Grey Rot

"It is not the fire or the sword that humbles the world, but the quiet dust that waits beneath our feet, patient as the grave."

The Grey Rot is one of the oldest recorded plagues in the world’s memory. It was not born from the gods or from magic but from the soil itself. Long before kingdoms rose or scholars named their sciences, it swept across the continents and left whole generations buried in ash. It began as a harmless dust that clung to crops and skin, carried by wind and water. The first to fall were those who lived close to the ground, the farmers and herders who drew their breath from the same earth that would later consume them. The first signs were mild. Grey patches appeared on the skin, dry to the touch and without pain. Within days the flesh beneath hardened, then softened, then split. There was no bleeding, only a slow collapse as the body forgot its own warmth. When the rot reached the lungs, the breath turned to dust. Victims would cough until their voices vanished, leaving only a faint grey residue where they lay. Nothing stopped it. Herbs, poultices, prayer, and spellcraft all failed. In some places healers tried to cleanse the flesh with magic and found the sickness spread faster, as if feeding on the attempt. Priests refused to bless the dying, afraid that even mercy would carry the taint. The Rot seemed to consume both faith and reason, leaving behind a silence that no one could name. Cities fell without fire or war. Markets closed, temples emptied, and fields turned to stone where the dust settled. The air itself seemed heavy. People spoke of tasting metal on their tongues, of seeing light bend strangely around the infected. Travelers carried the spores unknowingly, their clothes greyed at the seams before their bodies followed. Whole valleys were burned to stop the spread, and the smoke of their sacrifice blackened the sun. When it finally passed, no one could say why. The survivors built new homes on the bones of the old and vowed never to forget. The word for cleanliness in several tongues still means free of grey, and the oldest burial laws forbid the keeping of soil from the graves of the dead. The Rot became myth, a warning that life itself could betray those who trusted it too deeply. Centuries later, its traces still appear in sealed caverns and forgotten ruins. When miners strike a seam of old air and cough up dust that tastes of iron, work stops. Tunnels are filled, fires lit, and prayers whispered to no god in particular. The same fear rises each time, old and immediate, as if the world remembers before reason can catch up. No one knows if the Rot ever truly died. Some claim it only sleeps in the deep rock and wakes when disturbed. Others believe it lingers in the air above places where too much blood has been spilled. Whatever its truth, it remains one of the few ancient terrors that neither science nor sorcery ever tamed. The people of Aerith still speak of it in half remembered phrases. To go pale is to walk the Grey Path. To breathe dust in your dreams is to hear the soil whisper. They treat those words lightly in peace and very carefully when the wind carries a smell that should not be there.

Transmission & Vectors

"It rides the wind like a memory. You do not see it, you only breathe and by then, the world inside you has already begun to change."

The Grey Rot spreads through contact with its spores, which form an invisible dust that drifts on air and clings to skin, hair, and cloth. It is most dangerous in dry climates or enclosed spaces where wind cannot disperse the particles. The fungus thrives in soil rich with organic decay, and its first hosts were likely animals that grazed near infected ground. Once disturbed, the spores rise and remain suspended for hours, entering the body through breath or open pores. Contaminated food or water can spread the sickness as well, though this is slower and less common. The disease becomes infectious long before symptoms appear. The body begins shedding spores within a day of exposure, even as the host feels healthy. This silent period allows the Rot to move quickly through crowded settlements, caravans, and ships. By the time visible greying of the skin begins, the surrounding environment is already saturated. Touching a victim, their clothing, or even the dust that collects near their bedding carries the same risk as breathing beside them. Rain or deep cold can suppress transmission, but only for a time. The spores remain dormant until conditions favor them again. They have no natural predator and no known limit to their survival. In every age that has recorded its return, the first cases always begin with someone disturbing ground that should have been left alone, or breaking a seal that time had built for a reason.

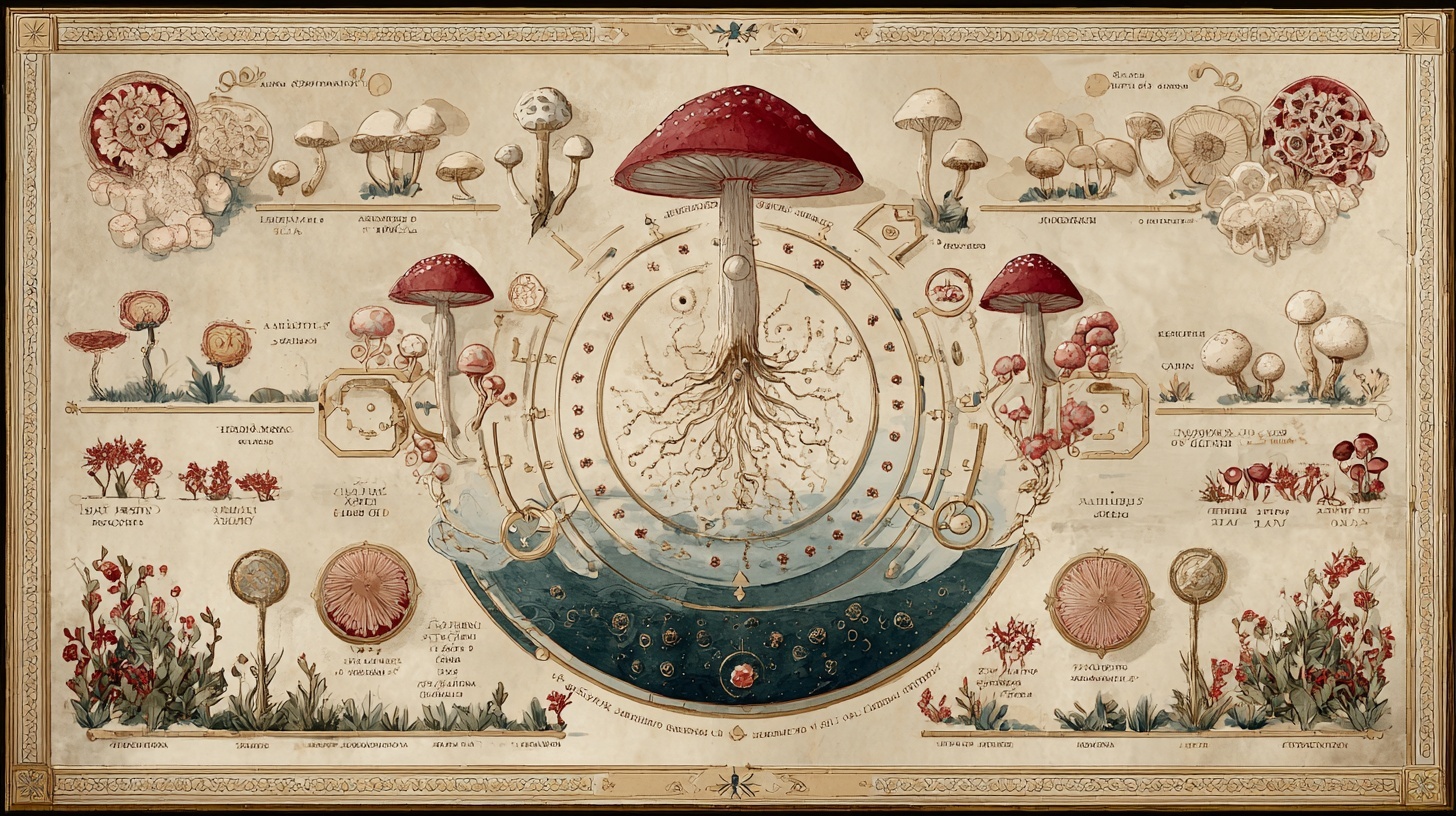

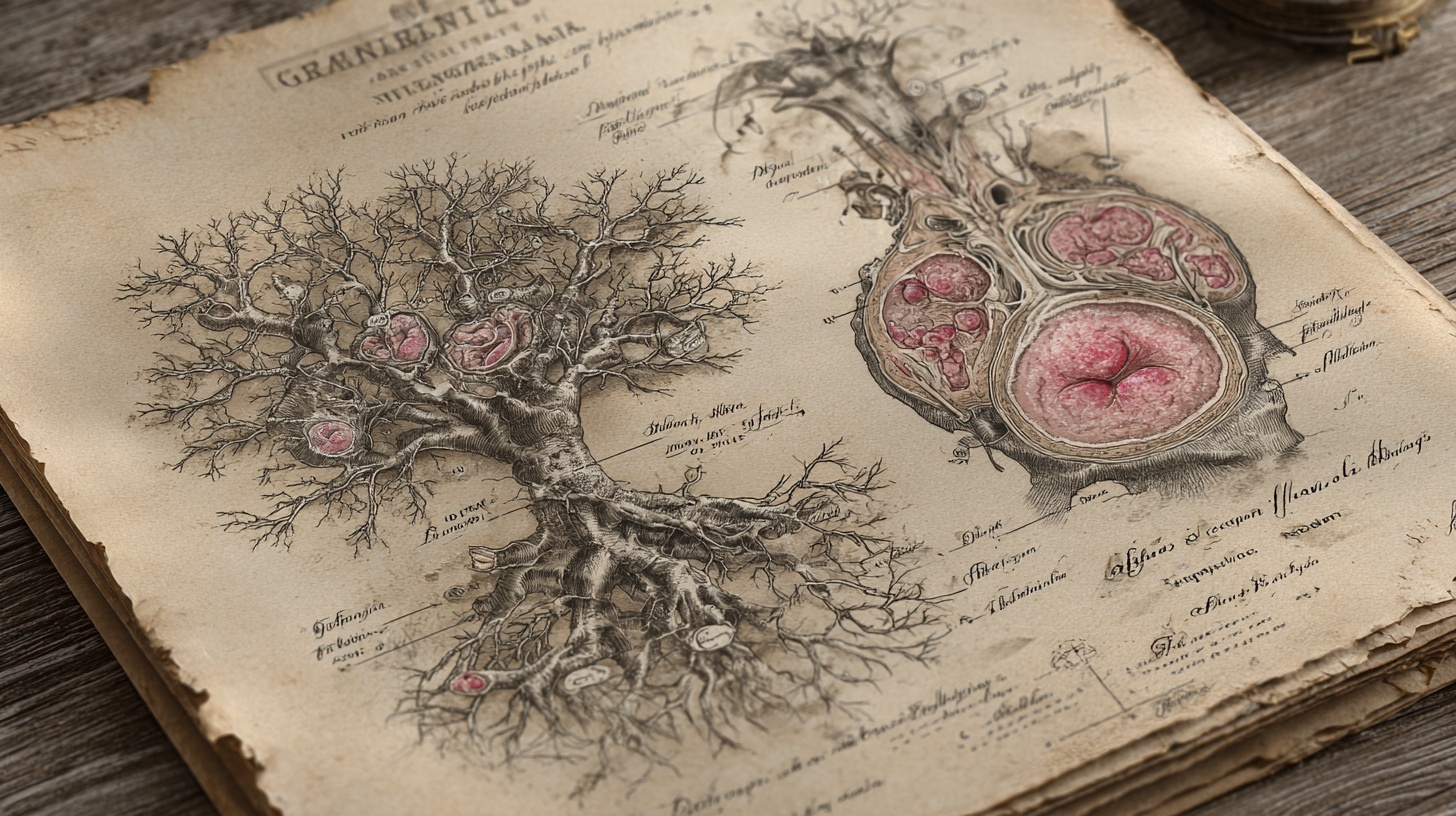

Causes

"The Rot does not live as we do. It remembers. It sleeps in stone, drinks light, and when it wakes, it hungers not for flesh, but for the warmth that proves we are alive."

The cause of the Grey Rot lies in a subterranean fungus that predates known civilization. The organism survives as a network of thin filaments buried deep within mineral-rich soil. It remains dormant for centuries at a time, feeding slowly on trace organic matter. When exposed to warmth, moisture, and dead tissue, it blooms. The fungus produces an immense quantity of microscopic spores that resemble fine grey ash. These spores are both light and resilient, able to float for miles in calm air or cling to clothing for weeks. Even a small disturbance in an ancient tomb, mine, or battlefield can release enough to infect an entire community. The spores are not alive in the way most living things are understood. They can survive extremes of heat and cold that destroy ordinary fungi. Scholars who have studied preserved samples describe them as crystalline rather than organic, suggesting a mineral bond within their structure. This may explain their endurance, as well as their attraction to magic and vital energy. Wherever blood or power has been spilled, the Rot finds fertile ground. The organism appears to metabolize not only flesh but the faint residual charge left in living tissue. This makes it uniquely adaptable and nearly impossible to starve. When inhaled, the spores enter the lungs and attach to the inner lining where they begin to grow. Their threads spread through the bloodstream, feeding on iron and breaking down connective tissue. The body’s immune response is slow to recognize the invasion because the spores mimic the mineral content of the host’s own bones. This deception allows the infection to progress unnoticed for several days. The skin then begins to lose color as oxygen levels drop, and the flesh takes on its signature grey hue. Environmental conditions play a critical role in the life cycle of the Rot. It flourishes in damp stone, decomposing plant matter, and stale air. Excavations that cut into ancient rock or unearth forgotten structures often trigger outbreaks. Heavy rainfall or flooding can expose dormant colonies, while volcanic activity or mining can heat the soil enough to awaken spores trapped far below. The Rot does not spread easily through open plains or windy regions, but it thrives in mountain vaults, catacombs, and valleys sealed by fog. The cycle begins and ends in the soil. When a victim dies, the fungus completes its work by breaking the body down entirely into dust, leaving only traces of calcium and a fine powder that blends back into the ground. Each death adds more spores to the earth, which harden into dormancy until disturbed again. The world itself becomes the carrier, preserving the disease in layers of stone and memory. In this way the Grey Rot outlasts every cure and every civilization that has ever tried to bury it.

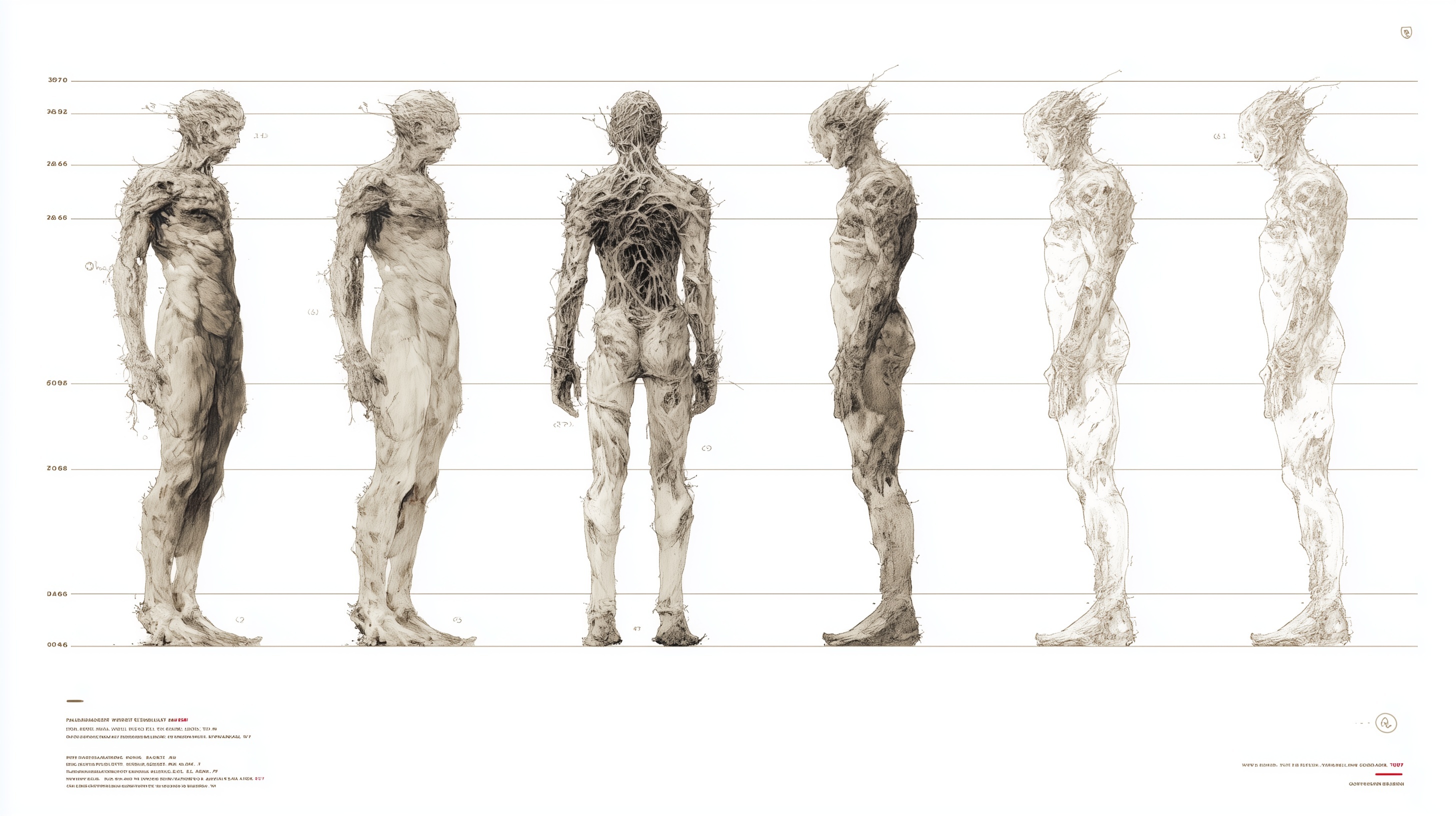

Symptoms

"The body forgets itself first. The heart goes silent, the blood forgets to move, and the soul begins to wonder if it still belongs here."

The first signs of the Grey Rot are subtle and easily mistaken for exhaustion or malnutrition. Within a day of exposure, the victim feels a dull fatigue that sleep cannot ease. The skin takes on a faint pallor that worsens in low light, and the breath becomes shallow. A faint metallic taste lingers on the tongue, often described as dust or rust. Coughing begins soon after, dry at first, then soft and persistent, as if the lungs are coated with fine powder. There is no fever and little pain, which makes the illness seem harmless until it is far too late. As the fungus spreads through the bloodstream, the body begins to lose color and warmth. The skin greys and dries, first on the hands and face, then across the limbs. Hair dulls and falls out in clumps. Fingernails lift from their beds and crumble. The flesh beneath becomes numb, then unresponsive, as circulation collapses. Cuts do not bleed, and bruises do not heal. Many infected describe a strange quiet in their bodies, as if the pulse itself has forgotten to move. The internal decay advances faster than the outer signs reveal. The lungs fill with thin grey mucus, and breathing grows slow and labored. The heart weakens, its rhythm softening until it beats only a few times each minute. When opened by healers or scholars, infected organs show a pattern of uniform desiccation. Bone marrow turns to powder, and veins appear etched in silver grey lines beneath the skin. At this stage, the body begins to release spores with every exhale, making the victim as contagious as the ground that spawned them. Mental symptoms follow as oxygen and blood flow decline. Victims become detached, quiet, and strangely calm. Some report hearing low murmurs in the back of their minds, a sound like distant wind or shifting sand. These whispers are not voices but the result of auditory hallucination caused by neurological decay. In the final hours, this detachment deepens into an almost meditative stillness. Victims stop responding to light, sound, or touch. Their eyes glaze to a dull stone color, and they lie motionless until the body finally collapses. Death from the Grey Rot is not dramatic. There are no convulsions or cries. The infected simply stop breathing, their flesh sagging inward as the fungus consumes the last of its host. Within hours, the body turns brittle and begins to crumble. A thin cloud of grey dust rises and disperses into the air, invisible but deadly. The smell that follows is faint and cold, like rain on stone. Those who have witnessed it say it is the quietest death in the world.

Treatment

"We called it mercy, but mercy burns the same as fear. When the fire takes them, we pray only that the ash remembers kindness."

There is no known cure for the Grey Rot. Once the spores take hold, the body becomes their soil. The fungus anchors itself too deeply to be cut out, and no medicine can reach the threads that feed on blood and bone. The only reliable form of control has always been isolation and fire. In every age where it has returned, victims are quarantined far from settlements, their remains burned before the body collapses to dust. It is not mercy so much as necessity. Healers have attempted countless remedies over the centuries. Mixtures of mercury, ash, silverleaf, and vinegar have been brewed to draw out the infection. Steam baths, cauterization, and bleeding were all tried in desperation. At best these measures slowed the progress for a short time. At worst they spread the rot further through the bloodstream. Even alchemical tonics and restorative magic proved useless. Spells that mend flesh seem to quicken the fungus rather than hinder it, forcing every healer since to abandon enchantment as a cure. Some cultures experimented with fumigation, sealing victims in stone chambers and flooding the air with burning resins or chemical smoke. When attempted early, this treatment occasionally stopped the spread across the skin, but the toll was severe. Survivors were left scarred, their lungs weakened, and most died within months. The ingredients for these fires were rare and costly, often demanding resources that could have fed entire villages. It became a desperate act, reserved for nobles or those who could afford to fail. Preventative customs vary from one land to another, though most involve heat, dryness, and ritual purity. Fresh graves are burned rather than buried, dust is swept from homes before sunrise, and wells are sealed after any death. Masks of waxed cloth are worn when working with old earth, and travelers wash in salt water before entering cities. These traditions endure not from science but from the memory of what happens when they are ignored. Because the Grey Rot cannot be healed, treatment means only comfort and containment. The infected are kept warm and given mild sedatives to ease their breathing. When the numbness takes hold, they are left in quiet until the end. Once the body stills, it is burned before the first hour of dawn. The ashes are buried under clean soil, and the site is sealed with stone. No prayers are offered. The act itself is the prayer, one repeated across ages whenever the dust begins to rise again.

Prognosis

"They do not scream. They fade, as if the world itself has drawn a long breath and forgotten to let it go."

The course of the Grey Rot is relentless. Once the spores enter the body, no treatment can halt their growth. The infection progresses in measured stages that seldom vary, making its rhythm as familiar to healers as it is horrifying. The first stage lasts one to two days. Fatigue and pallor set in as the lungs and blood begin to fail. The victim may still walk, speak, and eat, though their voice grows thin and dry. During this time they are already infectious, releasing spores with every breath. The second stage begins when the skin greys and hardens. Circulation falters, and the body cools. Sensation fades from the extremities, followed by a steady loss of strength. Within a few days, the victim’s breath shortens to a shallow rasp, and the cough turns to dust. The mind remains clear even as the body collapses. Many sufferers report feeling as if they are sinking or fading away, aware of everything but unable to move. This stage lasts from three to five days, depending on the health of the host. The final stage comes quietly. The body no longer recognizes itself as living. The pulse slows to almost nothing, and the flesh dries and splits. The victim’s last breaths release a thin cloud of spores that settle into the nearest surface, ensuring the cycle begins anew. Within hours the remains crumble to dust, leaving a residue that can linger for years if not burned. Death is inevitable. There are no cases of recovery and no known immunity. Despite its horror, the Grey Rot does not lead to undeath or reanimation. Once the host perishes, nothing of the person remains. The fungus feeds until there is nothing left to consume and then turns dormant. Some claim that the calm that overtakes the dying is a sign that the mind surrenders before the end, but this is superstition, not resurrection. The Rot gives nothing back to the world. It only waits for its next chance to be disturbed.

Epidemiology

"Every age finds its own way to dig too deep. Every empire builds on the bones of another, and still we act surprised when the earth exhales."

The Grey Rot moves across species as easily as it does across borders. It does not distinguish between mortal kind, beast, or fey. Any living body that breathes, sweats, or bleeds can harbor its spores. Humans spread it fastest through trade and travel, but elves, dwarves, and tieflings have all carried it into their own lands. Even the long lived races, who once believed themselves immune to common illness, found the Rot creeping through their cities when contact with outsiders became frequent. The fungus thrives wherever there is life and warmth. It ignores bloodline, faith, and magic alike. The first outbreaks often begin in places where races mingle. Border markets, mercenary encampments, and port cities become flashpoints. Caravans carry spores on cloth and fur, while animals used for transport become mobile reservoirs of infection. Shifters, tabaxi, and other beast-kin are especially vulnerable, as the spores can cling to fur and scales for weeks. Elves and dwarves tend to incubate the disease longer before showing symptoms, which makes them silent carriers during early stages. Only constructs, undead, and elementals appear wholly immune. Environmental conditions amplify the spread. Dry, windy plains carry the spores farthest, while underground settlements provide the still, damp air the fungus loves most. During heat waves or drought, the air grows heavy with fine dust that can keep spores active for months. Great migrations, spring festivals, and wartime campaigns have all served as the spark for continental pandemics. Even races who dwell far apart, such as aarakocra or tritons, have recorded isolated outbreaks brought by travelers or relics unearthed from ancient ground. Each resurgence begins with a single act of disturbance. A dwarven excavation breaks into a forgotten vault. A dragon’s landing stirs ancient soil. A war mage’s bombardment turns the earth itself to powder. The spores rise unseen, carried on wind, fur, and feather. Within weeks the sickness crosses every border. No barrier of race or realm holds it back. It moves wherever life does, following the same roads, rivers, and trade routes that once connected the world.

Comments