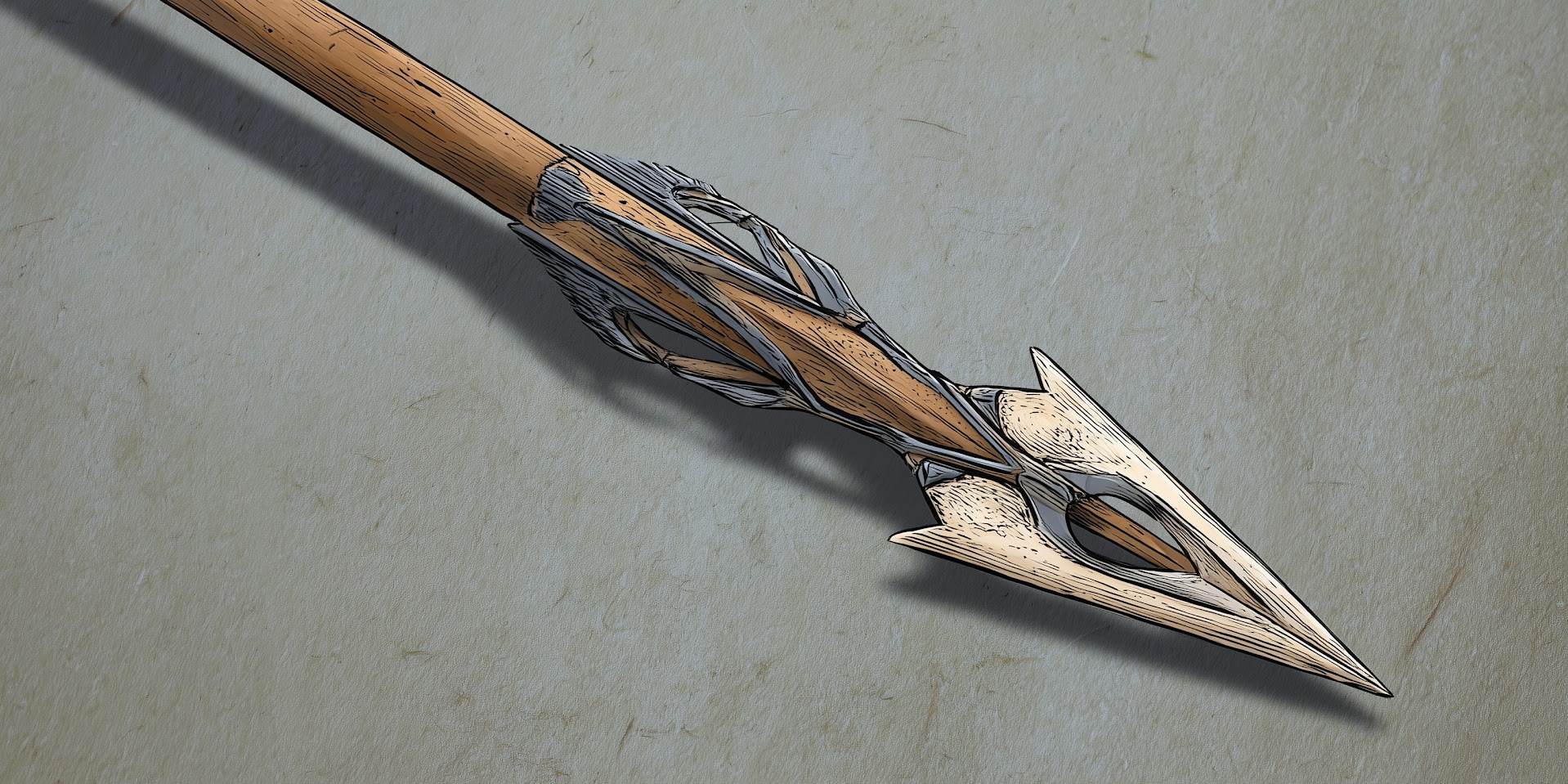

Singer Arrow

“The Singer Arrow doesn’t carry your voice. It carries your silence and understadning across the valley, hidden in the chorus of Spring.”

They do not look like much. Most are worn, stripped of paint, and kept in bundles apart from proper war shafts. They are rarely fletched for speed. They are not barbed. They are not balanced. They are not made to kill. Most are never even fired near another living thing. But for the Arin the Singer Arrow is a voice that never forgets how far it has to travel. The sound is sharp, brief, and unnatural. It rises mid flight, flutters on release, and ends in a chirp that never fades right. No animal makes that sound in Areeott. No wind catches that tone. If you are Arin you recognize it at once. If you are not it might pass you by. A strange birdcall. An echo in stone. A bit of metal in the wind. But to those who know what it is it is direction. Confirmation. A change in posture. A plan continuing without words. The idea is old. The shape is older. Some say it came from hunters who wanted to warn others without frightening game. Others say it came from the cliffs where shouting was death and signal fire could not pierce fog. The truth is it does not matter where it began. It is used because it works. And because in the mountains most other things do not. Singer Arrows are not unique to one family or warband. They are known across the high routes and low passes. Most Arin learn to recognize them before they understand their full use. A strange whistle in the trees. A high note in an open meadow. Then a change. Someone stands. Someone answers. And the child sees without speaking that something was said. Each arrow is tuned. Not in the sense of an instrument. In the sense of a key. The body is carved with small notches and hollows. The head is often blunt or hollowed to catch air. Some are wrapped in cord. Some have holes through the shaft. The pitch changes by design. The air sings differently depending on cut, grain, and pressure. Those who make them do not need plans. They know what sound they need and carve until it lives inside the wood. They are not used lightly. Nor are they sacred. They are tools. But they are deliberate. To hear one means something has changed. Arin groups do not fire them for practice. They fire them to communicate across terrain too large to cross or too quiet to shout. One call might mean stay. Another means move. A third means no path forward. They are simple, clean, and above all fast. What makes them powerful is not the sound. It is what the Arin have chosen to remember. A southern call means something different than a northern one. A call in winter carries a different tone than one in spring. Each group keeps its own rhythm. Some use single shots. Others fire two in sequence. You cannot read them unless you already belong. You cannot belong unless you already know. Outsiders sometimes try to copy them. The Avin campaign confiscated several and had them studied. They called them range whistles. Some believed they were part of a larger language. Others insisted they were magical. But in the end none of the decoded messages helped. Every sound had meaning only to the people who carved it. Outside that, the arrows said nothing at all. They are most often used when there is no time for caution. In avalanches. In hunts. In slow convergences across broken rock. One person fires. A ridge answers. A gap opens. A silence closes. The plan continues without pause. Arin groups can travel for days without speaking if they carry singers. They do not need commands. They only need awareness. Some of the older ones carry more than meaning. They carry memory. Songs taught by older kin. Calls that once belonged to a sibling, now passed. Some Arin keep broken singer heads tied to their packs not as tribute but as reference, to remember what call was used when that person was alive, to keep speaking the plan they left behind. They are not heirlooms. They are not named. Most are never kept more than a few seasons. They are carved in camp, reshaped in silence, adjusted with a knife or bit of cord. What matters is the sound. If the sound fades or cracks the arrow is discarded. It is not worth fixing. The tone must be clear. Even a small flaw means the message might go wrong. And when it goes wrong people die. The Arin do not treat that lightly. A false signal is not a mistake. It is a breach. If your arrow miscalls the pack you will not be trusted again. You will not be blamed aloud. You will not be punished. But the silence will close around you. The next time a signal is needed someone else will fire. And you will know why. They are not meant to impress. They are meant to reach. Their value is not in craft but in clarity. A well made singer arrow does not sing beautifully. It sings correctly. It sings once. It sings far. And when it lands the world shifts in response. No feathered shaft can do more than that. In most parts of the world arrows are for killing. In Areeott they are sometimes how you avoid having to. And when the silence is long and the plan needs only one note to continue the mountains listen for something familiar. Something light. Something fast. Something that says exactly what it needs to and nothing more.

Mechanics & Inner Workings

“Outsiders hear it once and think it’s a signal. It’s not. It’s a sentence. Pitched to a voice that only four others were taught to answer.”

Singer Arrows function by manipulating airflow during flight. When loosed, air passes over and through specific disruptions built into the arrow’s shaft, head, or fletching. These disruptions cause vibrations that produce sound. The result is not musical but deliberate, a sharp, strange call that carries clearly and unnaturally through terrain. The simplest method involves boring a small hole through the shaft, just behind the head or just ahead of the fletching. This hole interrupts the airflow, causing a short, high pitched whistle as the arrow flies. The angle, width, and placement of the hole all affect pitch. A shallow angle produces a dry warble. A sharper cut results in a thin, piercing trill. Some arrows use a hollowed head with a split or beveled edge. This creates a flute like effect, louder and harsher, suitable for windier or more open terrain. Others are made with slight splits in the shaft itself, bound loosely with cord so that air enters the crack during flight and rattles briefly. These tend to produce lower, throatier tones that carry better in forested environments. Fletching can also be shaped to alter sound. Some arrows use deliberately uneven feathers or bind the vanes asymmetrically to induce flutter. This does not produce the main tone, but it adds a signature pattern to the arrow’s passage, recognizable to those trained to listen for it. The tone produced is not consistent across all arrows. There is no universal standard. What matters is that each arrow is tuned to produce a specific pitch and that its intended listeners recognize that pitch instantly. Arin groups often create their own sets of tonal patterns. A call that means “wait” to one circle might mean “advance” to another. That variation is deliberate. If intercepted, the arrows say nothing intelligible to those outside the group. Most Singer Arrows are not recovered. They are fired in one direction, from one elevation, in one moment. Their message exists only in that flight. After landing, they are discarded or left where they fall. Occasionally one is retrieved and reshaped for another tone, but this is uncommon. Once their pitch becomes unreliable, they are broken. Unlike the Shriek Whistle, Singer Arrows do not require force or coordination to activate. They are not meant to carry emotion or mimic fear. Their utility lies in consistency. If the arrow is made correctly and loosed at full draw, the sound will follow. That is all that matters. The message is not in the beauty of the sound but in its timing.

Manufacturing process

“It is not the arrow that confirms. It is the shape of the silence that follows it.”

Singer Arrows are made by hand. They are not produced in workshops or bought in bundles. Each one is shaped by the person who intends to use it or by someone who already understands the voice it is meant to carry. There is no formal pattern. There are only results. If the sound works, the arrow is finished. Most begin with a regular shaft. Seasoned wood is preferred, straight and light. Some makers use reed or hollowed cane. Others use older shafts from arrows that no longer hold edge or balance. The point is not flight speed or penetration. The only requirement is that the shaft hold shape in the air and respond predictably to the carved modifications. The first step is determining the tone. This is not written down. It is remembered. The maker knows what sound they want, whether sharp, fluttering, split, or low, and begins carving toward it. A small hole may be bored just behind the head. A hollow may be cut into the shaft. The notch may be widened, narrowed, or given a beveled lip. All of these affect the way air passes and splits when loosed. Once the basic structure is shaped, the maker draws it with no head attached and listens. If there is no sound, the hole is widened, deepened, or repositioned. If the sound cracks or skips, the arrow is abandoned or used for scrap. If the sound flattens in flight, the fletching may be shifted or the shaft lightly warped to introduce resistance. It is trial and error, tuned by experience. Most arrows are finished in less than a day. They are not meant to be permanent. Cord may be wrapped loosely near the tip to shape the airflow. Fletching is often mismatched on purpose, with one vane slightly longer or set at a sharper pitch to affect spin. Glue is used sparingly. The arrow must hold together in flight, but there is no need for durability beyond that. If the arrow passes the maker’s final test, producing a clean tone on full draw, it is marked and kept. Some score a small groove near the nock. Others tie a single colored thread. Most use no mark at all, simply recognizing it by sight or touch. It is stored apart from hunting or war arrows, kept dry, and only fired when there is a message to send. No two arrows are identical. Even among those made by the same hand, each one carries a slightly different voice. That variance is not a flaw. It is part of how meaning is built. The person hearing it knows not just the tone but the feel of who carved it. That recognition carries weight. When the arrow is no longer clear, when wind distorts its cry or weather weakens the shaft, it is snapped and burned. Not with ceremony, just with finality. The sound it once made is gone. Another will be made when it is needed. The mountain does not keep echoes. Neither do the Arin.

History

“As though the night had not been filled with enough horrors. One moment, our guide was sitting with us next to the fire in silence, then came a strange bird call, and our guide sprang to his feet like his mother just called his name. He fired an arrow into the air, off into the same direction from which the sound had come across the valley, and which made a similarly curious birdcall. He ordered us to take shelter as a storm was approaching. One hour later we were consumed by a blizzard that lasted an entire day."

No one remembers the first person who carved a Singer Arrow. That detail is not passed down. It may have been a hunter, trying to reach a partner without spooking the herd. It may have been a child, carving into a blunt shaft without knowing why. Whatever its origin, it did not begin as strategy. It began as sound, carried farther than expected, and understood without being explained. The earliest surviving fragments show up not in war records, but in household inventories. Hunting kits. Tool caches. Marked only as “signal arrow” or “windcaller.” They were not rare. They were not treated as weapons. They were used in the same way a person might use smoke, or stacked stones, or folded bark. As signs. As simple confirmations of location. As shared breath between those who could not yet see each other. It wasn’t until the border conflicts that the arrows took on more serious meaning. In the narrow ridges above the passes, shouting was suicide. Drums could not carry through snow. Smoke was useless in fog. But a single Singer Arrow, fired from slope to slope, could pass instructions clearly and instantly. It didn’t matter who else heard it. Only those it was meant for would understand. Over time, groups began shaping their own sets. Some used hollow shafts. Others twisted the head. Some left feathers stripped. The sound changed with every alteration, and soon the arrows carried more than presence. They carried intention. To a stranger, they all sounded alike. But to the people on the ridge, a half-second trill could mean to wait. A snap could mean to close. A short warble could mean to pull back before anyone was seen. In Arin memory, they are not spoken of with pride. There are no ballads about them. No one recites the history of this practice aloud. It is not considered an art. It is not taught by rank. It is simply passed along. A gesture shown in camp. A sound demonstrated in the quiet. A person saying, without words, that this is how we speak when we cannot speak. The arrows never disappeared. Even in peacetime, they remained. Used in hunting. Used in long walks. Used to pass between ridges when the sky turned black or when animals scattered without cause. They are not stored in armories. They are not locked away. They travel with those who move. And when they are needed, they are used the same as always, once, without hesitation. Their meaning has never expanded. They are not used for ceremony. They are not carved for aesthetics. No great innovations have been made. Some newer makers have tried to add tail chimes or colored binding. These are stripped away. The only thing that matters is the sound. And whether the people who need to hear it can still tell what it means. Among the oldest clans, it is said that the arrows came from the land itself. That the mountains cannot speak, but they can carry voices. That the air between peaks listens more carefully than the sky above. Whether or not this is true does not matter. The arrows are fired, and the land replies by remaining still. That is enough.

Significance

“Our oldest story is two cousins hunting across a fog vale. One arrow sang. One cousin moved. That’s the whole tale. That’s the whole lesson.”

The Singer Arrow does not represent status. It does not mark rank. It is not given to prove worth or passed down in ritual. Its value lies entirely in what it allows others to do without being seen. That alone is enough to grant it a permanent place in the mind of every Arin who has ever needed to signal across distance. It is not carried into battle to be seen. It is carried so others do not need to be spoken to aloud. In tight terrain, in wind, in whiteout, in a moment where one wrong movement could be seen from above, it is the arrow that speaks. No weapon, no runner, no shouted command could reach faster. That makes it one of the few tools no one leaves behind. Children learn its call before they are taught to shoot. Most will hear it fired before they understand what it means. But they will watch their elders react to the sound. They will see someone stand or shift or move in reply. And they will learn, even without words, that something has changed. That is the lesson that matters. Not what the sound means, but that it means something, and it means it now. The arrows are not shown off. They are not collected. They are not displayed on walls. They are shaped, used, and replaced when they fail. Their value is not in their appearance but in their timing. A Singer Arrow fired too late is as useless as a message never sent. The weight of their use is measured entirely by whether the person they were meant for was able to move before something arrived. Some families shape them in pairs. Some shape them in silence. Some sing while carving. Some do not. There is no universal ritual, but there is universal intent. If you carry a Singer Arrow you are trusted to know when to use it and more importantly when not to. The consequences of misuse are not public. They do not need to be. No one wants to be the reason a call went wrong. There are those who claim that to hear one and not respond is a kind of abandonment. Not because of the call itself but because of who fired it. To be within earshot and not move is to break the thread. It means either the bond has failed or the person it reached is no longer able to act. Either outcome carries its own weight. In the high country, where voices fall short and paths shift without warning, the Singer Arrow is not a tradition. It is not a symbol. It is a continuation. It says clearly and without ornament, “We are still here.” It does not ask for attention. It does not wait for permission. It arrives, and those who know it do not hesitate. That is its only honor. Not in history or carving or praise. But in the moment it passes overhead and the world beneath it shifts because someone knew exactly what to do next.

Item type

Ammunition

Current Location

Manufacturer

Related ethnicities

Owning Organization

Rarity

Uncommon

Weight

1.5 oz

Dimensions

28 to 32 in

Base Price

3 - 5 sp

“When they fired, I didn’t flinch. I just turned and walked. Like they’d tapped my shoulder from a thousand yards away.”

Comments