The Werewolf

Without conceit, I regard it as self-evident that my research has shed a scientific light into many dark corners once relegated to the domain of the supernatural. But despite the many avenues down which my research has led me, few can compare to the horrors I present to you today - of the human body cruelly twisted into a canine form so animalistic, it shocks the senses.

Throughout history, tales and legends of dog-men appear in nearly every culture in the world. From the cursed lycan of ancient Greece to the widespread werewolves and cynocephali of medieval Europe, to the rougarou of Cajun folklore, and even to the modern sightings of creatures such as the alleged Beast of Bray Road. What I present to you today, my valued reader, however unbelievable it may seem, is that each of these accounts is rooted in some level of truth. A primal fear seated deep in humanity's subconscious, and one that I believe can be traced to mankind's first contact with a devastating virus I have named the Lycanthropic Parvovirus.

But before we move into the details of this microscopic horror, permit me to provide some context for the work that led to its discovery. As I previously alluded, for decades my own research forged a path that may have never intersected with this particular virus. But then, nearly by chance, I met a brilliant biologist equally passionate and similarly motivated to uncover truths that mainstream academia refused to entertain.

Sadly, though we were able to trade ideas for a time, the thread of fate that had pulled us together was tragically and very suddenly severed. This scientist, whose name, at least for now, will remain anonymous lest her legacy be tarnished, was killed by the very organisms she studied. I found her in her home, her body rent to pieces. Even still, her research became the foundation of my own, though most was gleaned from the pages of the detailed journals she left behind.

Although I am grateful for her notes and our brief time together, the findings that were her life's work have become a heavy burden. The light of science at its core is a wondrous form of systematic discovery. But I sometimes wonder if, perhaps, some things are best left in the dark.

The Lycanthropic Parvovirus

As you likely know by now, my own work has led to the momentous, though as yet largely unaccepted, discoveries of the Human Vampiric Virus and the Human Zombic Virus. Both appear to be members of Mononegavirales and each, through a cascade of genetic alterations, transforms their hosts into violent killing machines, though in very different ways.

But in terms of morphological restructuring, neither of these viruses can compare to the Lycanthropic Parvovirus, which eventually causes such drastic changes in its hosts that they can scarcely be recognized as having once been human.

At the risk of pressing your gracious allowance, I will now move on into the second part of my presentation - the virus itself. As the name indicates, LPV is classified in the family Parvoviridae. In general, parvoviruses are capable of infecting numerous species, though most people are familiar with the canine and feline strains, which cause severe and life-threatening diseases in wild animals and pets alike. In humans, parvoviruses are much less severe, frequently causing no symptoms whatsoever.

What makes LPV unique is that it is zoonotic, easily transmitted to humans via the bite of an infected canine - specifically, in nearly every case, it's the bite of a Canis lupus, a gray wolf, or one of its many subspecies. Indeed, this virus appears to be highly specialized, unable to infect or be carried by any organisms except for canines and primates.

As a result, the most common victims of lycanthropy, or "lycans" as I call them, are those whose professions bring them into frequent contact with wolves, such as hunters, trappers, and lumberjacks.

Viral Mechanism

Upon entering a host's bloodstream, rather than targeting a single type of tissue, the Lycanthropic Parvovirus proceeds to infect and, on some level, transform every living cell with a nucleus in the body. Most parvoviruses enter host cells by endocytosis, traveling to the nucleus where they wait until the cell enters its replication stage.

Only then is the virus's genome uncoated and replicated, at which point the virus's messenger RNA is transcribed and translated. Eventually, mature virions exit the host cell via lysis, or destruction of the host cell.

But the Lycanthropic Parvovirus appears to utilize a much stealthier method of reproduction. Rather than destroying the host cell, which the body could associate with inflammation, thereby alerting the immune system of its presence, the new virions bud from the host cell, leaving it intact, though altered.

In this regard, LPV is perhaps more similar to Human Papillomavirus, which is a similar non-enveloped DNA virus that alters cellular genomes without destroying the cell itself. In fact, because LPV does appear to be a DNA virus, rather than RNA as with the previously described HVV and HZV, no reverse transcription from RNA to DNA is necessary. Upon entering a cell, the viral DNA can immediately integrate itself into the host's chromosomes.

Symptoms and Transformation

In short, the changes that Lycanthropic Parvovirus makes to its host cells are drastic and rapid. In my studies, I have observed that the onset of symptoms occurs at roughly 24 hours from the point of infection.

These symptoms are somewhat generic hallmarks of an extreme immune response - severe thirst, high fever, chills, and even itching, the latter of which is likely related to metabolic increase brought on by the virus. These are similar to the other diseases I have presented, but unlike HVV and HZV, the Lycanthropic Parvovirus appears to have no need of a coma to facilitate the transformation of its host.

By the 48-hour mark, the fever begins to dissipate, and the other symptoms are drastically reduced. However, new symptoms rapidly begin to take their place. Extremely rapid hair growth becomes apparent, and the victim becomes increasingly violent.

Communication with the victim becomes nearly impossible, as their responses degrade into grunts, growls, and hisses. Attempts to restrain patients at this stage often result in self-harm and even more extreme aggression. Indeed, the victim will take great efforts to flee from the company of any humans, presumably to complete their transformation in a more secluded area.

But now, I must warn you, even if you regard my previous work as truthful, the transformation that follows LPV infection is so radical, the contortions it places upon the body so disturbing that even in recounting it here, I scarcely believe it myself. The transformation from the humanoid body plan to that of a lycan is drastic, and even to the scientifically-minded, disturbing. Indeed, few could look upon the lycan's distorted visage without having to stifle a sense of fear and repulsion that rises from the id like a dormant memory.

Transformation Process

However, in stark contrast to the portrayals in movies, novels, and even folklore, this transformation does not wait for a full moon, and it takes far longer than mere hours to complete.

Approximately one week following infection, major physiological changes begin to take place. Though the exact mechanisms are a subject of my ongoing research, I have found evidence to indicate that essentially, the viral DNA takes over the body's process of cellular differentiation, selectively altering certain parts of the human genome based on the final design of the organism. As the infected cells shift and divide according to their newly modified genetic instructions, the victim undergoes an agonizing reshaping of bones and soft tissues.

Worse, rather than being over in a single night, this agony is very long-lived. Unfortunately, because it places a great deal of strain on the victim's heart and body, many do not survive the transformation, as has often been the case in my own research. This, combined with the difficulty in locating infected individuals in the first place, has forced me to infer much about the stages of transformation, mainly from corpses of those who died in the process. In any case, it appears that the entire transformation is complete in six weeks. During that time, the unfortunate victim prefers isolation, and likely as a result of their torment, will lash out strongly at any who attempt to draw near.

Needless to say, the common notion of a werewolf who transforms at the full moon and then back again is biological fantasy, and the changes that the Lycanthropic Parvovirus enacts upon its hosts are completely irreversible. However, my personal mantra is that there is some truth to just about every myth, and as I present the information I have gleaned from my own research and that of my colleague, we will discuss just what biological adaptations are fiction, and which are rooted in unsettling reality.

Physical Changes

The earliest changes to occur in a victim's body are twofold - widespread hair growth and, in order to adapt to an increasingly nocturnal hunting pattern, heightened senses. Of course, thick fur is a hallmark of the lycanthropic appearance, and this is one aspect of the legends that is very real. It appears that the virus may reactivate a certain gene that plays a role in embryonic hair growth but is normally dormant in adults - SOX3.

Essentially, the result is generalized terminal hypertrichosis, a condition not without precedent in humans, though it is rare and not nearly as universal as what is triggered by LPV, and which causes the growth of terminal hair across parts of the body which are normally hairless, such as the nose, forehead, ears, back, etc. In fact, the only areas that remain hairless by the end of the lycan transformation are the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet.

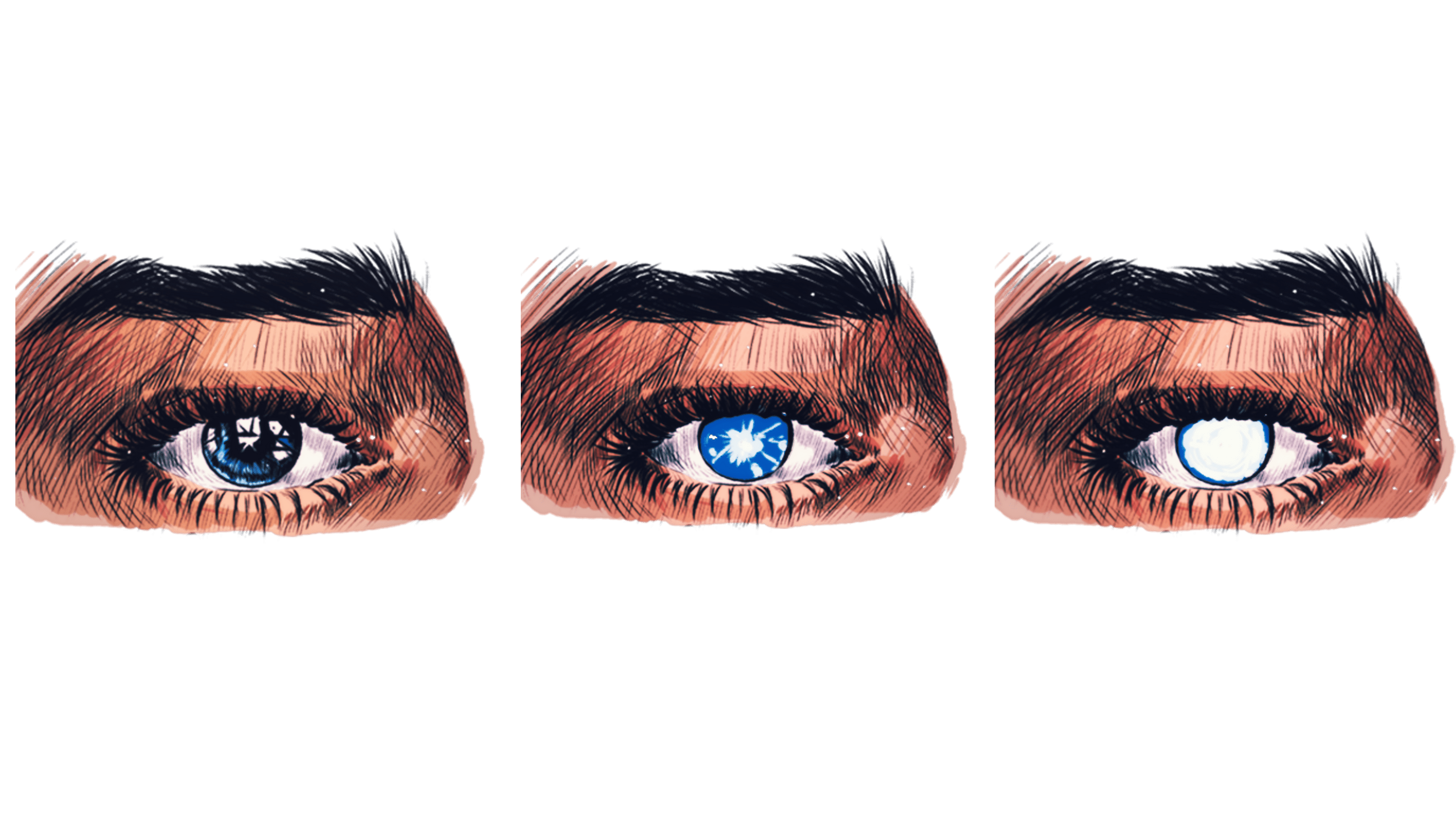

At the same time, an increase in melanin production turns the skin a very light or very dark gray, depending on the victim's ethnicity. Victims' eyes begin to appear bloodshot due to the increased blood flow, which supports the formation of tapetum lucidum tissue behind the eye, which serves to reflect light.

This greatly improves night vision and causes their characteristic eye shine. Toward the latter part of their transformation, loss of pigment in the iris brightens its hue to either a pale, icy blue or an intense yellow-amber coloration.

This is the primary sensory change that facilitates their newly nocturnal behavior, but changes in their brain also occur. Alterations to the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the hypothalamus work to entirely reverse the victim's circadian rhythm. Other senses are greatly improved as well. Auditory perception quadruples, while olfaction is nearly 100 times keener than that of an uninfected human. Autopsies reveal hypertrophic limbic neurons and a proliferation of receptor cells, which may explain these heightened senses.

Neurological Changes

One area of my research that still requires extensive testing is what occurs in the lycan brain. It appears that large portions of the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus are reduced in mature lycans, leading me to believe that this is at least partially to blame for their extreme aggression and apparent lack of reasoning abilities. Of course, some of this likely has to do with their often overwhelming need for food, but this is a point to which we'll return.

Skeletal and Muscular Changes

But while all of these changes begin relatively early in the transformation process, the next few weeks involve much greater and more fundamental modifications. Triggered by increased production of growth hormone from the pituitary gland and insulin-like growth factor from the liver, unprecedented bone and muscle growth occurs throughout the body and, as a side effect, causes the skin to swell and bruise.

In many major bones, such as those in the arms, legs, hands, and feet, highly enchondral cells in the epiphyseal plate, a zone normally dormant in adults, are reactivated. In these particular bones, cartilage cells called osteoclasts break down bone tissue by dissolving its mineralized matrix, a process known as bone resorption, while chondrocytes form new cartilage to replace the missing bone. Finally, fibroblasts strengthen the cartilage by reinforcing it with additional collagen.

Once this process is complete, cartilage can once again stack inside the open growth plates and spread across the outside of the skeleton to form new bone tissue via osteoblasts, which replace old cartilage as it degenerates.

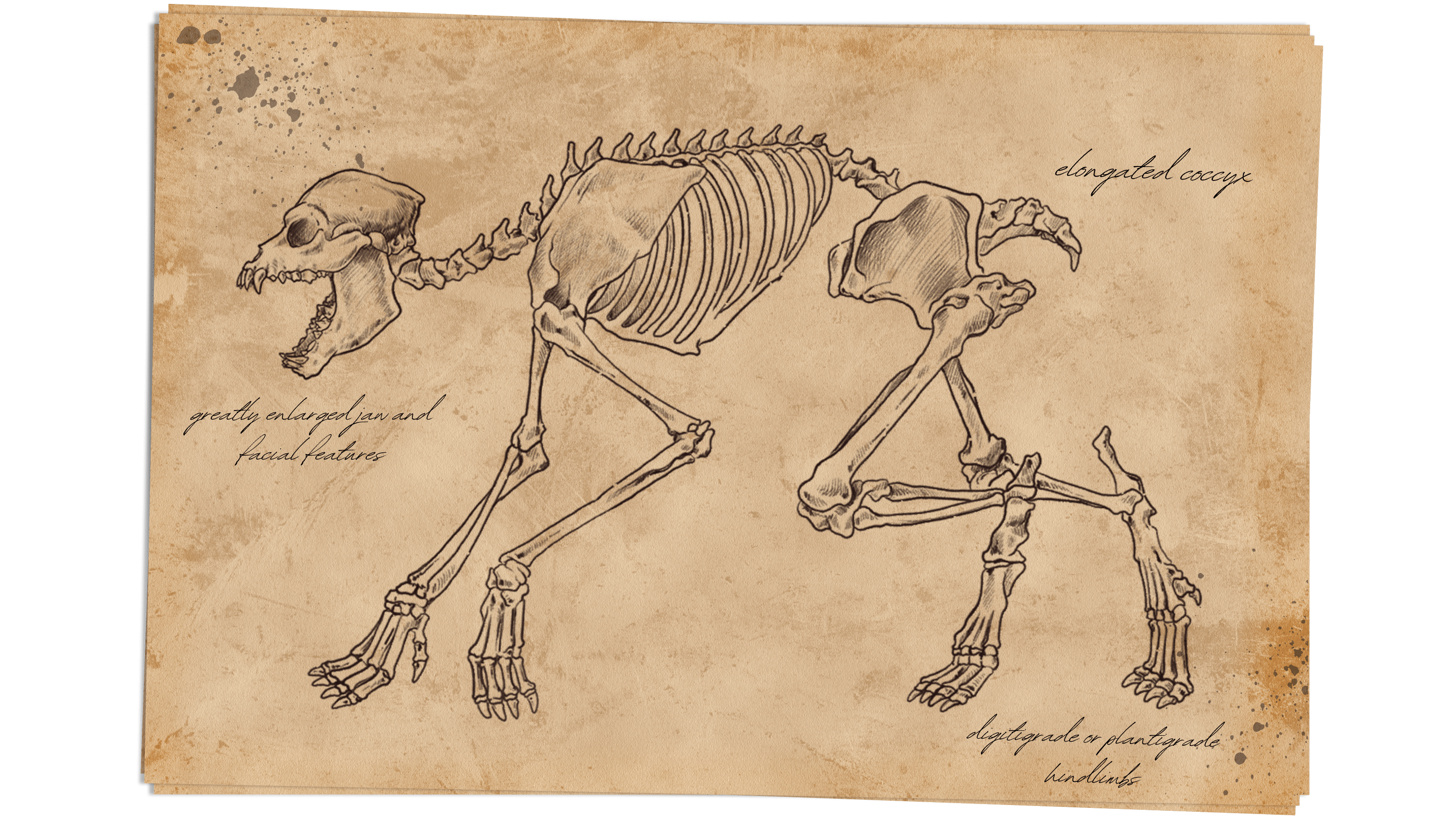

But bone that grows in length alone could quickly become brittle, especially when the force of the victim's added muscles acts upon it. To resolve this, most larger bones in the lycan's body also undergo appositional growth, which causes them to increase in diameter, thereby greatly increasing their density and strength. Interestingly, the coccyx or tailbone is also elongated, forming a rudimentary and largely non-functional tail of sorts.

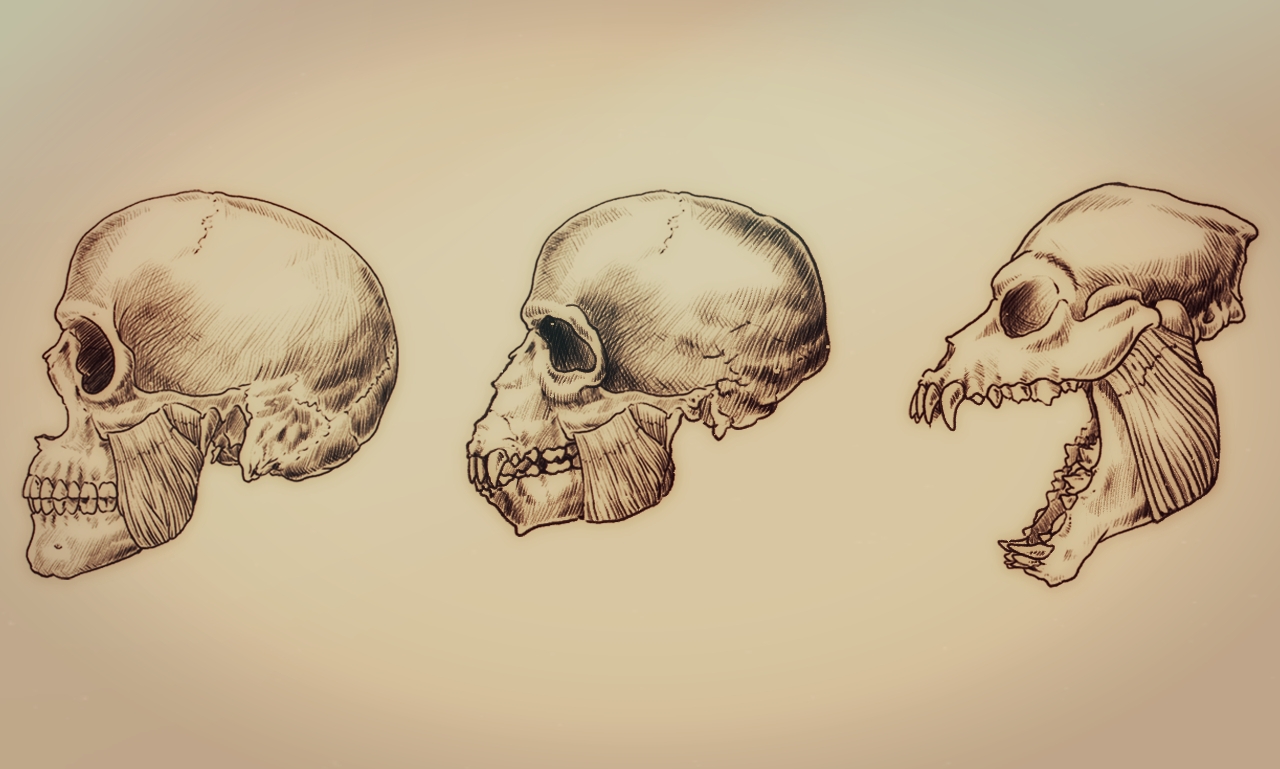

These processes are mostly finished by the end of the six-week period, though less pronounced growth may continue for years following the transformation. But perhaps the most drastic and obvious changes occur in the bones of the face and skull.

Facial Restructuring

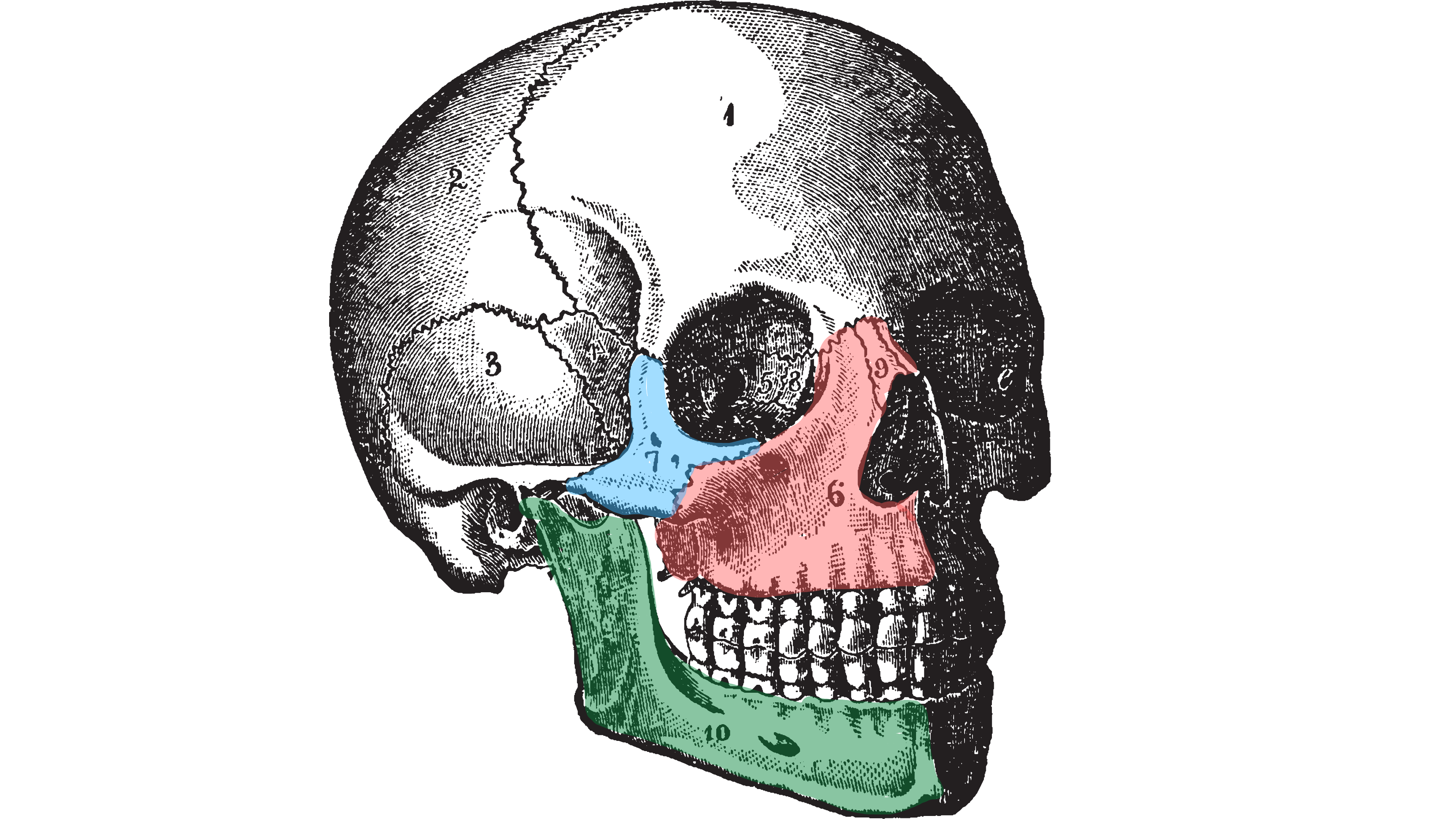

Beginning at approximately one week post-infection, the visceral cranium undergoes massive restructuring. The maxilla, mandible, and nasal bone, facilitated by additional ossification triggered by the same processes as the rest of the body, begin to drastically elongate.

Other affected bones are the zygomatic bone and arch, which add thickness to support the enlarged facial bones. Additionally, the anterior nasal aperture is shifted forward along with the surrounding bones, and new layers are added to the spongy matrix within the nasal cavity. As the nasal bone and maxilla push forward, the lateral, alar, and septal cartilage of the external nose are compressed, and the fibrofatty tissue that makes up the nostrils is redistributed slightly, severely flattening the nose, while the lower jaw shifts forward slightly and undergoes elongation via similar processes.

Observations of corpses who died in various stages of this transformation indicate that the facial bones and jaw don't always grow at the same rate, sometimes leaving the lycan with an underbite or overbite until the transformation is complete. Though not nearly as pronounced as many depictions in art and the media portray, by the end of the roughly six-week period, all of these changes do bestow upon the victim an almost mesocephalic snout, and one that is admittedly strikingly canine in appearance.

Accentuating this lupine visage is a tightening of the auricular muscles, which usually serve to move the ears slightly back and upward, positioning them higher on the head and aiding the lycan's enhanced hearing. Eventually, perhaps months after transformation, a gradual and unknown process also seems to collapse certain cartilage in the ear's helix, giving it a distinctly pointed shape.

Dental Changes

But of course, these aren't the only changes that occur in the head. Dentition is also substantially altered. Normal humans have a total of about 32 teeth: 4 canines, 8 incisors, 8 premolars, and 12 molars. Like wolves and bears, however, lycans have up to 42: 4 canines, 12 incisors, 16 premolars, and 10 molars. It also appears that a triggering of odontogenesis essentially causes a condition known as hyperdontia, which results in the growth of supplemental supernumerary teeth.

As of this recording, I have yet to determine exactly how this happens, but my research suggests that these teeth develop from additional tooth buds that arise directly from the dental lamina or perhaps split from the bud of the original tooth itself. In normal humans, hyperdontia would likely cause severe overcrowding, but because the lycan jaws also elongate, space is not an issue.

Additionally, the canine teeth are substantially enlarged, as specialized ameloblasts travel through the narrow pores of the dentin and crown, and once they reach the surface, deposit additional enamel onto its tip. This is very similar to what occurs in vampire dentition, and with similar fang-like results.

Finally, the chewing muscles of the jaw, namely the masseter, pterygoid, and temporal muscles, are greatly enlarged, which gives fully transformed lycans an immensely powerful bite force. I have yet to determine a controllable method to test just how powerful it is, but I will add these findings when they become available.

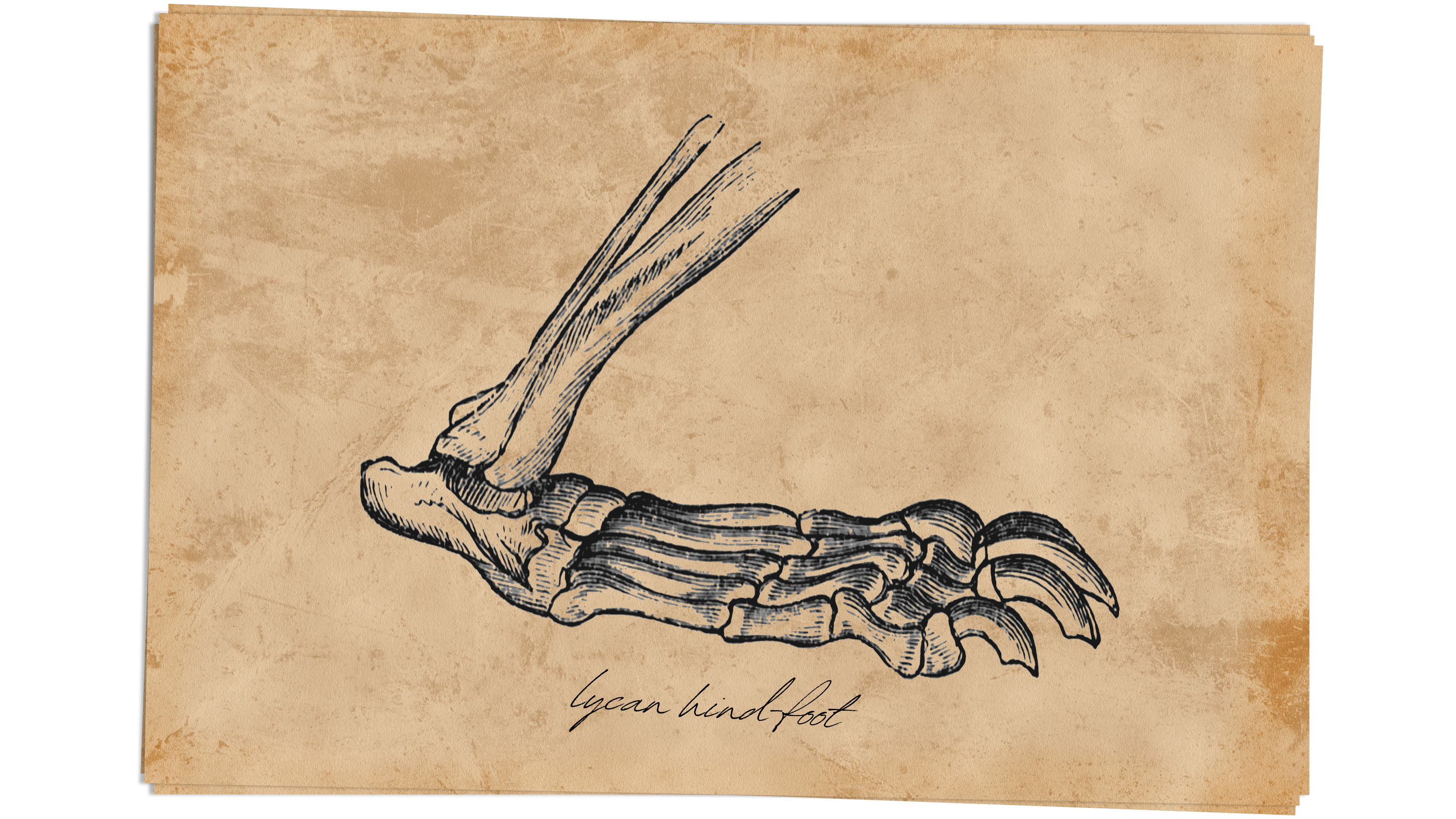

Hands and Feet

But we cannot move on from the subject of lycan bone structure without discussing their hands and feet. During the mid to late part of their transformation, the victims' nails on both fingers and toes begin to loosen. Eventually, they will fall out entirely, as the distal phalanges bones grow into hooked claws. These slowly erupt from the former nail beds, as hard keratin forms around the new quicks.

Though they are initially short and small, these claws can grow to over six inches in length. By the end of their transformation, the lycan hand is strikingly similar to the claw of a bear, and lycans' use of their thumb is similarly restricted, making it easier to move on all fours.

A fully transformed lycan's feet also exhibit similar claws. Thanks to the elongation and thickening of the forearms, feet, and spinal column, moving in a quadrupedal stance appears to be remarkably comfortable for a formerly fully bipedal creature. Though thanks to their newly-shaped feet, which are generally plantigrade during bipedal movement and digitigrade while on all fours, and their enlarged pelvic and shoulder girdles, moving between stances appears to be equally comfortable.

Internal Changes

But comfortable is not a word anyone would use to describe the transformation process itself. It is likely immensely painful, like severe and pervasive growing pains sustained for weeks. This pain is likely compounded by the numerous changes that occur in the internal organs.

Though the digestive and cardiovascular systems remain largely unchanged structurally speaking, most organs, including the heart, become greatly enlarged in order to cope with the lycan's increased body mass. In fact, the heart is so enlarged that fully transformed lycans experience a decreased resting heart rate of around 40 to 50 beats per minute, similar to that of a large bear.

As such, the physiological reliance on this organ makes them much more vulnerable to chest injuries, especially since their ability to clot blood, heal injuries, and fight infection is not superior to humans and other mammals. The common conception that silver is more effective than any other kind of bullet is pure fiction.

Older lycans also exhibit shorter digestive tracts, likely an adaptation to their diet, which leads directly to my next point. Although their increased muscle hypertrophy, the extreme alterations in skeletal composition, and their increased overall metabolism require infected individuals to consume copious amounts of food, and more specifically protein. Though they prefer isolation a majority of the time, lycans are not picky when it comes to food sources. Indeed, any living thing in close proximity to a lycan is truly in mortal danger, and they will likely fall victim to these beasts' insatiable appetite.

The Final Result

The net effect of these extreme alterations to the humanoid body plan is clear. Post-transformation, victims of LPV are reduced to an aggressive, animalistic state. Legs and arms are restructured to allow for effective locomotion in both bipedal and quadrupedal stances. The facial muscles and bones form a kind of snout, and medium-length hair covers their entire body. These stark and even radical changes are cemented until the poor creature dies, though I have no evidence to show that lycan lifespans are longer or shorter than the average human's.

Needless to say, it is clear where the persisting legends of werewolves come from. But one nagging question has likely already occurred to you as it did to me in the early phases of my research: Why would a virus induce a transformation that requires such a high biological cost?

My hypothesis is simple. The virus itself likely originated in canines in the distant past, and through a process known as horizontal gene transfer, it likely assimilated so much of its host's genome that it has little choice but to express similar characteristics in any host it infects.

It just so happens that primates are the only other mammals it's capable of infecting.

Generally speaking, based on the discovery of dozens of well-preserved fossils, records of which were provided by my deceased colleague, I believe that the first true lycans originated in the forest-heavy landmass of Eurasia, possibly after infecting and wiping out our Neanderthal cousins. As humanity progressed into the medieval era, we never lost the deep-seated fear of our lycan predators. As a result, legends of distant lands populated by dog-headed men persisted, as did the concept of the terrifying werewolf. Even today, these legends are ingrained in our culture.

Conclusion

Many have thought of lycanthropy as a fictional metaphor for the duality of man, a personification of the ongoing struggle between the enlightened person and our basest instincts. But while these discussions may have merit, the reality is that lycans, werewolves, are very real.

Some night, my dear reader, you may find yourself wandering through a lonely wood. You wouldn't see the attack coming, and if you miraculously survived it, you'd retain your wits long enough to see your skin grow fur, your limbs lengthen, and claws sprout from your fingertips. As the agony and madness overtake you, prompted only by a lowly virus, metaphors and philosophies will not cross your mind.

You'll be consumed by only one thought: hunger.

Comments