Heliography

When Sir Edwin Harlowe published the Principia Arcana, outlining the principles of Universal Magic, in 1687, it catapulted the study of magical theory to the forefront of academia. This did not mean that other fields ceased to be investigated - merely that they received less attention from the public, and from those scholars most eager to attract it. Still, a number of researchers continued to toil in laboratories, investigating the mundane phenomena of the world - and making breathtaking discoveries.

One such figure was Professor Everard Pennyman, whose studies on the nature of light and its interaction with various substances led him to develop the heliograph - a device for capturing images upon treated glass plates for posterity. He first demonstrated the heliograph publicly in 1818, and in the years since, it has been refined, improved, and begun to transform how the people of Albion see - and record - their world.

The Fundamentals of Heliography

It has long been known that light, when funneled through a small aperture and properly focused, can cast a photonic shadow within a darkened chamber - an inverted image of the world outside projected upon the interior. Some explored the use of lenses to sharpen this image, and the phenomenon was regarded as an intriguing, though ultimately impractical, demonstration of natural principles.

Likewise, it was understood that certain substances reacted to light, changing color and properties upon exposure. But it was Professor Everard Pennyman who brought these two areas of study together to create the heliograph. By focusing light from outside a sealed compartment onto a specially treated glass plate, he succeeded in capturing the image - then fixing it in place with an additional chemical treatment, allowing it to be displayed in sunlight without being immediately obliterated.

The heliograph demonstrated by Professor Pennyman in 1818 was large, cumbersome, and slow - but it nonetheless amazed those who witnessed it. While Magic had introduced many wonders into the world, the ability to capture an image was not among them. Indeed, it seemed that no one had ever attempted to use Magic for this purpose.

In the twelve years since that first demonstration, numerous individuals have built upon the professor's original design. Notably, the introduction of the Halberd lens - invented by Amelia Halberd in 1828 - has dramatically improved image quality while halving exposure times. This, combined with advances in the chemical emulsions used to capture and fix the image, has transformed heliography from a scientific curiosity into a thriving industry, with hundreds of studios now operating across Albion and the continent.

Heliographic Applications

While some early commentators scoffed at the idea of practical heliography, many others saw its utility immediately. The Lundeinjon Metropolitan Police Force has adopted the heliograph for documenting crime scenes and capturing images of criminals to be distributed as needed. Natural philosophers have embraced the device for its scientific merits, using it to create images for textbooks and academic publications. While it cannot yet capture motion, it is excellent for documenting anatomical details during dissection.

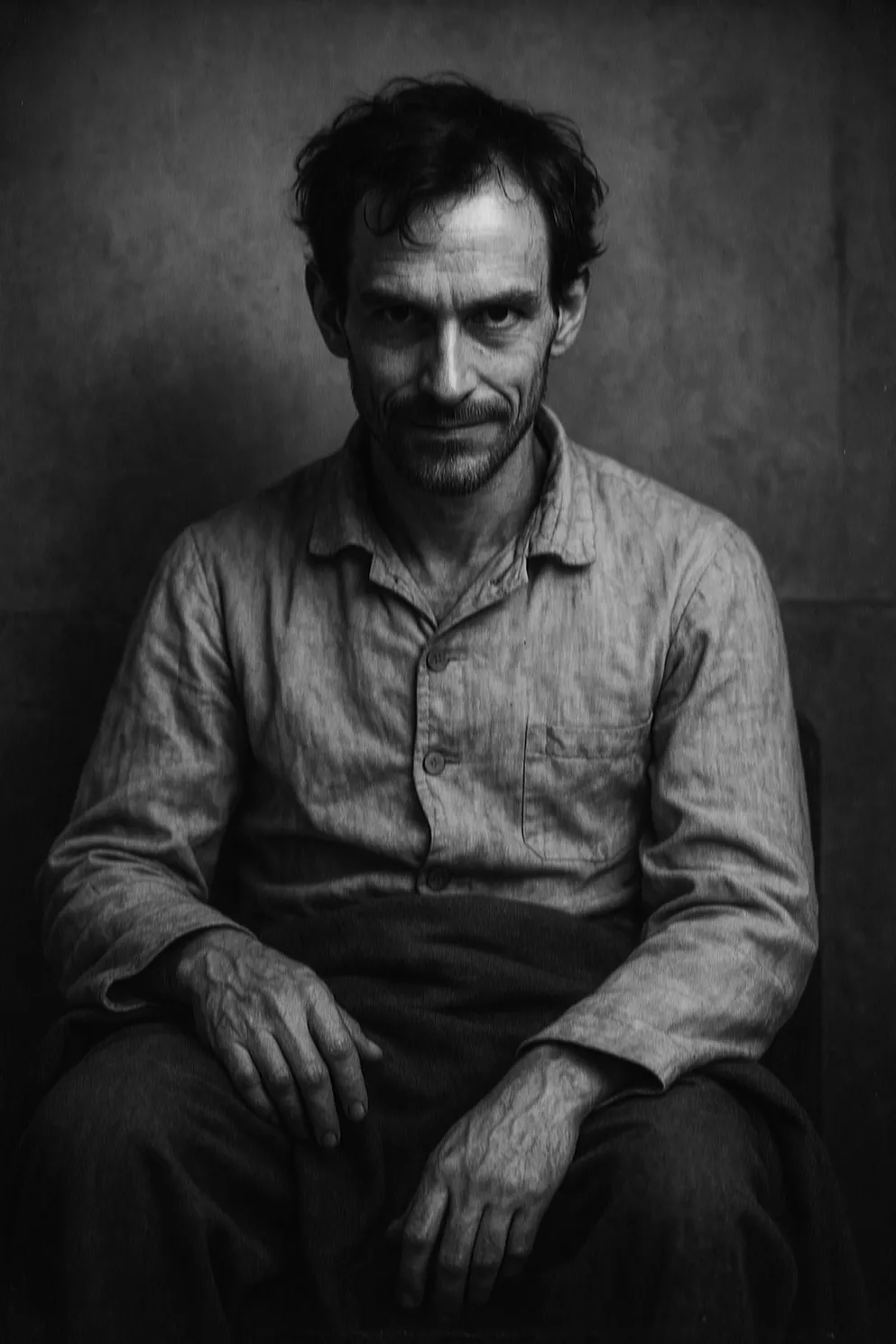

Personal portraiture has also become popular - though some dismiss it as a passing fad. Many heliographic studios make their entire living from the practice of thanagraphy: recording the likenesses of the dead prior to burial.

Others have begun to explore the heliograph's more unusual capabilities. Some artists use the long exposure time to their advantage, creating images that convey motion in ways never seen before. A few experiment with multiple exposures to illustrate change over time - Dr. Barbicane’s images of the moon's phases, captured over several nights on a single plate, are rightly celebrated for both their beauty and educational value.

As the technology continues to improve, many speculate about future applications. One popular author has proposed a kind of heliographic flipbook, in which multiple images taken rapidly might produce the illusion of motion. Others look ahead to lenses capable of capturing the very small or the very distant - opening avenues of research long considered inaccessible. While microscopes and telescopes have existed for years, the ability to record what they reveal, with the clarity of heliography, would represent a significant leap forward.

And all who study the arc of heliographic progress agree on one thing: the device's speed is improving. Soon, it may take only seconds to capture an image - making it easier than ever before to record the moment as it happens.

Controversy & Scandal

There are many who oppose the use of the heliograph, for a variety of reasons. Artists - particularly portrait painters - rail against the device as destructive to their art and livelihood. They claim it steals the image from the world and offers nothing of the depth, nuance, or humanity that a skilled hand can provide. Others go further still, asserting that it steals more than just an image - that it draws some vital essence from its subjects, leaving them vain, hollow, or diminished after repeated exposures.

Moralists decry the growing habit among young people - especially young women - of having their heliograph taken on special occasions. They denounce it as an act of vanity and pride to possess so many images of oneself - sometimes as many as two or three a year. Such behavior, they warn, encourages narcissism and a dangerous obsession with one's appearance.

Five years ago, a scandal shook the heliographic world and gave critics ample ammunition. Given the long exposure times, it had become common practice to immobilize subjects using mechanical restraints or paralytic magic to help them remain perfectly still during the process. Rumors soon spread that some heliographers were abusing this immobility - taking liberties with their subjects, or capturing images no decent person would have permitted.

The allegations were extremely damaging to the budding industry. The Albion Mirror published numerous letters demanding that heliographic studios be banned - along with a few asking that the evidence be released to the public, particularly the heliographic evidence itself. An investigation followed, but no formal complaints were ever filed. Whether no such incidents occurred, or victims were too ashamed to come forward, remains uncertain. A number of lewd images were indeed confiscated, but all appeared to have been taken with the subject's enthusiastic consent.

Still, a faint reputation for depravity and impropriety has clung to heliography ever since - though ironically, this has only increased its popularity, albeit with a rather different clientele than before.

The Future of Heliography

Despite its critics, the prevailing belief is that heliography is here to stay - and that it will, in time, transform the world. Some point to the social changes it brings, for better or worse. Others speculate about entirely new art forms: images shaped by the manipulation of light, time, and exposure, or the far-fetched notion of moving pictures created from a rapid sequence of still images.

What all agree upon is this: the images captured through heliography will become an ever more integral part of life in Albion and beyond - for as long as people wish to preserve light and memory. In other words: forever.

Light and the Heliograph

The term heliograph refers to images created by the light of the sun. Over time, however, many other forms of light have been introduced into the process. While none of these lesser lights compare to sunlight - and all produce inferior results - some speculate that this may change in the future. A few have even suggested that the name might evolve from heliograph to photograph, though Professor Pennyman has vehemently rejected any such notion.

On a bright, sunny day, a typical heliograph can be captured in three to five minutes - a vast improvement over earlier exposure times. On cloudy days, the process may take up to fifteen minutes and results in a more muted image, which some heliographers actually prefer for portraiture.

Candlelight, firelight, and gaslight can also be used to produce heliographs, but the required exposures are extremely long - often several hours if the light is dim. These sources are primarily employed for artistic purposes and are rarely used with live subjects. Still, firelit heliographs of ancient monuments have gained some popularity for their dramatic and haunting aesthetic.

Natural moonlight is another light source best suited to artistic work rather than accurate documentation. Exposure times are long, and the resulting images are typically soft, dim, and slightly blurred.

Never attempt to capture an image by the light of the Eldritch Moon. Early experiments produced images in which the subject appeared twisted, inhuman - and moving within the plate. These heliographs have since been locked away by royal decree. Some called for their destruction, but it remains unclear whether that would banish the creature inside or set it free.

Magical light, oddly, does not register on the heliographic plate at all - the exposure remains entirely black. Some claim this reveals that the light produced by Magic is not truly light at all. What that means, however, remains hotly debated: after all, magical light clearly illuminates the world to the human eye - but not to the heliograph.

Occult Heliography

While heliography is a technological - not magical - invention, this does not mean it fails to interact with the occult. On the contrary, many have attempted to use it to explore the unseen world - with some success.

Interest in occult heliography began with two unusual phenomena. The first was the complete failure of heliographic plates to react to magical illumination. For reasons still unknown, magical light does not register on the plate at all.

The second, even stranger discovery, is the mirror effect. When a mirror appears in a heliograph, it does not reflect the room around it. Instead, it reveals a vast, dark space filled with distant stars and shadowy shapes. Many believe this depicts the realm Beyond, somehow drawn through the mirror onto the plate. Further experiments revealed that this only occurs with silvered mirrors; other reflective surfaces show nothing unusual.

These two effects triggered a surge of interest in the occult potential of heliography. Using alchemical emulsions and esoteric arrangements, occult heliographers claim to have captured:

- images of spectres and auras,

- glimpses of the past or future,

- a fleeting view of the face of God through a complex array of mirrors aimed at heaven.

Though most of these claims lack proof - the divine image reportedly dissolved over days, radiating heat too intense to approach - they have led to one verified discovery:

Heliographs cannot see glamours.

When aimed at a person or object cloaked in illusion - whether hidden or beautified - the heliograph ignores the magic and records the truth. The implications are profound. Many among the wealthy rely on glamours to enhance their appearance - yet the heliograph sees through them. Criminals and covert agents often use glamours to remain unseen - but in heliographs, they appear, if faintly, as blurred figures moving through the frame.

This has drawn serious interest from those in security and surveillance, and considerable alarm from those who depend on glamours for concealment or vanity. Among the latter, heliographs are now avoided with superstitious dread.

I think heliograph is a much cooler name than photograph. I really like how you have integrated this technology into your world, specifically in how it interacts (or doesn't) with magic.

Explore Etrea | WorldEmber 2025

Thanks! I had a lot of fun with this article.

Added to my reading challenge. :)

Explore Etrea | WorldEmber 2025