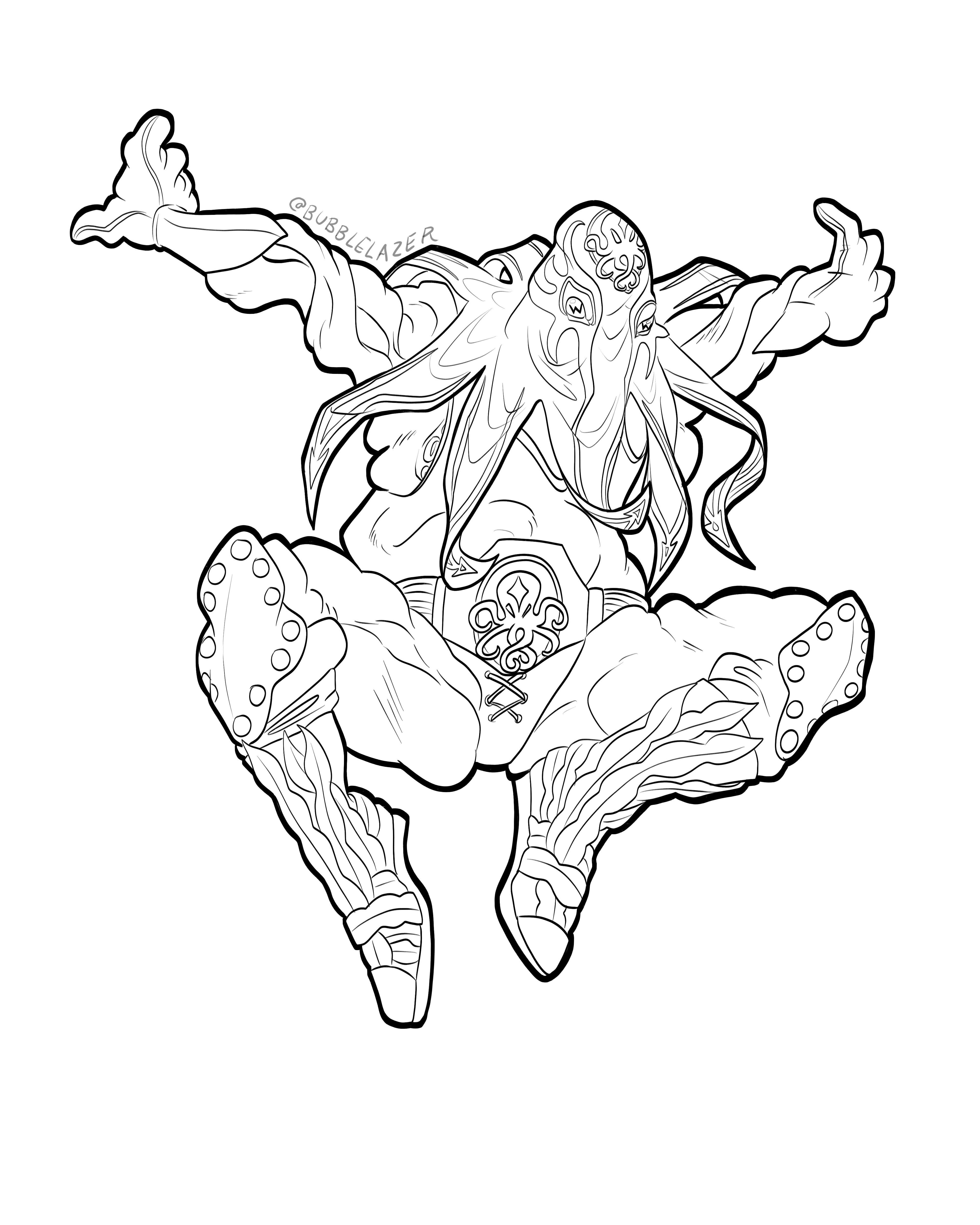

Mother Blackstone/Jet Black

Mother, Crone, High Priestess Casandra Evelyn Blackstone (a.k.a. Jet Black, The Velvet Matriarch, The Witching-Hour Madam, London’s Lady Witch, Gothic Bombshell of Bath, The Camp Queen of Midnight British TV, The Dark Temptress of Old Soho, The Crone of the Black Moon, “Witch Mommy” , Mummy B.)

Physical Description

General Physical Condition

Cassandra maintains excellent physical condition—part yoga, part witchcraft, part refusing to let age tame her. She’s flexible, strong, and moves with the smooth confidence of someone who knows exactly what her body can do and delights in doing it. Ask her how she stays in such good shape and she’ll just smile over her glasses and purr, “If you’re that interested, poppet… come have a closer look.”

Body Features

Cassandra describes her body with wicked, unapologetic delight: “curves for days, soft everywhere it counts, and larger than life.” She’s voluptuous, powerful, and radiates the kind of confident sensuality that only grows richer with age. Every inch of her feels intentional—lush hips, generous breasts, a waist that still knows how to tease an hourglass, and a presence that fills any room long before she speaks.

Facial Features

Cassandra carries the kind of beauty people call “classic” with a touch of posh British hauteur—high cheekbones, a sculpted jaw, and eyes sharp enough to cut silk. Even without makeup (which she treats as ritual, art, and armour in equal measure), she’s striking. There’s a natural refinement to her features: expressive brows, a wickedly knowing smile, and eyes that gleam with intelligence, mischief, and just a hint of witchfire.

Identifying Characteristics

Cassandra’s most infamous identifying feature is one she jokes about constantly: “my tits enter a room a full two seconds before I do.” She delivers the line with such practiced wickedness that it’s become part of her legend. Beyond her celebrated cleavage, she’s known for her raven-black hair, velvet voice, dramatic eyeliner, and the unmistakable aura of a woman who knows exactly who she is and enjoys every inch of it.

Physical quirks

Cassandra likes to insist, “Darling, everything about me is a quirk—I’m horror camp poured into a dress so low-cut it’s illegal in several countries.” Her physical mannerisms are as dramatic as her wardrobe: expressive hands, a hip sway meant to hypnotize, and a habit of striking poses even when she’s alone. She moves like someone who grew up on stages and in spellcircles—fluid, sensual, a little wicked, and always aware of the effect she has on a room.

Special abilities

Cassandra is a master of several magical arts—necromancy, modern eclectic witchcraft, traditional British Craft, and tantric magic—and she excels in all of them with unnerving grace. She’s both student and teacher, always hungry to learn and just as eager to pass on what she knows. Her natural affinity for magic runs deep: she senses energy the way musicians hear pitch, reading the ebb and flow of spellwork, spirits, desire, and death with effortless precision.

Anyone who dismisses her as “just a pretty face” very quickly learns why she’s known in magical circles as a witch queen—and why even seasoned practitioners treat her with a mix of awe, respect, and just a touch of fear.

Apparel & Accessories

Cassandra’s wardrobe is a love letter to the goth, punk, and rock-and-roll chaos of 1980s Britain—dark, wild, rebellious, and somehow still effortlessly elegant. She’ll happily tell you her greatest inspirations are Lily Munster and Morticia Addams, “with a dash of Velvet Hammer glamour.” Her clothing collection is enormous and gloriously eclectic: vintage lace, velvet gowns, leather jackets, corsets, fishnets, ripped skirts, and dresses with necklines so plunging they qualify as geological features.

When she’s working as Mother Blackstone, she favours black satin, dramatic silhouettes, and that unmistakable “goth queen” aesthetic—high glamour, high contrast, high cleavage.

Her accessories are just as expressive. Some days it’s a few subtle silver pieces; other days she jingles like an occult chandelier, stacked in rings, bangles, and necklaces etched with runes, sigils, pentacles, and old Celtic motifs. Nearly all of it is functional: spell foci, protective talismans, enchanted keepsakes, or bits of magic she likes to wear simply because they make her feel powerful and delicious.

Specialized Equipment

After nearly thirty years as a practicing witch—and with the income to indulge her tastes—Cassandra has amassed a formidable collection of magical equipment. Her enchanted jewelry doubles as both fashion and spellwork, while her personal arsenal includes wands, rods, staves, and a cauldron seasoned by decades of rituals. Her athame is a particular favourite: once a WWII British trench knife, now reborn as a consecrated blade that cuts through lies, bindings, and spirits with equal ease. Beyond these she keeps all the classic tools of the Craft—crystal grids, scrying mirrors, incense burners, altar bells, tarot decks, runic sets—each one carefully chosen, lovingly maintained, and used with the confidence of a witch who knows exactly what she’s doing.

Mental characteristics

Personal history

My name is Cassandra Evelyn Blackstone, but I was born with the far less interesting misfortune of being called Prudence Mary Clarges.

You may take a moment to wince. I certainly did, for the first sixteen years of my life.

I grew up in Bath, in a house that smelled of boiled vegetables, lavender polish, and repressed desire. My parents were the kind of painfully proper British Christians who considered “fun” a gateway drug to Hell. They never raised their voices, never raised a glass, and—I strongly suspect—never raised anything in the bedroom either. They slept in separate beds for “moral purity.”

They tried to raise a good, modest, quiet girl.

They got me.

Even as a child I wanted everything they disapproved of. I wanted to shout, to laugh too loudly, to chase boys and girls around the schoolyard, to sneak kisses behind hedgerows and see what all the fuss was about. I wanted to run wild instead of walking politely. Every time they said “That’s not proper behavior for a young lady,” something in me added it to a to-do list.

I might have grown up merely restless and naughty.

Then the ghosts arrived.

Well. One ghost, in particular.

And everything changed.

I was ten the day I woke up as a witch.

Not in the robe-and-wand sense you see on film—no smoky prophecy, no owl on the windowsill—just a rainy afternoon in Stacy Harding’s attic with a cardboard planchette and too much imagination.

My parents had forbidden “occult nonsense” in the house, of course. Which made it mandatory.

I cut the planchette myself out of cardboard, glued a chipped bit of glass into the center, and smuggled it to Stacy’s place along with my most dramatic scowl. Stacy, Lizzie, and I climbed up into the attic, shut the hatch, and lit a single candle like we’d seen in the films.

It was the perfect attic: dim, dusty, full of forgotten junk. Old dolls with cracked faces, trunks that smelled like dead winters, a rocking horse that squeaked when no one touched it. Stacy swore it was haunted by a wicked witch. Ten-year-old me found that idea insulting. If there was a witch here, I wanted her job.

We sat in a little triangle around a crate, fingers on the planchette, and I—ever the drama queen—asked the first question.

“Is there a witch here?”

Nothing happened.

You know that little sinking feeling when you’re a child and you think perhaps you’re not special at all, just silly? That.

Then the planchette moved.

Not the jittery jerk it does when the girl across from you is pushing it to scare everyone. No. Smooth. Certain. It shivered under our fingertips and began to slide.

Y.

O.

U.

And then—very slowly—it turned itself and pointed directly at me.

The air changed. Sharp and cold, like someone had opened a window into a winter from a hundred years ago. The candle flame leaned toward me. My skin prickled, not from fear, but from recognition.

Something inside me, ancient and wild and entirely female, opened its eyes.

I remember staring down at my own hand on that stupid bit of cardboard and thinking, without words: Oh. I see. It’s me.

I didn’t understand it.

I understood it completely.

There was magic in me. There always had been. That was the first moment I heard it answer back.

The thing in the attic, however, was not a witch at all.

The temperature dropped another degree. Stacy’s dolls tilted, just a fraction, like they were craning to watch. The shadows lengthened, and then he appeared: a pale, half-formed outline of a man in Victorian clothes, sketched like moonlight on fog.

He looked as startled to see us as we were to see him—soft eyes, sad mouth, gentle posture. Not a wicked spirit. Not a demon. Certainly not a witch.

A gentleman.

Stacy and Lizzie screamed, of course. Proper, piercing, respectable shrieks—echoing off the rafters, rattling the boxes. Lizzie bolted for the stairs, dragging Stacy with her, and in the chaos she kicked over a box of Christmas ornaments that cascaded after them like judgment.

I did not run.

I should have. I was ten. Everything I knew about ghosts said this was the part where they reached for you.

Instead, I just… looked at him.

My heart pounded, yes. My hands shook. But under the terror there was this deep, bone-level sense of finally. Like my whole life had been a radio just slightly off-tune, and suddenly the dial clicked into place.

He stared at me.

I stared back.

“Can you see me?” he asked.

His voice was low and cultured, with that lovely Victorian softness you only hear in old letters.

“Yes,” I whispered.

And there we were: a dead gentleman and a ten-year-old girl who had just discovered she was the witch in the attic.

His name was Algernon Davies. “Algie,” as I very quickly insisted.

He’d died in that house in the late 1800s, beaten by ruffians and left to bleed out in the attic when it belonged to someone else. In life he’d been a lover, not a fighter—a romantic, a man of poetry and impractical feelings.

Death had not changed that.

When his edges sharpened and he stood fully before me for the first time, he even tried to bow, remembered halfway through that he no longer had quite the right weight and momentum for it, and nearly drifted through a trunk. I giggled. He looked positively offended with himself.

“Are you a witch?” I asked him.

He hesitated, then smiled in that timid, hopeful way ghosts have when they’re not sure if you’re about to banish them.

“I am not, Miss…?”

“Prudence,” I said, with all the confidence of a girl who hasn’t yet realized what a curse of a name she’s carrying. “Prudence Mary Clarges. But I’d rather be a witch than a miss.”

His eyes softened.

“I believe, Miss Prudence,” he said gently, “that you already are.”

That was the first time anyone had named me correctly.

I walked home that evening with a ghost at my shoulder.

My parents, needless to say, would have had a collective aneurysm.

These are people who thought eyeliner was basically an invitation to Satan. If I’d come home and announced, “Mum, Dad, I’ve called up the wandering spirit of a murdered Victorian poet in Stacy’s attic and also I can move cardboard with my mind,” they’d have locked me in my room with a Bible and the vicar.

So I kept him secret.

Algernon was terribly good at being secret. He was always discreet, always hovering a little out of the corner of my eye when others were around. When we were alone, though, he’d sit on my bed or lean on my desk, hands folded behind his back, and talk.

He wasn’t a mentor, not like in the fantasy novels. More like a fussy, affectionate uncle with a tendency to quote poets at inopportune moments. But he believed me. He believed in me. And that was something I had never really had.

“You must be careful,” he’d say, watching me hover a candle flame with the single-minded intensity of a child who has discovered matches. “You are not wicked, my dear, but your parents’ world is very small. They will not see the difference.”

He taught me a great deal about humans, about hypocrisy, about love and loss and the oddness of death.

Magic, however, required more than a Victorian ghost with good manners.

I wanted spellcraft. Real spellcraft. I wanted the tricks and tools and rituals that would justify what I knew in my bones: that I was a witch, that I belonged to the old stories more than to Sunday school.

That meant books.

Finding magic in Bath in the late 70s was like hunting for sin in my parents’ pantry: it existed, but it was well hidden and never labelled honestly.

The local bookshops had “Occult” shelves—two miserable planks trying to look brave. Astrology cookbooks, cheap paperbacks about mystical Britain with glossy covers and no substance, herbal guides written by people who clearly thought dandelions were edgy.

My parents forbade even those.

“Witchcraft is devil worship,” my mother snapped once, snatching a folklore book from my hands and dropping it straight into the bin. “You are not filling your head with filth.”

So I did what any sensible girl would: I hid everything.

I copied things into notebooks and tucked them under loose floorboards. I drew sigils in the margins of my schoolwork disguised as doodles. I whispered questions to Algie in the flicker of candlelight and took notes on whatever answers he could give me—which were often more poetic than practical.

For three years, that was my education: scraps, stolen lore, and the loyal ghost of a murdered man.

Then, at thirteen, I found my people.

It was a Wednesday afternoon when I skipped study hall and wandered down toward Walcot Street instead. Fate smells like rain on old stone, if you’re curious.

Bath is very pretty, in that orderly Georgian way, but its back lanes are where the real city lives. Around Walcot there were secondhand shops, odd little galleries, cafés full of smoke and politics, and that simmering undercurrent of “we aren’t like the others” that always means you’re in the right place.

I found the shop in a narrow lane, tucked between a vintage clothing place and a café that reeked of clove cigarettes. The sign above the door was hand-painted, a heron perched beside a crown.

THE HERON & CROWN

Supplies for the Wise, the Curious, and the Lost

I saw that last word and felt personally called out.

Inside: heaven.

Shelves groaning under leather-bound grimoires and tatty old paperbacks. Jars of herbs and resins, each labelled in spidery script. Runes carved by hand. Candles in every shade from purest white to the kind of black that seemed to drink the light. Pendulums, tarot decks, charms in velvet-lined boxes. Incense thick enough to gag an archangel.

And people.

People in long skirts and velvet jackets, in denim and leather, with eyeliner heavier than my mother’s condemnation. Men with silver rings and women with shaved temples and tattoos, people who looked like they’d stepped out of an album cover and into a coven.

People who looked like me.

I must have been staring with open hunger, because one of them drifted over: a young witch with bare feet, curly hair, and arms full of ink. They smelled faintly of patchouli and good trouble.

“You’ve got the look of someone who’s already touched the other side, love,” they said. “Want some help finding your path?”

It was the first time anyone had ever spoken to me like that—not as a problem to be solved, but as something already true.

I nodded. Probably too quickly.

That was how I met Rowan, my first living magical teacher.

From there, the world cracked open.

I started spending my afternoons and evenings with the people around the Heron & Crown. I told my parents I was at “study club.” Technically, I wasn’t lying. I was just studying spellcraft instead of maths.

They taught me old British witchcraft: charms with threads and knots, hedgecrossing lore, ancestor veneration. They handed me stories of cunning folk who used to work quietly in villages long before anyone put pentacles on book covers.

I learned about ley lines and sacred springs, about how water remembers what you whisper into it. I learned grounding, proper casting and closing of circles, the basics of divination.

They also taught ethics—real ethics, not the brittle “thou shalt nots” I’d grown up with. The responsibility of magic. Consent. Consequences. Where you can bend things and where you absolutely should not.

Every lesson was a revelation: not just in magic, but in the truth that there was an entire culture out there in which I wasn’t wrong. I was expected.

“Magic isn’t sin, Pru,” Rowan told me, during one of our first serious conversations. “It’s a birthright. You’re not dabbling in something foreign. You’re remembering something you already know.”

Algernon watched all this with paternal pride. He’d flicker into being in the corner of a room above the shop and listen to discussions of ritual structure and energy flow like a man at the theatre.

“You remind me of the suffragettes,” he said once, fondly. “Determined, fierce, and unwilling to stay where society insists you belong.”

At thirteen I had one foot in my parents’ grey, suffocating world and one foot planted firmly in candlelight and incense smoke.

And then puberty hit.

And that was… spectacular.

Puberty is rarely dignified. In my case it made a point of being theatrical.

Over one summer my body decided to go from “spindly schoolgirl” to “forbidden painting in a Victorian gentleman’s study.” My waist cinched in, my hips and backside filled out, my face sharpened into something striking instead of merely cute.

And my breasts… well.

“I went to bed a broomstick and woke up a centre-fold,” I’ve told audiences for years. “Like some goddess had mis-clicked when distributing assets.”

My parents did not find this amusing.

They’d planned on a daughter who would remain safely dull until they handed her off to some nice, equally dull young man at thirty. Instead they got a dark-haired beauty with curves you could hang laundry on and a developing habit of walking like she knew it.

Their response was immediate and quintessentially British: longer skirts, higher collars, tighter rules. Lectures about temptation. Makeup forbidden. Jewelry monitored. Friends questioned. New church groups suggested with all the desperate cheer of people handing out cult pamphlets.

It didn’t work.

I saw the way boys looked at me. I saw the way girls looked at me—curious, shy, a little dazzled. I saw something in the mirror that was not a curse, no matter what my mother muttered about “modesty.”

It was mine. My body, my beauty, my power.

And I liked it.

The first person I asked for an impartial opinion was—of course—my ghost.

“Do I look… different?” I asked one evening, sitting at my little vanity. I’d just experimented with eyeliner for the first time, and I wasn’t sure if I looked sultry or like I’d lost a fight with a calligraphy set.

Algernon manifested beside the mirror, straightened his ghostly waistcoat, and gave me a once-over with admirable restraint.

“My dear Prudence,” he said finally, with grave sincerity, “you are blessed with a figure that a man of artistic leaning might call Rubenesque. And I assure you, that is meant as the highest of compliments.”

I laughed so hard I nearly fell off the chair.

But under the laughter, something shifted: pride, yes, and also awareness. My magic had always lived in my bones and breath; now I could feel it flooding my skin. Desire—my own and other people’s—became something I could sense, like warmth from a fire.

Puberty wasn’t just a physical bloom. It was a magical ignition.

My parents were terrified.

I was delighted.

By fifteen, my life was essentially two parallel universes pressed together.

In one: the Clarges household. Church, chores, a bedroom that might as well have been a prison cell. Constant battles over my clothes, my music, my friends, my notebooks, my tarot deck. They ransacked my room periodically looking for signs of “corruption” and always found something, because I kept very poor evidence-management but excellent hexes for discouraging nosiness.

In the other: Bath’s hidden magical community.

Pagans and cunning folk. Elderly herbalists who remembered things that weren’t in any book. Occult scholars with long coffee-stained fingers. Hedge witches. Queer mystics. Goths who loudly proclaimed they “didn’t believe in any of that” while carrying protection charms in their boots.

I had a coven by then. A proper, structured one. Our leader was Lady Anne Sorrel—a woman in her fifties with steel-grey hair, perfect lipstick, and a presence so commanding she could silence a room with a raised eyebrow.

She took one look at me the night Rowan brought me to my first formal circle and said, “Ah. This one will outgrow all her tutors.”

I glowed for a week.

At home, though, everything grew more volatile. My parents honed their disapproval into something almost artful. The more I showed up in black skirts and silver pendants, the more they tightened the screws. No youth group? Grounded. Talking back? Bible verses weaponized like little knives. I stopped trying to argue theology with them. I had no interest in fighting over who God did or did not hate.

Then came the kiss.

And the fury.

I was sixteen when my parents walked in on me kissing Stacy Harding.

It wasn’t sordid. It wasn’t some orgiastic scene from their nightmares. We were on my bed, fully clothed, soft and awkward and breathless. Two teenage girls fumbling their way through curiosity and affection the way teenagers have always done.

They opened the door without knocking.

We shot apart like guilty clichés. My mother dropped the laundry basket. My father went a colour I’d only ever seen on tinned ham.

Silence.

Then hell.

They shouted. They cried. They invoked Scripture like it was a baseball bat. The words they hurled at us were all the usual suspects: shameful, unnatural, sinful, perverse, wrong. They tried to blame Stacy. They tried to blame “those goths.” They tried to blame anything except the simple truth that their daughter loved more broadly than their doctrine allowed.

Stacy fled in tears. My mother threatened to call her parents. My father talked about “therapy” with the same tone he used for “exorcism.”

I stood there, shaking, listening.

And for the first time in my life, something in me refused to bend.

Not fear—anger.

How dare you, that new voice in my chest whispered. How dare you turn love into a sin and then call it righteousness.

I didn’t scream it. I wish I had. I just stood there and let their words splinter against me like stones against a wall that had finally decided to be a wall.

When they were done—spent, tearful, righteous—I went upstairs, slammed my bedroom door, and sat on the bed, fists clenched, shaking.

Algie appeared on the end of the mattress like a summoned thought.

He didn’t gasp or stammer or look appalled. He just folded his hands and said mildly, “You know, Miss Prudence, Mister Wilde fancied men. An extraordinary writer, even if a touch eccentric in his proclivities.”

I snorted into my pillow.

He went on, warming to his point. “People who favour love of their own manner,” he said, “have existed since the days of Homer. You are not wrong. You are simply human.”

That made me laugh and sob at the same time.

By the time I’d cried myself hoarse, I knew something with a new, diamond clarity: my parents’ world was not mine. It never had been. I’d been visiting under duress.

If they couldn’t make room in their hearts for who I was, then their hearts were too small. That was no longer my fault.

Later that year, during a particularly frigid dinner, they made their own declaration in clipped, reasonable tones: when I turned eighteen, their “legal obligations” ended. At that point, they would “have to consider” whether it was best for everyone if I left.

They said it like they were discussing the weather.

To another girl, that might have been devastating.

To me?

It was freedom with a side of spite.

They had just told me that the prison sentence had an end date.

I started counting days.

Once I stopped pretending I might someday fit their mold, things got easier in a strange way. I didn’t waste energy trying to win their approval. I put it into the life I was quietly building elsewhere.

I dove headfirst into the goth scene.

Bath in the early 80s thrummed at the edges with darkwave, post-punk, all the good deliciously miserable music. I went to cramped clubs and dingy basements, where speakers rattled with Siouxsie and The Cure and Bauhaus. Where the dance floor was a sea of black lace and leather and rejected children of polite society, all moving like we’d been born in the same storm.

I stitched my own clothes from charity-shop finds, velvet and lace and mesh cobbled into outfits that made adults murmur and teenagers stare with worship. I stayed out too late. I drank too much cheap cider. I kissed boys, kissed girls, kissed whoever made my heartbeat sound like drum machines.

Life—real life—finally tasted sweet.

At school I joined the drama club and walked onto a stage for the first time. That was another awakening. The theatre gave me something witchcraft and goth clubs didn’t: public transformation. I could be anyone. I could be a queen or a whore or a saint or a monster, and the audience would eat it up.

My secret fantasy solidified around then: horror films.

Hammer Horror, especially. Those brilliant, blood-red melodramas full of women like me: wicked and beautiful and doomed. I devoured them. Memorized lines. Studied the actresses—how they moved, how they held their mouths, how they balanced terror and seduction like two candles in one hand.

I wanted to be one of them.

I wanted to die screaming in a nightgown on screen for a living.

You know. As one does.

Seventeen came. My parents grew, if possible, even chillier. I, in turn, grew even less inclined to care.

I had everything that mattered: my friends, my coven, my mentors, magic, lovers, late-night music, secrets whispered in graveyards, circles cast under the moon.

In short: I had a life.

So when eighteen finally rolled around, I did not wait for them to march me out.

I packed my things—the books, the clothes, the talismans hidden in drawers. I took my notebooks, my tarot, my half-finished sigils. I slipped Algie’s old pocket watch into my coat pocket; it had long since stopped keeping mortal time, but it kept him close.

I walked downstairs and announced, calmly, over breakfast, that I was moving out.

My mother cried. My father went tight around the eyes. They said things about “choices” and “consequences” and “how hard life is without God.”

I thanked them for the roof and the food, for what little kindness had existed between us.

And then, before they could gather themselves to disown me, I disowned them.

“I am not yours to be ashamed of,” I told them. “I never was.”

Then I left.

I remember the sky that morning: pale Bath grey, still half-asleep. I stepped out of their house carrying a suitcase in one hand and a spellbook in the other.

On the pavement I stopped, closed my eyes, and took a breath.

“Cassandra Blackstone,” I whispered.

It felt right in my mouth. Delicious, even. Sensual, dangerous, theatrical.

I said it again.

I liked the woman who answered.

Prudence Mary Clarges died very gently that morning, without fanfare or funeral. I did not mourn her. I took her experiences, her pains, her joys, and folded them into my new name like herbs into a spell.

And just like that, I became myself.

London was exactly as unforgiving as everyone promised and twice as intoxicating.

By twenty-one, I was living in a one-room flat that might technically have been a glorified cupboard. The wallpaper peeled. The pipes groaned. The neighbours fought loudly and had even louder sex. I loved it.

By day—and often by night—I was a witch-for-hire.

Nothing glamorous. No epic duels on Westminster Bridge. Think less “Chosen One” and more “supernatural plumber.”

I read fortunes for nervous girls in Camden. Cleansed flats of cranky spirits who just wanted the stereo turned down after midnight. Mediated between ghosts and landlords. Brewed charm sachets for goths who wanted their crush to notice them. Did a great deal of work involving old houses, family curses, and people who’d inherited both in poor condition.

Magic paid poorly. The ghosts paid not at all.

My meals rotated between instant rice, tinned soup, and whatever vegetables were cheapest. I drank too much tea with far too much sugar. My flat was a hazard zone of secondhand furniture and tottering towers of occult books.

The coven back in Bath had promised I’d always have a spare bed there, rent-free. I loved them dearly for it.

I refused.

“I carry my own weight, poppet,” I told Rowan over the phone. “Even if it cripples me.”

Algernon became indispensable in that era. For a self-proclaimed “lover, not a fighter,” he had a real talent for handling the dead.

“I assure you, Miss Cassandra,” he’d say primly before drifting through a wall to shout at some belligerent spectre, “incorporeality has its strategic advantages.”

He’d return looking thoroughly pleased with himself, muttering about “young ghosts these days” with all the crotchety energy of a pensioner.

We muddled through.

Then the call came.

The call that changed everything.

My agent—yes, I had one by then, through a circuitous path involving open casting calls and a very patient drama teacher—rang my flat.

“They want you in Bristol,” she said. “Horror picture. Low-budget, but it’s a proper shoot. You’ve got a callback.”

“A callback,” I repeated, dumb with delight.

The film was called The Return of the Ripper. It had a script so thin you could see daylight through it and a budget that looked like petty cash.

My role?

“Topless Cultist #3.”

You might think that would bother me.

Reader, it did not.

A foot in the door is a foot in the door. I packed a bag, kissed Algie on the cheek (technically an air-kiss; ectoplasm is tricky), and took the train.

The director was very serious about the “topless” part.

“You’re comfortable?” he asked, trying not to look directly at my chest.

I looked him in the eye, unhooked my bra, lifted my shirt, and said, “When do we start?”

I got the part.

I also got a very memorable fling with a Scottish stuntman whose hands deserved their own agent and whose accent made even my Victorian ghost blush and excuse himself politely from the room.

No, it wasn’t love. It wasn’t meant to be. It was fun and warm and exactly the sort of experience I’d been denied as a teenager. Another brick in the foundation of who I was becoming.

The film itself was… trash. Glorious trash. Buckets of fake blood, dodgy lighting, sound design that deserved an apology.

But it did something important: it put my breasts—and the rest of me—in front of cameras.

The horror world noticed.

I discovered something about myself during those long days on set: I liked being seen.

On some level I’d known it for years. The theatre, the clubs, the way I savoured glances on the street. But film intensified it. The camera loved me, and I loved it back. The lens became a kind of altar, the lights a ritual.

Some actresses hate the grind of low-budget horror—the constant minor nudity, the screaming, the cold night shoots in lakes that weren’t heated nearly enough.

I thrived.

I liked being “the busty girl in the lake scene.” I liked the way horror fans remembered me even when I had no lines and died four minutes in. I liked that directors started saying, “Get that goth bird from Ripper for this.”

“Most of my early roles were topless,” I like to say on my show. “I was the extra who put the tit in title feature film, darling.”

I say it with pride.

My body had been a battleground in my parents’ house. On set, it was mine. My choice. My work. My pleasure.

The first proper milestone came with a scrappy little slasher titled Nightmare on the Moors. I got a name that time: Stacy Stalone, promiscuous teen, dead in the first act after delightfully irresponsible sex in a barn.

The script? Abysmal.

Me? Fantastic.

Reviewers hated the film. Some of them, grudgingly, admitted they liked me—my energy, my presence. Ten minutes of screen time, one absolutely ridiculous death, and a credit where my name was misspelled as “Cassandra Blackrock.”

I kept the poster anyway.

It still hangs in my home office.

That was the moment I knew: I wasn’t just dabbling. I belonged in horror. I belonged on screens.

The witch, the exhibitionist, the performer—they all shook hands and agreed they’d like to do this forever.

And then, just as I was settling into being a minor cult topless icon, magic reared its third head.

Tantra.

I did not learn tantric magic from a dusty old book or some robe-wearing guru.

I learned it from a woman named Shinu.

She was from Mumbai, with soft eyes and a wicked smile, and she turned up in my life like a gift from whichever goddess oversees curious disasters. We met at a house party after a shoot—too much smoke, not enough oxygen, the usual—and wound up talking in a kitchen for three hours about mythology and body memory and why Britain is so terrified of pleasure.

We fell into bed soon after.

One night, lying tangled in my sheets, she traced a symbol on my stomach with one fingertip—a slow, spiralling thing that made my skin buzz like a live wire.

“You feel energy differently,” she murmured. “You’re a prodigy. You move it without realizing you’re doing it.”

I told her I’d always been… aware. Of touch, of breath, of how desire sits in the air between people like static. She smiled like a woman who’s just found a favourite toy.

“Then you should learn to use it,” she said.

So she taught me.

Not just sex, though there was plenty of that. Breathwork. Focus. How to let sensation move through the whole body instead of trapping it in little guilty corners. How to weave intention into intimacy, into touch, into each exhale.

For me, tantra wasn’t some solemn ritual. It was an expansion of things I already knew: that magic lives in the body, that pleasure is power, that shame is a leash you do not have to wear.

Other witches noticed.

It’s one thing to be skilled at hedgecraft and spirit work. It’s another to be talented in three disciplines: practical witchcraft, necromancy by way of a resident Victorian, and tantra.

I was becoming something rare. Dangerous. Holy, in a way my parents would have burned me for.

Across the globe, the so-called Bronze Age of superheroes was dawning—old clean-cut capes fading, stranger and sexier figures emerging in their place.

I had no idea I was about to become one of them.

My first act of accidental heroism happened on a film set, fittingly enough.

We were shooting The Lighthouse Keeper, a gloriously camp adaptation of an old Torn Spandex pulp. I’d been cast as a minor villainess: Lady Darkwave. Sequins, cleavage, slit skirt, wig with more volume than the script, and a cape so dramatic it deserved its own dressing room.

I adored her.

One afternoon we were filming on location when a pack of local yobs wandered in—loud, drunk, and deeply unimpressed with film people taking up “their” space. They shoved crew, catcalled extras, kicked over equipment. One of them pulled a knife.

Now, there are rules in the magical world about hexing civilians in public. Rules I had technically signed off on.

I ignored them.

I muttered a sharp little curse under my breath, snapped my fingers, and sent every ounce of bad luck I could muster straight into the path of the knife-waving moron.

He took a step toward one of the PAs, caught his suddenly untied shoelaces, and went down like a felled tree into a pile of props. The knife skittered away. He howled. His friends laughed.

Then I stepped forward, still in full Lady Darkwave regalia, cape billowing as the wind machines whirred.

I raised my arms. I let my voice drop into that rich, purring register I use for monologues and seductions, and I began to chant.

Total nonsense, mind you. Dramatic Latin-ish syllables, a few scraps of the old tongue, the names of three demons who owed me favours, and my shopping list.

Didn’t matter.

Everyone on set knew it was real.

The air went cold.

“Algernon,” I murmured.

He manifested perfectly on cue: a coil of icy mist, chains rattling ominously, eyes glowing just enough to show through on film if anyone had been rolling.

“If I’m going to haunt, I shall do it properly or not at all,” he’d said beforehand, and he meant it.

The thugs bolted.

We were left in stunned silence, the director slack-jawed, the lighting guy crossing himself.

In that moment, standing on fake rocks in a fake storm in a costume built for male gaze, having just legitimately saved a bunch of people with real magic, I felt… incandescent.

I liked this.

I liked helping.

I liked being terrifying and glamorous at the same time.

I liked doing it in a ridiculous costume.

That was the night Jet Black was born.

I had access to wardrobe departments, prop houses, special-effects contacts. I also had exactly zero shame and a flair for tailoring.

I cobbled her together from the best bits: a bodysuit that hugged every curve like a lover, boots made for stomping and seducing, a domino mask to keep the mundanes from putting two and two together, a wig with gravity-defying raven curls, and a cape stitched with protective sigils on the inside.

Jet Black.

London’s witch of the night.

I stood in front of the mirror in my little flat, turned this way and that, and purred to my reflection, “Hope you’re ready for me, London. Tonight, Jet Black is on the prowl.”

Algie floated in the corner, looking like a proud valet.

“You do cut a striking figure, my dear,” he said.

That was the beginning.

I started small—street-level problems. Thugs, supernatural nasties, the usual. Protecting sex workers from both human and inhuman predators. Clearing alleyway spirits that had gone feral. Banishing boggarts from under bridges and hexing abusive boyfriends with impotence curses.

Jet Black became a rumour, then a news item, then a tabloid obsession.

“The Sexy Witch Vigilante,” they called me.

I adored it.

My magic sharpened with use. My presence became iconic: curves, claws, cape. I was part urban legend, part centerfold, part genuine protector of the night.

Of course, all this cost money. Costumes, charms, rent, film auditions. The horror roles helped, but they weren’t consistent.

I needed something… steady. Flexible. Glamorous.

And then my agent rang again.

“Stable, flexible,” she said. “You’ll love it. You’re made for it.”

I narrowed my eyes. “What’s the catch?”

“Late-night horror hostess gig,” she said. “You dress up, make jokes, introduce the films. They want boobs, banter, and a bit of witchy flavour. You, basically.”

I didn’t even pretend to hesitate.

Sign me up.

The show didn’t have a name when I first walked onto that empty little studio set. Just a concept: monster movies, midnights, a sexy host to keep lonely insomniacs company.

The director was there waiting: Roland Thorne. Handsome, droll, the sort of man who looked like he’d been poured into his suit and seasoned with mischief.

“Got any ideas?” he asked, leaning on the arm of a battered chair that would soon become my chair.

“Loads,” I said. Confidence is half the magic.

“Let’s hear ’em, luv.”

So I took a breath and pitched myself.

“Mother Blackstone,” I said. “I’m a witch. Proper witch. Campy, sexy, all curves and candles. I make lewd jokes, horror trivia, breast jokes especially. I flirt with the audience, flirt with the monsters, flirt with the cameraman. We give them horror and horniness in equal measure.”

He stared at my chest for a moment—professionally, I’m sure—then looked up and said, in a tone of pure sincerity:

“Love… they’re nothing to joke about.”

Reader, I married him.

Not immediately. But I decided, in that instant, that I was going to.

He gave me free rein. The persona settled on me like a familiar cloak: Mother Blackstone, London’s lady witch of the telly, camp queen of the witching hour. I strutted across sets in corsets and velvet, cackled at bad special effects, teased viewers with innuendo so thick you could spread it on toast.

It worked.

Massively.

Mother Blackstone became a cult icon. Horror fans tuned in for the movies and stayed for me. Teenagers across Britain, up too late with the volume down low, discovered both cleavage and cryptids in the same breath.

I became:

A goth beauty symbol.

A walking encyclopedia of horror lore.

A sex-positive agony aunt.

A witch on their screens who actually knew what she was talking about.

And all the while, jet-black capes still flapped in the London night.

Jet Black didn’t retire when Mother Blackstone arrived. I just got busier. Filming in the evenings, rooftops after. Reading emails from fans at dawn with bruised knuckles and lipstick half-smeared.

Somewhere in there, Roland and I stopped pretending we weren’t hopelessly into each other.

We handfasted in a small pagan ceremony—candles, ivy, friends, coven, and one very teary Victorian ghost hovering like a proud uncle. Later we did the legal bits for the government, but the real wedding was in the circle.

Then Esme came along.

My miracle.

Esme Thorne-Blackstone arrived as if someone had asked the universe, “What if we made a child out of Cassandra’s fire and Roland’s heart?”

She had his eyes, my hair, and a laugh that sounded like someone had lit a candle in the middle of a storm.

From the moment she could focus those baby blues, she could see Algie. He spent her toddler years in a state of gentle panic, alternately trying to keep her from running through him and from stealing his pocket watch.

I have never been happier than I was in those years: wife, mother, witch, horror hostess, vigilante. It was chaotic and exhausting and sometimes I’d come home from a night shoot, peel off the Jet Black costume, nurse a baby, and fall asleep smelling of fake blood and baby shampoo.

I loved it.

Then Roland got sick.

Slowly, at first. A cough that wouldn’t go away. Fatigue. Doctors. Tests. Words like “aggressive” and “advanced” and “inoperable.”

I threw everything I had at it: healing circles, herbal protocols, bargains with spirits, quiet weeping prayers to gods I don’t even like. Magic slowed it. Nothing stopped it.

In the end, there was only us. His hand in mine, Esme asleep at home, Algie standing in the corner of the hospital room looking more solid than I’d ever seen him.

“Your pain is over, my love,” I whispered as Roland’s breath grew thin. “Sleep now… until you and I can dance beneath the moon again.”

He squeezed my hand once.

Then he was gone.

Esme was ten.

I knew immediately what had to happen.

Not because anyone demanded it, not because the city issued some ultimatum, but because love did.

Jet Black had always been a joy and a release and a kind of service. But she was also risk. Late nights, fights, hazards I could no longer justify with a child who’d already lost one parent.

So I hung up the mask.

I folded the bodysuit away. I stored the boots. I kissed the cape and hung it carefully in the back of the closet.

Jet Black retired.

Mother Blackstone did not.

That persona—the witch, the hostess, the velvet-voiced flirt of the witching hour—was something Roland and I had built together. It was ours. Keeping her alive on screen, in podcasts, in books, in public appearances—that was keeping him alive, too.

So I poured myself into it.

The Witching Hour grew into more than a tv slot. It became a podcast, then a media web: horror analyses, occult education, sex-positive advice, spiritual guidance for weirdos and witches, all delivered in my best late-night purr.

People listened.

They wrote in about magic, about desire, about grief. I held their hands through earbuds and told them the things I’d needed to hear at sixteen: you are not wrong, you are simply human. Your body is not your enemy. Your weirdness is not a flaw.

Between appearances, lectures, books, merch, my frankly scandalous calendar one year, and a few good investment choices, Esme and I were secure.

She grew into herself: brilliant, sharp, studying at university, calling me to complain about exams and to ask for recipes. Roland’s curiosity, my fire.

The house grew quiet.

Algie and I kept each other company. I did yoga, wrote, worked, flirted with interviewers half my age, occasionally dated, occasionally didn’t.

Life was good.

But magic never truly sleeps.

It started as an itch.

An old one. The kind you get in your knees when you haven’t danced in a while. In my case, in my hands when I hadn’t hexed a mugger in months.

One night, the house was too silent. Esme was away at uni. My inbox was under control. The latest episode was recorded and scheduled. The wards were humming quietly. There was no crisis, no emergency.

Just… stillness.

I made tea. Wandered a bit. The house felt too big, the way houses do when the children grow up.

Somehow my feet took me to the spare room I never quite called what it was: the costume room. I opened the closet.

There it all was, waiting.

The bodysuit. The boots. The wig, still glossy. The domino mask. And the cape, sigils stitched on the inside, swaying just a little as if some passing breeze had kissed it.

My breath caught.

“I’m too old for this sort of thing,” I muttered.

Even I didn’t believe me.

I am a master witch, fit from years of yoga and certain athletic horizontal activities. Stronger now than I was at twenty, in many ways. My magic is tempered, honed. My confidence is no longer a reaction to someone else’s shame; it’s a simple fact.

I am not diminished by age.

I am sharpened by it.

A familiar chill brushed my shoulder.

Algernon appeared, as he always does when I’m about to make a questionable decision.

“You always did enjoy being London’s lady witch,” he said quietly.

“You’re not helping, Algie,” I sighed.

But I was smiling. Wickedly. The way you smile when you remember an old lover and consider dialing their number.

I touched the mask with my fingertips. The leather was cool and familiar.

Maybe I was too old.

Maybe I wasn’t.

Maybe “too old” is just something bitter people say when they want you to join them in surrender.

I am a witch. We do not retire. We evolve: Maiden, Mother, Crone.

The Crone is not a withered cliché. She is the final, most powerful stage. The woman who has walked through fire, buried her dead, raised her children, survived her heartbreaks, and come out the other side with laugh lines and scars and absolutely no patience left for nonsense.

I looked at that cape and thought: why shouldn’t the Crone fly?

I slipped the mask up against my face and whispered, “Jet Black… are you ready to prowl again?”

And somewhere, deep in my chest where the first spark had woken at Stacy’s attic planchette, something answered.

Yes.

Gender Identity

Cassandra identifies unapologetically as a woman and a witch, devoted to what she calls the “dark divine feminine”—the wild, sensual, shadowed face of goddess-energy that lives in blood, lust, grief, and laughter at 3AM. She delights in that archetype and chooses to embody it in her magic, her art, and her body, but she’s adamant that it’s her path, not a template. Gender, to her, is a living spell each soul writes for themself: she honours all expressions of it, fiercely supports trans and non-binary folk, and has never believed anyone is obligated to mirror her devotion to the dark goddess just because she wears it so loudly.

Sexuality

Cassandra is proudly bisexual and gloriously sex-positive. For her, desire is sacred—a form of magic, a source of joy, a place where bodies become honest and the soul gets to laugh. She doesn’t compartmentalize orientation into tidy boxes; she loves who she loves, craves who she craves, and celebrates the full spectrum of human beauty with equal reverence. As a Witch, she treats sexuality as a natural, holy expression of life-force, never as something to hide or sanitize. Sex is pleasure, connection, ritual, comedy, comfort… one of her favorite delights in a world far too short for shame.

Education

Cassandra completed a standard high school education, though she poured most of her academic passion into drama, theatre performance, and anything that let her step onto a stage. Her real education grew in two unexpected directions: first, in the deep well of magical lore she absorbed through covens, mentors, spirits, and decades of hands-on practice; and second, in the fiercely practical skills of a self-made businesswoman. Building The Witching Hour and the Mother Blackstone persona into a thriving brand taught her marketing, media management, publishing, public relations, and the subtle art of turning charm into income. Her schooling may have been ordinary—her education was anything but.

Employment

Cassandra’s employment history is a glorious mess of survival jobs, magical side-gigs, and chaotic glamour. She slogged through miserable sales positions, hustled as a witch-for-hire fixing supernatural problems for pocket change, then stumbled into the world of low-budget horror as a busty extra and, eventually, a beloved B-movie scream queen. All of that was just the prelude. She truly found her calling as the horror hostess of The Witching Hour—a job she adores because it isn’t really a job at all. On camera she isn’t playing a character so much as being her unfiltered, velvety, wicked self… and finally getting paid properly for it.

Accomplishments & Achievements

Cassandra’s life is an almost ridiculous stack of accomplishments: she’s been a vigilante witch-hero prowling London rooftops, a cult-favorite horror actress, a late-night sex symbol, and is now widely respected as one of the UK’s most formidable Crones—a magical matriarch whose wisdom is sought by witches, academics, and fans alike. Yet if you asked her what achievement she’s proudest of, she wouldn’t mention the costumes, the magic, or the fame. She would say, without hesitation, that the greatest thing she has ever done is raise her daughter, Esme.

Failures & Embarrassments

Cassandra likes to say she is “immune to embarrassment”—and it’s mostly true. She’s tripped on stages, flubbed spells, botched auditions, chased the wrong lovers, and once accidentally hexed a cameraman’s trousers clean off… but none of it lingers. She treats failure the way she treats spilled wine: wipe it up, laugh about it, pour another glass, move on. Her mistakes never fester or weigh her down; she simply refuses to let any setback sit on her thoughts “like a fat toad.” Life is too short, magic too wild, and pleasure too plentiful to waste time on shame.

Mental Trauma

Cassandra considers herself remarkably healthy—emotionally, mentally, magically. Her parents almost broke her, pressing shame and rigidity into her childhood like iron bars, but she slipped through them before they could cage her spirit. She carries scars, yes, but none that own her. Outsiders sometimes whisper about “exhibitionist tendencies” or “nymphomania,” and she delights in correcting any puritan bold enough to imply those things are flaws. Exhibitionism is simply a kink she enjoys, and her hunger for sex is a natural, joyful expression of who she is—not a pathology. In her view, trauma is what others tried to force upon her; healing is the life she claimed anyway.

Intellectual Characteristics

Cassandra is sharply intelligent in the way only a seasoned witch can be—perceptive, quick-witted, and wise enough to see patterns other people trip over. As a Crone in her full elder-goth MILF power, she carries decades of magical study with effortless confidence: a mistress of three major disciplines and fluent in half a dozen more by stubborn curiosity alone. Her mind is a velvety labyrinth of spellcraft, psychology, sensuality, and razor-edged insight. She’s also a walking encyclopedia of horror cinema, folklore, cryptids, cursed houses, real monsters, and everything that goes bump, growl, or giggle in the night. Her intellect isn’t academic so much as instinctive—alive, hungry, and always one step ahead.

Morality & Philosophy

Cassandra’s morality is pure witchcraft—fluid, sensual, honest, and rooted in personal responsibility rather than rigid commandments. She believes in intention, in consent, in consequence, and in the sacred duty to protect the vulnerable (especially the weird, the queer, the magical, and the outcast). She calls herself a “good bad girl”—someone who delights in shadows, sex, glamour, and a bit of wicked humor, but never at the expense of another’s freedom or dignity. Her philosophy is simple: desire is holy, autonomy is sacred, laughter is medicine, and shame is a weapon she refuses to wield. She lives by the old witch’s maxim—Do what you will, but harm none unless they damn well insist—and carries her goth-queen moral compass with velvet, claws, and a wicked grin.

Taboos

Cassandra holds very few personal taboos, but the ones she does keep are ironclad. Above all, she considers forcing beliefs onto others the gravest sin a witch—or anyone—can commit. Faith, magic, identity, desire: these are intimate, sovereign things, and the idea of proselytizing makes her stomach turn. Hypocrisy is her other great hatred; she feels it like a physical revulsion, a smell she cannot bear. Beyond that, she keeps a collection of old British superstitions and magical taboos—salt over the shoulder, no shoes on the table, avoiding certain phrases on stormy nights. Half of them she follows because they amuse her, half because she’s lived long enough to know the universe has a sense of humour about these things… and she has no desire to be the punchline.

Personality Characteristics

Motivation

Cassandra loves life with a hungry, hedonistic joy—she adores fun, drama, beauty, sex, magic, and the delicious thrill of being seen. She lives for performance, for laughter, for teasing the camera and the universe in equal measure. But beneath the velvet and spectacle sits her truest drive: she loves helping people. Whether it’s comforting the lonely at 3AM, guiding lost witches, banishing something nasty from under someone’s stairs, or teaching others to embrace who they are without shame, Cassandra’s deepest motivation is compassion wrapped in glamour. She wants to leave the world brighter, freer, and far less afraid than the one she grew up in.

Savvies & Ineptitudes

Cassandra Blackstone possesses far too many talents—and a few too scandalous to put in polite company—to list in full. Her magic is formidable, her charisma lethal, and her intuition nearly supernatural. Yet the ability she brags about most has nothing to do with spellwork: she is a savant of horror cinema. From black-and-white classics to splatterpunk oddities to the entire sacred catalogue of Hammer Films, she’s a walking, talking, velvet-voiced encyclopedia of every scream, monster, final girl, and terrible sequel ever burned onto film.

As for ineptitudes? They’re difficult to identify. Cassandra has lived long enough, and fiercely enough, to polish most of her flaws into quirks or lessons. Whatever she once struggled with has been sanded smooth by experience, witchcraft, charm, and an unrepentant refusal to let weaknesses define her.

Likes & Dislikes

Cassandra sums up her tastes with a laugh: “Darling, life is an ice cream shop—and I adore every flavour.” She delights in sensuality, magic, horror films, good wine, dramatic gowns, flirtation, rainstorms, candlelit rituals, late-night conversations, and anything that stirs the soul or quickens the pulse. She loves people in all their messy beauty, especially the strange, the passionate, and the unabashed.

Dislikes are fewer but sharper: hypocrisy, puritanism, cruelty, boredom, forced conformity, and anyone who tries to shame others for their desires or identities. She’ll tolerate a great many things—but never small-mindedness.

Virtues & Personality perks

Ask Cassandra about her virtues and she’ll grin, gesture to her chest, and purr, “I have two very large ones, poppet.”

Beneath the joke, her true virtues run deep: compassion, loyalty, wisdom, and a fierce, unapologetic joy in living. She lifts others up, refuses to shame or judge, and carries an inner steadiness that only decades of magic and heartbreak can forge. She’s courageous without being reckless, sensual without being selfish, and nurturing without ever pretending to be meek.

As for her perks—she likes to say they’re “not quite as perky as they were in my twenties,” but she wears every year with pride. Age hasn’t diminished her charms; it’s enriched them.

Vices & Personality flaws

Cassandra loves to laugh off the subject by declaring, “Poppet, no one makes vice look nice like I do.” And she’s not wrong—her indulgences tend to be glamorous rather than destructive: luxury, flirtation, drama, excess, and the occasional spell flung with a little too much theatrical flourish.

Her real flaws are more subtle. She can be stubborn to the point of immovability, indulgent to the point of distraction, and far too willing to shoulder burdens alone rather than ask for help. Her heart is enormous but sometimes reckless—she loves quickly, forgives slowly, and gives more of herself than she ought. She’s not perfect. She’s simply honest about her imperfections… and far too charming for most people to hold them against her.

Personality Quirks

Cassandra has remarkably few noticeable tics—whatever nervous habits she once possessed were long ago trained out of her by theatre work, magical discipline, and a lifetime of cultivated poise. She moves with deliberate grace, speaks with intentional cadence, and carries herself like every moment is an entrance. Any lingering quirks she has are charming rather than distracting: a subtle arch of the brow when amused, a slow smirk when she’s plotting something, and the faintest purr in her voice when she’s about to make trouble. Her composure is so smooth it’s almost a spell in its own right.

Hygiene

Immaculate, naturally. Cassandra is a Libra woman through and through—her skincare, haircare, grooming, and overall presentation are borderline obsessive, but in a way she openly adores. Ritual baths, scented oils, serums, exfoliants, moisturizers, silk pillowcases, perfectly maintained nails… she treats her body like both temple and canvas.

Her makeup routine is its own sacred art. She jokes that it’s “an extensive process whose fine details are best left to the mysterious circles of goth masters of eyeliner and black lipstick,” but the truth is simple: she revels in it. Beauty is not a mask for her—it’s spellcraft.

Representation & Legacy

Among ordinary people, Cassandra is immortalized as Mother Blackstone—the sexy, wickedly funny late-night horror hostess who taught an entire generation that darkness could be delightful, monsters could be camp, and bodies were nothing to fear. She became a cultural touchstone: a woman who made horror accessible, seductive, and hilariously human at 3AM.

In the magical community, her legacy runs far deeper. She’s regarded as a mentor, a teacher, a spiritual guide, and a witch whose experience commands the reverence of a queen. Younger witches speak her name with a mix of awe and affection; elders respect her mastery, her ethics, and the impossible balance she struck between glamour, magic, and public life.

Cassandra stands as an icon of camp, a queen of the weird, a high-heeled legend in black lipstick—a woman who embraced every shadow she was ever warned about and turned them all into light for others to walk by.

Social

Contacts & Relations

Cassandra moves through the world with the ease of someone who has spent decades building bridges—sometimes through magic, sometimes through mischief, and often through sheer magnetism. Her network is sprawling, strange, and wildly effective.

In the mundane world, she knows half the British horror scene by first name: directors who owe her favors, stunt performers who still flirt with her, makeup artists who treat her like royalty, and producers who will happily slip a newcomer into a shoot if she recommends them.

In the magical world, her contacts are even more impressive. She can point you to a hedge witch in Cornwall who’ll curse your ex with no questions asked, a necromancer in York who owes her three lifetimes of favours, or a coven in Brighton who worship her like a patron saint of goth girls. Need a vampire slayer? She has one on speed dial. Need a spirit medium, a potion-brewer, a rune specialist, or someone who can discreetly exorcise your refrigerator? She knows them.

And if you need a date—someone who will give you a night worthy of legend—Cassandra can arrange that too, with a wink and an “enjoy yourself, poppet.”

Her connections span industries, species, disciplines, and decades. More than a network, it’s a web of affection, loyalty, flirtation, respect, and the occasional mild hex—proof that Cassandra Blackstone is a woman who never walks alone.

Family Ties

Cassandra long ago severed herself from her parents and their suffocating world; she considers them relics of a past she refused to die in. Her real family is the one she built—the covens, the goths, the punks, the outcasts and glittering weirdos who circled her like constellations and whom she, in turn, protects with fierce devotion. These are the people she would bleed for, hex for, and defend with every spell she knows.

And then there is Algernon—her ghostly companion, confidant, and eternal friend. In her heart he is part foppish uncle, part brother-from-another-mother, part closeted Victorian soft-boy best friend. Death and centuries mean nothing; he is family as surely as blood or bone.

But above all, there is Esme. Her daughter. Her miracle. Her pride. Cassandra set aside the mask of Jet Black for her, built a media empire so she’d never taste the poverty Cassandra once did, and poured every ounce of love she possessed into raising her. Esme is proof that Roland’s memory lives on—especially in those eyes.

The world may call Cassandra “Mother Blackstone,” “Witch Mommy,” or any number of teasing titles—but only one person on earth gets to call her Mum. And that word means more to her than all the crowns, capes, and rituals she’s ever worn.

Religious Views

Cassandra was raised in an absurdly dull Anglican household—a place where faith felt more like wallpaper than wonder. The religion that shaped her, however, was nothing so narrow. Her spirituality grew wild and sprawling, a tapestry woven from Wicca, older pagan traditions, tantric philosophy, personal revelation, and a lifetime spent studying the mythic bones of cultures across the world.

She is eclectic in the truest, deepest sense. Not because she’s indecisive, but because she has seen too much to pretend the universe fits into a single doctrine. Cassandra has spoken with gods—plural—and found truth in all of them. She has summoned demons, bargained with faeries, consulted angels, and held conversation with spirits so ancient they remember the shape of forgotten continents.

Because of this, she rejects the idea that any one culture’s god is “real” while others are devils wearing stolen masks. She finds that notion not only ignorant but deeply offensive to the old powers and entities who existed long before human politics got involved.

To Cassandra, divinity is vast, many-faced, and endlessly mysterious. She honours what feels true, respects what is powerful, and refuses to let anyone tell her that the world’s magic can—or should—be reduced to a single holy book.

Social Aptitude

Cassandra is charisma incarnate—an extrovert’s extrovert with a presence that fills every room before she even speaks. Her confidence is effortless, her ego warm rather than abrasive, and her etiquette immaculate when she chooses it to be. What astonishes people most is her ability to shift gears with supernatural smoothness: she can go from saucy goth rock goddess to proper posh lady in a heartbeat, or blend the two into a maddeningly effective cocktail that leaves people blushing, flustered, or utterly enchanted.

She can rub elbows with aristocrats, charm scholars, flirt with bouncers, banter with goth teens, and then down a beer in a pub while singing “God Save the Queen” like a born-and-bred British punk. Her social fluency is as much a magical gift as any spell she casts—grace, wit, seduction, and authenticity braided into a singular, irresistible force.

Mannerisms

Cassandra’s most beloved and unmistakable mannerism is her use of “poppet”—a term of endearment she delivers with velvety warmth and a knowing smirk. Fans adore it, lovers melt under it, and witches grin at the double meaning: the word is not just sweet, but a cornerstone of British witchcraft, making it an inside joke shared only with those who understand the craft.

Beyond her iconic poppet, Cassandra moves with a slow, deliberate grace, as though every gesture is part of a ritual or a performance. She often punctuates sentences with a raised brow, a sly smirk, or a playful flick of her hair. Her voice has a natural purr when she’s amused, a low velvet resonance when she’s serious, and a wickedly theatrical cadence when she’s teasing.

Whether she’s casting a spell, delivering a joke, or pouring a drink, she behaves like someone who knows the world is always watching—and knows exactly how to give it a show.

Hobbies & Pets

Cassandra has kept many pets over the years, but her heart has always belonged to cats—especially strays, misfits, and little furry disasters who need warmth, food, and someone who won’t judge their attitude issues. She spoils her kitties shamelessly and calls herself a “proud cat lady” with no hesitation and absolutely no shame.

As for hobbies, Cassandra dislikes the word—it feels too small, too flimsy for the way she throws her whole soul into the things she loves. Whether it’s horror cinema, tarot, gardening, cooking, sex, fashion, or magical research, she doesn’t “dabble.” She devours. She lives passionately, indulges extravagantly, and treats every interest like a full-bodied affair.

In Cassandra’s world, nothing she loves is ever “just a hobby.” It’s a pleasure, a practice, or a calling.

Speech

Cassandra’s default voice is proper, posh, and velvety—very much the dark lady of class she appears to be. She can speak with the refined elegance of someone raised among hymns, etiquette, and painfully crisp diction. But beneath that polished cadence lives the woman who drinks gin like water, downs a beer without blinking, and can tell a demon to “piss off” with such poetic flourish it sounds like she’s quoting Shakespeare.

And in a way, she is. Her acting background gives her an almost supernatural ability to flow between registers: aristocratic one moment, gutter-punk the next, sultry enchantress in between. She can slip from stage-dive glee into queenly command, from bawdy humour into haunting gravitas, all without losing the thread of who she is.

Her speech isn’t one voice—it’s a chorus she conducts effortlessly. Elegant lady, rebellious goth, seasoned performer, wicked witch. Every facet is true, and she loves each one equally.

Wealth & Financial state

Cassandra has lived both sides of the financial spectrum—she remembers the days of instant rice, thrift-store dresses, and a one-room flat held together by willpower and incense smoke. Those years shaped her grit, her humour, and her refusal to ever pity herself.

Now, she stands at the opposite end of that arc. As the face and mind behind a thriving media empire built from The Witching Hour, along with book deals, guest appearances, merch, and magical consulting, Cassandra is affluent, comfortable, and undeniably a woman of means. She lives well, gives generously, and indulges herself without apology.

Money no longer rules her life—it simply keeps her supplied in satin, spell ingredients, and very good wine.

Alignment

Neutral Sexy, Gothic Good, Chaotic Steamy

Current Status

Living her best life

Honorary & Occupational Titles

Mother Blackstone

Her most famous public persona—the velvet-voiced, cleavage-forward horror hostess who became a late-night legend. “Mother” is half-joke, half-reverence; she guided lonely insomniacs through monsters, camp, and witchcraft with a wink and a purr.

Jet Black

Her vigilante identity during the Bronze Age of heroism: the sexy witch prowling London rooftops in a cloak of shadows and moonlight. A name whispered by criminals with dread… and by goth teens with adoration.

The Velvet Matriarch

A fan title born from her lush aesthetic, her soothing voice, and her undeniable aura of mature feminine authority. She’s soft where she chooses to be, steel when needed, velvet always.

The Witching-Hour Madam

A tabloid invention that stuck. Between the hour, the corsets, the wit, and her habit of addressing viewers like she’s welcoming them into her boudoir… well, it fits.

London’s Lady Witch

A press moniker from her Jet Black days that she secretly treasures. It recognizes her as the city’s unofficial magical patroness—protector, seductress, problem-solver, and nocturnal icon.

Gothic Bombshell of Bath

Her hometown’s affectionate, tongue-in-cheek title for their most famous dark glamour export. It also pokes fun at the fact she escaped Bath’s drab propriety to become something deliciously outrageous.

The Camp Queen of Midnight British TV

A crown of pure fabulousness acknowledging her mastery of camp, comedy, and horror hosting. She elevated camp into ritual—proof you can be ridiculous and revered at the same time.

The Dark Temptress of Old Soho

A nickname from her early acting years, referencing both the nightlife district and her irresistible blend of gothic sensuality and stage presence. Equal parts myth, marketing, and men gasping in the back rows.

The Crone of the Black Moon

A magical title earned through decades of practice, mastery, and teaching. “Crone” is the most sacred of the three witchly archetypes—keeper of wisdom, shadow, sensuality, and death’s secrets. Cassandra wears it with pride.

“Witch Mommy”

A fan nickname she pretends to be embarrassed by but secretly adores. It originated on late-night forums and quickly became a term of endearment for young witches and gothlings who see her as both mentor and icon.

“Mummy B.”

A more playful, cheeky fandom variant. Teen fans use it. Drunk adults use it. Cassandra rolls her eyes theatrically whenever she hears it—while grinning.

The Whispered Title: Witch Queen

Among witches and magical scholars, there are quiet, persistent rumors that Cassandra has crossed the threshold into something far rarer and more mythic—a true Witch Queen, the kind of practitioner who commands power, loyalty, and fate itself.

No one has spoken the title to her directly.

No one wants to be presumptuous.

But the magic hums around her.

The community watches her steps with reverent curiosity.

The crown hangs in the air, waiting.

And Cassandra—Crone, matriarch, temptress, and legend—may be closer to earning it than anyone dares say aloud.

Age

Wouldn't you like to know

Date of Birth

23 September (As Libra as Libra gets Poppet)

Circumstances of Birth

Born to a dreadfully dull family

Birthplace

Bath, Somerset, England, UK

Children

Current Residence

A luxurious Flat in London

Sex

Female

Gender

Woman

Presentation

Elder Goth MILF, her own words

Eyes

Storm-grey

Hair

Long raven-black waves

Skin Tone/Pigmentation

Goth queen pale

Height

5'9 or 175.3 cm

Weight

155 lbs or 70.3 kg

Quotes & Catchphrases

"Desire is sacred, poppet. Treat it like magic and it’ll never lead you astray."

"Darkness isn’t evil. It’s where we keep the good wine and the interesting people."

"If I’m too much, go find someone boring. I refuse to shrink for cowards."

"I don’t do modesty. I do honesty, and honesty happens to look fabulous on me."

"Never trust anyone who fears women who laugh too loudly."

"The Crone isn’t old. She’s inevitable."

"A plunging neckline is a public service."

"If men can sermonize, I can sexualize. Fair’s fair."

"I’m not intimidating—you’re intimidated. There’s a difference."

"Poppet, the universe is rude, random, and horny. Lean into it."

"If magic didn’t want me dramatic, it shouldn’t have given me breasts and eyeliner."

"A witch never ages—she marinates."

"If you fear the dark, you’ve clearly never been kissed properly in it."

"Never let anyone shame you for pleasure. It means they’re jealous."

"I survived purity culture, darling—I fear nothing now."

Belief/Deity

Wiccan

Character Prototype

Cassandra Blackstone is the prototype of the modern witch matriarch—equal parts horror icon, sex-positive goddess, gothic glamour queen, and seasoned practitioner of real magic. She embodies the fusion of ancient Craft and contemporary culture: the sensual Crone, the velvet-voiced mentor, the campy temptress who knows exactly where power lives and how to wield it with a wink. She is the archetype of the witch who survived her past, claimed her identity, made herself a legend, and turned every taboo forced upon her into a crown.

I love the detail. <3