Body types and sub-types

Among dragons, there is a massive amount of variation in their anatomy and morphology, with several recognized sub-types within the species. The vast majority of these morphological differences are accredited to the recent hybridization of now extinct species to form the modern species of Draconis draconis, similarly to hybridization that occurred between different closely related hominins. Dragons are commonly categorized based on collections of common anatomical morphs with similar features, although most individuals will typically place somewhere between two or more morph types.

Biped

Biped type dragons are as the name suggests, dragons that primarily use their hind legs for ground based locomotion. The biped type has two main types, the true biped, and wyvern type. Both have their own unique features, but share more traits in common with one another than other body types found in dragons such as smaller heads, reduced forelimbs, longer necks, and typically lighter frames. It is quite common for biped type dragons to have a reduced number of toes on their hind limbs, commonly only having 2-4 toes on each foot. It is also common in biped dragons for at least one toe, especially in three-toed individuals, to be 'reversed' or hypermobile.

True biped

Often simplified to simply the biped type, dragons with this body morph have much longer and stronger hind limbs that proportionally, are significantly larger than their front legs. The front limbs generally are rarely if ever used for locomotion, instead primarily being used for object manipulation, grooming, and grappling of prey. Almost all biped type dragons cannot pronate their front 'hands', which typically have more fingers than their rear feet and are much more nimble. Typically, the front hands and limbs are oftentimes much weaker and favor dexterity and speed over strength. While true biped dragons can utilize their wings for ground based locomotion, it is not common, and typically biped type dragons will only use their wings on the ground for balance or aid when standing from a lying position.

Neia Lun De Draco is an example of the true biped body type.

Wyvern type

Wyvern type, or wyverns, are dragons of the biped type that do not use their front legs for ground based locomotion, but instead utilize their wings. All wyvern type dragons have hypermobile shoulder joints in their wings and typically have much larger chests, allowing their wings to more easily reach the ground, as well as significantly larger wing wrists with heavy padding.

Ahkora the Sanguine is an example of the wyvern type.

Quadruped

As the name suggests, all quadruped dragons walk on four legs carried underneath their bodies. Generally, the front and back limbs are relatively in proportion with one another and of similar sizes, though the front legs are typically more mobile. Within quad-type dragons, males commonly have an extra digit on the front feet called a spur. This spur is highly mobile, strong, and allows for extra dexterity in grappling prey and rivals. Most quad-type dragons are rather slender, often described as 'feline' in their movement and general anatomy. Wings are typically quite robust and large, with proportionally smaller wing spurs than biped type dragons, but still mobile enough to be used for some limited grappling or object manipulation.

Pharhund is an example of a quad type dragon.

Heavy Type

This body type is almost exclusively found in quadrupedal dragons. Heavy or robust type dragons will almost always grow to significantly larger sizes than other dragons of similar diet and age, with distinctly larger heads, more robust legs, and oftentimes larger wings and tails than their counterparts. With significantly larger muscle mass and higher bite forces, robust type dragons are truly capable apex predators that oftentimes feed exclusively on megafauna in their adult age, with a higher proportion of this subtype feeding on other dragons. Dragons of this body type also often see different behavior patterns than other dragons, as they more commonly have an easier time fending off rivals due to their size, and are more likely to form large harems and defend much larger territories.

Serpentinian is an example of a heavy type dragon.

Heavy type B

Also known as the hypo-heavy type, this morph of dragon is thought to primarily be caused by an imbalance of growth hormones or pituitary gland deformations, though more research is needed. As a sub-type of the heavy or robust type, these dragons share many similar traits, however, type b heavy dragons oftentimes display them to the extremes. They will grow significantly faster than their peers with even more exaggerated features such as extremely muscled necks, chests, legs, and tails, extremely robust heads, and powerful wings. These features typically do not scale entirely throughout a heavy type-b dragon's life, as the vast majority will grow disproportionately, oftentimes outgrowing their wings and with an eventual taper in their growth, leading to flightlessness. The heads of type b dragons will also oftentimes see a similar taper in growth when compared to the body.

Aien Sol De Draco is an example of the Type-B body type. Batterion is commonly believed to be the earliest example of a heavy type-B dragon, and lends credence to the theory that the trait was not one found in any ancestor species, but individualistic variation or mutation that can occur in any dragon, not just quad types.

Antegument

The antegument, or skin covering, of dragons can vary from individual to individual as well as which section of the body it is found. Nearly all dragons will have at least one segment of the body covered by scales, but this varies depending on bloodline and ancestry. Even in the most feathered dragons, some scale covering remains, most commonly on the lower abdomen, feet, and around the eyes.

Scales

Scales are the most common antegument found in dragons, with multiple different variations. The most common scale type, found in the majority of dragons, is the 'microscale'. Microscales are incredibly small, uniform in size and shape, and oftentimes quite thin and more akin to skin. Microscales are common in sensitive or highly mobile areas such as around the eyes, joints, toes, corners of the mouth, and other delicate parts of the body.

Keeled or serpent scales are much larger distinct areas of interlocking scales commonly found on a dragon's limbs, tail, neck, and spine. Keeled scales do not typically cover the whole body, and are instead found in areas that are likely to suffer damage from hunting or rivals. These scales offer a high degree of protection and are less easily bent, instead typically cracking or shattering when damage is caused, such as a bite or claw wound.

Plates

Plates are almost always in isolated patches on the neck and spine of a dragon, and are more commonly associated with the heavy type b body type. Plates typically do not grow until subadulthood, becoming fully fused in adulthood, and are made up of keel type scales that have grown together. With extremely poor flexibility, high rigidity, and being extremely thick compared to other scale types, it is not uncommon for plates to 'peel' up over time and interlock, allowing a dragon to move freely while not sacrificing protection. it is believed that the gene causing plate type scales and osteoderms is the same, but triggered by different hormonal or environmental factors.

Osteoderms

Similarly to plates, osteoderms are not an antegument that covers the entire body, but is instead found in isolated patches, most commonly along the neck or spine. By subadulthood, osteoderms will begin to calcify into rigid bone, offering extreme protection from wounds.

'Feathers'

Feathers in dragons are not true feathers, as are found in birds, but rather, more similar in structure to protofeathers or 'dino fuzz'. Generally, these are long downy structures that remain soft and pliable, more akin to fur than a flight feather. This skin covering is most common along the back, chest, and spine, but can also cover nearly the entire body in some individuals. Almost all members of the

Lunar Dragonflight will have a near complete body covering in feathers, though those sired by

Aien Sol De Draco tend to favor a scaled body.

Different variations of the feathered body exist. Many dragons will have short and sleek feathers that protect the body from the sun, rather than for warmth, with longer sections along the spine and neck. Lunar dragonflight dragons oftentimes have much longer feathering that can be incredibly dense and is oftentimes more akin to fur than it is a feather in structure, with few branches and instead, is more spindled in structure. Dragon feathers being a modified scale have a rough texture, often described as being similar to fiberglass or wire wool.

Sexual Dimorphism

Dragons do not express a high amount of sexual dimorphism over all, with most sexual dimorphic traits being rather subtle, coloration, or caused by behavior such as scarification.

Spurs

Male dragons, especially of the quad body type, commonly have a spur claw on their inner wrist of the front legs. These spur claws are massive in proportion to their other claws, oftentimes being up to double the size and supported by a large and powerful extra toe. Spur claws are also commonly recurved and when at rest, held so that they do not touch the ground when walking, and must be flexed in order to be extended. The most common use of the spur is in intraspecific combat, likely hailing from a time prior to the development of the gender culture now found in dragons. Male dragons can also use the spur akin to a thumb due to its high dexterity and range of motion, though this is uncommon. The spur will generally be present from borth, but not grow to be a useful appendage until sexual maturity.

Curiously, the spur can be be present in female dragons as well, although it is much more rare and almost always smaller than that of male counterparts. Dragons that are female at birth and undergo treatment may also develop a spur claw with repeated treatments, and the spur also oftentimes appears to be a point of dysphoria for many dragons, with products meant to emulate or exaggerate the spur claw being quite common.

Skin Flushing

Another trait almost exclusively found in male dragons is the ability to flush the face, throat, and occasionally parts of the wings with blood. Skin and scales in these regions are commonly much thinner than in females, allowing expanded blood vessels to tint the area when properly flexed. Flushing these areas of skin with blood causes them to become red, pink, or purple in hue.

Sexually Mature Traits

Patterning typically changes significantly over the course of a dragon's life, with most having distinct juvenile patterns until subadulthood. Typically, juvenile patterning consists of spotting down the back and tail, with distinct eye spot patterns on the wings. Eye spots in particular are often seen as the mark of an immature dragon, as most large individuals will lose this pattern around 20 years old.

Dragons that are sexually mature will display exaggerated featured compared to younger members of their species. Most often, these are traits considered to be highly desirable, such as long horns, spines, or quills, thickened scales on the face and neck, and bright colors on the face and neck. These features will almost always grow larger as a dragon reaches adulthood, typically reaching their full size and shape around 30-40 years of age.

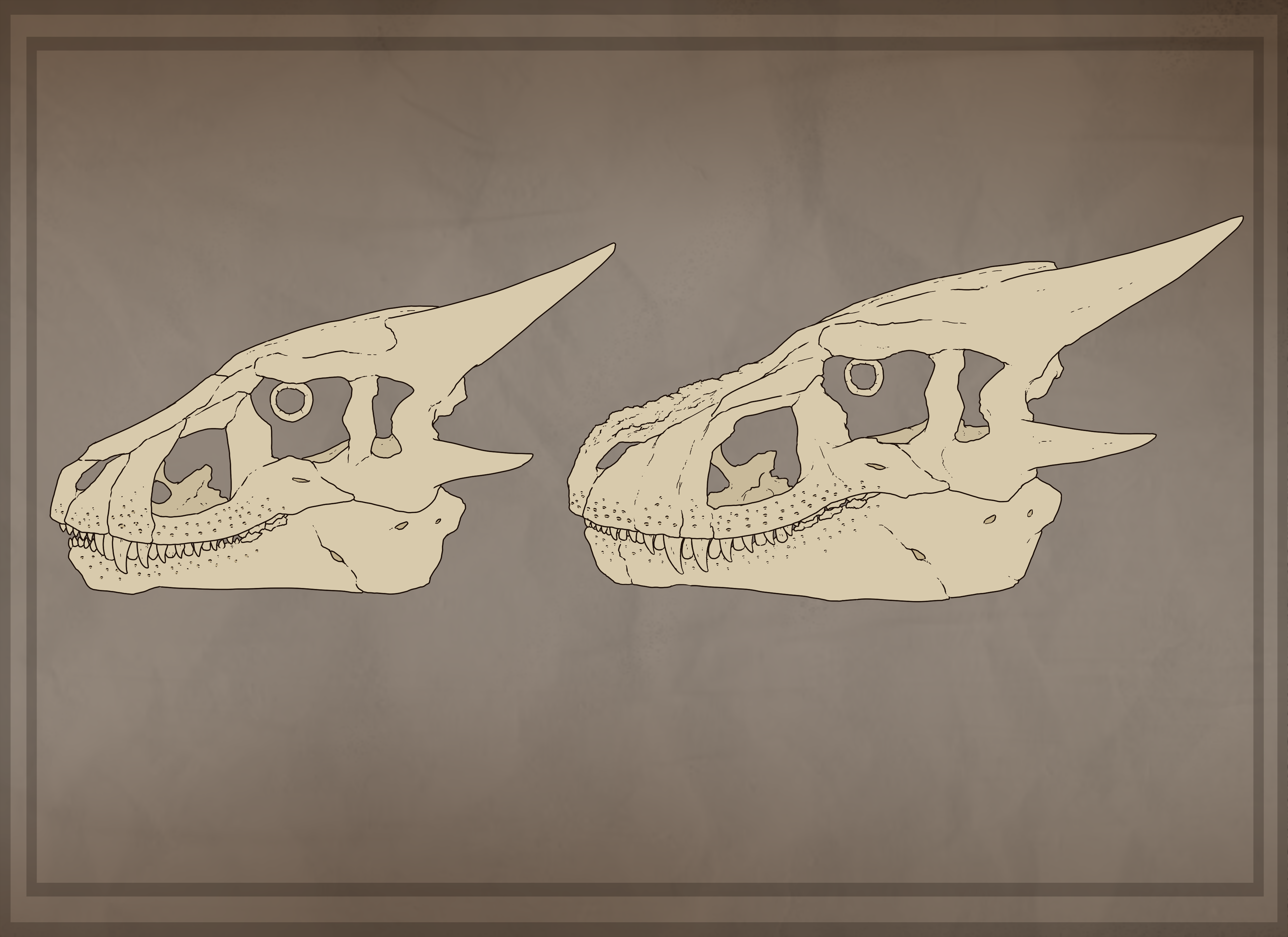

Head and Skull

Present in all dragons are an array of small foramen that are most commonly attributed to being nerve pits- small holes allowing nerves to pass through the bone, giving dragons extraordinarily sensitive snouts and jaws. This array is present even in the most ancient of specimens, though prehistoric dragons oftentimes have these structures alongside much larger hollows and foramen that are believed to have once housed venom glands.

The skulls of dragons notably change significantly as they age. Dragons typically will reach adult size around 40 years of age, but will still have many distinct growth plates in their skulls, particularly around the fenestre, orbit, maxilla, and premaxilla. These plates are only partially fused, and will typically only fuse later in adulthood after several periods of growth triggered by excessive food (See Section: Organs, Digestive System.).

Older dragons have much more robust skulls with thicker struts and more fusions to surrounding growth plates. The sagittal crest, which is typically not prominent in dragons, will also oftentimes grow larger and more robust in older individuals who have had more growth periods triggered, allowing for more and stronger connections of jaw muscles. Similarly, the lower jaw will oftentimes grow much larger particularly in the mandibular to allow for increased bite force, oftentimes changing shape to a convex bow.

Another feature commonly found in the skull of older dragons are nasal deformations. The premaxilla, after having fused with the nasals and lacrimal parts of the skull will oftentimes grow a rough thickened texture that is commonly associated with scar tissues or the growth of a boss on the face. This development is by far more common in stags, who often make use of scarification for attracting mates and intimidating rivals, and is thought to primarily be a response due to repeated damage to the bone. This growth can also continue onto the lacrimal, preorbital, and jugals, though is ordinarily contained to the premaxilla and nasal. Very rarely it has been observed as growing on the sagittal crest, and in individuals with this much growth of the nasal deformation, there is a higher observed rate of bone and skin cancer.

Organs

Respiratory and air sacks

Throughout a dragon's body and bones, but most prominently in the chest, neck, and pelvic region, are a series of air sacks. These organs are a part of the respiratory system and connected to the lungs, assisting with breathing and reducing weight. Similar systems are commonly found in pterosaurs and dinosaurs, and thought to be of similar origin and purpose. Air sacks, similarly to the lungs, can process air breathed in to oxygenate the blood, but are not as efficient, likely leading to favoring an increased number of the organs. The air sacks are also a large component in vocalizations, allowing dragons to produce low thrumming notes, rumbles, and grumbles.

Damage to the air sacks and lungs can be deadly to dragons, as can a respiratory infection. Damage or illness to either the lungs or air sacks alone causes a significant drop in blood oxygenation that can cause dangerous levels of carbon dioxide to build in the blood, difficulty breathing, or in serious cases, death by asphyxiation.

Digestive system

Present in all dragons is a dual chambered stomach that is commonly divided into the 'true' stomach and the gas chamber. The true stomach is where the bulk of digestion occurs prior to the intestines, with a valve connecting the gas chamber. The gasses produced by the stomach during digestion filter into the gas chamber and are collected for use in creating flame. Due to being a highly flexible membrane, gas chambers can expand to many times their deflated size, storing large quantities of flammable gasses from the gut. This chamber is connected to the 'gas throat', which runs parallel but not connected to the esophagus.

Dragons have a unique microbiome in their stomachs and intestines, favoring bacteria that produces large quantities of gasses like methane during digestion. Paired with extremely strong stomach acid, dragons are able to digest even quite tough tissues such as ligaments, tendons, hoof and horn, and even bone. A dragon's stomach is highly flexible and more adapted to infrequent but larger meals, and able to adapt to the circumstances of their environment. During plentiful hunting seasons, their metabolism increases for much faster digestion and prioritizes storing energy as fat in the tail and abdomen. Extreme periods of plentiful food are known to trigger growth phases even in adult dragons, causing them to continue growing larger than they would ordinarily. During lean times, metabolism slows in order to conserve energy.

Much of this process is involuntary and triggered by food quantities, in part being adaptation to seasonal changes, as all dragons will typically feed more frequently during wet seasons, spring, or summer than they will in the dry or winter seasons. It can, to a degree, be controlled voluntarily, as dragons with the means may hunt or purchase excess food if they wish to attain a larger size. Following multiple growth periods in adulthood, hormones released by the stomach, adrenal gland, and pancreas will generally cause further excesses of food to instead trigger a different growth phase, where instead of increasing body size, the dragon's body will begin to fuse growth plates, thicken bone, and prioritize muscle growth. This is thought to happen due to repeated cycles of plenty and lean hunting periods, where a dragon can no longer sustain continued growth to larger and larger sizes, where their body will put a cap on their growth in order to prevent outstripping their own resources. In many of the oldest individuals, this hormone response appears absent or diminished.

Reproductive system

Dragons have two distinct sexes, male and female. Outside of their reproductive anatomy, dragons typically have little sexual dimorphism, with the common differences typically being that males may have a spur claw on their front feet, slightly larger horns, and are able to flush their necks and faces with blood.

Female dragons produce eggs from a single ovary located in the abdomen, generally just in front of the pelvic boot. Typically, dragons can produce eggs throughout the year when in optimal conditions and when food is plentiful, but the vast majority will only do so in the early spring and fall. Female dragons must mate with a male in order to produce eggs, and any ovums produced without mating will be reabsorbed by the female. In preparation for breeding, female dragons will develop medullary bone in their legs, wings, and horn cores. Medullary bone is used to store calcium and other minerals crucial to egg production, and generally reabsorbed following a reproductive cycle.

Typically, between 6-12 ovums are fertilized, but it is most common for only 4-9 to develop into fertilized eggs. This number is variable, as larger females will typically produce more and also larger eggs. Larger eggs are generally associated with larger birth sizes of hatchlings that typically have far fewer predators in youth and grow to adult size faster.

Awesome work love the different varieties of Dragons you have created