The True Tale of King Perseus

Act I: The Castaway and the Sky

Long ago, in the sun-bleached halls of Argos, King Acrisius sat upon a throne he believed cursed. For all his wealth and power, he had only one child—a daughter, Danaë. To Acrisius, this was not a gift but a cosmic insult. A son would have been a legacy; a daughter, in his eyes, was a mistake.

Danaë was brilliant. Beautiful. Curious. And utterly wasted in the gilded cage of her father’s ambitions.

Acrisius' frustration festered into fear when the Oracle spoke:

“You will die by the hand of your daughter’s son.”

Kings such as he are rarely known for their emotional resilience, and Acrisius was no exception. He consulted witches and warlocks, shamans and snake-oil seers. He tried every method known and whispered to seal his daughter’s womb—rituals, curses, even rare herbs picked under blood moons.

When that failed, he turned to brute cruelty.

Danaë was locked away in a tower hidden deep in the palace. Stone walls,Bronze bars, and only her maidens or Enuchs for company. Her future was shackled. Her joy smothered. Her very body treated as a time bomb wrapped in silk.

Alone and grief-struck, Danaë cried—not for rescue, but simply to be heard. And someone did.

From Olympus, Zeus—King of the Gods, serial romantic, professional shapeshifter—heard her sorrow. He came to her not as a brute-force thunderbolt, but as a breeze, a bird on the sill, a shimmer of golden rain through the cracks in the stone. Companion first. Lover second. For Zeus always fell in love easily with extrodinary women and Danae was a woman of rare beauty, grace and spirit.

No mortal curse could thwart divine essence.

Danaë became pregnant. And when Acrisius discovered the child, his terror exploded into fury. He nearly struck her down—until the sky split open with thunder.

“If you harm Danaë or the child of my blood,” Zeus roared from the heavens,

“the Erinyes shall descend upon you, and your torment legendary.”

Acrisius, was never brave and when thunder rolled, he backed down. But wicked cowardice breeds creativity.

Unable to kill them outright, he ordered a coffin-shaped boat be built—long, narrow, and watertight. He packed Danaë and her newborn son inside, gave them a few days’ food and water, and cast them into the open sea.

He told himself the gods would decide their fate. In truth, he hoped Poseidon would be hungry that day.

But Danaë was not so easily undone.

Whether by the divine will of Zeus or sheer mortal tenacity, she weathered the waves. She rationed her food. She rocked her crying child. She prayed to every god with ears—and some without. And in time, their battered coffin washed ashore on the island of Seriphos, where they were found by a fisherman named Dictys.

Dictys, brother to the local king, was no noble. Just a man of honest work and rough hands. But he took them in—mother and child—and gave them shelter and dignity where a king had given only fear.

And so Perseus was raised not among kings, but in salt spray and starlight. A demigod born of prophecy and pain, cradled in exile, fed on kindness and sea-wind.

The world had no idea what storms he would bring.

Act II: The King’s Trap

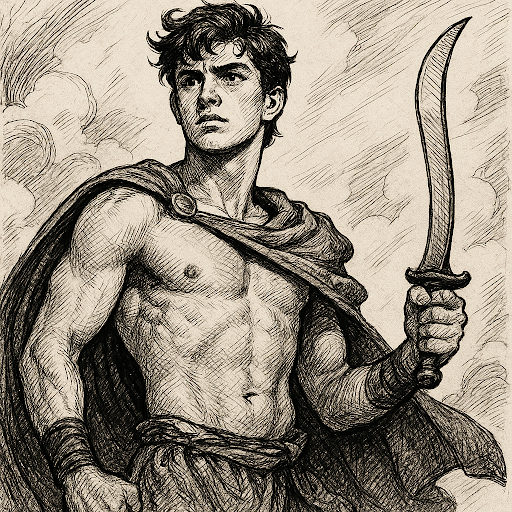

Years passed on Seriphos, and Perseus grew strong—stronger than most boys, quicker than most men. He could haul in nets no child should lift, and even the gulls seemed to respect his aim with a sling. But what made him remarkable wasn’t his divine blood or uncanny speed. It was his devotion.

He loved his mother fiercely. And Danaë, for all she had endured, raised him not as a prince, but as a good man. This did not go unnoticed.

The King of Seriphos, Polydectes, was a man who collected beauty the way pirates collected gold. He admired Danaë’s grace, Perseus’s strength—and he wanted one but feared the other.

He tried wooing Danaë with gifts and compliments, but she rebuffed him with polite disdain. She’d been seduced by a god; what hope did a sunburnt despot have?

Polydectes, insulted and humiliated, turned his attentions elsewhere—publicly.

“I shall marry the fair Hippodamia!” he announced to the court one evening, smug as a cat fat with lies. “But of course… a king needs wedding gifts.”

Every man in Seriphos was expected to bring a horse. A fine tradition, except for one detail: Perseus owned no horse. He and his mother had barely survived on fish and kindness. They had no gold, no land, and certainly no stable.

Polydectes knew this.

It was a trap, and everyone knew it except Perseus.

But instead of shame or excuses, the boy stood proud and said:

“I have no horse to give, my king… but if you would ask for a greater gift, name it, and I shall bring it.”

The room fell silent.

Polydectes smiled a smile that had no warmth in it.

“Then bring me the head of Medusa, the Gorgon.”

Gasps followed. Laughter. Then silence again. Even the guards shifted uncomfortably.

Everyone knew the tale. Three sisters, born before the gods themselves. Stheno—the strong. Euryale—the winged. And Medusa—the youngest and most beautiful, cursed by wrath. Snakes for hair. Eyes that turned men to stone. A death so swift it made beheading her seem generous.

Polydectes thought he had won. A boy against a legend? It would be a death sentence disguised as a quest.

But Perseus only nodded.

“Then I shall return with her head.”

Foolish? Perhaps. Brave? Absolutely. And somewhere, high on Olympus, Athena opened one eye with interest.

The game was on.

Act III: The Garden and the Gorgon

Medusa and her immortal sisters—Stheno and Euryale—were known as Gorgons: monsters, or so the world insisted. They were said to wear serpents for hair, bear fangs like beasts, wings of burnished gold, and eyes that turned the living to stone. Perseus knew none of this.

According to King Polydectes, they were just a nasty trio of snake-women who preyed on the weak. Nothing a good sword swing couldn’t fix.

Before setting out, Perseus did what any well-meaning (if dimly clever) demigod does: he made a sacrifice. A bull, to be specific. Most of it he ate—he was a growing boy with heroic metabolism—but the heart and bones were offered to Zeus, along with a heartfelt prayer for guidance.

Zeus, who hadn’t stopped caring for Danaë or the boy she'd raised with salt wind and grit, didn’t respond directly. But he did send word up Olympus:

“Any of my divine children want to help their little brother not die?”

Athena answered first. Purposeful, quiet, calculating. She had her reasons.

Hermes answered second. He thought it might be amusing—and besides, he liked the kid. Bit thick, but earnest.

Hermes appeared first, in a gust of wind and wit. He brought Perseus two things: his own winged sandals, and—less ethically—Hades’ Helm of Darkness, which Hermes had “borrowed.”

“Thievery,” he explained, “is just aggressive borrowing.”

Then came Athena, gleaming and grave. She gave Perseus her mirror-polished bronze shield.

“Do not meet her eyes,” she warned. “Let her reflection be your only truth.”

She also handed him a kibisis—a god-woven bag designed to contain the severed head of a still-cursed Gorgon.

“Even in death, her power will linger.”

Finally, she gave him a quest: seek the Graeae, the witches who knew where the Gorgons hid. Then find the Hesperides, guardians of the Herpe—a blade honed to sever divine flesh.

So, Perseus set out.

He found the Graeae first—three ancient, bird-like crones who shared a single magical eye and a dragon’s tooth between them. Sisters to the Gorgons, and even less polite.

They mocked him. They threatened him. They dismissed him entirely.

So Perseus did something clever (for once). He slipped on the helm, turned invisible, and spied on them until they passed the eye from one clawed hand to another. Then—snatch. Eye stolen.

They shrieked. He offered a trade: directions to Medusa’s lair in exchange for the return of their magical sight.

Grumbling curses older than language, they told him: the Gorgons lived on the Isle of Sarpedon, a crumbling ruin surrounded by cursed gardens, petrified sentinels, and silence.

He left them their eye. Eventually.

Next, he sought the Hesperides—twilight nymphs who danced on the edge of the world and kept apples of gold and secrets sharper than blades. They gave him the Herpe, a blade forged in starlight, curved like the crescent moon and bound in silver. Weapon in hand, Perseus flew for Sarpedon.

The cavern was quiet.

Statues lined the halls—men frozen mid-motion, faces contorted in awe, terror, or pride. A garden of stone. A graveyard of ego. And then, in the reflection of Athena’s shield, he saw her.

Medusa.

Not roaring. Not monstrous.

Just... still.

Beautiful, cursed, and still. Serpents coiled across her shoulders like sighs. Her eyes—veiled—still shimmered with ancient pain.

She did not run. She did not scream. She looked into the shield’s reflection and whispered:

“Athena sent you.”

And Perseus—heart pounding, sword shaking—raised the blade.

“Thank you,” she said.

And he struck.

There was no dramatic scream. Just silence, and then the soft hiss of severed snakes slumping to the floor.

He placed the head gently into the kibisis. Even unseen, her presence lingered—like storm lightning after the flash.

As he turned to leave, something in the cavern shimmered—an object, tucked among ancient relics and scattered bones. A bridle, braided from gold and leather, adorned with polished sea-stone. Magical, no question.

Perseus, ever the practical looter, pocketed it with a shrug.

“Never know when a fancy horse leash might come in handy.”

That, of course, was the moment the house woke up.

Stheno and Euryale had sensed the theft, and unlike Medusa, they were not in a forgiving mood.

They descended like shrieking tempests—claws flashing, wings tearing the air, voices raw with fury.

Perseus did what most demigods would in that moment: panicked and fled.

He sprinted through the corridors of statues, sandals flapping, blade rattling at his side. And as Stheno nearly caught his arm with a hooked talon, he remembered—

“Oh right. The helmet.”

He shoved it onto his head mid-flight—and vanished.

Invisible now, he slipped through shadows, evaded furious shrieks, and finally—mercifully—escaped.

He did not look back.

Act 3.5 – That One About Atlas? Yeah, No

Greek storytellers will swear that after escaping the Gorgon’s lair, Perseus flew west, encountered the Titan Atlas, and, in a moment of divine judgment, turned the great being into the Atlas Mountains with a single flash of Medusa’s gaze.

That didn’t happen.

What did happen was this:

Perseus got drunk in a taverna while waiting for the next boat back to Seriphos and, while showing off, may have embellished the truth a little.

Or a lot.

The tale spread—as tales do—and poor Atlas, who had absolutely nothing to do with anything, ended up immortalized in myth as a mountain range. A very impressive mountain range, sure, but not exactly a willing participant.

Perseus would later protest, “Hey, it was a joke!” But by then the bards had already written the song, the vase painters had done their thing, and Atlas was a landmark.

Meanwhile, having clearly forgotten he was wearing winged sandals, Hence the boat ride, Perseus finally took a closer look at the bridle he’d lifted from Medusa’s lair. It shimmered with divine craftsmanship—sea-stone beads, golden etchings, and something distinctly mythic in its aura.

He ran his fingers along its surface—and the sky split with a thunderclap.

From the clouds descended Pegasus—the winged horse of legend, pure as moonlight and fierce as a storm.

“…Huh,” said Perseus, blinking. "Neat"

He did not tame Pegasus. He accidentally summoned him. Using a relic he barely understood.

But those who saw him soaring across the skies—hair wild, hero's bag slung at his side, divine steed beneath him—assumed, quite naturally, that he had done something epic to earn it.

Which brings us to Bellerophon.

He actually did tame Pegasus.

Slayer of the Chimera. Rider of legends. Noble warrior of Corinth. Thrown from Olympus for daring too high.

And to this day, even in the Elysian Fields, Bellerophon sulks.

Muttering, “That little brat stole my thunder…”

Act IV – A Date with Destiny (and Andromeda)

After barely surviving two furious immortal Gorgons, fleeing with a magical horse, and not turning a Titan into a mountain, Perseus did what any self-respecting demigod would do with the freedom of the skies at his feet:

He took a boat.

Why? No one knows. Maybe he thought Pegasus needed a break. Maybe he got airsick after flying. Maybe he just didn’t think too hard about it—his usual method.

In any case, the journey back to Seriphos didn’t go as planned.

The Queen, the Boast, and the Bureaucracy

His detour led him south to the coast of Ethiopia—a kingdom not currently enjoying its time in the spotlight. The trouble began when Queen Cassiopeia, blessed with beauty and unburdened by humility, made a catastrophic boast:

“My daughter Andromeda is more far more beautiful than the Nereids. Smarter, more skilled and a better singer!”

Now, the Nereids—Poseidon’s extended aquatic family—were known for their vanity, viciousness, and willingness to escalate petty slights into full-blown divine vendettas.

They complained.

Poseidon, already irritable and knee-deep in sea monster paperwork, gave a weary sigh and unleashed Cetus—a draconic leviathan—to remind everyone what happened when you insult sea nymphs.

Cetus tore through the coast like a natural disaster with scales, coils and fangs.

Desperate for a solution (and maybe an opening to seize power), the local oracle Ammon declared: “Only the sacrifice of Andromeda will soothe the sea’s fury!”

Nobody questioned this. Naturally.

Well nobody but Andromeda did. She did rather loudly. But no one listened.

She was chained to a seaside cliff in ceremonial silk, surrounded by trembling priests and very few answers. A princess turned scapegoat.

Enter: The Hero on a flying Horse

Fate—or terrible navigation—brought Perseus to her just in time.

He saw her first, lashed to the rock, face proud despite the salt wind. His heart skipped a beat, then another, then possibly forgot how to beat at all. She was radiant. Also endangered.

Andromeda, for her part, saw a shirtless stranger gawking at her from a boat and briefly wondered if death might be less embarrassing.

Then Cetus rose from the waves, all teeth and roaring vengeance.

Perseus knew then and there that it was Hero time.

Perseus snapped out of it, fumbled for the magical bridle, remembered the sword and the sandals, and vaulted onto Pegasus. In a flash, he was airborne, cloak flapping dramatically behind him like a man who planned this all along.

He didn’t, never did, he didnt have plans so much as tiny fragments of actual plans that sounded awesome in his head.

The fight was brutal. Cetus was no idle monster; he was divine punishment with scales and scalding steam for breath. Perseus took a beating—ribs cracked, tunic torn, a truly humiliating splash—but eventually, with one final, screaming dive, he buried the Harpe blade in the beast’s neck.

Victory.

Later, when asked about his strategy, Perseus would admit:

“…Honestly? I forgot I had Medusa’s head. Otherwise I'd just have turned Cetus to stone in one go”

But again—he looked amazing, so it was fine.

Andromeda the Wise

Once rescued and draped in an apologetic cloak, Andromeda did what most princesses in myths don’t—she asked questions. They talked. She learned quickly that Perseus wasn’t the brightest star in the heavens—but he was brave, kind, and capable of great things when properly motivated (usually by danger, snacks, or her smile).

He, in turn, was smitten. Not just by her beauty, but her sharp wit, her command of language, her subtle sarcasm when dealing with absurdity. A brain and a backbone? He was doomed.

He proposed.

She accepted, in what may have been one the shortest love stories in the ancient world.

Her parents, thoroughly relieved, gave their blessing. Oracle Ammon vanished under mysterious circumstances shortly after.

No one investigated. No one wept.

A Wedding and a Dowry

The ceremony was lovely.

Until Phineus, Andromeda’s original (and useless) fiancé, crashed it.

He waved around scrolls, shouted about promises, and made vague threats.

Perseus reached for his sword.

On pure acident the kibisis opened. Medusa’s head gleamed.

Phineus stopped shouting.

He also stopped moving. Permanently. One might say he struck a statuesque pose.

Home Again

With no further delays, the couple mounted Pegasus (who was still only mildly annoyed at being involved in any of this) and soared back to Seriphos.

There, they found King Polydectes mid-harassment of Danaë.

Andromeda, unflinching, simply said: “It’s time to give him his Dowry dear husband.”

Perseus, with all the dignity a vengeful son can muster, opened the kibisis one final time.

Polydectes joined the stone gallery, still reaching for Danaë in his final pose—forever remembered as a man who reached too far.

Dictys was crowned king.

Danaë was safe.

Perseus and Andromeda, finally free of monsters, curses, and tyrants, looked to the horizon together.

(Except Bellerophon. He still wont shut up about Perseus. But that’s another story.)

Act V – Prophecy, Mushrooms, and the Founding of Things

Perseus, ever the respectful borrower (at least when gods were involved), returned the magical artifacts he’d been loaned.

Medusa’s head went to Athena, who placed it with reverence upon her aegis. In return, she allowed Perseus to keep the harpe sword and the magical bridle of Pegasus.

And seeing as he also had Andromeda by his side, all in all, it was what a hero might call a “net gain quest.”

He planned to live a quiet life as the noble adopted son of King Dictys. Maybe grow olives. Raise kids. Possibly stop accidentally stealing other heroes’ myths.

But fate, as ever, had other plans.

The Deadliest Frisbee in Greece

Acrisius, King of Argos—and Perseus’ dirtbag grandfather—had not forgotten the prophecy: He would be killed by his own grandson.

Upon hearing that Perseus had not only survived but flourished, Acrisius panicked. Like any cowardly tyrant with a cursed grandchild, he ran off to Larissa, reasoning that distance and plausible deniability could thwart destiny.

Destiny, unfortunately, had a flair for comedic timing.

Larissa was just about to host a major athletic festival, and Perseus—ever eager to flex his demigod muscles—entered the games with Andromeda cheering him on and Danaë clutching her heart every time he so much as touched a discus.

During a heated match of quoit (think: discus, but with more collateral damage), Perseus unleashed a particularly mighty throw.

Right at that moment, Acrisius—blissfully unaware—stepped into its path.

He died instantly.

The prophecy was fulfilled.

The crowd went silent.

And Perseus was left standing there with the discus in one hand and a look that said, “Oh no. Not again.”

It was, as the poets later wrote, "the most underwhelming death by prophecy of the century."

Crimes, Crowns, and Clever Wives

By blood, Perseus could now claim the throne of Argos.

Unfortunately, Greek law—especially the “accidental patricide-by-sport” clause—was quite clear. Ritual exile, purification, and a public apology to the gods were required, regardless of how well-meaning your lethal frisbee had been.

So, in a move that surprised no one but impressed everyone, Andromeda negotiated a clean solution:

Perseus would trade the throne of Argos to his friend, Prince Megapenthes, in exchange for the nearby kingdom of Tiryns.

Two royal headaches solved. One PR disaster averted.

And not a single pitchfork-wielding mob to be seen.

City-Builder, Snake-Slayer, Mushroom-Namer

From his new seat in Tiryns, Perseus—alongside Andromeda—entered his “urban planning phase.”

Together, they founded the city of Amandra, later called Ikonion, eventually known to the world as Iconium (modern-day Konya). They also established the mighty city of Mycenae, which Perseus—over Andromeda’s very vocal objections—named after a mushroom he had seen and thought looked neat.

Later in life, Perseus went full founder-mode:

Defeated the Isaurians and Cilicians, as one does.

Built the city of Tarsus, thanks to an oracle that told him, “Build where your foot touches the earth as you dismount your horse.” As one also does.

Allegedly conquered the Medes, renamed the land Persia, and taught the local magi about the Gorgon’s power.

And once, when a fireball fell from the sky (possibly a meteor, possibly Dionysus being dramatic), Perseus allegedly caught the sacred flame and gifted it to the people.

That last one is widely considered a drunken tavern story, but it has a lovely fresco in the royal archives, so who's complaining?

Epilogue – The Perseid Legacy

Whatever the scholars say, Perseus became a legend.

He stood beside Cadmus and Bellerophon (who, it yet again must be said, still hasn’t forgiven him for the Pegasus incident) as one of Greece’s greatest heroes.

He was the son of Zeus and Danaë, and through his line would come Heracles—making Perseus both his great grandfather and half-brother.

Which, in Greek mythological family trees, is honestly pretty tame.

He fought monsters, toppled tyrants, outwitted witches (eventually), and founded cities that would stand for centuries.

Long ago, in the sun-bleached halls of Argos, King Acrisius sat upon a throne he believed cursed. For all his wealth and power, he had only one child—a daughter, Danaë. To Acrisius, this was not a gift but a cosmic insult. A son would have been a legacy; a daughter, in his eyes, was a mistake.

Danaë was brilliant. Beautiful. Curious. And utterly wasted in the gilded cage of her father’s ambitions.

Acrisius' frustration festered into fear when the Oracle spoke:

“You will die by the hand of your daughter’s son.”

Kings such as he are rarely known for their emotional resilience, and Acrisius was no exception. He consulted witches and warlocks, shamans and snake-oil seers. He tried every method known and whispered to seal his daughter’s womb—rituals, curses, even rare herbs picked under blood moons.

When that failed, he turned to brute cruelty.

Danaë was locked away in a tower hidden deep in the palace. Stone walls,Bronze bars, and only her maidens or Enuchs for company. Her future was shackled. Her joy smothered. Her very body treated as a time bomb wrapped in silk.

Alone and grief-struck, Danaë cried—not for rescue, but simply to be heard. And someone did.

From Olympus, Zeus—King of the Gods, serial romantic, professional shapeshifter—heard her sorrow. He came to her not as a brute-force thunderbolt, but as a breeze, a bird on the sill, a shimmer of golden rain through the cracks in the stone. Companion first. Lover second. For Zeus always fell in love easily with extrodinary women and Danae was a woman of rare beauty, grace and spirit.

No mortal curse could thwart divine essence.

Danaë became pregnant. And when Acrisius discovered the child, his terror exploded into fury. He nearly struck her down—until the sky split open with thunder.

“If you harm Danaë or the child of my blood,” Zeus roared from the heavens,

“the Erinyes shall descend upon you, and your torment legendary.”

Acrisius, was never brave and when thunder rolled, he backed down. But wicked cowardice breeds creativity.

Unable to kill them outright, he ordered a coffin-shaped boat be built—long, narrow, and watertight. He packed Danaë and her newborn son inside, gave them a few days’ food and water, and cast them into the open sea.

He told himself the gods would decide their fate. In truth, he hoped Poseidon would be hungry that day.

But Danaë was not so easily undone.

Whether by the divine will of Zeus or sheer mortal tenacity, she weathered the waves. She rationed her food. She rocked her crying child. She prayed to every god with ears—and some without. And in time, their battered coffin washed ashore on the island of Seriphos, where they were found by a fisherman named Dictys.

Dictys, brother to the local king, was no noble. Just a man of honest work and rough hands. But he took them in—mother and child—and gave them shelter and dignity where a king had given only fear.

And so Perseus was raised not among kings, but in salt spray and starlight. A demigod born of prophecy and pain, cradled in exile, fed on kindness and sea-wind.

The world had no idea what storms he would bring.

Act II: The King’s Trap

Years passed on Seriphos, and Perseus grew strong—stronger than most boys, quicker than most men. He could haul in nets no child should lift, and even the gulls seemed to respect his aim with a sling. But what made him remarkable wasn’t his divine blood or uncanny speed. It was his devotion.

He loved his mother fiercely. And Danaë, for all she had endured, raised him not as a prince, but as a good man. This did not go unnoticed.

The King of Seriphos, Polydectes, was a man who collected beauty the way pirates collected gold. He admired Danaë’s grace, Perseus’s strength—and he wanted one but feared the other.

He tried wooing Danaë with gifts and compliments, but she rebuffed him with polite disdain. She’d been seduced by a god; what hope did a sunburnt despot have?

Polydectes, insulted and humiliated, turned his attentions elsewhere—publicly.

“I shall marry the fair Hippodamia!” he announced to the court one evening, smug as a cat fat with lies. “But of course… a king needs wedding gifts.”

Every man in Seriphos was expected to bring a horse. A fine tradition, except for one detail: Perseus owned no horse. He and his mother had barely survived on fish and kindness. They had no gold, no land, and certainly no stable.

Polydectes knew this.

It was a trap, and everyone knew it except Perseus.

But instead of shame or excuses, the boy stood proud and said:

“I have no horse to give, my king… but if you would ask for a greater gift, name it, and I shall bring it.”

The room fell silent.

Polydectes smiled a smile that had no warmth in it.

“Then bring me the head of Medusa, the Gorgon.”

Gasps followed. Laughter. Then silence again. Even the guards shifted uncomfortably.

Everyone knew the tale. Three sisters, born before the gods themselves. Stheno—the strong. Euryale—the winged. And Medusa—the youngest and most beautiful, cursed by wrath. Snakes for hair. Eyes that turned men to stone. A death so swift it made beheading her seem generous.

Polydectes thought he had won. A boy against a legend? It would be a death sentence disguised as a quest.

But Perseus only nodded.

“Then I shall return with her head.”

Foolish? Perhaps. Brave? Absolutely. And somewhere, high on Olympus, Athena opened one eye with interest.

The game was on.

Act III: The Garden and the Gorgon

Medusa and her immortal sisters—Stheno and Euryale—were known as Gorgons: monsters, or so the world insisted. They were said to wear serpents for hair, bear fangs like beasts, wings of burnished gold, and eyes that turned the living to stone. Perseus knew none of this.

According to King Polydectes, they were just a nasty trio of snake-women who preyed on the weak. Nothing a good sword swing couldn’t fix.

Before setting out, Perseus did what any well-meaning (if dimly clever) demigod does: he made a sacrifice. A bull, to be specific. Most of it he ate—he was a growing boy with heroic metabolism—but the heart and bones were offered to Zeus, along with a heartfelt prayer for guidance.

Zeus, who hadn’t stopped caring for Danaë or the boy she'd raised with salt wind and grit, didn’t respond directly. But he did send word up Olympus:

“Any of my divine children want to help their little brother not die?”

Athena answered first. Purposeful, quiet, calculating. She had her reasons.

Hermes answered second. He thought it might be amusing—and besides, he liked the kid. Bit thick, but earnest.

Hermes appeared first, in a gust of wind and wit. He brought Perseus two things: his own winged sandals, and—less ethically—Hades’ Helm of Darkness, which Hermes had “borrowed.”

“Thievery,” he explained, “is just aggressive borrowing.”

Then came Athena, gleaming and grave. She gave Perseus her mirror-polished bronze shield.

“Do not meet her eyes,” she warned. “Let her reflection be your only truth.”

She also handed him a kibisis—a god-woven bag designed to contain the severed head of a still-cursed Gorgon.

“Even in death, her power will linger.”

Finally, she gave him a quest: seek the Graeae, the witches who knew where the Gorgons hid. Then find the Hesperides, guardians of the Herpe—a blade honed to sever divine flesh.

So, Perseus set out.

He found the Graeae first—three ancient, bird-like crones who shared a single magical eye and a dragon’s tooth between them. Sisters to the Gorgons, and even less polite.

They mocked him. They threatened him. They dismissed him entirely.

So Perseus did something clever (for once). He slipped on the helm, turned invisible, and spied on them until they passed the eye from one clawed hand to another. Then—snatch. Eye stolen.

They shrieked. He offered a trade: directions to Medusa’s lair in exchange for the return of their magical sight.

Grumbling curses older than language, they told him: the Gorgons lived on the Isle of Sarpedon, a crumbling ruin surrounded by cursed gardens, petrified sentinels, and silence.

He left them their eye. Eventually.

Next, he sought the Hesperides—twilight nymphs who danced on the edge of the world and kept apples of gold and secrets sharper than blades. They gave him the Herpe, a blade forged in starlight, curved like the crescent moon and bound in silver. Weapon in hand, Perseus flew for Sarpedon.

The cavern was quiet.

Statues lined the halls—men frozen mid-motion, faces contorted in awe, terror, or pride. A garden of stone. A graveyard of ego. And then, in the reflection of Athena’s shield, he saw her.

Medusa.

Not roaring. Not monstrous.

Just... still.

Beautiful, cursed, and still. Serpents coiled across her shoulders like sighs. Her eyes—veiled—still shimmered with ancient pain.

She did not run. She did not scream. She looked into the shield’s reflection and whispered:

“Athena sent you.”

And Perseus—heart pounding, sword shaking—raised the blade.

“Thank you,” she said.

And he struck.

There was no dramatic scream. Just silence, and then the soft hiss of severed snakes slumping to the floor.

He placed the head gently into the kibisis. Even unseen, her presence lingered—like storm lightning after the flash.

As he turned to leave, something in the cavern shimmered—an object, tucked among ancient relics and scattered bones. A bridle, braided from gold and leather, adorned with polished sea-stone. Magical, no question.

Perseus, ever the practical looter, pocketed it with a shrug.

“Never know when a fancy horse leash might come in handy.”

That, of course, was the moment the house woke up.

Stheno and Euryale had sensed the theft, and unlike Medusa, they were not in a forgiving mood.

They descended like shrieking tempests—claws flashing, wings tearing the air, voices raw with fury.

Perseus did what most demigods would in that moment: panicked and fled.

He sprinted through the corridors of statues, sandals flapping, blade rattling at his side. And as Stheno nearly caught his arm with a hooked talon, he remembered—

“Oh right. The helmet.”

He shoved it onto his head mid-flight—and vanished.

Invisible now, he slipped through shadows, evaded furious shrieks, and finally—mercifully—escaped.

He did not look back.

Act 3.5 – That One About Atlas? Yeah, No

Greek storytellers will swear that after escaping the Gorgon’s lair, Perseus flew west, encountered the Titan Atlas, and, in a moment of divine judgment, turned the great being into the Atlas Mountains with a single flash of Medusa’s gaze.

That didn’t happen.

What did happen was this:

Perseus got drunk in a taverna while waiting for the next boat back to Seriphos and, while showing off, may have embellished the truth a little.

Or a lot.

The tale spread—as tales do—and poor Atlas, who had absolutely nothing to do with anything, ended up immortalized in myth as a mountain range. A very impressive mountain range, sure, but not exactly a willing participant.

Perseus would later protest, “Hey, it was a joke!” But by then the bards had already written the song, the vase painters had done their thing, and Atlas was a landmark.

Meanwhile, having clearly forgotten he was wearing winged sandals, Hence the boat ride, Perseus finally took a closer look at the bridle he’d lifted from Medusa’s lair. It shimmered with divine craftsmanship—sea-stone beads, golden etchings, and something distinctly mythic in its aura.

He ran his fingers along its surface—and the sky split with a thunderclap.

From the clouds descended Pegasus—the winged horse of legend, pure as moonlight and fierce as a storm.

“…Huh,” said Perseus, blinking. "Neat"

He did not tame Pegasus. He accidentally summoned him. Using a relic he barely understood.

But those who saw him soaring across the skies—hair wild, hero's bag slung at his side, divine steed beneath him—assumed, quite naturally, that he had done something epic to earn it.

Which brings us to Bellerophon.

He actually did tame Pegasus.

Slayer of the Chimera. Rider of legends. Noble warrior of Corinth. Thrown from Olympus for daring too high.

And to this day, even in the Elysian Fields, Bellerophon sulks.

Muttering, “That little brat stole my thunder…”

Act IV – A Date with Destiny (and Andromeda)

After barely surviving two furious immortal Gorgons, fleeing with a magical horse, and not turning a Titan into a mountain, Perseus did what any self-respecting demigod would do with the freedom of the skies at his feet:

He took a boat.

Why? No one knows. Maybe he thought Pegasus needed a break. Maybe he got airsick after flying. Maybe he just didn’t think too hard about it—his usual method.

In any case, the journey back to Seriphos didn’t go as planned.

The Queen, the Boast, and the Bureaucracy

His detour led him south to the coast of Ethiopia—a kingdom not currently enjoying its time in the spotlight. The trouble began when Queen Cassiopeia, blessed with beauty and unburdened by humility, made a catastrophic boast:

“My daughter Andromeda is more far more beautiful than the Nereids. Smarter, more skilled and a better singer!”

Now, the Nereids—Poseidon’s extended aquatic family—were known for their vanity, viciousness, and willingness to escalate petty slights into full-blown divine vendettas.

They complained.

Poseidon, already irritable and knee-deep in sea monster paperwork, gave a weary sigh and unleashed Cetus—a draconic leviathan—to remind everyone what happened when you insult sea nymphs.

Cetus tore through the coast like a natural disaster with scales, coils and fangs.

Desperate for a solution (and maybe an opening to seize power), the local oracle Ammon declared: “Only the sacrifice of Andromeda will soothe the sea’s fury!”

Nobody questioned this. Naturally.

Well nobody but Andromeda did. She did rather loudly. But no one listened.

She was chained to a seaside cliff in ceremonial silk, surrounded by trembling priests and very few answers. A princess turned scapegoat.

Enter: The Hero on a flying Horse

Fate—or terrible navigation—brought Perseus to her just in time.

He saw her first, lashed to the rock, face proud despite the salt wind. His heart skipped a beat, then another, then possibly forgot how to beat at all. She was radiant. Also endangered.

Andromeda, for her part, saw a shirtless stranger gawking at her from a boat and briefly wondered if death might be less embarrassing.

Then Cetus rose from the waves, all teeth and roaring vengeance.

Perseus knew then and there that it was Hero time.

Perseus snapped out of it, fumbled for the magical bridle, remembered the sword and the sandals, and vaulted onto Pegasus. In a flash, he was airborne, cloak flapping dramatically behind him like a man who planned this all along.

He didn’t, never did, he didnt have plans so much as tiny fragments of actual plans that sounded awesome in his head.

The fight was brutal. Cetus was no idle monster; he was divine punishment with scales and scalding steam for breath. Perseus took a beating—ribs cracked, tunic torn, a truly humiliating splash—but eventually, with one final, screaming dive, he buried the Harpe blade in the beast’s neck.

Victory.

Later, when asked about his strategy, Perseus would admit:

“…Honestly? I forgot I had Medusa’s head. Otherwise I'd just have turned Cetus to stone in one go”

But again—he looked amazing, so it was fine.

Andromeda the Wise

Once rescued and draped in an apologetic cloak, Andromeda did what most princesses in myths don’t—she asked questions. They talked. She learned quickly that Perseus wasn’t the brightest star in the heavens—but he was brave, kind, and capable of great things when properly motivated (usually by danger, snacks, or her smile).

He, in turn, was smitten. Not just by her beauty, but her sharp wit, her command of language, her subtle sarcasm when dealing with absurdity. A brain and a backbone? He was doomed.

He proposed.

She accepted, in what may have been one the shortest love stories in the ancient world.

Her parents, thoroughly relieved, gave their blessing. Oracle Ammon vanished under mysterious circumstances shortly after.

No one investigated. No one wept.

A Wedding and a Dowry

The ceremony was lovely.

Until Phineus, Andromeda’s original (and useless) fiancé, crashed it.

He waved around scrolls, shouted about promises, and made vague threats.

Perseus reached for his sword.

On pure acident the kibisis opened. Medusa’s head gleamed.

Phineus stopped shouting.

He also stopped moving. Permanently. One might say he struck a statuesque pose.

Home Again

With no further delays, the couple mounted Pegasus (who was still only mildly annoyed at being involved in any of this) and soared back to Seriphos.

There, they found King Polydectes mid-harassment of Danaë.

Andromeda, unflinching, simply said: “It’s time to give him his Dowry dear husband.”

Perseus, with all the dignity a vengeful son can muster, opened the kibisis one final time.

Polydectes joined the stone gallery, still reaching for Danaë in his final pose—forever remembered as a man who reached too far.

Dictys was crowned king.

Danaë was safe.

Perseus and Andromeda, finally free of monsters, curses, and tyrants, looked to the horizon together.

(Except Bellerophon. He still wont shut up about Perseus. But that’s another story.)

Act V – Prophecy, Mushrooms, and the Founding of Things

Perseus, ever the respectful borrower (at least when gods were involved), returned the magical artifacts he’d been loaned.

Medusa’s head went to Athena, who placed it with reverence upon her aegis. In return, she allowed Perseus to keep the harpe sword and the magical bridle of Pegasus.

And seeing as he also had Andromeda by his side, all in all, it was what a hero might call a “net gain quest.”

He planned to live a quiet life as the noble adopted son of King Dictys. Maybe grow olives. Raise kids. Possibly stop accidentally stealing other heroes’ myths.

But fate, as ever, had other plans.

The Deadliest Frisbee in Greece

Acrisius, King of Argos—and Perseus’ dirtbag grandfather—had not forgotten the prophecy: He would be killed by his own grandson.

Upon hearing that Perseus had not only survived but flourished, Acrisius panicked. Like any cowardly tyrant with a cursed grandchild, he ran off to Larissa, reasoning that distance and plausible deniability could thwart destiny.

Destiny, unfortunately, had a flair for comedic timing.

Larissa was just about to host a major athletic festival, and Perseus—ever eager to flex his demigod muscles—entered the games with Andromeda cheering him on and Danaë clutching her heart every time he so much as touched a discus.

During a heated match of quoit (think: discus, but with more collateral damage), Perseus unleashed a particularly mighty throw.

Right at that moment, Acrisius—blissfully unaware—stepped into its path.

He died instantly.

The prophecy was fulfilled.

The crowd went silent.

And Perseus was left standing there with the discus in one hand and a look that said, “Oh no. Not again.”

It was, as the poets later wrote, "the most underwhelming death by prophecy of the century."

Crimes, Crowns, and Clever Wives

By blood, Perseus could now claim the throne of Argos.

Unfortunately, Greek law—especially the “accidental patricide-by-sport” clause—was quite clear. Ritual exile, purification, and a public apology to the gods were required, regardless of how well-meaning your lethal frisbee had been.

So, in a move that surprised no one but impressed everyone, Andromeda negotiated a clean solution:

Perseus would trade the throne of Argos to his friend, Prince Megapenthes, in exchange for the nearby kingdom of Tiryns.

Two royal headaches solved. One PR disaster averted.

And not a single pitchfork-wielding mob to be seen.

City-Builder, Snake-Slayer, Mushroom-Namer

From his new seat in Tiryns, Perseus—alongside Andromeda—entered his “urban planning phase.”

Together, they founded the city of Amandra, later called Ikonion, eventually known to the world as Iconium (modern-day Konya). They also established the mighty city of Mycenae, which Perseus—over Andromeda’s very vocal objections—named after a mushroom he had seen and thought looked neat.

Later in life, Perseus went full founder-mode:

Defeated the Isaurians and Cilicians, as one does.

Built the city of Tarsus, thanks to an oracle that told him, “Build where your foot touches the earth as you dismount your horse.” As one also does.

Allegedly conquered the Medes, renamed the land Persia, and taught the local magi about the Gorgon’s power.

And once, when a fireball fell from the sky (possibly a meteor, possibly Dionysus being dramatic), Perseus allegedly caught the sacred flame and gifted it to the people.

That last one is widely considered a drunken tavern story, but it has a lovely fresco in the royal archives, so who's complaining?

Epilogue – The Perseid Legacy

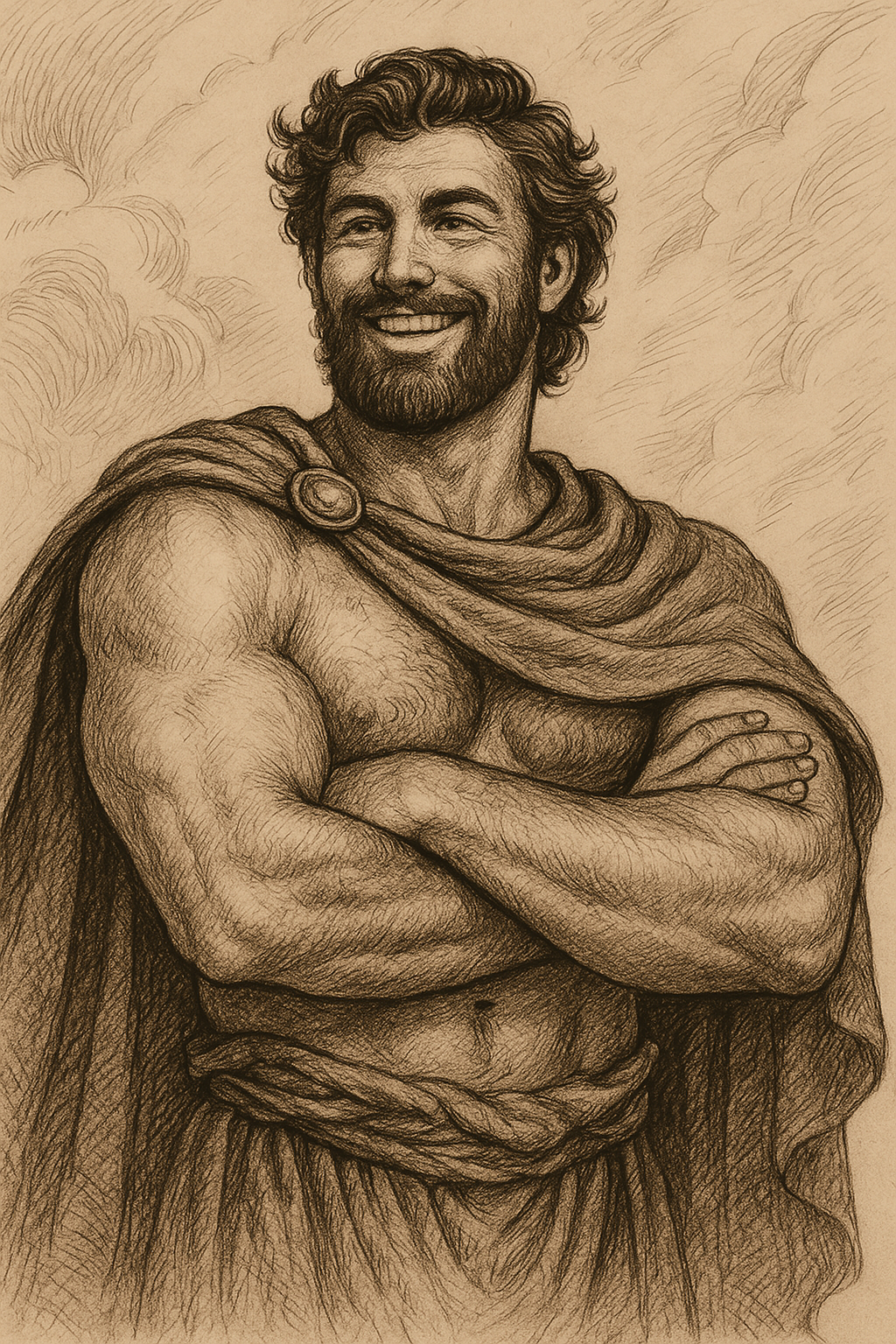

Whatever the scholars say, Perseus became a legend.

He stood beside Cadmus and Bellerophon (who, it yet again must be said, still hasn’t forgiven him for the Pegasus incident) as one of Greece’s greatest heroes.

He was the son of Zeus and Danaë, and through his line would come Heracles—making Perseus both his great grandfather and half-brother.

Which, in Greek mythological family trees, is honestly pretty tame.

He fought monsters, toppled tyrants, outwitted witches (eventually), and founded cities that would stand for centuries.

Children

Now I need to read the original myths :D