Zora Biology

A breakdown of some specific details of Zora Anatomy

The Zora are a rather unique species distinct from the other peoples around the globe in many different ways. Most obviously, of course, the fact that they are a race of fish* people, but one who is not very familiar with the Zora may find themselves wondering, how does this aquatic* species... work? They must reproduce somehow, but they don't wear clothes and there's not exactly anything to see 'down there'-- or anywhere, since Zora women are not mammals* and therefore don't have breasts*. To many humans, zora appear very androgynous. Like most humans, the Zora do indeed recognize two distinct medical sexes, labelled as male and female, and they have also created traditional gender classes based on those two sexes. It's just that the criteria by which this sexual division is dictated is different for the Zora than for humans, and a lot more subtle. It's not based on an individual's reproductive role like with humans, and this is of course due to the fact that male and female zora have identical reproductive systems.

This biological quirk developed rather rapidly back when they first began evolving into the 'humanoid' race they are now known to be. Zora are an incredibly diverse species-- in many outwardly visible ways, yes, but below the surface, there are innumerable physiological differences ranging all across the species. Even zora who look very similar on the outside may be very different on the inside, so much so that from a scientific perspective, the Zora could only just barely be considered as one species. They're commonly known as an aquatic race of fish people, but even such simple terms are by definition not very accurate.

First and foremost, zora are technically amphibious, since they can live both on land and in water. Many zora do live exclusively in the water, especially the ocean-dwelling domains, and even inland zora who do live on land, do not live away from water, but the fact remains that the Zora are not strictly bound to either. In regards to the whole 'fish people' generalization, not all zora are actually related to fish. Some are indeed mammals, so some zora do in fact nurse, but those who do don't have breasts like humans. They instead have slits on their pectorals which conceal their nipples (and are extremely difficult to spot unless one is looking very, very closely, but looking that closely is advised against because it's kind of rude), and the mammary glands don't protrude noticeably from the rest of the torso. And yes, this goes for both male and female mammalian zora.

Already, that's two biological categories with huge differences, but that's not all. Even among those two most prominent variations, there is still an incredible range of diversity in the base-level animal species they can be related to. There's zora based on freshwater and saltwater dwelling creatures, there's some based on invertebrates like jellyfish, there's even a distinct ethnic group on the Golden Continent whose zora ancestors mingled and mated with bulbins, and have inherited their Bulbin ancestors' frog-like traits. Then, there's the many, many different kinds of creatures a zora could be based on, just amongst fish or mammals or other things, both fresh and saltwater. They could be anything from salmon to catfish to sturgeon to trout to bass to carp to koi to goldfish to betta to piranha, to lionfish to barracudas to seahorses to tangs to mackerel to tuna to marlins to cod to char. From blue whales to beluga to orca to humpback, to hammerhead to nurse shark to tiger shark to great white, to river dolphin to spotted to striped to bottlenose.

In nature, different kinds of fish don't reproduce with other kinds of fish. But different kinds of zora, no matter how different, have to be reproductively compatible with each other, which is why despite the massive range of distinct physiology they posses, their actual reproductive systems are universal, across both type and sex. (There are some other universal traits as well, like all Zora having gills). It's not uncommon for a zora pod or village to be mostly comprised of small amounts of greatly numerous different kinds of zora, especially in rural areas. If, say, a freshwater bass zora was only able to reproduce with another of the exact same kind, but where they live, freshwater bass zora make up only a small portion of an extremely diverse population, then their family planning options would be extremely limited. Thus, it is also possible for two males or two females to have children together, or for either zora of a male/female couple to sire or carry their child, or both at once, or take turns. Think of it this way: two men or two women of the same species having a baby together really does sound like it would be a lot less complicated than a cold-blooded chordate zora from a freshwater lake having a baby with a cetaceous dolphin zora from the Great Sea. If the latter is possible, then the former could not logically be considered a strange or outlandish concept. The only thing that's not possible is for one zora to impregnate themselves.

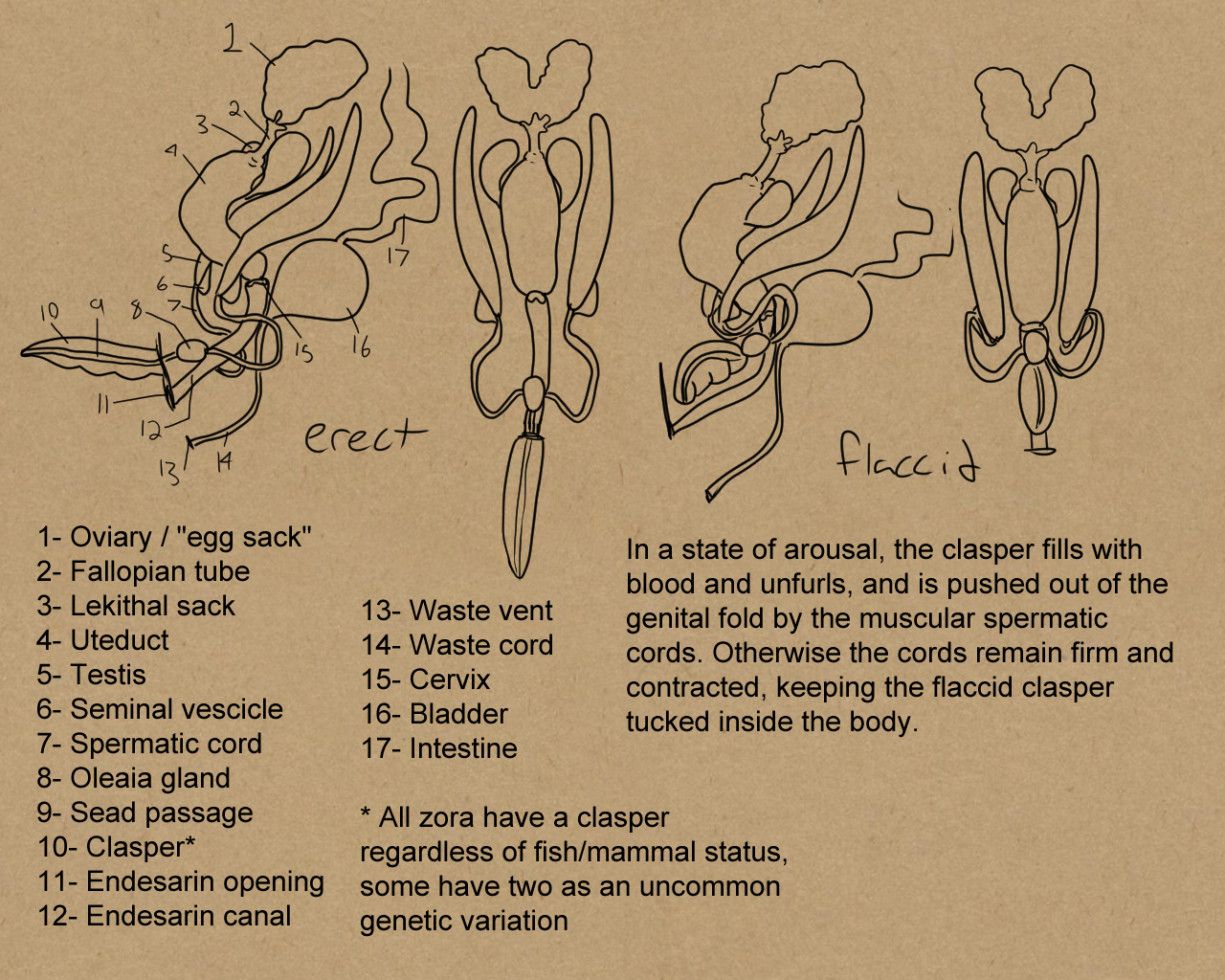

Here is a rough diagram which shows the basic configuration of the Zora reproductive anatomy:

Zora ovulate with many eggs at once a few times a year, in clutches of about ten to fifteen at a time. Zora eggs are initially very small, smaller than a marble but bigger than a pinhead, and fairly soft. If the eggs go unfertilized, they are passed and discarded. If they are fertilized via regular intercourse (the 'ins and outs' of which hopefully does not need to be explained) then they will remain in the uteduct and become encased in a gooey, placenta-like membrane which comes from the lekithal sacks. The lekithal membrane is what nourishes and protects the embryos during the brief gestation period and after they are laid, until they are hatched several months later. (From conception to hatching, the entire process takes about ten months). There are multiple different parts of the anatomy that produce the various elements that make up zora semen, like with other animal species. The oleaia gland produces 'oleaia', the oily slick substance that lubricates both the clasper itself and the sead passage, and also makes up most of the actual ejaculate fluid which keeps it from washing all away in the water.

There are drawbacks and complications, though. Evidently, putting so many different biological functions in one place does make for a very crowded, complex system. Especially since, except for during the act of sex itself, all zora genitalia is internal. It would be nice, but unfortunately, evolution is not always perfectly logical. There are numerous potential points of failure when it comes to Zora reproduction. It is very easy for zora to conceive, but it is unfortunately quite common for one to miscarry in the very early stages of pregnancy, often before the pregnancy is even detectable. Given the many risks, a zora pregnancy should be closely monitored by a doctor via regular and frequent checkups from the moment the pregnancy is noticed to the moment the eggs are hatched.

It was already mentioned that a single clutch typically is made up of ten to fifteen eggs, but zora never actually have that many children at once. Even in ideal circumstances, up to half of the eggs in a clutch won't be successfully fertilized. The eggs that are not fertilized are meant to be passed like a typical menstrual cycle, and generally the first indicator a zora may have that they are pregnant is if they notice their passed eggs are fewer than their usual cycle. However, it is possible for some or, in rare cases, even all of the unfertilized eggs to also get caught in the growing lekithal membrane along with the fertilized ones. This is very dangerous and has a high chance of leading to infection, which can severely impact the health of the pregnant zora and pose a threat to the viable embryos. If left untreated, or not caught fast enough, it is likely to result in the miscarriage of multiple or even all embryos. Only in very extreme cases has it resulted in the death of the carrying parent.

It is also to be expected for some of the embryos to be absorbed by the others, also reducing the number of eggs that will viably hatch. This will occur both during the gestation and laid periods. There's an old belief that this is the result of the carrying parent lacking nutrients and therefore producing a weaker lekithal membrane, causing the eggs to consume each other for sustenance, but in the modern day there is little scientific evidence that supports this theory, and it will happen to at least some degree no matter how well balanced a pregnant zora's diet is.

Even when an egg is not absorbed by another, some will still simply stop developing, suddenly becoming no longer viable even if everything seemed normal up until that point. There is little that can be done to prevent this, since it can happen for any number of seemingly random reasons, or even for no reason at all. Typically, by the time the eggs are ready to hatch, there will be only one to four remaining in the clutch. Twins are the most common outcome, followed by single children and triplets. Quadruplets are fairly rare. When it comes to naming their babies, zora will often have hopeful names in mind already, but it's extremely taboo to actually name the eggs before they hatch. To do so is considered an invitation of bad fortune.

Extradiagetic Notes

I went down some pretty intense etymological rabbitholes while coming up with all the terminology for that diagram, you know. ("I am the most dedicated Zelda fan ever," I say, as I try to come up with a name for the zora prostate). It's kind of funny on some level to put this much effort into information that will never actually be fully relevant to this level of detail in our actual written works, but would you believe me if I said this is fun for me? Anyways, I actually did a ton of research on marine animals' and fish reproductive biology for this, so here is a rundown of the actual list of terminology in that diagram because I couldn't find a good way to fit it into the main body of the article. I'm explaining this as if you remember the fundamental basics of your own middle school sex ed class, which you should.

That's about it for the list, I think! I looked at A LOT of different diagrams of different things to make this. I also learned some pretty crazy facts. Like how intrauterine cannibalism between gestating shark pups IS a thing! Most of the potential complications and risks described in the main article are based on the conflicting aspects of fish vs whale vs shark vs human reproduction I read up on in order to combine elements of all those into one system. Hence why zora will start off with lots of eggs and many will be inseminated (like fish) but in the end only one or two babies will actually be born (like mammals) for various reasons. One of the first big questions I had with this was does it happen via internal or external insemination, like how fish fertilize their eggs. I went with a bit of a compromise, internal insemination followed by most of the fetal development happening outside the womb.

Extras

After reading all that, you might be asking...

"What are the differences between male and female zora, then?"

Well, it's complicated, and the physical determination of assigned sex and gender at birth actually depends on the type of zora. Like with humans, there are commonly associated physical traits with either, but just like with humans, real life is never as rigid or uniform as is described in a textbook. Zora are all quite tall, though male zora are generally bigger than female zora on average, or so goes the expectation. Obviously, there are some very tall women and some very short men in the world, and a zora's height is also affected by their specific lineage. For example, Princess Ruto is about average height for a female freshwater zora. Prince Sidon is nearly ten feet tall (depending on whether you count the top of his fin or that feather he wears or not) which is way bigger than the average height of most shark zora period, and it's because his mom was a Great White and even bigger than him, and his dad is a Blue Whale and practically the size of the palace's entire throne room.

For some kinds of zora, there's the matter of how many of what types of fins someone has, or it could be down to the colouring of their scales, or pattern variations. For freshwater fish zora, only the females have those vent-like epaulettes on their shoulders. Some male whale zora have an extra muscle in their backs.

Given that it's all quite subtle and seemingly arbitrary, especially to humans, you'd probably be surprised that the Zora actually have very strict traditional gender roles. But, at the end of the day, all gender is a social construct. Just because the basis of those constructs seem silly or superfluous to someone else, doesn't mean it feels any less significant to those raised with them. Even if they themselves think so, too!

Mixed Species Reproduction

Just as zora are all as compatible as possible with each other, they also happen to be biologically compatible with other sentient 'humanoid' species. Other than the previously mentioned bulbins case, though, interspecies mating is uncommon. A zora could have a baby with, in descending order of likelihood: a Bulbin, a human, a Rito, a goron-- of the primarily groups on the Golden Continent. Like how it is amongst zora, interspecies conception is rather easy, but the actual pregnancy is even riskier, especially between zora and gorons, since their laid eggs require all but opposite conditions, with zora eggs being laid in water and Goron eggs incubating in lava. An interspecies child almost never comes out as an exact 50-50 fusion of their two parents, instead they will generally be much more of their parent who carried them. This is true for all mixed species families. Basically, if a human impregnates a zora, the child(ren) will be zora with some human traits, and if it's the other way around, they will be human with some zora traits. Both types of pregnancies are considered equally risky, even though there are technically more things that could go wrong with a zora pregnancy than a human one. It's because at least with a zora pregnancy, for more than half the process you can look directly at it with your bare eyes, and the same can't be said for humans' live births.

One of the most prominent historical figures of mixed species parentage was actually a zora. King Ralis, who was born to Queen Rutela of Zora's Domain, and King Elouan, originally a prince of Hyrule. Though Ralis may have looked like he was fully zora at first glance, there were actually many things he inherited from his father that set him apart from other, 'normal' zora. The most significant were the fact that he was born with his gills sealed shut, which meant he could not breathe underwater. Closed gills are a malformity possible of being rectified via surgery, but for that to be an option the internal structure of the gills has to be complete, which Ralis' was not. His lungs in general were rather small, and somewhat weak. The cartilage in his headtail and fins were also harder and more rigid than they should have been, more akin to the kind that makes up a human nose. This meant his fins were not very flexible, and his headtail was completely stiff and stood straight up in the air rather than hanging down behind his head. Because of all this and some other minor issues with his bone density and skeletal structure, Ralis was a very sickly child and a poor swimmer all his life. However, none of that actually stopped him from becoming a great king and accomplishing monumental things, as he was the one to lead Zora's Domain into it's flourishing modern era, and laid the foundations for his people's prosperous future. Even ten thousand years later, he is still remembered as an important figure in zora history in general as well as specifically the history of disabled zora.

Comments