Toothwedge

CW: Insects, grubs/maggots, icky parasitic vibes, body/insect horror

(look man, they're just gross!)

The toothwedge is a creature that can be found nestled in the jaws of large scavenging creatures across the known world. Each forming a unique shape, molded to the mouths of their carnivorous hosts, they benefit their hosts by keeping teeth healthy and protecting gums.

.

Toothwedges can be found between the teeth of large carnivorous creatures, particularly those that eat carrion, and have space between their teeth to support their shape. Adult females vary in size, growing to and forming their shape to match the shape of the teeth they live between. Most don't grow larger than a inch or two across the shell, but some very large exceptions have been documented. With a thick, chitinous shell, a mobile neck and two long arms, they can be found facing the inside of the mouth, wedged between teeth.

The toothwedge's luck-based reproduction process means that despite thousands of eggs being deposited by each male toothwedge, there are not so many that they would become a problem for hosts. Reaching adulthood is a rarity for most toothwedges, and they rely on their long lifespans allowing for them to make up for entirely lost clutches and play against luck.

Illustration shows a female and male toothwedge.

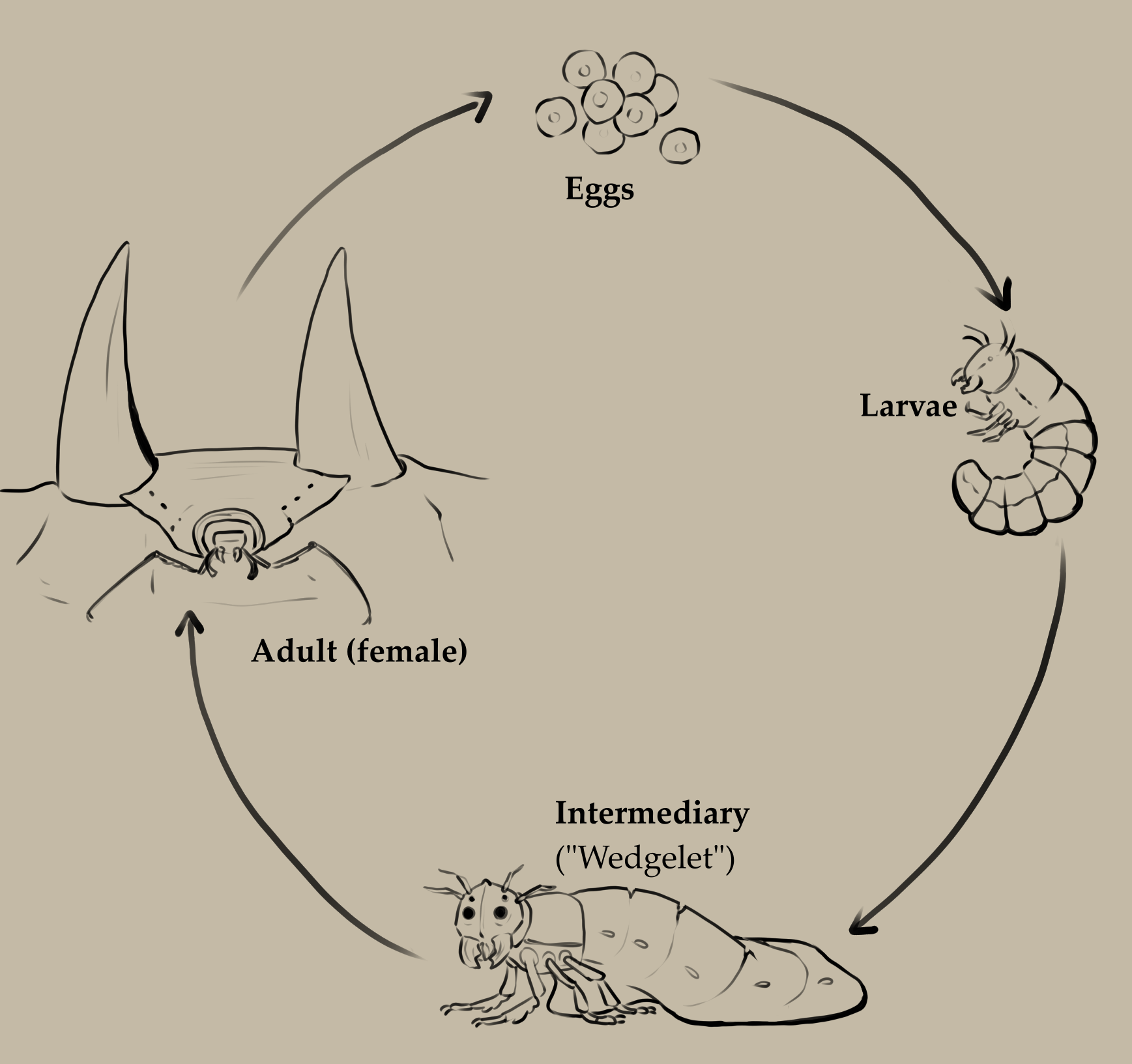

Larvae

Hatched from rotting meat, toothwedges begin their lives as tiny little maggot-like creatures. With small legs at the front of their body, they are able to drag themselves around the carcass that they hatch from, and can move around the mouths of their hosts. At this stage in their lives, they have simple eyes that detect light and dark, allowing them to navigate their surroundings. They also sport fine hair-like sensory organs that allow them to detect food, as well as pheromones produced by other toothwedges.

At this stage of life, the goal is to eat, grow, and if luck would have it, find itself a mouth to nestle into. Even if the grub happens to find its way into the mouth of a large carnivore, it is likely to be swallowed. If lucky enough to be flicked into the mouth during feeding, the grub will nestle itself into the space between the gums and the teeth. Only mere millimetres in length, grubs are so small they go entirely unnoticed.

Intermediary

During the intermediary stage of their life cycle, the female toothwedge is affectionately called a "wedgelet" by researchers. At this stage, the body shortens into a soft, tick-like, wedge shape that is disproportionate to the rest of her body. The toothwedge begins to take on a little of its signature blue-black sheen at this stage. Now too big to hide effectively in the gum space they have occupied previously, she will begin looking for a place to settle into adulthood, taking up permanent residency of a chosen gap between the teeth. This is the most vulnerable time of her life; not yet resistant to sharp bones or dragonfire, many wedgelets die before they are able to harden into their adult form.

An intermediary male will not become a wedgelet, and instead hardens into a pupae, and usually falls from the mouth of the host without them noticing. The pupae will lay on the ground where they fall. If lucky enough not to be eaten, stood on or otherwise destroyed, he will develop into a fly-like adult.

Adulthood

As the toothwedge reaches true adulthood, it takes up one of two forms, depending on its gender. The female loses all but two of her legs, the remaining two extending outwards to become spindly tools for finding food. She will lose her eyes and sensory hairs. She produces pheromones, telling other toothwedges nearby to keep away from its spot, and to signal her location to males. Hardening into her final form, she will not change shape again, and will remain in her chosen place for the rest of her life, which can last up to thirty years. Her shell is an iridescent blue-black, similar to the coloration of a crow or beetle.

Adult females always face the inside of their host's mouth. They can subsist almost entirely off of saliva, filtering food particles out of the moisture slowly over time. Their two remaining legs are almost always tucked up under the thorax, the entire creature remaining motionless for the most part. During the host's sleep, the toothwedge may explore its surroundings, gently tapping and investigating for food particles it can bring in with its long arms.

When males mature and hatch from their pupae, they become fly-like. They grow stronger legs, and develop large eyes specially designed for one thing: to detect the reflective blue sheen of an adult female. Perhaps the most obvious change in male anatomy is the large pouches that a male carries under his abdomen. These pouches are for carrying and fertilising eggs. Finally, and most importantly, a male will develop wings, allowing him to leave his host mouth and find a female.

Reproduction

Males have the difficult of locating a mate, safely reaching her, and then escorting her eggs to a place to hatch. While the female produces pheromones strong enough for males to follow, getting into the mouth of the predator carrying her is a challenge. Many creatures will swat flying insects away from their face and won't willingly open their mouths to them, however many dragons are intelligent enough to understand the benefit that toothwedges have, and will allow males to fly into their jaws.

If the male is lucky enough to make his way into the host's mouth, he will seek out a female. Females will give up their unfertilized eggs to the male by piercing a pouch on his belly with her ovipositor, laying the eggs directly in place. He may visit many females in his trip into one host mouth, carrying away eggs from multiple mates. The eggs are automatically fertilised within the pouch. From here, the male makes his final trip, seeking out carrion to feed his young. If he finds a suitable supply of meat, he will burrow his way into the corpse, where he dies. The eggs hatch within his body, and eat their way out.

Diet and Symbiosis

Perhaps due to the scarity of conversation with dragons during the Second Age, especially the scarcity of conversations with dragons about what's between their teeth, toothwedges were long thought to be purely parasitic to their hosts.

Somewhere between research by rare, but enthusiastic entemologists, and conversations with dragons, it became understood that the relationship between predator and toothwedge is more complicated.

An adult female toothwedges' dexterous legs can reach a surprising distance. This keeps the nearby teeth immaculately clean. They also produce an oil from pores on their exoskeleton. This oil protects their shell and conveniently protects the nearby teeth from decay. They do not impose on the predator's ability to eat or bite, and if anything, their shells shield the nearby gum from being poked by sharp bones. When they die, they become loose within days, and are easily dropped out of the mouth or able to be flicked out by more intelligent predators.

While their benefit to their host is not a lifechanging or a requirement, most hosts are more than happy to allow them to remain.

Hosts

You can find toothwedges between the teeth of most large predators with teeth. Studies have shown that one in three wild wargs carry at least one toothwedge. Predators that eat carrion are much more likely to carry toothwedges. An exception to the tooth rule is seen in griffons, who rarely have a particularly lucky toothwedge found lodged at the back of the joint of the beak; though this is rare.

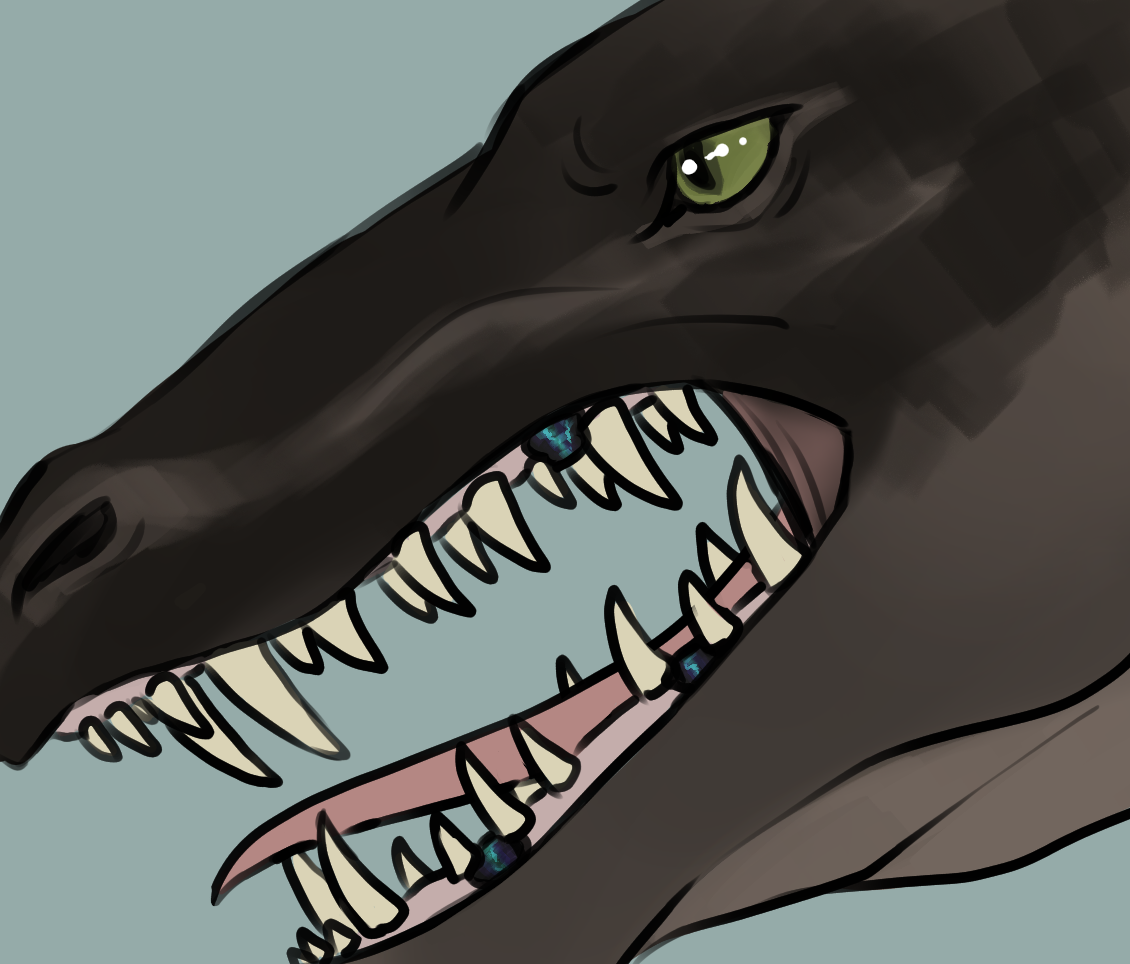

In Dragons

When most think of toothwedges, the first thing that comes to mind is rows of dragon teeth. Toothwedges and dragons go hand in hand, and most dragons are quite pleased to have rows of toothwedges between their fangs. Able to understand the benefits of the oil they produce, and also prone to an eye for shiny things, dragons are known to boast about their rows of shiny tooth ornaments. Many dragons will make a point to eat "ground meat" occasionally to renew their supply of shiny, living tooth-jewels, and allow males into their mouths to reproduce. When the insects die, dragons will often add them to their hoards of treasures, enjoining the glint that comes from their shiny black shells.

Uses

The chitin of the toothwedge is particularly tough, and holds its colour well. It is commonly made into jewelry, especially in cultures that particularly admire dragons such as Osmen. If ground finely enough for a long period of time, the powder can make a particularly beautiful, black, iridescent oil paint. The pigment doesn't dry down well if used in other forms, such as watercolour, and is very expensive.

Toothwedge oil is an extremely expensive product that has been in production for only the last century. Made by creating artificial teeth for female toothwedges to live on, labs are able to extract the oil produced by the insect to be used in toothpastes and mouth treatments to prevent tooth decay.

Male toothwedges and their unique egg pouches are highly sought after by alchemists. The fluid within the unburst egg pouches is designed to grow and nourish the eggs, and is used as an ingredient in preparations of anything from health potions to fertilisers.

This is a unique little critter and I enjoyed learning about them very much. The touch about dragons keeping them after death is equal parts just odd but also kind of adorable in a weird way, and that was a great touch that really grounded the relationship in an interesting fashion as well. The 'shiny living tooth-jewels' was equal parts imagery horror and weirdly adorable I simply felt so much conflict of emotions reading that! Well done certainly tucking this critter into my collection :)