them a reputation for being fiercely protective and quicker to anger, a trait often mistaken for simple aggression by outsiders.

- Phytosian Clade: Also known as "Flora Dragons," and as the name suggests, they are part plant. This classification covers a wide spectrum, from dragons that can grow certain plants on their bodies to those that seem to be more plant than dragon. Their relationship with flora is deeply symbiotic; some are capable of photosynthesis to supplement their diet, while others are known to exhale clouds of soporific pollen or corrosive sap.

- Chthonian Clade: Also known as "Subterranean" or "Deep Dragons." These dragons can be found in the Swallowing Depths or, in rare cases, even in the Void Below. This category is the least explored, as only very few dragon species of this type have been studied. Fragmented evidence and harrowing reports hint at the existence of many more. Specimens recovered from the upper depths often show adaptations to total darkness, such as atrophied eyes and enhanced tremorsense. The idea of dragons native to the Void Below is a terrifying prospect, suggesting a form of life intertwined with Netherdyn's most alien and hostile realms.

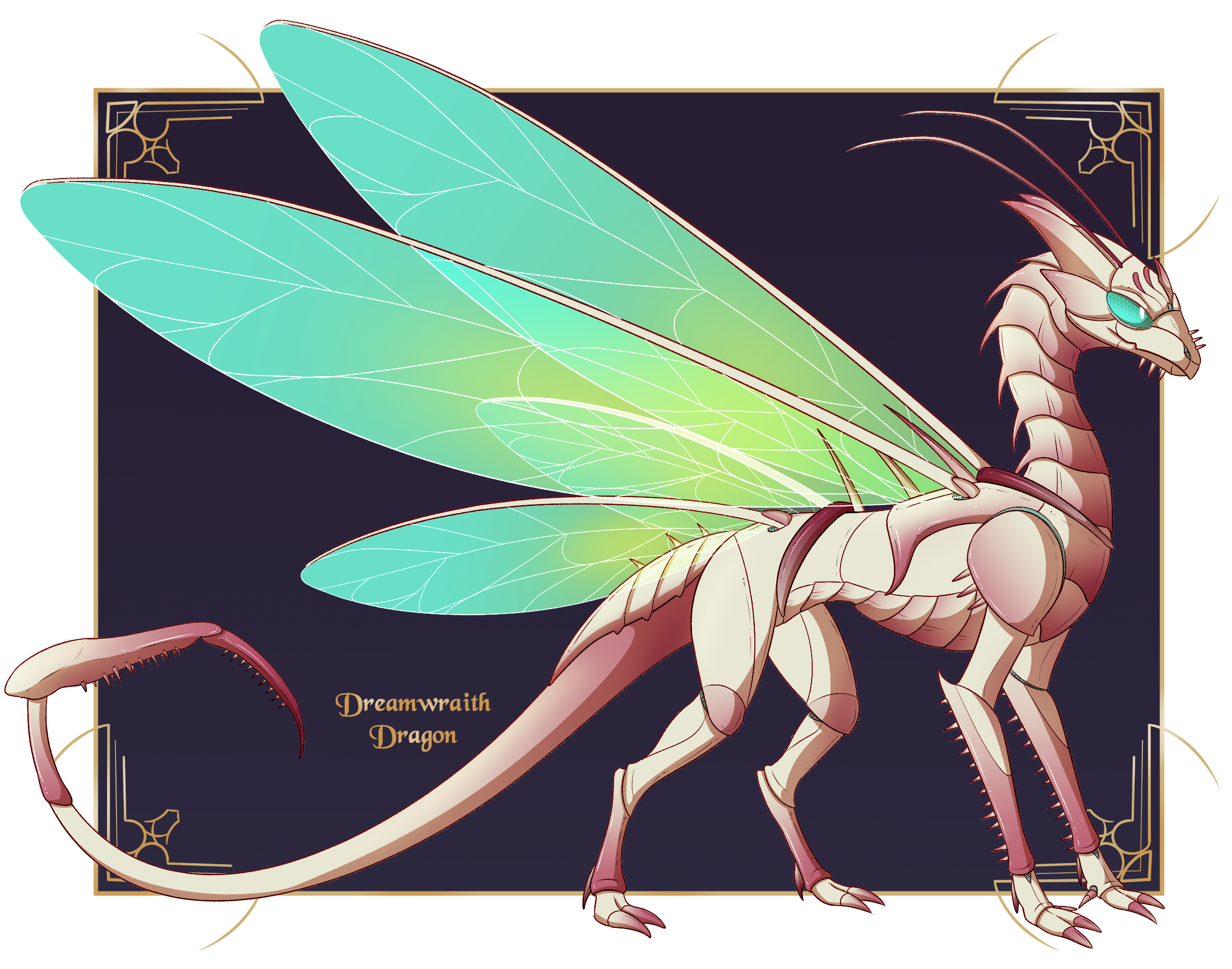

- Pseudodragons: This category describes all creatures that share draconic traits but not their history or fundamental nature. Crucially, this is a classification of origin, not merely size. Pseudodragons are not native to the draconic lineage of Netherdyn. They are dragon-like beings from the Otherworlds, such as the insectoid Fae Dragons, or Mirror Dragons of Kaleidalis. While they possess a similar body plan (quadrupedal, winged, tailed), their biology and social structures can be fundamentally different. True dragons often view them with contempt, seeing them as mockeries or flawed echoes of their own kind.

Culture and Society

Contrary to common kin assumptions, a dragon's species has little bearing on its social inclinations; examples of both solitary and communal life can be found across all clades. The draconic language itself has developed specific terms for these arrangements, which dracologists use to classify them.

G'Dar

The most fundamental state is that of the G'Dar (literally "Lone King" or "King of Self"). This term refers to the popular solitary lifestyle in which a dragon remains self-sufficient and isolated.Within draconic society, this is sometimes viewed as a juvenile phase, as young dragons often spend a period of their lives alone after breaking away from their birth-clutch. However, many dragons find this independence so suitable that they maintain it for the entirety of their long lives.

Ryn-Kalon

A more ambitious variant of solitary rule is the Ryn-Kalon (from Ryn, "ruled," and Kalon, "roost/home," often translated simply as "kingdom"). In a Ryn-Kalon, a dragon or a small group of dragons claims dominion not just over a territory, but over all peoples within it.The nature of this rule can vary wildly, from a symbiotic guardianship to outright tyranny. The most common examples are dragons who rule over tribes of kobolds, who often worship them as gods. But it is not unheard of for a powerful Therian dragon to claim an entire forest, making any dryads or faunlings within its borders their personal subjects.

Qor-Kalon

Finally, the Qor-Kalon (from Qor, "collective," and Kalon, "roost/home") describes a true community of dragons and is by far the most complex social structure they build.A Qor-Kalon typically consists of a single species claiming an entire region, such as a mountain range or a stretch of coastline. However, multi-species collectives are known to form, often out of necessity when two clans merge for mutual protection or after one has conquered the other.

Historic records indicate that Qor-Kalons were a rarity in ancient times, but as the realms of kin expanded and more dragons were displaced from their ancestral homes, these collectives became more common, a means to defend their territory and drive away would-be intruders.

With such a density of draconic life comes the necessity of a clear hierarchy. At its apex stands the G'Veyrn, the "First Dragon," who holds ultimate authority. Responsible for the defense of the territory are the Kress, or "Talons," a warrior caste led by the G'Kress ("First Talon"), who typically serves as the G'Veyrn's military right-hand. As a Qor-Kalon grows in complexity, it may appoint other specialists, such as a Zulmah (from Zul, "Truth/Law", and Mah "Tongue/Speaker"), an arbiter tasked with resolving internal conflicts; the Jor-Vals (from Jor, "Distant/Sky", and Mah "Eye/Voice"), who act as scouts and spies; and the revered Ovah-Sahl (from Ovah, "Egg", and Sahl "Tender/Carer"), a "Nest-Tender" responsible for the well-being of the hatchery, among numerous other roles that ensure the community’s stability and prosperity.

The Living and Dead Language of Dragons

Most dragons can learn to understand kin languages, but speaking them is a considerable challenge. Their vocal anatomy, like throats, larynxes, and palatal structures, are built for power and resonance across vast distances, and struggle with the fine consonants and fronted vowels common to most kin tongues. As a result, their attempts at such speech often sound awkward, harsh, and strained. Conversely, most kin find speaking draconic physically taxing, as it forces them to strain their vocal cords to produce the necessary deep, chest-driven growls and guttural sounds.

Draconic is not a single tongue but a vast and ancient language family, considered one of the most complex linguistic systems in Netherdyn. At its root is the original Ur-Draconic, a language so ancient and abstruse that only fragments can be translated; no living being is capable of fully understanding or speaking it. Its alphabet is believed to have contained over 300 distinct characters, though only 74 remain in common use. The meanings of the others have been lost to time. Consequently, even modern dragons speak what is essentially a simplified version of their ancestral tongue.

The most common modern variant is referred to as High Draconic, Veyrn-Kor'a. Its speech is deep and resonant, filled with hard, grinding consonants that evoke the sound of shifting stone. While most dragons first learn a regional dialect, any with a modicum of education or ambition eventually learns Veyrn-Kor'a, establishing it as the lingua franca of their kind. It is also the form most often learned by dedicated kin scholars and mages.

Beyond this standard, numerous dialects have evolved. Among aquatic dragons for example, Syn-Kor'a ("Deep Tongue") is a highly tonal and melodic variant adapted for communication across vast, water-filled distances. Using long, resonant notes reminiscent of whale song, it loses the harshness of its terrestrial cousins in favor of strangely musical, flowing sounds. In stark contrast is Nid-Kor'a ("Small Tongue"), colloquially and often derisively known as "Yip-Yip." This primitive, simplified version spoken by most kobolds drops the complex grammar of High Draconic for a direct subject-verb-object structure, its sound being faster, higher-pitched, and incorporating more hisses and clicks.

Two other variants are notable not as conversational dialects, but as highly specialized, functional languages. Poetic Draconic, or Bahl-Kor'a ("Beautiful Tongue"), is an intricate, artistic form used by Tale-Singers for epic poems and songs. It is believed to incorporate grammatical rules and even characters from the long-lost Ur-Draconic, making it almost incomprehensible to the uninitiated. Finally, there is Vael-Kor'a ("Binding Tongue"), known to kin spellcasters as Arcane Draconic. It is not a language for communication but a tool for Applied Spell Theory, reduced to a ruthless, practical minimum of phonetic and resonant elements proven to produce direct effects in incantations. To a native speaker, its phrases are often nonsensical, yet its efficacy is so well-documented that it is used by both dragons and kin alike.

The Legend of Draktharach

The shared mythology of all dragonkind revolves around the concept of Draktharach, a mystical realm where dragons rule supreme, a paradise undisturbed by the Age of Silence and modern strife. According to the most common draconic tales, dragons were either the first creations of the Divine Parents during the First Shaping or were their companions who arrived in Netherdyn alongside them from beyond the Sea of Night. Ancient depictions show dragons as guardians of the Firstborn Kin — wise arbiters, teachers, and friends who served as the direct link between mortals and the gods. However, when the Firstborn Kin invited demons into the realm, the Divine Parents abandoned their creation in disgust, leaving them to their fate. Though blameless, dragonkind was also left behind. Despite this, dragons held true to their divine purpose, guarding the Firstborn from the encroaching forces of the Netherhells. Ancient texts speak of a great bastion they created, a sanctum where they took their charge to watch over them in safety. This realm was known as Draktharach.

The exact nature and whereabouts of Draktharach, however, remain a mystery. Though multiple ancient texts corroborate the existence of such a domain, no empirical evidence of the fabled location has ever been found. This has led to various interpretations from both kin scholars and dragons themselves.

Interpretations of the Myth

One school of thought posits that Draktharach did indeed exist as a physical place, but it either fell to the overwhelming attacks of the Netherhells or simply evolved into existing lands, its original name forgotten by time. While plausible, no theory has ever conclusively identified which region was once the fabled land, nor how or when it ceased to be ruled by dragons. Hundreds of books proposing various timelines have been written, but none have withstood scholarly scrutiny.

A second, more introspective theory, quite popular among dragons, views Draktharach not as a real place but as a metaphorical concept. Proponents argue that the confusion stems from a simple mistranslation of Ur-Draconic texts. In this view, Draktharach is not a geographical location but the embodiment of draconic power itself: their divine mandate to claim territory, to rule, and to protect what is theirs. The word, therefore, is understood as a term for sovereign pride, not a physical mystery to be solved.

The most pervasive interpretation, however, and the one upon which most draconic religious traditions are based, is that Draktharach still exists but is merely hidden from sight, magically shielded to keep it truly protected from the lingering influence of the Netherhells. This belief, however, begs the question of why any dragons remain in the world. The common answer is that modern dragons are the descendants of exiles, banished from this paradise for various transgressions. This has given rise to countless spiritual traditions centered on "earning" one's way back into Draktharach, becoming worthy of entry. What, precisely, makes a dragon worthy has never received a unified answer, resulting in a fractured landscape of competing philosophies and religions across all of dragonkind.

The Crisis of Purpose

This uncertainty is tied to the concept of the dragons' original "divine purpose": to protect and guide the Firstborn Kin. A dragon's stance on this abandoned mandate reveals much about their worldview. Some, particularly those in Qor-Kalons that still venerate the Divine Parents, believe their purpose was never revoked. They hold that the Divine Parents will one day return and expect to find dragonkind still faithful to their charge. These dragons exhibit a rare benevolence towards kin, seeing themselves as dutiful custodians.

In stark contrast are the spurned, those who reject the Divine Parents entirely for what they see as a profound betrayal. Punished alongside the guilty, these dragons resent the kin for causing their fall from grace and often seek to reclaim their divine status through other means, including the worship of the New Gods.

The most common path, however, is for a dragon to reject the divine purpose completely and forge a new one of their own choosing. This drive to fill the existential void left by their abandoned mandate is the metaphysical origin of the famous draconic "hoarding" behavior. Unable to guard the kin, they instead dedicate their long lives to an obsession, be it an art, a craft, a field of knowledge, or a physical collection. The hoard, whether of objects, skills, or secrets, becomes their new purpose, a tangible meaning in a cosmos that has rejected them.

The Urdragon

Another profound question for dragonkind is the existence of the "urdragons." Across Netherdyn, archaeologists have unearthed the fossilized bones of dragons far larger than any modern species, some of a truly incomprehensible scale. A famous example is the town of Byeligrad at Wyrmrest in the Cursed Kingdom of Demenore, a settlement built entirely within the hollowed-out skull of an urdragon nicknamed "Balaur" by its inhabitants. It is difficult to imagine creatures of this size actually existing, let alone moving. While modern dragons are large, their average body length is between fourteen to twenty feet from snout to tail-base. The sheer scale of remains like Balaur suggests creatures of an entirely different magnitude. This lends credence to the theory that dragons were once far larger, or at least had the potential to grow to such sizes. Urdragons are thus thought of as the truest manifestation of draconic power and might, a potential that has somehow been lost between the Age of Paradise and today.

The mythos of the urdragon plays a vital role in draconic spiritualism and is often interwoven with the legend of Draktharach. One theory, for example, posits that the urdragon is the true form of dragonkind, and that modern dragons are but diminished shadows of their ancestors, their reduced size being part of the punishment for their banishment from Draktharach. A competing explanation suggests that dragons only grew this large and powerful in the direct presence of the Divine Parents, and that without their creators' light, each successive generation became smaller and weaker. The truth is obscured by the Age of Silence, a period of fractured history and completely contradictory records. As no one knows how long the Silence truly lasted, the number of millennia that lie between urdragons like Balaur and modern dragons is, at best, an educated guess. What is certain is that dragonkind suffered a great loss during that dark era, a loss of language, of history, and, in some undeniable way, of power.

This perceived decline has driven many dragons to an obsessive, life-long quest: to unlock the mystery of the urdragon and find a way to reverse this ancient diminution. By restoring dragonkind to its "purest form," they speculate, a new era would begin. An "Age of Dragons" would dawn, shattering the dominance of kin and re-establishing dragons as the rightful rulers of all Netherdyn.

Legal Status in Kin Society

Aside from the isolationist states of Galdorsmynd and Thaldrune, nearly all realms on the continent of Vespero — including Morvathia, Valleterna, Demenore, Dorcroix, and Anatara — are party to a trade agreement that honors this status. If one realm grants a species the Rights of Kin, the others are bound to respect it. Notably, however, at no point in recorded history has any signatory realm ever included dragons in this definition.

This exclusion means that despite their kin-level intelligence, ability to trade, and capacity to form complex societies, dragons can be legally hunted and killed. Furthermore, materials harvested from their bodies, such as dragon bones or scales, are legally allowed to be sold. While activist organizations like the Draconic Heritage Charity actively fight for the inclusion of dragons and a ban on dragon-harvested products, their numbers are low, and their protests have yet to sway the law in their favor.

Dragonkind itself has never made an organized push for equal rights. While some dragons have advocated for a unified society of kin and dragons, the majority of their kind seem to either not care or reject the entire concept as absurd. Many have no interest in being integrated into the larger communities of kin. Indeed, quite a few draconic communities believe that they should be the ones to rule and grant rights, not receive them from a "lesser" species. To them, accepting that the kings, queens, and elected councils of kin hold any authority over their kind is a ridiculous notion.

There is, however, an exception. While dragons as a species have not been granted the Rights of Kin, individual dragons have, in the past and present, gained a Special Right of Kin. This status can be granted to a singular entity, giving them legal protection without extending it to their entire species. It is usually temporary or connected to certain conditions. Dragons who have worked with kin as traders, mercenaries, or partners in some official capacity have often gained this special right to be protected under the law. A quite recent example is the Arcanum Dona Viperia, which granted this status to a dragon, permitting them to officially teach witchcraft to students within its faculty.

Wow! This is a beautiful article! The designs of your dragons are super wicked, the Dreamwraith is bad ass as all heck. And the world building is top notch, I especially love the end of how Dragons don't really care for having 'rights' given to them by the other kin. Good pride there!

Wanna see some good articles? Of course you do.

Showcase

Thank you! I am happy to hear you like the dragon designs. Over the last month I worked on a few for another project, and thought, for WorldEmber I put them all in a big ass lore article! :D

At the end of everything, hold onto anything.