Golden Noodles

Traditional? Yes, of course the noodles are traditional! The lerind ari navori would never cook them in traditional dishes if they were not!

It is a testament to the expertise of our culinary ancestors, how delicious and versatile the noodles are.

Golden Noodles:

All artwork by Shade Melodique

unless otherwise stated

Brief Comment About Catak:

unless otherwise stated

Mara'ki and Jila

The aki, upon reaching the lands south of the Sea of Condioh, searched for a replacement for the ground blueroot paste from which their bread was made. Their new home did not have blueroot or any of its grainy kin. The search led cooks to try a vast variety of new plants--some good, some bad, some deadly--but none made its way into meals as a staple until Mara'ki, a toothless great-grandmother, first tasted esapan noodles. Mara'ki, being without teeth, had a difficult time chewing. The fake milkshell teeth set she owned hurt her gums and never stayed in place, and she despised wearing them. She also despised the soups and other liquids she imbibed, as she wished to tear through a good steak or crusty bread now and then. But gnawing on small pieces before swallowing them mostly whole did not satisfy her craving to eat something with body.

She grumbled about her problem to her neighbor, Jila, who hailed from an eastern Seari people called the Barik Fena, or Green Fingers. They grew crops on the mountain slopes that fed the grassland herder peoples, and their abundant harvests were admired along the coast. Because of her farm upbringing, Jila had a solution: golden esapan noodles.

Golden esapan noodles? Mara'ki had never heard of them.

Jila explained that the farms in the area grew a grain called esapan, and they ground the golden variety into flour to make thin noodles. The noodles, while bland, could fill the mouth for a good chew, but were soft enough for Mara'ki to eat without scratching up her gums.

Skeptical, Mara'ki accepted a dinner invitation to try them.

And she loved them!

They filled her mouth, and she could chew to her heart's content while they melted on her tongue. The only problem was, while they had a hint of sweetness, they were otherwise bland. She could fix that.

The aki tended to prefer spicy meals, and had brought a variety of spice plants and peppers south with them. She used what she already had, mixing two earthy spices with sweeter herbs to create what she called tongue-twitching good. A bit too spicy for her friend Jila, but Mara'ki thought it perfect.

She shared her and Jila's new dish with others, who added their own flavorings, and both the aki and the Barik Fena latched onto the new dish.

The aki used the flour to make bread, but it never had the popularity of the noodles, which only required water (or egg if you were fancy) and esapan flour, then a pot of boiling water to cook them. Within a few years, every table within echo distance of Mara'ki and Jila had noodles of some sort along with their nightly meal. The easy-to-make flavored noodles replaced bread as a staple in many households.

Popularity

From there, the dish spread throughout the eastern seaboard, and more people than the grassland herders bought esapan flour. The Barik Fena expanded golden esapan farms along with the demand, which kept prices stable and low. The ease in which one could make the noodles--mix flour with water, flatten and cut into strips, then boil--made it a convenient food for all castes. An enterprising Barik Fena Greenroot practitioner dried the esapan noodles to preserve them for food experiments, but it took her daughter, Relle, to realize the trade potential. Dry noodles could reach markets in vastly farther places, unlike the flour, which often met its end by mold, insects or vermin.

Relle offered a service to dry the noodles for interested traders. The Barik Fena immediately latched onto the new way to ship whole noodles rather than just the flour, and the cheap foodstuffs filled inland markets.

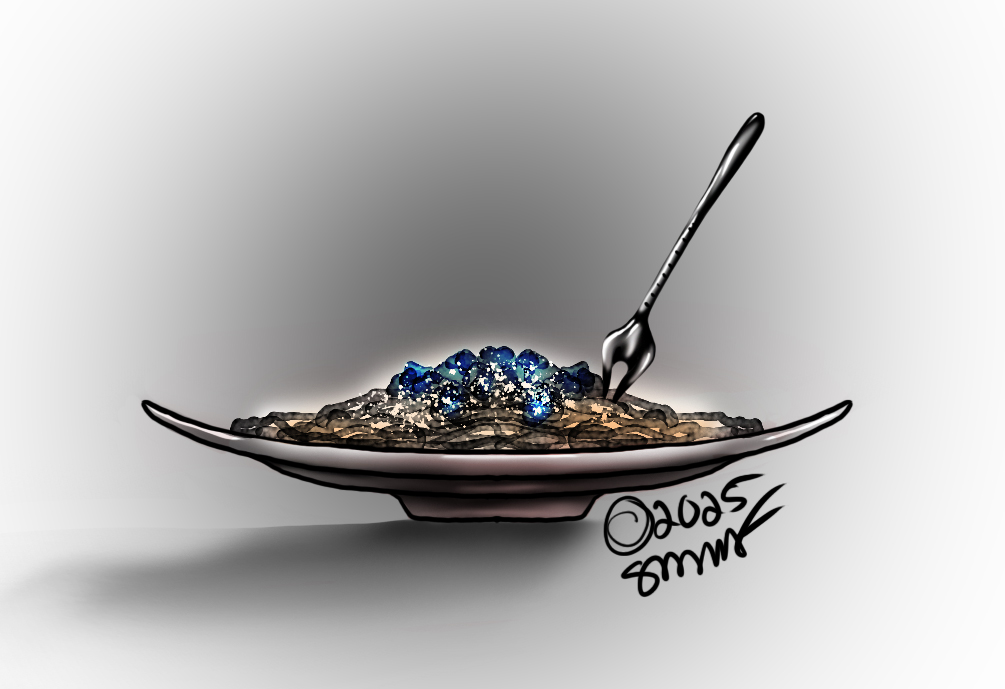

Traders also sold the spices, seasonings and forks used to create and eat the noodles. Some enterprising merchant must have told customers they needed the special forks (two-pronged, with a dip in the middle like a spoon) to eat the noodles, because a brisk trade in them ensued.

Gold-plated ones became collectors items, and wealthier households purchased several as a way to brag on their riches.

The aki shared recipes with clan-kin and clan-kith further from the seaboard, and more than just spices joined the noodles; meat, sauces, vegetables, fruits and more began to top them, making them into a full meal rather than a side dish like bread. Within a generation, esapan became a staple within aki homes. At this time, people started asking for the golden noodles in taverns, eateries, and high-end dining establishments.

Cooks played with color as well as flavor and toppings, with blue-tinged fish cubes on the golden noodles becoming the favorite look and taste. The aki preferred fish to other meats, and because the bland esapan could work with anything caught, revered traditional cooks tasked with upholding aki legacy recipes quietly added them to their repertoire.

To better pretend that they were traditional in origin, they called them golden noodles rather than esapan. It took another generation before the idea of the food being traditional stuck, and ever since, golden noodles, whether as a side dish, a meal, or a dessert, have graced the dinner tables of the aki.

Comments