The Congo Basin holds its secrets close. Here, in one of Earth's last true wildernesses, the line between legend and reality grows thin, obscured by morning mist and dense canopy. For centuries, tales have emerged from these waterways of something extraordinary - a creature of impossible size that has eluded scientific documentation despite countless expeditions seeking to prove its existence.

It’s been called The Mokele Mbembe.

I've investigated many creatures that blur the line between myth and reality. But something about these waters feels different. The dense canopy above creates a permanent twilight below, where ancient rivers wind through terrain that hasn't changed in millions of years. Here, the people don't speak of monsters in whispers or tales - they describe their encounters with the calm certainty of those who have learned to share their home with something extraordinary.

What we discovered in those swamps would reshape our understanding of what might still exist in Earth's unexplored regions. And perhaps, whether some mysteries are better left undisturbed.

The Background

The Congo Basin is a vast expanse of unexplored wilderness that could swallow entire nations. Even today, new species are discovered here with startling regularity. But at this time, my team and I weren't searching for something new, but something supposedly very old–a creature that had been documented, albeit sparsely, for nearly two centuries–and if the legends were true, the creature was far older than that.

The idea of a “living dinosaur” in this region took hold in the 1920s, when sensational headlines compared local accounts to sauropod dinosaurs like Diplodocus. Western explorers latched on to the idea of finding a prehistoric behemoth alive and well in Central Africa, but in doing so, they often glossed over local insights that didn’t align with their dinosaur-centric theories—potentially missing clues that the truth was far stranger and more nuanced than a single, ancient surviving species.

Others have dismissed the accounts entirely–equally problematic given the wealth of relatively consistent local knowledge spanning generations.

In fact, the earliest Western record dates back to 1776, when missionaries noted colossal footprints—each three feet in circumference—trailing into murky waters. Over the centuries, colonial officials and local hunters alike described a huge creature lurking in the swamps, yet the details conflicted. One report claimed a towering, long-necked herbivore; another spoke of a lethal aquatic predator that dragged its victims beneath the surface.

I must admit that when our department first received reports from the region, I was skeptical. Even in general, the Congo has become something of a lightning rod for... sensational claims.

Even so, we made the journey, and were met by our appointed guide, Emmanuel, at a small airstrip near the Likouala swamps. Over the next week, as we conducted interviews, he would serve as our interpreter. We came to see that while the locals’ accounts were diverse, they did appear to reveal a pattern.

The hunters who worked the riverbanks spoke of a peaceful giant that fed on vegetation. But those who ventured into the deeper channels told different tales - of immense shadows beneath the water–something that if it chose, could snap a fishing boat in half.

It was with these images swirling in our minds that we finally embarked on our expedition proper, in traditional dugout canoes.

And as our small fleet pushed deeper into the Likouala, I couldn't shake the feeling that we were being watched. The Congo Basin contains over 500 million acres of wilderness. Entire ecosystems exist here that have never been properly documented. Even new species of large primates were still being discovered.

What else might live here, in isolation, entirely hidden in these unexplored waterways?

A sudden movement from Emmanuel caught my attention - he had stopped paddling, his eyes fixed on something along the muddy bank. Following his gaze, I saw what had given him pause: a series of distinctive impressions leading into the water. The tracks were fresh, the mud still settling in places where water had seeped into the depressions.

As we carefully maneuvered our canoe closer, I could see they were quite unlike anything I’d seen before. Whatever had left them was obviously quite large, but the impressions were distributed in an odd pattern that didn’t immediately resolve itself in my mind.

As the mists of the morning rolled across the calm waters all around us, a tingle ran up my spine, and I realized even then that we were standing on the verge of a new discovery.

Whatever had left these tracks was no mythical beast, but nor was it a living fossil - and yet, it had managed to remain hidden from science for centuries.

But as I would soon discover, it wasn't the only thing hiding in these waters.

Initial Investigation

Our investigation began along the outskirts of the swamp, where we rose before dawn and lingered past dusk, hoping to catch any sign of movement in the half-light. The air was thick with humidity and the calls of unseen creatures—a constant reminder that we were intruders in a land that seemed frozen in time.

The tracks we'd discovered led us to clearings, where more signs of large animal activity were unmistakable. We observed large swaths of stripped vegetation, and always accompanied by those same distinctive prints.

I found myself craning my neck just to see where leaves had been stripped—nearly twenty feet above the forest floor. No elephant or known creature in the region could achieve that reach. The trunks bore deep gouges, left by something of immense force.

Soon, however, our documentation of these land-based signs was interrupted by new reports from local fishermen. Several had abandoned their usual fishing grounds in the deeper channels, speaking of nets torn apart with clean, powerful bites.

At first, we dismissed these accounts as peripheral to our investigation. The creature we tracked, after all, seemed to have little direct interest in the waterways, seeming to prefer to move between forest clearings where it could access high vegetation.

But about three weeks into our observations, we heard a massive disturbance in a nearby channel - not the typical splash of a hippo or crocodile which to some extent had begun to fade into the background of our studies, but something that displaced an enormous volume of water.

We rushed toward the sound, but by the time we arrived, all that remained were ripples, large swells lapping at the shoreline.

And nearby: the partial remains of what appeared to be a young forest buffalo, cleanly severed.

I felt then the first stirrings of an unsettling realization. Could the same legend that described a gentle giant also contain a fearsome killer? The answer wouldn’t come easily—or quickly.

The Discovery

Our first real breakthrough came from a single, unexpected clue. While surveying another feeding site, I noticed what looked like reptilian scales caught in the bark of a fallen tree—each one nearly the size of my palm. At first glance, this seemed to confirm the traditional tales of a dinosaur-like beast.

But detailed inspection revealed that, surprisingly, these weren't scales at all–at least, not in the traditional sense–but modified hairs, compressed and hardened into overlapping plates. Though their size was certainly unprecedented, their internal structure and composition was unmistakable.

It was only few days later, in the twilight of early morning, that we would finally discover what had left them.

Drawing on the patterns of half-eaten foliage and those scattered ‘scales,’ we staked out a clearing just before dawn. The forest stirred with quiet anticipation. Then, without warning, branches high above began to sway—as though some colossal weight were moving among them.

But this was no dinosaur, nor even a reptile–but a very clearly a mammal.

Pangolin Biology

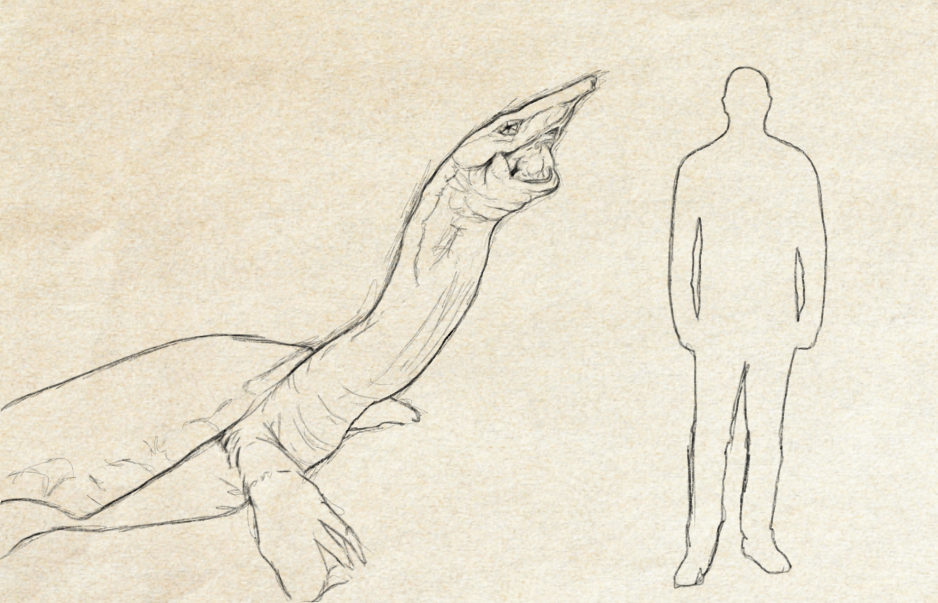

The evidence before us left no room for doubt. We were observing a new species of pangolin, one that had achieved truly extraordinary proportions. I have designated it Potamanis giganteus.

Initial examination of our specimens confirmed what those modified scales had suggested. While retaining the fundamental characteristics of the family Manidae - the keratinous scales, elongated snout, and powerful limbs - Potamanis giganteus, of course, differs greatly in terms of scale.

The largest living pangolin, the aptly named Giant Pangolin, rarely exceeds four feet in length, yet our specimens reach up to fifteen feet from snout to tail. Based on our photographic analysis and track measurements, I estimate their weight at approximately 2,000 pounds - comparable to a small African elephant.

It goes without saying that supporting this extraordinary mass required fundamental changes to the pangolin body plan. Most notably, the limb bones have become distinctly columnar, more reminiscent of elephants than typical pangolins.

Limited examination of skeletal remains we would discover later revealed dramatically increased bone density and complex internal structures that apparently house extensive blood vessel and nerve networks.

Additionally, the articular surfaces of the joints, particularly in the ankles and knees, are notably broader than in other pangolins, effectively distributing the creature's massive weight, even when the animal reaches upward to feed, transferring thousands of pounds of pressure through its hindlimbs. Yet despite its imposing size, giganteus’ movements are surprisingly… graceful, moving through the thick jungle foliage with efficiency, often leaving little trace of its passing other than in its feeding grounds.

And like all pangolins, giganteus is covered in unique, plate-like structures formed from modified hairs and composed primarily of keratin. However, rather than the comprehensive armor seen in modern pangolins, where scales overlap like medieval plate mail across the entire body, giganteus exhibits heavy scaling primarily along its dorsal surface, with reduced coverage along its flanks and limbs, and almost none on its ventral surface.

The scales themselves, while fewer in number, are proportionally massive - reaching up to ten inches in diameter. Each appears to be deeply anchored in thick dermal layers by extensive collagen networks, allowing for both structural integrity and the flexibility needed for movement.

It seems that this reduction in overall armor coverage serves multiple purposes. For example, a creature of this size has little need to armor itself from predators. Instead, its two primary challenges would be heat regulation and weight management.

The former point seems to be addresses by specialized folds of skin between the scales, particularly around the neck and limb joints, which contain dense collections of blood vessels.

Indeed, by reducing its ancestral armor in favor of more efficient heat management, giganteus was able to achieve and maintain its remarkable size.

At this point, my valued reader, the question was simple. What could drive such a momentous shift from the ancestral, much smaller pangolin form, to what we now saw before us?

Though much more study will be needed to know for certain, it is my belief that at some point, this lineage found itself relatively isolated. As climate fluctuations began altering the African landscape. Certain populations adapted in unique forest refugia - pockets of dense vegetation where high-canopy food sources remained abundant year-round. In these isolated habitats, this lineage assumed a niche with little competition for upper canopy resources.

Traditional pangolin adaptations for insect-feeding - the long, sticky tongue, specialized stomach, and powerful digging limbs - would have initially served these populations well enough.

But in an environment where higher calories were available in the form of leaves and fruits, any ability to access these resources would have provided a significant advantage. Over time, those individuals capable of reaching and processing plant matter began to dominate these isolated populations.

And indeed, other than its size, this shift from the insectivorous diet of its relatives is perhaps its most impressive change.

We were able to ascertain that while giganteus retained the muscular walls typical of pangolin digestive systems, the stomach had developed distinct regions specialized for plant digestion, with extensive folding and increased surface area when compared to insectivorous pangolins, and distinct areas for mechanical and chemical breakdown of plant matter.

The small intestine exhibited elongated villi and more numerous microfolds, adaptations that likely increase retention time of plant material and enhance nutrient absorption capability.

Furthermore, tissue samples showed mitochondrial densities more characteristic of large herbivores than insectivores–a fundamental shift in how these creatures process energy, and which ultimately has facilitated their immense size.

Unlike their smaller relatives, these giants appear to be primarily solitary, with territories spanning several square kilometers. Based on track patterns and feeding site distribution across the basin, we estimate fewer than 200 individuals remain in these isolated forests.

With giganteus well documented, I expected our work in the region would begin to draw to a close. But even then, something continued to nag at me. While our peaceful browser explained many elements of the Mokele-mbembe legend, it couldn't account for the more troubling reports and certain first-hand… oddities… that we'd encountered.

The Mysteries Deepen

Even so, the discovery and documentation of giganteus did help to explain many elements of the local legends that had drawn us to this region. The immense tracks described by those early missionaries, the reports of a long-necked creature able to reach into the highest branches, the timeframe of most sightings often at dusk and dawn–all could be attributed to this remarkable pangolin species.

Some artwork attributed to the region even seemed to be a nearly exact representation of this very creature.

But during our historical research, we had encountered other accounts that didn't fit this picture. Tales of predation unlike anything the local crocodiles or hippos were known to attempt. Stories of fishing boats damaged by powerful, precise bites.

And the image of that forest buffalo, its body cleanly severed, never left my mind.

Slowly, new evidence began to reveal itself. The first appeared early one morning at a fishing camp - a dugout canoe pulled from the water, its hull punctured in a distinctive pattern. I had documented damage from hippopotamus attacks before - chaotic crushing and splintering. This was different. The holes were clean, precise, arranged in an arc that suggested a single bite from something with remarkable jaw strength.

This was why local reports had seemed at times to be so inconsistent. There was a distinct possibility that the legend of the mokele mbembe had not arisen due to a single unknown species... but two.

But documenting an aquatic predator of this likely size would require a fundamentally different approach. We relocated our base of operations to a series of platforms over one of the deeper channels, installing a network of infrared cameras and pressure sensors, along with hydrophones capable of detecting the subtlest underwater movements.

For three nights, our recordings captured little more than typical nocturnal stirrings—crocodiles slipping into the current, distant splashes of fish. On the fourth night, however, a massive form breached the surface. At first, it resembled a smooth boulder rising from the depths—until we realized it was an enormous shell, at least nine feet across. Then it moved, and in that moment, we knew: we’d found our monster.

The Reveal

What we observed that night was, shockingly, a softshell turtle of unprecedented proportions, which I have named Gigantrionyx vorax. I estimate that the specimen before us that night measured roughly nine feet across its carapace, with a total body length approaching twelve feet. The massive skull, approximately two feet in length, even bore the distinctive tubular snout characteristic of the family Trionychidae.

And yet, despite its enormous size, the creature moved silently, each movement precisely controlled as it oriented itself in the channel. When it turned, the displacement of water was so significant that our observation platform swayed.

Unfortunately, my team and I were so stunned by this creature’s sudden appearance that we scarcely had time to react. The creature itself must have sensed something, for just as quickly as it had appeared, it sank once more beneath the surface and retreated, leaving barely a ripple in its wake.

We searched for several more nights to no avail. But I was not content to leave without an opportunity to examine this creature in full. We expanded our search, stretching our resources thin.

Turtle Biology

And then, at long last, we came upon another vorax specimen. The massive turtle lay beached in a shallow tributary, clearly deceased. Judging by the deep laceration across its shell and the signs of infection along the edges, it had likely succumbed to injuries sustained in an earlier confrontation. The carcass was still fresh, a rarity in these warm, acidic waters where scavengers and rapid decomposition ensure that most remains vanish within days. Aware of how brief this opportunity would be, we swiftly collected measurements and tissue samples, determined to learn all we could before nature reclaimed the evidence.

This specimen was notably smaller than the one we’d glimpsed previously, though still unprecedented among its relatives–to date, the largest known softshell turtle, the yangtze giant, is known to reach shell lengths of just over 40 inches.

The shell of this specimen measured 7.8 feet in length, with a total body length approaching ten feet. Its skull structure was far more robust than typical softshells, with reinforced attachment points for jaw muscles that must have generated extraordinary bite force. The head itself was massive, approximately 16 inches in length.

And though vorax clearly shared the basic body plan of other softshell turtles, the specimen’s entire morphology indicated a level of predatory specialization far beyond any known species.

The shell itself, while maintaining the characteristic leathery texture of softshells, was notably thicker and more heavily reinforced, rendering the term "softshell" somewhat misleading. The underlying bone structure was markedly thicker than in comparison to other softshells, with more pronounced buttressing between the carapace and plastron, and denser connective tissue throughout. All of these reinforcements appear to be necessary adaptations to support the creature's massive size.

As with giganteus, the question of how this creature attained such proportions has yet to be fully answered.

Still, I hypothesize that at some point in its history, this lineage diverged from its smaller relatives, likely in response to the rich hunting opportunities these channels provided.

The carapace, while retaining the characteristic flattened form, developed more pronounced hydrodynamic contouring, with a leading edge that apparently reduced water resistance during high-speed attacks. The limbs became extraordinarily powerful, with massive muscle attachments and elongated digits supporting extensive webbing.

In the forelimbs, enlarged swimming muscles provided exceptional power and control - likely crucial for maintaining position, especially while striking onto the shore during ambush attacks.

And indeed, this species’ increase in size appears to have dramatically expanded its predatory capabilities. While all softshell turtles can be aggressive predators, vorax's sheer size allows it to target prey far larger than any other species would attempt. The bodies of water in the Congo Basin apparently provided perfect conditions for such a large ambush predator to arise–abundant prey, minimal competition, and countless hidden approaches from which to strike.

And this is where the legend of Mokele-mbembe began to make even more sense.

Vorax's jaw structure clearly indicates that it is capable of immense crushing power, with enlarged attachment points for temporal muscles, as well as a heavily reinforced skull and sharpened beak thickened at key points of potential stress.

This certainly helps explain the reports of boats being splintered from below.

This powerful bite was made even more effective by the creature's extraordinary neck structure. While all softshell turtles possess relatively long necks, vorax's cervical vertebrae showed more pronounced muscle attachment points and interlocking joints that apparently enhances both striking speed and power, much like the spring-loaded strike of a snapping turtle–but scaled to admittedly intimidating proportions.

Given the vastness of these waterways and the creature's elusive nature, I can only theorize about population numbers. The channels and deep pools of the Likouala could potentially support a significant population, but confirming this would require far more extensive surveillance than our brief window of study allowed. What we did observe suggests they are most active during twilight hours, when reduced visibility gives them maximum advantage in ambush hunting.

Ultimately, while Gigantrionyx vorax and Potamanis giganteus bear little resemblance to one another, each has developed morphological traits that do parallel those of certain extinct megafauna, and observers unfamiliar with the region’s extant fauna might easily fuse elements of both species into a singular “long-necked, giant-bodied” beast. The pangolin’s towering stance and elongated cervical region could be interpreted as a “sauropod neck,” whereas the turtle’s extended neck and distinct shell certainly evoke the image of a prehistoric reptile.

These may be sufficient to explain how centuries of local knowledge and sporadic Western expeditions converged into the legend of Mokele Mbembe. In truth, the local people had long recognized them as two separate entities. Yet once filtered through the lens of colonial explorers—eager to discover “living dinosaurs”—these scattered sightings merged into a single legend.

It is not difficult to envision how the waterborne sightings of an immense shell might seamlessly mesh with glimpses of an upright form wading along the swamp, eventually culminating in rumors of a solitary monster possessing traits of both mammal and reptile.

Conclusion

Two remarkable creatures became blurred into one myth, each reflecting different facets of the Mokele Mbembe legend. For generations, local knowledge kept them hidden. Even as rumors spread, claims of a “living dinosaur” only pushed serious inquiry aside—most dismissed the reports as folklore or hoaxes.

But now, that secrecy is gone. My official report has left my hands. What was once myth has become flesh, bone, and data. By making their existence known, I fear that I may have turned these ancient inhabitants of the Congo Basin into vulnerable targets.

Standing on the airstrip, I sensed the gravity of what we’d done more than ever before: we had peeled back another one of Earth’s mysteries, and the consequences are just beginning to unfold. The question is no longer if Mokele Mbembe is real, but how long these creatures can survive. As the last crates of equipment were loaded onto the plane, I realized we might have destroyed their only protection—leaving them exposed to whatever comes next.

Watch the video here:

Comments