Iuxat

Writing System

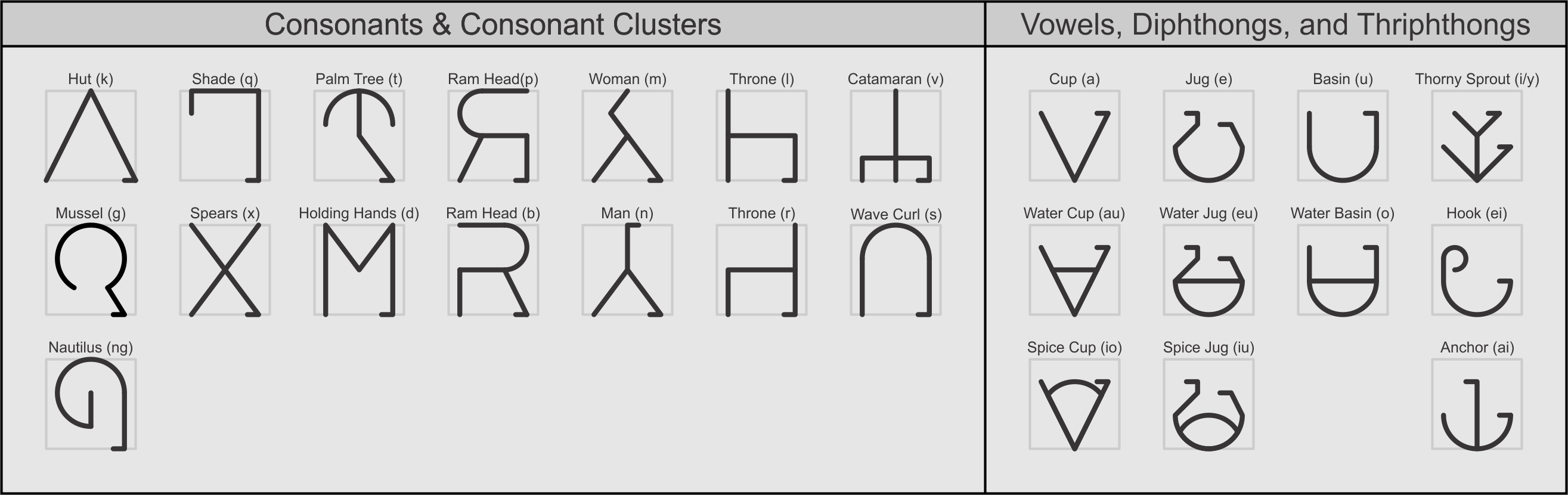

The alphabet of Iuxataba. Also known as the 'Eiqa Adiuxataba' - meaning 'The Spirit-Script's Substance' - or the 'Kaqata' for the first three sounds in the alphabetical order. The grey outlines demonstrates the relative size of the letters and the typical empty space (kerning) between them.Iuxataba, the written form of Iuxat, is an alphabet, though a few characters code for dipthongs, tripthongs, or consonant clusters. It is read left-to-right, then top-to-bottom. Word breaks are indicated by spaces. While sentence breaks are often indicated with a space, vertical bar, and another space in machine-generated text, written, artistic, and official writing often encloses sentences in rectangular boxes.

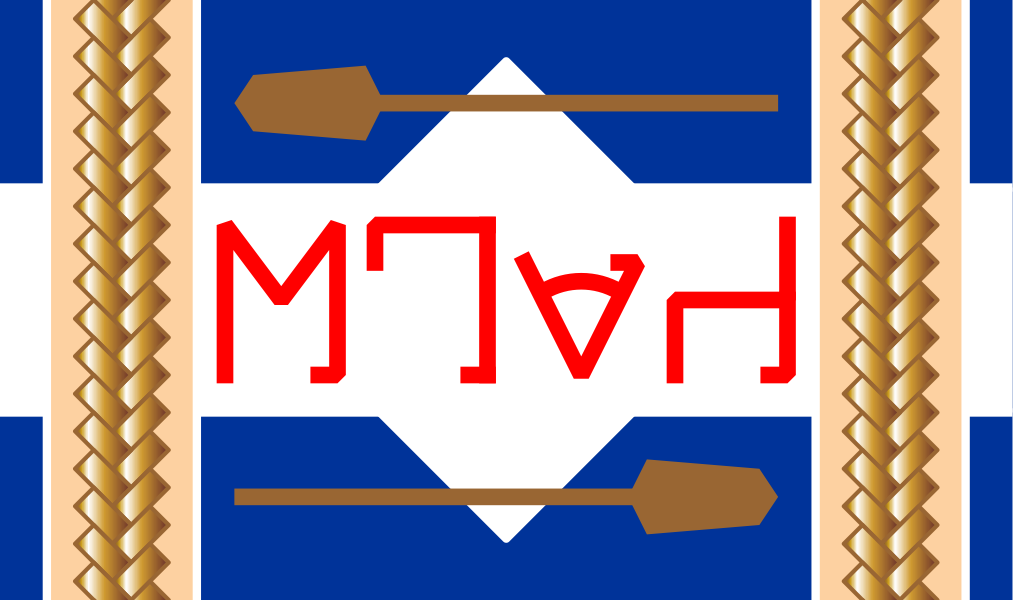

The ensign of the Rostran Archipelago Confederacy Marine Forces featuring an example of Iuxataba abbreviation at center. Note that only root words, not particles other than "ux," are included in the abbreviation "DQIoR" for "osanDexai adQamna aderetasIost adovRostra".

The original glyphs of Iuxataba script were ideograms for common sights in the Rostran home islands (i.e. spears) and took on phonic meaning based on the first sound in the words they represented. Occasionally, neologisms will enter the Iuxat lexicon entirely as a result of the imagery associated with Iuxataba script rather than any obious cognate. For example, the verb "nedaum," meaning "to marry," came about because, when the word "nedaum" is written in Iuxataba, the characters resemble elements of a traditional High Rostran wedding ceremony.

Iuxataba was traditionally incised into hardwood with chisels. Later versions of the alphabet are written with flat-nibbed squid ink pens on thin wood scrolls, introducing curves, serifs, and thickened strokes on the leftmost vertical lines. Modern Iuxataba script is written with clockwise strokes on consonants and counterclockwise on vowels.

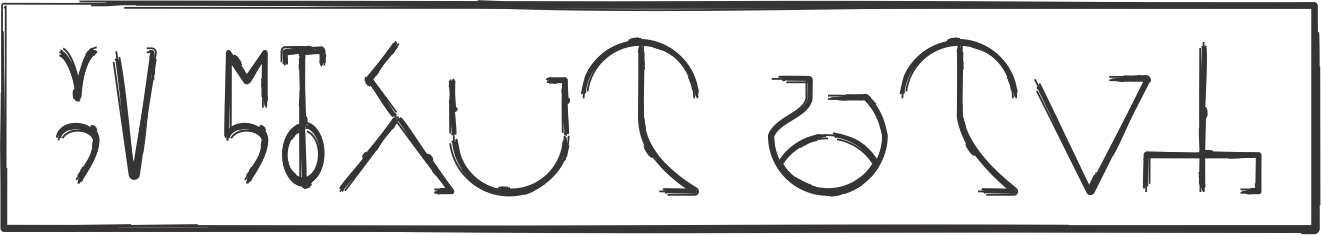

'Iuxataba' as written in Iuxataba.

Iuxataba script is generally written with the bottoms of all characters aligned with one another, though sometimes the tops will be aligned instead for stylistic effect. The difference in height between consonant and vowel characters helps the reader distinguish between the two.

Name mark of Eudoxia Chemical Group. Note the 'eu' letter in the center stylized to resemble a chemical vessel. Also note the vertical shifting of the vowel letters for stylistic effect.

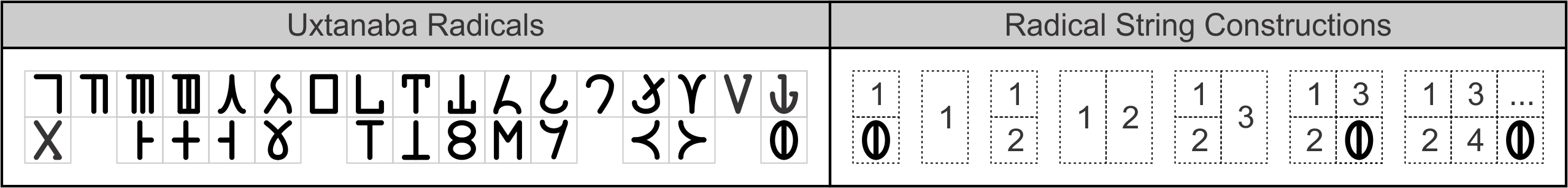

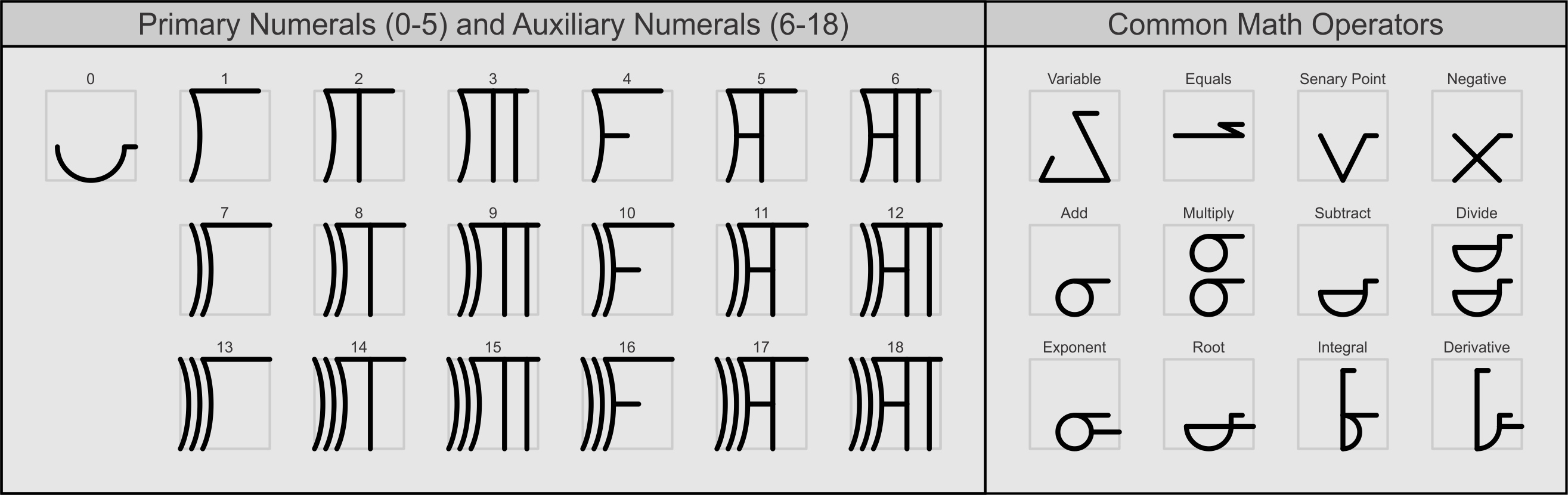

In handwriting (though not calligraphy), non-right angles like those found in the “t” and “e” glyphs are often rounded for expediency. The serifs may be altered, such as by angling them or turning them into arcs and curls, as a further means of stylization. Various cursive scripts have been proposed, but none have achieved universal adoption across the Iuxat-speaking world. When brevity or compactness of writing is required, a system of radicals, known collectively as "Uxtanaba" (a portmanteau of "small writing"), can be used to compress whole particles down to individual logographs. Uxtanaba symbols each take up half the vertical and horizontal space of a Kaqata letter. Uxtanaba are stacked up to two high per line and are read top-down, then left to right. Clusters of Uxtanaba glyphs are separated from one another by spaces between words as normal for Iuxataba script. A special space-filling glyph may be used to ensure that no glyph is left 'floating,' though some writers stretch the final glyph vertically instead to prevent this. Ligatures may be applied to unite Uxtanaba systems into single glyphs for purely aesthetic purposes. The adoption of Uxtanaba is by no means universal in the Iuxat language community and the radicals are more likely to come up in technical contexts where an advanced knowledge of the language is expected or, alternatively, in pieces of advertising where space is at a premium. Uxtanaba radicals. At top left: er-, eret-, eretas-, otas-, eun-, aum-, ul-, eus-, utab-, iot-, aqit-, osan-, ix-, eiq-, ov-, -a, -ia. At bottom left: ux-, ag-, non-, ran-, up-, ar-, ukar-, as-, ad-, on-, ol-, ul-, (gap filler). At right: several examples of valid constructions for strings of Uxtanaba radicals. How a Hierophant named Iutav, dedicated to the service of the faithful of Ixutabmut, might sign his name on temple documents using Uxtanaba radicals. Note that the grammar of Iuxat enforces a space between the "ovixa" (priest) and "adixutab-" (particles for possession and parts of a a spirit's name) clusters. Iuxataba glyphs can easily be distinguished by the locations of their serifs and, to a lesser extent, by their sizes. Consonants are denoted by full-sized glyphs with inward-facing serifs at their bottom right extent. Vowels and vowel combinations are denoted by inward-facing serifs at their top right extent. Numerals and mathematical operators (see below) do not encode phonemes as such, but can be distinguished by outward-facing serifs on their upper right extent. While numerals are full-sized glyphs, math operators are typically shorter and narrower. The numeral immediately preceding an operator indicates the number to be 'worked on' (i.e. the numerator of a fraction or lower bound of an integral), while the following number is the one doing the 'working upon' (i.e the divisor of a fraction or upper bound of an integral). When performing math, individual operations within a problem are enclosed in boxes to indicate that they are performed separately from one another, thus disambiguating the order of operations. A math operator missing an argument from one side accepts the whole boxed operation on that side as the argument; in this sense, operators serve a purpose akin to that of grammatical conjunctions. Spellings in Iuxataba are phonetic. Each phoneme, digraph, diphthong, and triphthong (see phonetics) has its own glyph in the Iuxataba orthography. Phonemes and phonemic clusters denoted with digraphs in the Iuxat romanization are always written with their associated glyphs wherever they might appear. The one exception to this rule is that digraphs coincidentally formed from the proximity of other words or the addition of prefixes to root words are instead spelled with two phonetic glyphs and are not phonologically 'fused' in this manner. For example, if one wanted to address their shy brother by the slang term "eungogong" ("mussel" with the masculine declension), the /n/ phoneme in the "eun" particle and the /g/ phoneme in the "gogong" root word would be spoken as separate sounds and denoted with separate glyphs rather than the single for the /ŋ/ phoneme normally romanized as "ng". The Kaqaba, arranged in alphabetical order and pronounced as each letter name, proceeds as follows: "ka, qa, ta, pa, ma, la, va, ga, exa, eda, ba, na, ra, sa, enga, an, en, un, in, aun, eum, om, ein, ion, iun, ain." When words in Iuxataba are alphabetized, they are generally sorted by the first letter in their roots. Strings of prefix particles - including those which are integral to the meaning of these words, such as "ux" and "ov" - are then used to sort the subsections of the list that share a root. The first six letters can also serve to denote the first six notes in the Rostran hexatonic scale. This musical scale forms a chromatic scale when combined with the notes shifted up one 'movex' ("ka, ka movex, qa, qa movex, etc" a 'semitone' shift in Iuxat notation is equivalent to a full tone shift in chromatic.

Phonology

Syllables in Iuxat generally take the form of (C1)(C2)V(C3)(C4). Particles always end with a consonant. The sounds /ŋ/ (ng) and /ks/ (x) generally cannot occur at the beginning of a word (C1), and /kw/ (q) cannot occur at the end of a word (C4). The sounds /ks/ and /kw/ also generally cannot appear before another consonant within the same syllable (i.e. as C1 or C3 in the presence of C2 or C4 respectively).

When spoken, emphasis is usually applied to the first syllable in the first particle affixed to a root and on the first syllable in the root word itself. For example, the spirit Ixaumosana's, the emphasis is put on the 'Ix' and 'os' syllables. This helps speakers differentiate between a string of particles and the root to which they are affixed. Verbs often have the emphasis moved to the last syllable in the root word to provide additional clarity when the root can serve multiple grammatical roles within the same sentence. For example, the sentence "aqitkorve nonkorve" translates to "the bird is currently flying." In this sentence, because the root "korve" can be a noun ("bird") or a verb ("to fly"), emphasis would be place on "aq" in the animal particle, "ko" in the noun, "no" in the tense particle, and "ve" in the verb to help distinguish how the root is being employed at a given time.

Gemination does not occur within root words, but it rarely occurs when a particle is applied to such a word; in Iuxat's orthography, this is denoted by the repetition of the sound in question. As a special case, fishermen using the "Noniuxat Assoxa" (lit. "speaking like fish") professional dialect can apply gemination to the vowels of direction words and associated particles to imply heading and distance.

Morphology

Iuxat is agglutinative and features numerous particles which may be applied as prefixes to inflect words. Particles may be omitted if the information they encode is redundant (i.e. Vex is the speaker's brother and the speaker knows Vex is a man, so (second person familiar) can be used to address him without the (masc.) particle). Particles often take the form of a vowel-consonant pair.

For nouns, the following particles exist and generally occur in the order presented:

- Transitive Context: ol- (direct object/accusative case), il- (indirect object/usually dative case). "Ol-" is the modern version of the archaic "ir-" direct object marker that sometimes appears as an influence in the "i(r)-ot" construction (see Uncommon Constructions below). The direct object marker is an optional tool for clarity and is often elided in cases where the sentence is simple (i.e. "ato, ami aika" for "I love you") or the context needs no additional clarification to be legible to the speaker (i.e "ato ilkorkra, ato stoda." for "sculpt yourself from stone"). The indirect object marker, however, is almost always necessary to differentiate these words from adjectives applying to the direct object and to indicate the target of transitive verbs.

- Negatory: ux- (negates following particle or word). For example, "uxeriot," being "(negatory)(single)(discrete object)," means "Not a single thing." The ux- particle may be located later in the order if the element it negates is important to the meaning of the word. For example, the phrase "eretasuxula," being comprised of (many)(negatory)(inanimate things), would mean "many things which are not inanimate," as opposed to "uxeretasula," comprised of (negatory)(many)(inanimate things), which would mean "a few (not many) inanimate things." The ux- particle is also somewhat polysemous in the sense that it can modify more than just nouns to create antonyms - words with an opposing sense to the root (i.e. "uxpolam," meaning "to dirty or soil," uses the ux- to modify the verb "polam," meaning "to clean"). Iuxat lacks a hard rule against double negatives, with multiple instances of "ux-" being possible within a single construction, though these may sometimes be phrased differently for clarity.

- Gender: eun- (masculine), aum- (feminine), ul- (inanimate/non-humanoid). If a living non-humanoid creature has a known gender, the masculine or feminine gender is applied as appropriate after the particle for non-humanoids (uleun- for male and ulaum- for female).

- Plurality: er- (single), eret- (plural in the sense of 2-5 items), eretas (many in the sense of 6 or more items), otas- (all)

- Type: ov- (person), utab- (plant), aqit- (animal), iot- (discrete object), eiq- (substance), osan- (water/liquid), eus- (place), ix- (spirit). The (spirit) particle, added before any other particles, implies that the thing in question exists only as a spiritual entity; whether such an entity is mythological or simply deceased is inferred through context.

Verb Tenses

Iuxat features past, present, and future tenses - in both the perfect (aorist) and imperfect forms - as well as an infinitive tense. For verbs, up to two inflection particles are applied as prefixes to indicate tense. The first particle indicates when the action began, and the second indicates when the action ends. A single particle may indicate an instantaneous action or, conversely, that the action begins and ends in the same tense. Statements which are implied to end before they begin (i.e. "ranagkorve") don't make logical sense but are nevertheless valid constructions, implying irony, nostalgia, or an implication of somehow communing with something which has been lost to time (i.e. funeral rites). Sometimes, affixing a tense particle to a noun turns the noun into a verb relating to what the noun does; for example, applying a tense particle to the word "soxa" changes the meaning of the word from the noun "fish" to the verb "to swim." When used alongside other verbs (i.e. "going to do something"), infinitives are generally placed immediately after that verb in the manner of an adverb ("olosang ileusduqu adami, ami agvolu upsoxa" transliterates to "to the river from my house, I went to swim."). In the rare case where both the verb taking place and the infinitive used to elucidate the action taking place are the same, the infinitive particle may be used in place of the second particle. (i.e. "agupvolu" for a statement like "I was going to go to the store," or "nonupakau" for a statement like "The color of the car is to be determined"). Vernacular speakers of Iuxat sometimes use the infinitive form of a verb as its gerund (i.e."to run" realized as a noun meaning "running" as in an activity) The tense particles for verbs are:- Past: Ag-

- Present: Non-

- Future: Ran-

- Infinitive: Up-

Pronouns

Pronouns are constructed by adding noun particles (if necessary) to the following roots:- First Person: Ami (I/me "we" is constructed by affixing the (plural) particle to the first person pronoun

- Second Person: Ato (you familiar), Atodai (you not familiar/formal)

- Third Person: Alu (he/she/it familiar), Alugai (he/she/it not familiar/formal)

Syntax

Iuxat uses object-subject-verb (OSV) grammar (i.e. "The store, I visited"). In general, everything before the subject phrase is separated from the rest of the sentence body by a pause of around one or two syllables in length, usually transliterated as a comma, for additional sentence clarity. Adjectives and adverbs follow the parts of speech they relate to. For the sake of expedience, most speakers drop any parts of speech not required for context. For example, one might construct a simple command by dropping everything but the verb from a sentence (i.e. "Rut!," literally "Carry!," could be construed as meaning "I need you to carry this right now!"). Various particles can be indirectly employed to mark where polysemous words are being used as different parts of speech within the same sentence.

Iagot/irnonot/iranot: in the past/future/present where (x) happens, (y) also happens

Irupot: in order to (x) or make (x) happen, (y)

Ireusot: in the place where (x) happens, (y) happens.

Irovot/iaqitot/irutabot: as a person/plant/animal which does (x), (y)

Ireunot/iraumot: as a man/woman who does (x), (y)

Irixot: in the spirit of (x), (y)

Iriotot/ireiqot/irulot: for an object/substance/being where (x) is the case, (y)

Iarot/Irukarot: in the maximal/minimal case where (x) happens, (y) happens.

Iruxot: in the case where (x) does not occur, (y) happens.

The "i(r)-ot" root also has relational variants that don't require the inclusion of a case or tense particle. The words "inosot" and "imusot" function as "In this case" and "in that case" respectively. "Inosot" is used to refer to current events, while "imusot" accepts the previous sentence in the conversation in the place of (clause x) as outlined above. The word "irgot" is an all-purpose relational meaning "in the case of/that (x), (y)". A relational can also accept the negatory “ux-” particle to indicate a relation between the clauses where (clause x) does not come to pass. For example, the construction ‘uxirovot (x), (y)’ might be translated as ‘as a person who isn’t/doesn’t (x), (y).’ This serves to further simplify the use of the negatory particle within the clause by preventing stacking; the elements of the clause affected need not agree with the negatory case.

Possession

Applying an "ad-" prefix to a noun implies that it possesses whatever noun come before it (i.e. "Checkov's friend's gun" becomes "(gun) ad-(friend) adQekov"). This word order, along with possessive prefix, can sometimes be ignored when words are created through agglutinization; for example, the word "Tangada," meaning "leaf," is a direct combination of the words for "tree" ("tanga") and "hand" ("da").Semblance

A common saying about Iuxat is that simile and metaphor are the soul of the language. Applying an "as-" prefix to a word puts it in the semblative case, and it now functions as an adjective or adverb (see above). A noun with this prefix means that the object or subject which it follows has the properties of the noun in question. For example, the construction "ato assoxa" implies that the speaker thinks that you are a "fish-like person," perhaps implying that you are an excellent swimmer. A semblative noun following a verb implies that the action is taken in the manner normally ascribed to that noun (i.e. "You throw like a girl!" becomes "(fem.)(second person not familiar) (present)(throw) as(fem.)(person) (young)!"). The semblative case particle can also be used to denote when an otherwise polysemous word is being used as an adjective or adverb - as opposed to when a noun case or verb tense particle is employed. For example, the word "ilem" can denote the noun phrase "spiritual discipline" in the form of "ixilem," the adjective "disciplined" or adverb "with self-restraint" in the form of "asilem," or the verb phrase "will exercise discipline" in the form of "ranilem." Whereas the "as-" prefix can put an individual word in the semblative case, the conjunction word "iasot" can put the entire following clause into the semblative case. This allows a broader palette for the construction of analogies, similes, and metaphors. For example, the analogy "A bird flies like a fish swims" could be constructed as "erkorve nonkorve iasot ersoxa nonsoxa." Similarly, the phrase "just as the bird flies, the fish swims" could be constructed "iasot korve nonkorve, soxa nonsoxa."Superlatives

Adding an "ar-" prefix particle to an adjective or adverb puts it in the positive superlative (most, greatest, largest, etc.) case. The prefix "ukar-" instead puts the adjective or adverb in the negative superlative (least, smallest, etc.) case. The use of "uk-" in lieu of "ux-" for the negative superlative is done to help differentiate this particle from an "ux-" used to negate the root and, therefore, present a different meaning. For example, the word "ukaruxidio," meaning "least light-colored," would confusingly contain the "ux-" particle more than once under the normal rules for Iuxat word construction. As with the semblative case, the superlative prefixes can help disambiguate the marked word's status as an adjective or adverb within the sentence structure.Number of Items & Times

Number is indicated as an adjective or adverb placed after all other modifiers except the time modifier and implies a specific number of individuals (for nouns) or specific number of times something happens (for verbs). Number may be used in addition to plurality particles for better specificity or emphasis. Using the "ad-" prefix for a number placed after a noun or verb, in the manner of a location (see below), instead makes the number ordinal. For example, the phrase "eretkorve vexet" means that there are four birds, but "erkorve advexet" means that the speaker is referring to the fourth of several birds. Because numbers and directions share root words, it may be required to use "adeus-" rather than a simple "ad-" to indicate that the directional meaning is intended in the presence of this sort of ordinal meaning. For example, the object to the left of the third item in a series might be described as being "iota advex adeusvex." To create a time modifier, the particle "on-" is applied as a prefix to the word for a unit of time, and an ordinal number (see above) is applied after the word to indicate how many units of time have elapsed since, are elapsing, or will elapse; whether this time relates to how long ago something happened or how long it will take to happen is inferred from the tense particles of the preceding verb. For example, "We three men went to the dock twice four days ago!" becomes "Dock (masc.)(plural)(first person) (three) (past)(go to) (two) on(day) ad(four)!" The "on-" particle can also be applied to a verb or, less commonly, an adjective to condition an action on when that verb occurs (as in the construction for "When I arrived at the beach, I saw her") or when that adjective becomes true (as in the construction for when a driver says they are going to "go on green" at a traffic light). Such time statements are usually treated as adverbs in terms of placement within the sentence structure, but may also be placed at the head of a clause or between clauses in support of conjunctions (as in the construction "But when the walls fell, no one came to meet us"). For example, the phrase "I was sad when the rabbit died" could be translated "ami ovo agakau onmut adlepi" (I was sad upon the death of the rabbit) or "onagmut adlepi, ami ovo" (upon the death of the rabbit, I was sad). In another example, the phrase "I wept, but when I ate starfruit I felt much better" could be translated "Ami agblubu, abo onagioruk adikta, ami ovo nonuxuname" ("I cried, but on eating of star fruit, I no longer feel sad"). The conjunction word "ironot" can put the entire following clause into the temporal case in the same way that the temporal case particle "on-" can turn a word into a time-based conditional. For example, the phrase "the karpik swam away when I shouted" might be translated "karpik agsoxa adusev ironot ami agana," while "when I shouted, the karpik swam away" might be translated "ironot ami agana, karpik agsoxa adusev." The Rostran linguistic conception of time divides the day into eighteen equal portions based on the division of the day hours and night hours into three spans of time each:- "Onrisab" - Morning, extending from sunrise until roughly two hours before midday.

- "Onris" - Midday, extending roughly two hours before and after midday.

- "Onrisik" - Evening, from roughly two hours after midday to dusk.

- "Onluxab" - Waning Twilight, from dusk to roughly two hours before midnight.

- "Onlux" - Midnight, extending roughly two hours before and after midnight.

- "Onluxik" - Waxing Twilight, from roughly two hours after midnight to dawn.

Locations

Nouns are considered to 'own' locations around them, and this construction is also used to indicate how a verb relates to a subject; in other words, both possession and location are denoted by the locative case prefix "ad-." For example, "The inside of the store" would be constructed as "inside ad-store" whereas "We went into the store" would be constructed as "inside ad-store (plural)(first person) (past)(to go to)." The standard Iuxat dialect lacks 'to' and 'from' adpositions, instead, for example, treating "to go (to)" and "to come (from)" as different verbs. Many other transitive verbs also carry implied adpositions, such as "to receive (from)," that apply to the object of the verb, as marked with "il-", unless additional information is included in the statement (i.e. "with" in the construction for "I received this news with open arms" superceding the implied "from" or clarifying it after the fact). If additional information is required about from where an object originates, the sentence is constructed to imply that the noun 'belongs' to a location. For example, "It came from the beach" might be constructed "(object)(3rd person) (poss.)beach to come (from)." The conjunction word "iadot" can put the entire following clause in the locative case. For example, the phrase "Where the sunlight touches, this is our territory" could be translated as "iadot uxidio advatio nonitva, qesovil ileretami nos akau," while "we played were the water had departed from the shore" could be translated "eretami agomi iadot spet osana agitnad."Interogatives

Terminating a sentence with a lone "e?" sound turns the sentence into an interogatory statement (i.e. "You will go to Eurymaxim with me." becomes "Will you go to Eurymaxim with me?"). The word "emid?" is an all-purpose question word that implies that the part of the sentence it precedes to is the part the person is inquiring about. For example, the question "Who was this/that man?" might be constructed as "emid (masc.)(third person formal) (past)to be?" Using emi- as a particle in lieu of tense particles for a verb questions when the verb takes place. For example, "When did you (my brother) swim home?" might be constructed as "home (masc.)(second person familiar) emi(swim)?"Transitive Verbs

Iuxat is a nominative/accusative language. If a verb is a transitive verb - that is, it takes multiple arguments - then the appropriate preposition is assumed to be implied by the verb. For example, verbs for "to come from" and "to come to" would be separate verbs because the prepositions "to" and "from" are considered integral to the verbs. In the case of sentences like "I took the dog to the vet", the verb "to take (to)" accepts "dog" and "to the vet" as direct and indirect objects respectively. The indirect object (in the forgoing example, the vet) is given the multi-purpose "il-" prefix and is placed immediately after the object and any associated adjectives ("Pararo iloveirin, eretami agrolata."). As another example, the overly specific sentence "Yesterday, my wife and I hurriedly delivered our daughter to school" could be constructed "Our daughter to school, my wife and I delivered hurriedly yesterday," or "Auminiu aderetami ileusiloi, aumiun adami itiu ami aguxrolau onris er isoda," though, as Iuxat is already quite verbose, the speaker would likely elide the details and simply state "Ova uxtan ileusiloi, eretami agrut isoda" ("We quickly carried the little one to school") in the interest of brevity. The word "irilot" can cause the entire following clause to take the place of an indirect object, such as when discussing the method by which a verb came to pass. For example, the sentence "I transgressed against the natural law by stealing the spirit of the stone" could be translated as "anera irilot upkedan ixa adkorkra, ami saptat."Subordinate Clauses

Roughly translating to "that," the word "mot" in Iuxat is a conjunction that introduces the subordinate clause that follows it. The usage of "mot" typically follows the structure like (clause 1) mot (clause 2) mot (clause 3) and so forth, allowing for grammatical recursion as such. For example, the phrase "I was glad that the woman saw that the documents were prepared properly" could be constructed '(1st per.)(happy) mot (3rd per.)(person) (past)(to see) mot (documents) (past)(to prepare) (correct).' If there are only two clauses, then the order of clauses is not strictly enforced so long as the one following the word "mot" is the subordinate clause. For example, the phrase "I was upset that the table was not set" could be constructed as (1st per.) (upset) mot (table) (past)(neg.)(to set.), but it could also be constructed more poetically as 'mot (table) (past)(present)(neg.)(to set), (1st per.) (upset),' translating as "that the table was not already set was upsetting for me."Uncommon Constructions

Much in the same way that conjunctions like “iasot,” “iadot,” “irilot,” and “ironot” serve to associate clauses together (see above), the “i(r)-ot” root can accept almost any other case or tense particle as an infix to associate clauses with one another on the basis of what those tenses or cases represent. These ‘relationals’ are an uncommon extension of the idea behind the semblative case, but don’t strictly follow the conventions thereof when it comes to meaning. They are less common because less complex constructions will suffice in most day-to-day situations. Such relationals generally take the form of i(r)-ot (clause x), (clause y), but are less often used as (clause y) i(r)-ot (clause x). These relationals include:Vocabulary

While Iuxat sometimes makes use of loan words (called Iuxatizations), most words in Iuxat are created by creating portmanteaus from existing terms or phrases. For example, "Ixaba" - the name of the religious text central to Rostran Esotericism, is a fusion of the words "ix" (faith/spirit) and "aba" (written/script "Ix aba" literally means "written faith" or, "spirit-script" Similarly, the Rostran term for airships is a fusion of the nouns for "ship" and "sky," while the term for a computer derives from the phrase "it (inanimate) dreams." Many words in Iuxat exhibit polysemy, taking different grammatical roles depending on position in the sentence and the choice of particles to attach.

Math

Iuxat uses a senary (base 6) positional numeral system that incorporates a zero digit ('uxer,' or 'not one'). This derives both from the fact that six is one more than the number of digits most people have on one hand and because, as the Rostrans are frequent navigators on the oceans of Rostral D,, it is useful to be able to associate the numbers one through six with the individual faces of a cube layer (see Directions below). Indeed, the Rostran method of numbering cube faces is the original influence for the naming conventions of the Navigator's Guild. The zero digit in Iuxataba (see Writing System) is an upward-curved line with an accent on the right side, signifying an open hand. Numbers 1-3 feature a number of vertical tallies joined by an upper bar, the first tally always being curved to indicate directionality. As with the associated number words, numbers 4-6 are the same as numbers 1-3 respectively, with the addition of a 'plus three' operator - in the glyphs, a horizontal bar extending from the center of the first tally. Though not often used in hand calculations, numbers 7-18 can be constructed by reduplicating the first curved tally as 'plus six' and 'plus twelve' operators. Numbers are spoken word-for-word from the highest radix to the lowest, with all but the last (unit) digit spoken with an -i suffix. For rational numbers, radixes below the unit digit are expressed in a similar sequence, but with an -o suffix. The Iuxat numbering system also features a binary sub-base, with each alternating number featuring sounds similar to the one that came before: 'er' for one, 'ret' for two; 'vex' for three, 'vexet' for four; 'tas' for five, and 'taset' for six. Iuxat has a separate name for six, even though it would not appear in a radix on its own, because the Proto-Iuxat language from which it evolved featured a bijective number system. An 'uxo' particle placed before a number 'negates' the entire number, allowing for negative numbers to be expressed; indeed, subtraction is usually performed by adding negative numbers.Directions

Rostrans were well-acquainted with the number of faces in their home cube by the time they began to formalize their numeral system. Because of the association with the various faces of their home cube, each number in Iuxat is associated with a cardinal direction (0/no direction/stationary point, 1/north/forward, 2/south/backward, 3/west/left, 4/east/right, 5/down/radial out, 6/up/radial in). Inflecting a number with the (place) particle turns a number into its associated directional term relative to the cube. In modern times, this is set relative to a monumental compass rose in Exivaun; it was established as relative to the front door of the elders' conclave house by tradition before the time of the monument's construction. Adding the (place) particle to a number and then following this with ad-(pronoun/noun) construction indicates direction relative to where the indicated person or object is facing instead. Many Rostrans have such a keen sense of direction that they eschew this construction entirely, relying only on geological direction instead; this requires constant awareness of one's orientation relative to the cube. As their knowledge of the Manifold expands, many Rostrans are experimenting with a duodecimal (base 12) system in recognition of the additional faces found on a cube layer's adjacent layer (in other words, beyond a given cube's inflection layer).Phonetics

The phonemic inventory of Iuxat (with romanization in parentheses) are as follows:

- Consonants: /m/, /n/, /ŋ/ (ng), /p/, /t/, /k/, /b/, /d/, /g/, /v/, /s~z/* (s), /l/, /ɹ/ (r)

- Consonant Clusters: /kw/ (q), /ks/ (x)

- Vowels: /a/, /i~ɪ/ (i/y)*, /e/, /o/, /u~ʊ/ (u)*

- Diphthongs: /ai/, /eu/, /ei/, /au/

- Triphthongs: /aio/ (io), /aiu/ (iu)

Sign Language

The sign language equivalent of Iuxat is called Iuxatda ("hand language"). Iuxat speakers are more likely, overall, to also be fluent in Iuxatda than members of other language communities in the Manifold are to be proficient in their own associated sign languages. This linguistic proficiency is a cultural inheritance associated with the need to communicate clearly over long distances where voices might otherwise not carry well, such as over rough seas, or where the sounds of speech might bring danger to the speaker, such as in covert missions carried out by the Rostran Archipelago Confederacy Marine Forces. Iuxatda features the same grammatical structure as spoken Iuxat. Each phoneme and grammatical particle is represented by a gesture that can be performed using only the fingers on one hand, while whole root words generally (but not always) require more broad movements of the hand and arm. Two particles can be signed simultaneously, the signer's right hand gesture being interpreted first to match the Iuxataba reading order from the perspective of the observer. In this way, up to the final two particle gestures in a constructed noun phrase can be displayed even as the gesture for the noun itself is being displayed, greatly expediting the construction of sentences. Iuxatda also features more pre-constructed noun phrases than the spoken language - especially with regards to concepts relating to personal and spatial relations - and some of these gestures have become second-nature to insert into conversations even among Rostrans with unimpaired hearing.Notable Dialects

The form of Iuxat represented here constitutes the most commonly understood foundations of the language, but different regions of the The Rostran Arc play host to different dialects of the language which may bear understanding for Manifold travelers. Scientists, academics, and those working in technical fields often adopt the Eudoxian High Rostran dialect because of its extended vocabulary with regards to chemical processes and mechanisms. The Eudoxian dialect features additional noun declensions for gasses or vapors (osak-) and solids (okar-), as well as ingressive (temil-) and egressive (tetol-) case markers for nouns to which transitive verbs apply. These features allow speakers greater specificity with minimal additional effort required in terms of learning the language, but come at the expense of confusion when speaking with other speakers who use the less specific form of Iuxat's transitive verbs. There are indications that the Eudoxian dialect is moving towards vowel length distinctions as a means of further delineating magnitude or duration and (perhaps eventually) as a structural marker to enable free word order, but whether efforts towards the institutional formalization of this dialect will stymie these developments or cement them in place as official features of the Iuxat language in its 'teaching' form remains to be seen. Still Atoll and certain isolated communities in the Red Velvet Association have much more rigid social hierarchies than those found in the core Confederacy. Organizations which regularly deal with these communities - including the Avarix Corps - use the Still Atoll Scour dialect. This dialect features a number of phonemic shifts which make the language sound more ejective, unvoiced, and forceful overall. For example, /v/ becomes /f/, /b/ and /ɹ/ become trilled as /ʙ/ and /r/ respectively, /p/ becomes /ph/ and /k/ becomes /kh/ or /x/; the voiced /b/, /d/, and /g/ may be converted to their unvoiced counterparts for additional emphasis. Scour also features obligatory gender markings, expands gender to include a possessive marker for subordinates or slaves ("aummad-" and "eunmad-" respectively) and expands pronouns to include hyper formal forms for masters or high-ranking officials ("amigaira," "atogaira," and "alugaira" respectively). As a result of its dire associations, speaking in the Scour dialect elicits distaste and suspicion in most other parts of the Rostran world but is also sometimes used as an ironic 'flex' among affluent non-native speakers. Indeed, among Rostran members of the Burning Hearts Social Club, most uses of Scour caste terms are considered 'fighting words' regardless of their valence. The ‘Port’ dialect is a form of Iuxat in which the sounds are softened and the variety of noun cases pared back as a result of regular exposure to Vozendi speakers. Primarily spoken by port workers, whether along the seaboard or at transit hubs like skystations, Port is associated with New Voxelian expatriate culture and, by extension, the Voxelian stereotype of thinly-veiled pansexuality. In the most common form of the Port dialect, the /d/ sound is realized as /ð/, non-terminal /s/ sounds are realized as /ʃ/, terminal /s/ sounds are realized as /z/, and /v/ is realized as /ʋ/. Moreover, dipthongs and thripthongs with romanizations that contain 'i' have that /i/ sound replaced with a /j/ sound (/jo/, /ju/, /ej/, and /aj/ respectively). Particles for number are elided, being replaced with “ul-” for plurality and “iot-” for singularity when referring to inanimate objects, and the particles for male and female gender are fully elided. Most noticeably, many Port dialect speakers have begun to adopt the Vozendi word order (SOV) as an optional syntax when speaking to or about people or places not considered part of the speaker’s community. This order-switching quality introduces yet another linguistic measure of distance to the dialect, with the new orders of remoteness being: here with me (OSV, intimate to close), there with you (OSV, close to within a few strides’ distance), there with them (OSV, within sight to within a few hours’ travel), here with me (OVS, from a different face in the same cube), there with you (SOV, from another cube in the same tesseract), there with them (SOV, from a different tesseract or further, including the world of forms and abstract concepts). This unique syntactical feature may have inspired the creators of Wadoona, the fictional language that forms the basis of a Voxelian alternative reality game and artistic movement, who would have had some familiarity with the Port dialect as a result of the on-the-ground research that went into that project.Translation Examples

Babel Text

1. And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech.

2. And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there.

3. And they said one to another, Go to, let us make brick, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick for stone, and slime had they for morter.

4. And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.

1. A otaseusa aderiungat a aderiuxat agakau.

2. A upakau eusona agvolur, ionot iladvexet otasov aglanum, eusuxmeubo adiost, adSinar otasov agvioda; a agkavon adeusalo.

3. A alu iuxat alu, “Volu, updevet a upmioxa kuku koda otasami ungel.” A korkra adkoda alu akauda, a uxlip adogmau alu akauda.

4. A alu iuxat alu, “Volu, updevet ereuskavon tan a erqelek astanga, otasami ungel, ixosako qelek ranuxtesai; uxirupot otasami uxiuvit adpemu adotasia, updevet erlogux otasami ungel.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Otasova mabeul advosta a asotasia adnoben a adnoali. Otasova ilendo a nmasu, ixa agranmoltei, a irixot akevia, ilova ova simat vilad.

Hymn of the Rostran Archipelago

O, eusa!

O, eusixa ami aika!

O, ami ranedea upmenus adsped glos adato,

Asia ami ranagmenus onris agaga.

O, eusa!

O, eusmadi asaumesui!

O, otasiost adarsunmara ad adami,

Otasigevt a duqu adami ilato ami rolau.

O, eusa!

O, eusova adotasmadna adami!

O, otasova a otasiuxat, ami agnonimento,

Ato adotaseusona, otasixa tun agranungel upakau.

Otasixolaus aser, uxteko! Otasova aser, uxteko!

O, eusixa ami aika!

O, ami ranedea upmenus adsped glos adato,

Asia ami ranagmenus onris agaga.

O, eusa!

O, eusmadi asaumesui!

O, otasiost adarsunmara ad adami,

Otasigevt a duqu adami ilato ami rolau.

O, eusa!

O, eusova adotasmadna adami!

O, otasova a otasiuxat, ami agnonimento,

Ato adotaseusona, otasixa tun agranungel upakau.

Otasixolaus aser, uxteko! Otasova aser, uxteko!

O, land!

O, spirit-land, my love!

O, how I desire to walk upon your golden shores,

as I walked (nostalgic) in ancient times.

O, land!

O, motherland (womb-like parent-place)!

O, all the islands of my rosiest nostalgia,

All loyalty and life of mine, to you i give.

O, land!

O, people-place of all my family!

O, all the people and all the tongues I remember then as now,

May all the spirits permit you to persist unto eternity.

All spirit-cycles as one, unbreaking! All people as one, unbreaking!

O, spirit-land, my love!

O, how I desire to walk upon your golden shores,

as I walked (nostalgic) in ancient times.

O, land!

O, motherland (womb-like parent-place)!

O, all the islands of my rosiest nostalgia,

All loyalty and life of mine, to you i give.

O, land!

O, people-place of all my family!

O, all the people and all the tongues I remember then as now,

May all the spirits permit you to persist unto eternity.

All spirit-cycles as one, unbreaking! All people as one, unbreaking!

Dictionary

Root Languages

Successor Languages

Spoken by

Common Phrases

- "Engva!" - "Hello!" (lit. "(I) greet (you)!")

- "Atodai e?" - "What is your name?" (lit. "who are you (formal)?"

- "(name) logux adami." - "My name is (name)."

- "Ami voden!" - "Goodbye!" (lit. "I wish (you) well!")

- "Ato soxa e?" - "How are you?" (lit. "Are you swimming?")

- "Upsoxa askorve" - "(to) do something foolish" (lit. "to swim like a bird")

- "Atodai ami niuret." - "With respect, I (will) teach you (about something)."

- "Ato ami aika." - "I love you."

- "Ula itobo!" - "That makes sense (to me)!" (lit. "It floats!")

- "Ato ilkorkra, ato stoda." - "Bear these circumstances with firm, stoic resolve." (lit. "Sculpt yourself from stone.")

- "Ami marti." - "I thank (you)."

- "Marti, ami kaung." - "You're welcome." (lit. "I hear gratitude.")

- "Isema!" - "Good job!" or "That was easy!" (lit. "How efficient/thrifty/practical!")

Common Female Names

Alis, Amber, Axara, Aia, Bet, Eirin, Euda, Inga, Ida, Irisa, Itlina, Kara, Kvidra, Laxa, Lupara, Mara, Marisa, Mei, Meri, Meryx, Mola, Naoka, Oia, Olara, Tara, Qanta, Renko, Vana, Vika, Viktara, Vonela

Common Male Names

Arxid, Aurus, Aurelius, Batori, Baurus, Ben, Dairon, Ed, Eidger Eosept, Iodex, Iutav, Irido, Lengi, Mairo, Niko, Olu, Qest, Qekov, Sadao, Stegu, Sten, Travin, Uigo, Vex, Vexan, Viktor, Vinsel

Common Unisex Names

Ren, Loi, Melo, Parda, Sol

Common Family Names

Arodur, Aurus, Axara, Axi, Batori, Dailaxis, Denobern, Golarex, Ivand, Kar, Muir, Kar, Kola, Lang, Lengi, Lord, Lok, Med, Noventi, Osana, Parda, Patra, Pulver, Ranoi, Renko, Riter, Sagan, Sandoxus, Sav, Sebrox, Soteli, Zin, Siu, Spet, Sung, Vipstead, Voiranoi

Family names are similar to given names, but are considered unisex for this purpose and are treated as somewhere the person is from. For example, Eqai Voiranoi would introduce himself as "Eqai adVoiranoi, ami logux."

Wow! This is so incredibly thorough. I wish I understood the art of making a language! Excellent job. I can tell a lot of effort went into this.