The Devouring Garden

CHEN Transmitting: 18:42 local time – Signal Stability: Intermittent

"Miller fell asleep during his shift. This morning we found—vines" STATIC "—wrapped around his ankle, up into the sleeping bag. It didn’t even wake him. The rate of growth is astonishing—"

DISTORTION

"Rodriguez finished the translation. Apparently the carvings along the eastern wall show human forms inside... something. We thought they were symbolic, but the proportions... the anatomical detail..."

STATIC

"The clearing is shrinking. We're activating containment protocols. But I don’t think we can stay here. I keep thinking... what if they're not meant to keep things out? What if—"

SIGNAL LOST

That was the final recording received from Dr. Lin Chen, a biochemist with fourteen years of field experience. She published papers on extremophile bacteria. She had a reputation for methodical, careful work.

Which made what happened at that temple all the more disturbing.

The official report blamed a flash flood. Early storm season. This explanation would have satisfied me if the meteorological data hadn't shown only moderate rainfall for the entire month. If the equipment hadn't been carefully packed and powered down.

And if Chen's final transmission hadn't mentioned containment protocols.

And so it was that my team and I were dispatched, sent to investigate the disappearance of Chen's archaeological team.

In my years of study, I've encountered organisms that push the boundaries of known science. Creatures that challenge our taxonomic classifications, even require entirely new theoretical frameworks.

But what I found at that temple...

Well. It was certainly no creature.

We landed at a regional airstrip five days after the company lost contact with Chen’s team. The journey to the site took another two days—first by Land Rover through progressively deteriorating roads, then on foot when the jungle reclaimed even those.

Our guide was a man who'd worked with archaeological teams for two decades. He stopped at a creek bed six kilometers from the temple and refused to go further. The locals considered the area forbidden, he said, and had for generations. When we asked for specifics, he only repeated the same phrase: "tierra hambrienta.”

Of course, I'd heard similar warnings at other sites. Usually, they were cultural memories of real but mundane dangers—unstable terrain, disease vectors, predator territories. But the fear in our guide's expression was… deeper.

Over the years, I’ve come to believe that there are places where our understanding grows thin. Unscientific, perhaps. But standing at the edge of that green wall, listening to the jungle's complete silence. Well, I couldn't entirely dismiss the observation.

The hike to Chen's camp should have taken three hours. It took five. The jungle resisted our progress, and by the time we glimpsed the temple's uncovered stone crown rising above the canopy, it was late afternoon.

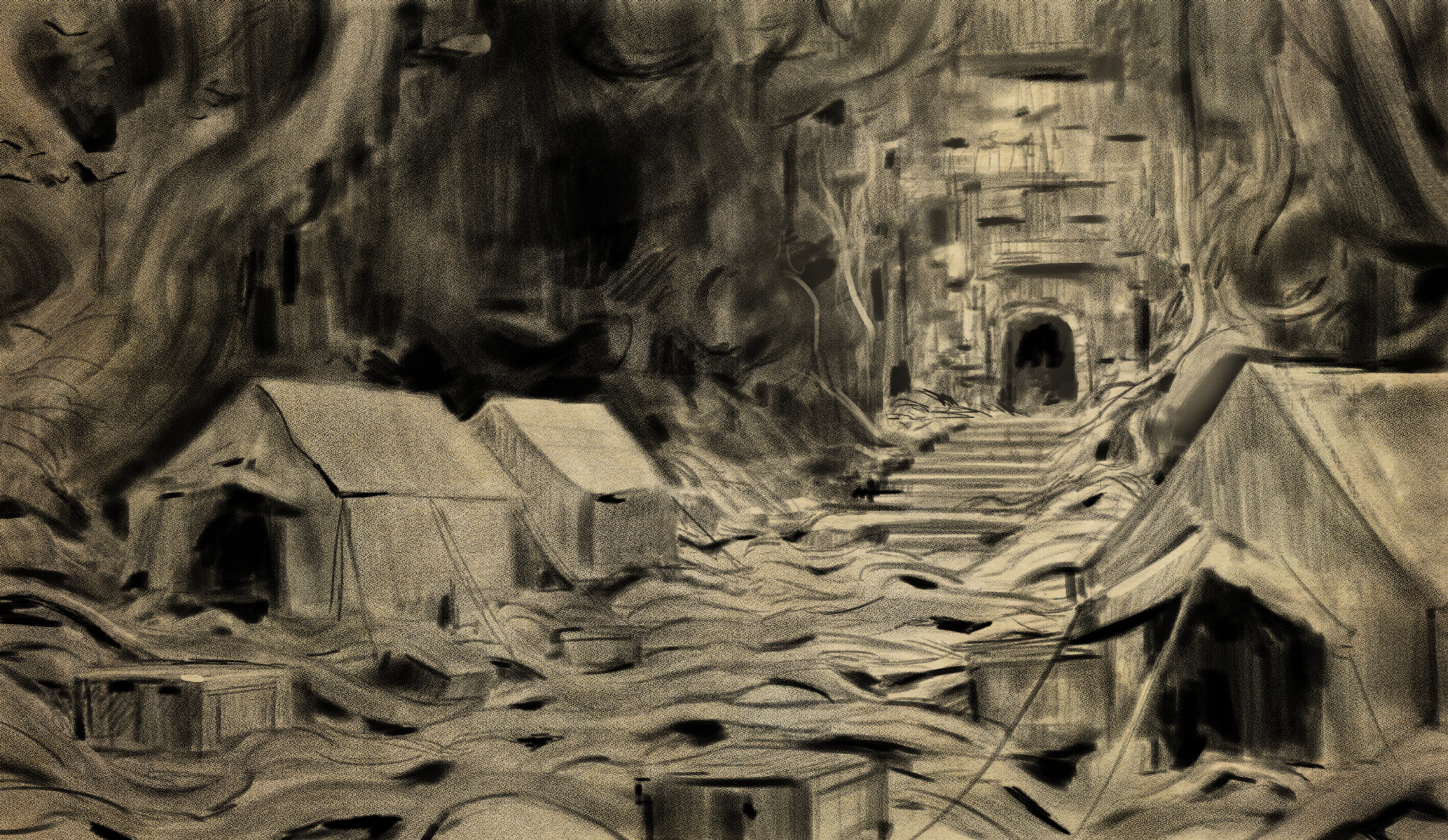

Chen's base camp spread across a cleared area fifty meters from the temple entrance, already being reclaimed by plant growth. At first glance, nothing seemed truly amiss. Tents stood in neat rows. Solar panels were angled toward breaks in the canopy. The kitchen area remained organized, supplies stacked in waterproof crates marked with inventory numbers.

In the central tent, we even discovered Chen's field notes open on her desk, her last entry dated the morning of her final transmission.

In short, there were no signs of distress or panic.

And yet, the only signs of life here were the plants, pressing into the clearing from all sides as though they were eavesdropping on our hushed conversations.

Something felt… off.

It took some time to realize what it was.

Other than the whisper of wind through the trees, this area was completely silent. No bird calls. No droning insects or distant whoops of primates.

Only once did something break that stillness—a low creaking, almost like ship's timbers straining. But wet. Organic. It seemed to come from everywhere and nowhere, lasting maybe five seconds before silence reclaimed the space. We made note of it and moved on.

We only had five hours of daylight remaining, and I made the decision to begin our survey immediately, beginning with the temple that loomed before us, its entrance a carved mouth in the hillside that seemed to swallow light.

The corridor of that entrance sloped downward, and our flashlights carved only weak cones into its depths It felt less like a hallway and more like a throat, the air thick, humid—digestive.

We went in, hoping to find answers. But for now at least, all we’d find were more questions.

The Investigation

It was hard to tell just how old the temple was. It was made of stone blocks fitted without mortar, worn smooth by centuries but showing no signs of structural weakness.

It was strange, but the entire architecture seemed to be designed… backward. Defensive positions faced inward. What were undoubtedly channels for drainage ran uphill.

And about 20 meters into the descent, we began to see carvings on the walls.

Now, typical Mayan iconography emphasizes human figures and celestial bodies. But in these, human forms were relegated to the margins.

Center stage belonged to... something else. Botanical motifs, certainly, but rendered with unusually precise anatomical detail. There were cross sections of what appeared to be seed pods, and root systems mapped like circulatory diagrams. And those human figures throughout—though small and secondary.

Flashes rang out through the darkness as Alison documented the glyphs, each one like the blow of a hammer in this enclosed space.

I noticed that one of these reliefs depicted human forms arranged inside what appeared to be pods or chambers. The detail was extraordinary. The kind of accuracy that comes from intimate knowledge.

That night, we established our own camp at what we judged a safe distance from both the temple and Chen's site. The protocol was standard: establish a perimeter, set a watch rotation.

I woke for my shift at 0300. The air was cooler now, misty, our own clearing now barely illuminated by moonlight. And that pervasive sense of… complete silence. It was then that I noticed… or thought I noticed… the edge of clearing seemed closer to my tent than it had before.

At the time, I thought that ridiculous. A trick of the pale light and fog, or a misremembering.

We found Chen's field notes the next morning, sealed in waterproof containers near the main tent. Her early entries clearly conveyed the excitement of discovering an unknown cultural subset. But by Day 8, her tone had changed.

"Rodriguez insists the root systems are expanding. I didn’t believe it first, but daily photographs confirm it. We calculate a growth rate of roughly 2.3 cm per hour during peak periods. Impossible."

Day 12:

"Miller woke up yelling last night. Growth had reached the interior of his tent, around his sleeping bag. We cut it away easily but regrowth reached same position within four hours. I noted unusual swellings at distal tips. Not consistent with leaf or bud formation. Possible reproductive structures?"

Her final entry, scrawled in deteriorating handwriting:

"The clearing is shrinking. Measured it this morning. Eight meters lost on the north side alone. How did we not notice before? Perimeter now at 12 meters. If rate continues, complete enclosure in 72 hours. We will attempt extraction at dawn."

I closed the journal as the morning sun struggled through the canopy. Around us, the jungle maintained its unnatural quiet. My pulse quickened as I thought back to those early morning hours. Had our perimeter always been this small? When we'd arrived three days ago, hadn't there been more space?

Marcus was already measuring. His expression told me what I'd feared. Somehow, we'd lost two meters. Uniformly. On all sides.

The Discovery

By our fourth day, Marcus had begun to track the encroachment patterns, even creating a map of the growth.

Hoping to learn more, we determined to follow a particularly dense growth zone that led deeper into the jungle east of the temple. The path wound between buttress roots and through dense undergrowth. Twenty meters in, the forest floor changed. Became softer. Spongier.

We found the bones in a natural depression, perhaps three meters across, like a bed of interwoven roots. Animal remains first—small mammals, their skeletons intact but strangely eroded. The bone surface showed what appeared to be chemical weathering.

I’d seen similar erosion patterns before, but in a lab—a kind of pitting that occurs when bone tissue is suspended in proteolytic solution.

Alison once again began to document the scene, and I took a careless step toward the depression.

The response was instant. The underlying network of plants, what I’d taken for thickened roots, contracted inward with a wet snap, enclosing the era just in front of my boot faster than a blink.

It was like a Venus flytrap, but as we’d come to discover, the trigger zones extended for meters.

My one misplaced footfall had activated a single contraction. But there were certain to be more trigger zones, perhaps all around us.

To my… discomfort… I realized that we were standing in a biological minefield.

And it was then that Alison spotted the human remains. A skull, partially buried, showing those same patterns of erosion, patches of scalp still clinging to degraded bone.

We photographed everything. Measured the depression. Took samples of the soil, and of the plant itself. But as we documented the scene, I became aware that the growth around the depression had shifted since our arrival.

We retreated carefully, retracing our steps as best as we could. And that sound… that wet creaking… followed us all the way back to camp.

When we arrived, our clearing had become even smaller. Large tendrils of vine now extended from the jungle’s edge, snaking along the ground toward our tents like fingers feeling blindly in the darkness.

Traps were one thing. Though we saw no perceptible movement, I couldn’t shake the feeling that now, we were being hunted.

Biological Mechanisms

When confronted with horror, the scientific mind seeks refuge in methodology.

And so we were all more than willing to spend the next six hours establishing a field laboratory, processing samples, and applying the framework of botanical science to something that by all accounts defied easy classification.

Still, for the purposes of study, I have called this species Pseudoyateveo sanguinaria.

Now, it goes without saying that plants, by their nature, make poor predators. Rooted in place, they rely on prey coming to them.

The Venus flytrap achieves this with sweet nectar, snapping shut when trigger hairs detect an insect. Pitcher plants create slippery death traps filled with digestive fluid. Sundews use adhesive tentacles.

But those plants feed on insects, small frogs at most. Legends of man-eating plants—like the Madagascar tree that supposedly consumed humans, the Ya-te-veo with its flailing vines—have always been dismissed as colonial fantasies.

But even our first tissue samples challenged all of those assumptions.

The cellular architecture certainly resembled known carnivorous plants—perhaps modified from the order Ericales—but the scale was wrong. Whereas a pitcher plant's digestive glands might span millimeters, these structures extended through entire root systems. I also noted thick-walled cells clustered at certain nodes, their purpose unclear. They reminded me of the pressurized cells in the seed pods of Impatiens, but far more robust.

The enzyme concentrations in the soil explained the bone erosion patterns I'd recognized from my laboratory work. These proteins didn't just break down tissue; they liquefied it. We observed proteases that could cleave peptide bonds not in days, but mere hours, and phosphatases that extracted calcium from bone.

A mammalian body trapped by one of these plants, would dissolve completely, every useful molecule absorbed and transported through the root system. Even one as large as a human.

We had learned much of this plant’s digestive process, but we hadn’t yet determined how it trapped its prey exactly.

Our answer came from Marcus’ detailed tracking of overnight growth.

You see, normal vines climb through a process called circumnutation—they spiral slowly, eventually finding purchase on some higher location. I'd briefly studied this in Convolvulus, watching time-lapse footage of morning glories tracing lazy circles as they grew.

Sanguinaria was different.

It telescopes, so to speak, from specialized nodes—much like bamboo, which can grow up to 35 inches in a single day—through cell elongation rather than division. Pre-formed cells simply expand by pumping in water.

This organism had developed a similar mechanism, but retained flexibility. As Chen had noted, new growth could extend an astonishing 2.3 centimeters per hour—all while remaining as pliable as a vine.

We tested it. A heated stone placed ten meters from visible growth attracted rootlets within six hours. They grew directly toward the heat source, deviating only to avoid obstacles.

Under the microscope, we saw observed what appeared to be modified TRPV-like channels—the proteins that let your tongue detect the “heat” of spicy food. But these responded to ambient temperature differences of just half a degree.

In short, any warm-blooded animal that lingered—sleeping, resting, dying—would inevitably attract growth.

I thought of Puya raimondii, the Queen of the Andes. A plant that spends decades as a spiny, silent spike—then in response to a precise convergence of warmth, altitude, and time, flowers once and dies.

The comparison was imperfect, of course. But I couldn’t shake the feeling that this organism had also been… waiting.

And each night we slept, we were training this organism exactly where to extend its hunting network.

Of course, none of this growth would matter if Sanguinaria had no way to restrict its prey from escaping.

But it most certainly does—and the trigger mechanism I'd discovered by accident proved to be astoundingly sophisticated.

In plants, structural support is provided by turgor pressure—water pushing against cell walls. It's why lettuce wilts without water.

The motor cells in Mimosa pudica, for example, use controlled turgor loss to fold leaves when touched, pumping out potassium ions so water follows by osmosis. The whole process takes about a second.

In Sanguinaria the same principle had been weaponized. When I stepped on that specialized root zone, thousands of motor cells had simultaneously opened ion channels. Water rushed out.

By my estimates, the cells collapsed in approximately 120 milliseconds—faster than human reflexes. But where Mimosa's response ends there, in Sanguinaria, this created a vacuum that pulled surrounding tissue inward. Adjacent trigger zones, suddenly stressed, fired in sequence.

I watched Marcus demonstrate with a branch, dragging it across a carefully selected region of the forest floor. The contractions followed the movement like a wave, each trigger activating the next. Even a running animal would face cascading collapses from all directions. The faster it fled, the more triggers it hit. The more it struggled, the tighter the entanglement became.

It was the perfect trap.

But it wasn’t until our fifth day that the true scope of the organism would reveal itself.

Marcus had understandably been troubled by his measurements of encroachment patterns, and he convinced me to unpack the ground-penetrating radar we'd brought for mapping the temple foundations.

He set up the equipment at the edge of our shrinking perimeter.

In short, these scans indicated that what appeared on the surface as scattered growth zones were in fact connected by rhizomes the thickness of my arm, some extending hundreds of meters underground.

We spent the next few hours mapping, carefully moving the radar in systematic transects. Each pass revealed more connections.

This was not a colony of individual plants, as we had assumed. It was a single organism spanning at least four hectares.

It was, in some ways, like Pando, the ancient clonal aspen that covers 43 hectares of Utah.

I traced the connections myself, injecting fluorescent dye at one location. Within an hour, traces appeared at sampling points throughout our mapped area. The transport occurred through specialized vascular tissue at nearly a meter per minute—far faster than typical plant circulation.

And when we triggered contractions at the north edge, thermal imaging showed metabolic increases at the south within twelve minutes. It appeared that the entire organism could direct resources toward active hunting zones.

Throughout this process, a question had been nagging at me. Why hadn’t this plant been documented before? Was it isolated to this precise location?

It gradually became clear that Sanguinaria requires specific conditions—limestone substrate, humidity above 80%, stable temperatures. It was likely difficult to spread beyond this very valley. Though, certainly not impossible.

Likely for millennia, it had survived here, perfecting its strategy on whatever entered its domain.

Other populations might exist in similar pockets. But this one, we were beginning to understand, was different.

At some point, we became struck with our own predicament. The clearing was shrinking, that much had been clear. But now, we were seeing just what that meant. And if we were to linger much longer, well, it may not end well for us.

And yet, we had to know more. To understand.

With a sense of urgency, we decided to return to the temple.

We descended again into those carved corridors, but now with different eyes.

Alison had been photographing the glyphs since our arrival, but their meaning had remained opaque. The botanical motifs dominated every surface—roots, vines, pod-like structures. Human figures appeared small, secondary. We'd assumed they were some kind of agricultural metaphors. A fertility cult, perhaps.

But now, deeper into the tunnel than we’d been before, we saw panels that were likely even older.

Crude and weathered nearly smooth, they showed human figures fleeing from what appeared to be radiating lines. Later scenes depicted the same root-like patterns, but with human figures positioned differently. Not fleeing anymore. They were being placed.

These were instructions.

The middle panels showed construction. Human figures carving channels—the same channels we'd been walking through. Others carrying blocks of stone marked with a distinctive pattern.

In the deepest chambers, we found where the channels terminated. Circular openings in the floor, worn smooth. Through gaps in accumulated debris, we saw living root tissue.

The channels hadn't been for drainage. They were feeding tubes.

I believe that whoever built this temple had built their entire temple complex as a delivery system. They turned this organism into a controlled method of execution.

For centuries, they'd likely fed it condemned prisoners, enemies, or perhaps volunteers. Maintained it. Managed it.

When their civilization collapsed, the maintenance ended. The organism remained, its purpose unchanged.

Even now, it waited at the terminus of those ancient channels for the next offering to descend.

We located Chen's secondary observation post by accident—Alison's foot caught on a guy-line still anchored in the undergrowth. The site was two hundred meters north of the main camp, a minimal setup that told a story of growing desperation.

Unlike the first camp, here, things were in disarray. Scattered notebooks showed water damage and what looked like burn marks. A field microscope sat uncovered, its lenses clouded with fungal growth. But it was Chen's final notes that gave us the most information.

Day 17: "The sound is constant now. All directions. Team reports inability to sleep. Rodriguez says it sounds like laughter. It obviously doesn’t—but knowing that isn’t helping."

Day 18: "Miller's incident catastrophic. Rhizomes breached tent floor overnight. Found him wrapped to the waist. Growth followed thermal gradient from sleeping bag. Took two hours to cut free."

Her final entry, scrawled with deteriorating control:

"Cannot risk direct escape through jungle. Trigger density measured at 15-20 per square meter. Running guarantees entanglement. DO NOT RUN THROUGH THE GROWTH. The faster you move, the more triggers activate."

That wet creaking—we'd been hearing it since arrival, dismissing it as settling wood or thermal expansion. But Chen's notes made us listen differently. The sound came in waves, rhythmic, almost respiratory.

It was the organism's voice.

Millions of cells undergoing rapid pressure changes created audible stress in the tissue. Like hearing a tree grow, but compressed from years into seconds.

The mechanism was simple. As water rushed into expanding cells, internal pressure could exceed 10 atmospheres. Multiply that by billions of cells extending simultaneously, and the collective groan became audible.

I recalled one legend, not unlike this one. One in which a man-eating tree was said to make sounds of its own, ones that sounded in the local language like “I see you.”

It didn’t seem so fanciful now.

But Madagascar was half a world away. Unless...

Well. No point in speculation.

The sound intensified that night. When we walked the perimeter, waves of creaking followed our path. The organism was mobilizing, redistributing resources toward our heat signatures. The louder it grew, the faster it approached.

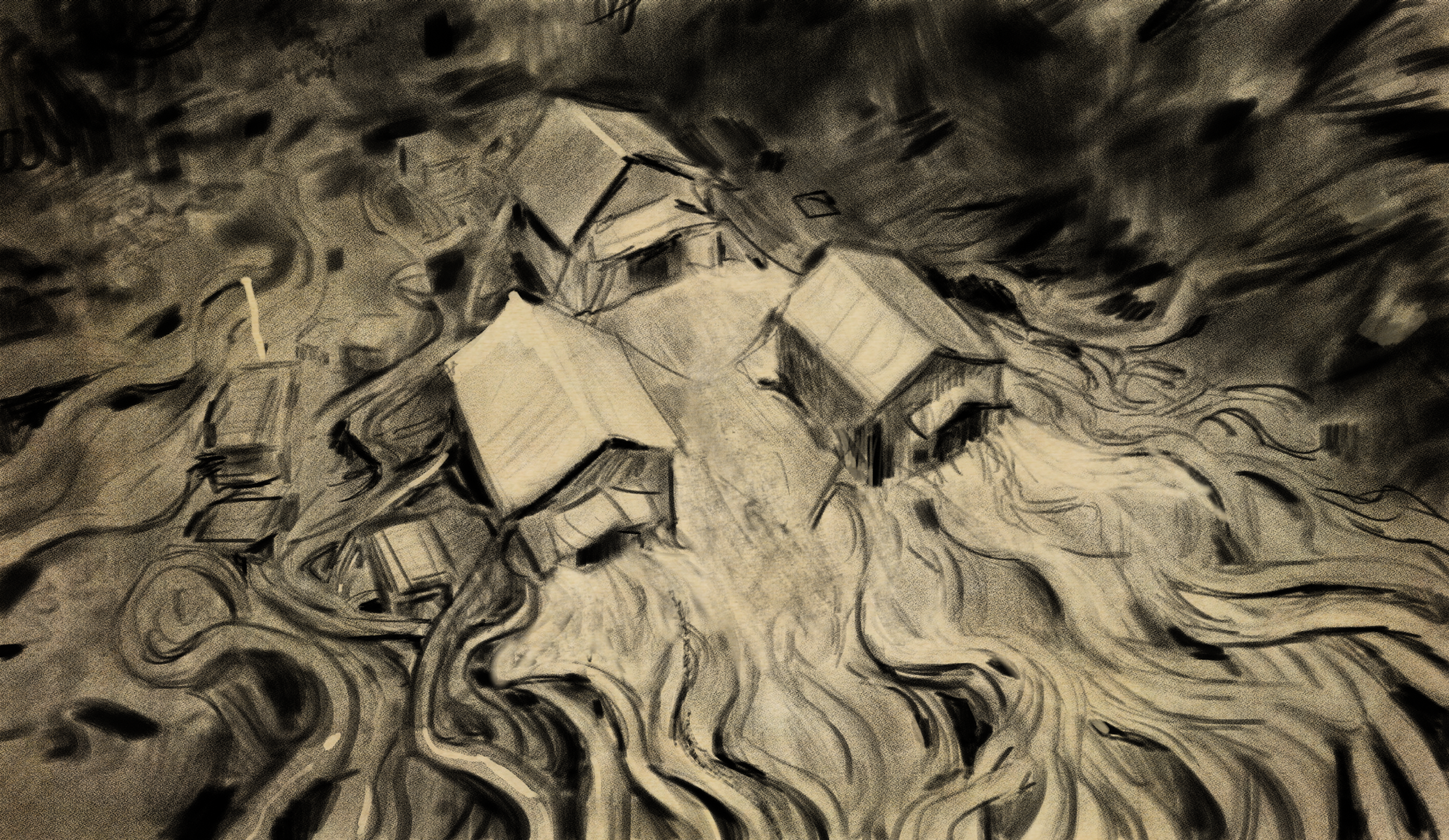

By our sixth day, the situation had become critical. The clearing had shrunk to eight meters across. Equipment at the periphery vanished beneath growth overnight. The sound was now constant—a wet, organic thunder that made sleep impossible.

That night, Alison woke us with a strangled cry. Rhizomes had breached her tent floor, likely following the CO2 plume from her breath. They'd wound around her ankle and wrist, not constricting but growing with inexorable patience.

In what was perhaps the most viscerally disturbing part of all of this, the plant tissue was warm to the touch.

We weren't just standing on soil anymore—we were centered on a primed digestive system, waiting for us to stop moving long enough to be processed.

And now, the wet creaking had taken on a strained quality, punctuated by occasional sharp cracks—like ice beginning to fracture.

By dawn, we noticed swellings emerging throughout the colony, pushing up through the soil like buried fists. By midday, these had developed into distinctive pods, their surfaces taut and segmented into precise geometric sections.

Marcus knelt beside one of the larger specimens, measuring roughly 30 centimeters across. The surface showed unusual strain patterns—minute cracks forming along the segment boundaries. I was collecting tissue samples when the first one detonated.

The pop was sharp, explosive, perhaps twenty meters to our north. Then nothing for several minutes. Another crack, this time from the east. Through binoculars, I caught the aftermath of a third—fragments scattered in a radial pattern, too fast to track individual trajectories.

The mechanism became clear through examination of a partially developed pod. The same hydraulic system that powered the trap contractions was building pressure within rigid-walled compartments. Inside, I found clusters of small, dense structures—vegetative propagules, little more than pre-formed clones wrapped in protective tissue. Like the bulbils some lilies use to reproduce, but increased in effectiveness through hydraulic pressure.

The process was elegant in its simplicity: water pumped in, but the lignified walls wouldn't expand. Something like Hura crepitans—the sandbox tree—but instead of months of passive drying creating tension, this was active pressurization. When pressure exceeded structural limits, the pod would rupture, launching its cargo of propagules in all directions.

By late afternoon, the pops came every few minutes. Marcus mapped each sound—older growth zones were dehiscing first, the wave of explosions working steadily inward toward our position. Through it all, that wet creaking continued, but strained now, like overtightened cables.

The entire organism was transforming itself into hundreds of botanical grenades.

The decision was straightforward. Fire was our only option.

We used our remaining fuel to create ignition points around the colony's perimeter. The dry season had left the outer growth desiccated, and flames spread quickly through tissue designed for fluid transport.

The sound as it burned was unlike anything I'd encountered—the wet creaking became a sustained rush as superheated water vapor escaped from millions of cells. Pods ruptured in the heat, but the updraft carried most propagules into temperatures that destroyed them instantly.

We retreated through the temple as the fire spread. Behind us, four hectares burned steadily. The sound of cellular rupture—that rushing release of hydraulic pressure—gradually faded as we gained distance.

By the time we reached safe ground, smoke rose in a thick column visible for kilometers. The fire would burn through the night, consuming decades of growth in hours.

Three days later, we returned to document the devastation. The surface destruction appeared complete—blackened earth, carbonized stems. The feeding depressions were now bowls of ash.

But in some places, pale shoots pushed through the blackened soil. The rhizome network had survived at depth, probably insulated by soil that never exceeded lethal temperatures. The organism would regenerate, perhaps taking decades to reach its former extent. But it would return.

We never found Dr. Chen or the rest of her team. The skull we discovered was too degraded for field identification. Perhaps they escaped through the temple as we did. Perhaps they made it to the surrounding villages. Or perhaps... Well. The feeding depressions were numerous. We recorded what we could at the time.

For now, I recommend continual monitoring, and perhaps eventual controlled burns to prevent dispersal.

Even now, somewhere in that valley, it grows. Patient as stone. It has outlasted the civilization that tried to appease it. It will outlast myself.

In the next decades, when new pods begin to swell, the only ones who will remember are the ones who never forgot in the first place.

The ground, it would seem, is still hungry.

Watch the video here:

Comments