Coabey is the sacred realm of the honored dead — a Divine Realm nestled between twilight and starlight, where the ancestors dwell not in slumber, but in serene continuity. Governed by Maquetaurie Guayaba the Lord of the Dead, Coabey is not a realm of punishment or judgment, but of recognition and balance. Souls that reach Coabey have lived in harmony with the natural and spiritual world, and upon arrival, find themselves among kin — not only of blood, but of memory and essence. The realm pulses with ancestral wisdom, and its presence is felt across time, even as the paths to it have been sealed beneath centuries of disruption.

Landscape and Essence

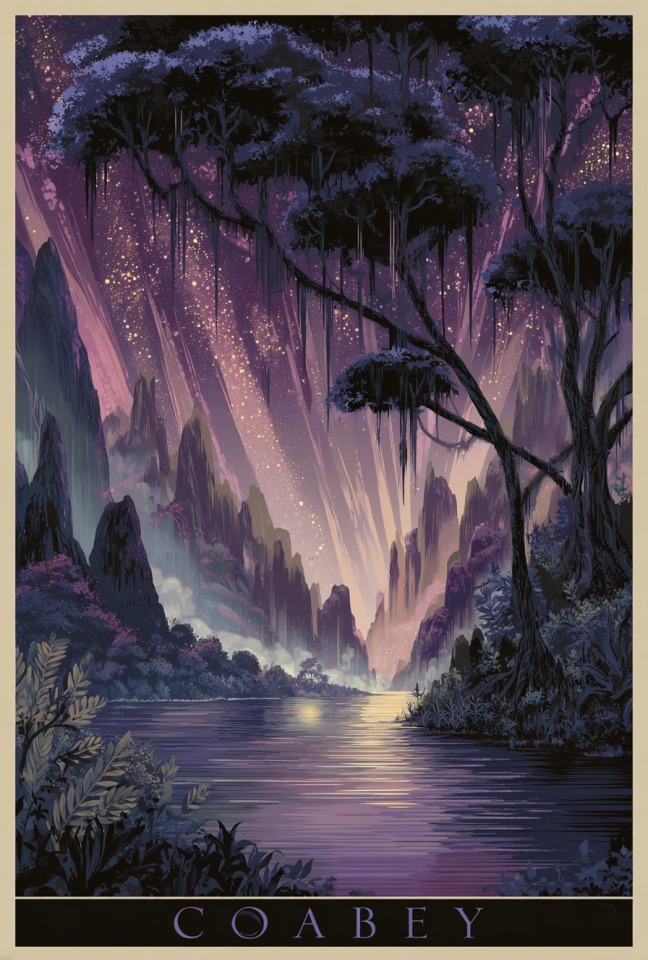

Coabey unfolds like a twilight grove resting on the shore of stars. It is neither day nor night — a permanent dusk streaked with violet and silver, where glowing rivers wind through forests that murmur with names once spoken. Great ceiba trees rise overhead, their roots touching water and their canopies etched with constellations. The air smells of sweet smoke, earth, and rain-washed stone. Gentle fires burn in circular hearths without consuming their fuel. The land sings in silence — a low, constant hum like breath shared among many. Coabey is not frozen — crops grow, crafts are made, and stories are retold — but nothing is rushed. All moves in the rhythm of memory.

Inhabitants

Coabey is home to the souls of the righteous dead — ancestors who lived in accordance with communal harmony, natural law, and spiritual resonance. These souls appear in their prime, though some choose alternate forms — animal, shadow, or light — depending on their role. Presiding over the realm is Maquetaurie Guayaba who governs not as tyrant or judge, but as steward and keeper. He moves quietly through the realm, tending to the flow of souls and guiding them into remembrance. Some souls remain only a while before rebirth or return; others linger, becoming spiritual protectors or messengers to the Mortal Realm.

Cultural Significance

To the Taíno, Coabey was a central part of the cycle of life and reverence. Death was not an ending, but a return to the ancestors, a rejoining of the great communal song. Rituals, burial practices, and ceremonial dances all reflected a belief in Coabey’s presence. Areytos — communal storytelling and song — served not just to honor ancestors, but to nourish the realm itself through memory. Caves, considered wombs of both life and death, were understood as points of passage between Coabey and the Mortal Realm. The coming of colonizers, the suppression of Taíno identity, and forced conversions fractured the rites — but Coabey endured in whispers, dreams, and the quiet return of names.

Role in the Divine Realm

Coabey serves as the ancestral sanctuary of the Divine Realm — a place where memory is not archived, but lived. It is the resting space of those whose lives added to the harmony of existence, and a buffer between mortal noise and divine resonance. Coabey keeps the line of the past intact — so gods, spirits, and mortals alike may look backward and remember who they are. Unlike realms of trial or judgment, Coabey requires no penance — only peace. It supports other realms by housing the stable dead the ones who do not wander, rage, or hunger. From Coabey, ancestral aid flows into dreams, healing, and divination.

Interactions with Other Realms

In earlier eras, Coabey was closer — accessible through caves, rivers, and sacred groves. Shamans and behiques entered trance to commune with ancestors, and certain rituals could even allow brief visitations. But as the Taíno world was torn apart by conquest and erasure, the paths narrowed. Coabey did not vanish — it withdrew. Now, only divine beings, and the rare living soul walking in perfect balance, may cross its veil. Still, its breath lingers in still water, in ancestral songs, and in dreams where the dead offer counsel with no words.