The Monopolium Age

The monopolium age refers to the contemporary period where technologies based on magnetic monopoles are in use. Magnetic monopoles possess units of elementary magnetic charge: that is, a north magnetic charge or a south magnetic charge. An "atom" of a magnetic monopole with captured protons (and perhaps electrons as well) is called monopolium. The exact beginning of the age is disputed (some placing it as early as the discovery of monopolium in the Vulcanoid Belt in 2032), but the general consensus is that it began sometime in the mid-21st century. Examinations of monopolium in 2038 at Fermilab showed beyond a doubt that the Standard Model and General Relativity were incomplete. A Grand Unified Theory (GUT), and shortly afterwards Quantum Gravity, was worked out in the 2040s as a result.

The Monopolium Age saw the emergence of many new technologies, largely in virtue of portable room temperature fusion power generation, using 3He nuclei. Perhaps the most important of these are high-energy graviton technologies and the development of hyperfast interstellar travel.

Pronunciation

Unfortunately, many early magnetic monopole miners in the Vulcanoid Belt routinely mispronounced 'monopolium', so that even today, two ways of pronouncing the term exists. The proper way to say it is mon-o-po-li-um, but many M:Tron miners today (mis)pronounce it as meh-nop-o-lum. The latter faulty pronunciation likely emerged from those unfamiliar with the phrase 'magnetic monopole' and spoke 'monopolium' in light of how one pronounces 'monopoly' in English.

Monopolium Technologies

Nuclear Fusion Catalyzation

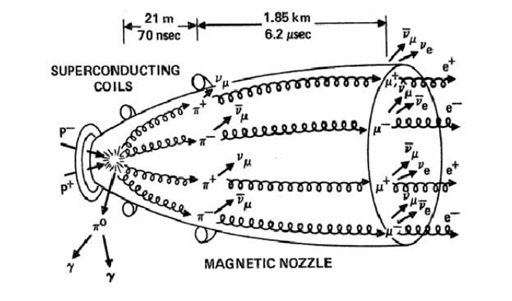

If two 3He nuclei approach too close to a magnetic monopole, they will overcome their Coulomb repulsion and fuse at room temperature, outgassing only alpha particles and protons. Thus, aneutronic and aphotonic cold fusion becomes possible with magnetic monopoles. Since the outgassed charged particles can induce electric currents to power equipment, this type of fusion technology is extremely energy efficient. The same technology can be used on a much grander scale for clean nuclear fusion rocketry, with an exhaust velocity of 6.8% of lightspeed. Monopoles are not expended or exhausted by this process, however only nuclei with an odd number of nucleons can undergo fusion catalyzation.

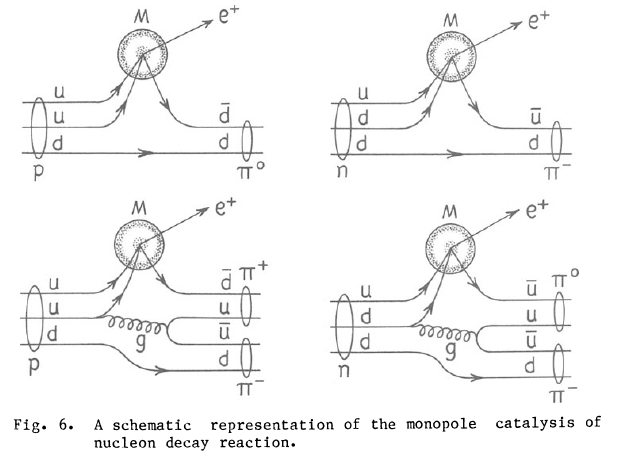

Nucleon Decay Catalyzation

GUT monopoles interact with normal matter by inducing nucleon decay (e.g., proton and neutron decay). The proton decays into a positron (e+) and various pions (π0 or π±). Neutral pions decay into two gamma rays (γγ), and since the kinetic energy of the pions is relativistic (0.94c) both photons will move in the direction of the neutral pion (relative to the apparatus). Charged pions (π±) usually decay into a muon and muon-antineutrino, which the muon promptly decays into an electron and an electron-antineutrino. Hence, GUT monopoles can be used (over and over) to catalyze nucleon decay to provide a near 100% mass to energy conversion power systems and rocket engines, exhaust velocity 94% of lightspeed. As a bonus: this is all without needing to store extremely hazardous and expensive antimatter!

To avoid complications with nuclear fusion catalyzation and the Pauli-exclusion principle, even numbered (or bosonic) nuclei are preferred in technological uses of nucleon decay (e.g., 132Xe or Xenon-132 for nucleon decay rocket engines). These nuclei do not interact with a monopole's magnetic field, and will ignore the presence of captured protons by the monopole.

Graviton Technologies

With the development of quantum gravity in the study of high-energy graviton physics during the 2040s, various technologies emerged which could exploit the nonlinear features of gravity on a small scale, in virtue of high-energy gravitons produced by GUT monopoles. Unlike the paragravity catapult envisioned by Robert L. Forward in 1963, high-energy gravitons allow for the creation of handheld paragravity devices. The list below covers the most notable of these technologies.

Paragravity

Having 6.2 mg/m3 of monopoles allows one to generate a sufficient amount of high-energy gravitons to duplicate a comfortable one-g environment, for use in either microgravity environments (spaceships) or celestial environments (colonial arcologies on moons and planets). Paragravity is essential for most habitation beyond Earth, since the human body has a very small window of tolerance regarding gravity, for long-term health. Since such a small amount is required for Earth-like gravity generation, personal and vehicle paragravity belts are common. The small range of such devices relative to that of Earth's radius and the density of the monopolium compared to that of Earth's density helps to reduce the bulk quantity of monopolium required (by 23 orders of magnitude), especially since the high density increases the presence of nonlinear interactions between gravitons. However, all such devices obey conservation of momentum, and thus cannot be used to generate free kinetic energy.

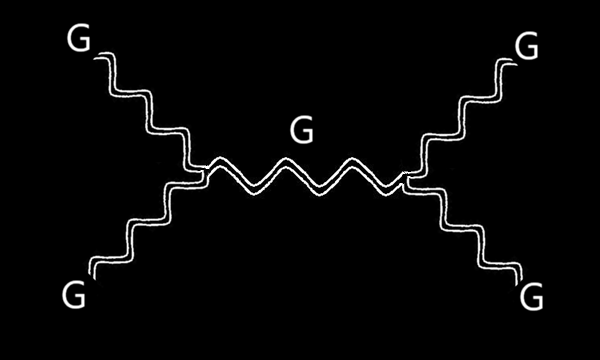

Stressor Beams

An extension of paragravity technology is the production of a beam of high-energy gravitons that induces intense oscillations in the curvature of spacetime. That is, a beam that induces gravitational stress on anything entering it. Such high frequency spacetime curvature oscillations (near the Planck scale) can induce severe damage to objects (much like acoustic vibrations), and every object is affected equally in virtue of the equivalence principle of General Relativity (which quantum gravity upholds). Such beams drop off at 1/r², thus with a beam divergence in kind with that of flashlights. There is no known method by which to generate a gravitational analogue of a laser at this time. Since gravity is nonlinear, stressor beams do interact with each other, unlike the linear dynamics that obtains for electromagnetic fields.

Hyperfast Interstellar Travel

Main Article: Riftgates

Among the predictions of quantum gravity in the 2040s, was father-than-light or hyperfast travel. With the development of riftgates, rapid interstellar travel became a reality in the late 21st century.

Physics of Monopolium

Unlike elementary particles (e.g., electrons), magnetic monopoles are not excitations of a "monopole" quantum field. Rather, they are topological solitons, which are localized regions of spacetime where a higher symmetry between fundamental forces remains compared to the rest of the universe. So, a GUT-scale magnetic monopole has a core region where the strong nuclear and electroweak forces are still unified. So during the Big Bang when the strong force split off from the electroweak force, the universe underwent a "phase transition" similar to how water becomes ice. Magnetic monopoles are defects in the "freezing out" of the universe (e.g., "cracks" in the "ice"). It is for this reason and that magnetic charge must be conserved, that magnetic monopoles will never undergo radioactive decay: they are stable over astronomical timescales.

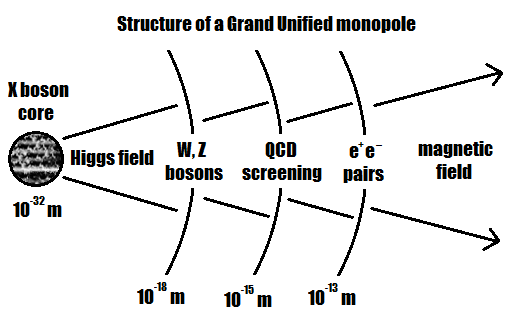

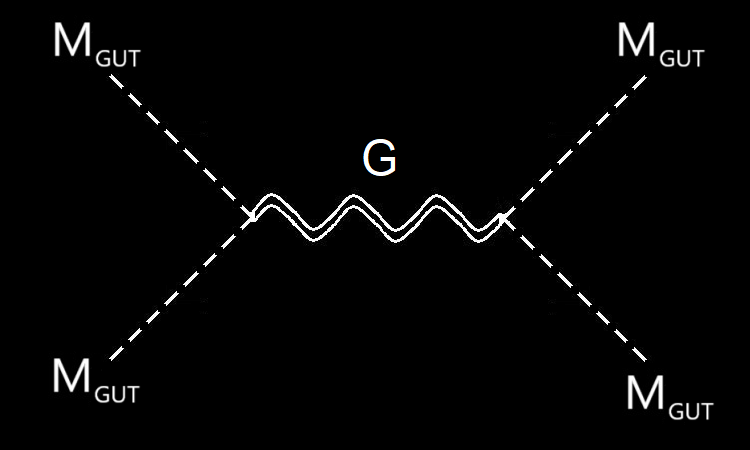

There is only one known type of magnetic monopoles, corresponding to the only first-order symmetry breaking event that took place during the Big Bang: GUT monopoles corresponding to the Grand Unified Scale at MX ≈ 1016 GeV (far above the Electroweak Scale, a second-order symmetry breaking event, where MW ≈ 102 GeV). Magnetic monopoles have a core of magnetic energy ~10-32 m radius. It is important to note that all monopoles have a rather complex structure outside of the core. Within a radius 10-18 m, magnetic charges are anti-screened or vanish and monopoles enter a bound state with one another in virtue of the Higgs Field post-electroweak symmetry breaking (see the diagram below of a monopole's structure). Beyond a radius of ~10-13 m monopoles behave like elementary particles: mere magnetic monopoles. The mass of a magnetic monopole is 1.03 x 1018 GeV, only 12 times less than Planck Mass (MP ≈ 1.22 x 1019 GeV or 22 micrograms).

Atomic Monopolium

In virtue of the dipole magnetic moment of elementary particles, some can couple with the magnetic charge of a monopole, and be captured into a bound state analogous to how atomic nuclei can capture electrons to form atoms. Unfortunately, unstable particles like neutrons are not held with sufficient binding energies by a magnetic monopole to make them no longer radioactive. A free neutron undergoes β- decay releasing 782 keV, far more than the binding energy of 10.36 keV. Thus, remaining bound to a magnetic monopole is not energetically favorable for neutrons. Electrons (nor positrons) can be captured by a solitary magnetic monopole into bound states either. This is due to the Schrödinger equation correctly predicting that an electron or positron will always have a repulsive centrifugal force in the presence of magnetic charges (in other words: monopolium is a superinsulator).

Protons however are not only stable around monopoles but they are relatively immune to nuclear fusion catalyzation, since an early step of proton—proton fusion requires a rare intervention by the Weak Force (something a monopole cannot assist with). With a 1s shell binding energy to GUT monopoles of 15.1 keV, monopolium can be extremely dense due to the 1s shell's radius of ~48 fermis. This distance is also far away enough from the monopole to avoid proton decay. However, with the presence of protons at a nuclear distance from the monopole, electrons can be captured at energies such as what happens inside of a hydrogen or helium atom. Now, there is no 2s shell for protons bound to a monopole, since the net angular forces will be repulsive. Hence the maximum number of protons a monopole can capture is merely two, of opposite spin, to fill the proton's only s shell. More than two electrons can be bound to a monopole-proton system, with the whole system (monopole-protons-electrons) behaving as negatively charged ions.

Monopolium Shells

Ionizing Radiation

Magnetic monopoles are highly ionizing (i.e., can strip electrons from atoms, with those electrons producing X-rays as secondary radiation) if encountered as free particles. Thus, they can be quite dangerous for both biological and electronic entities.

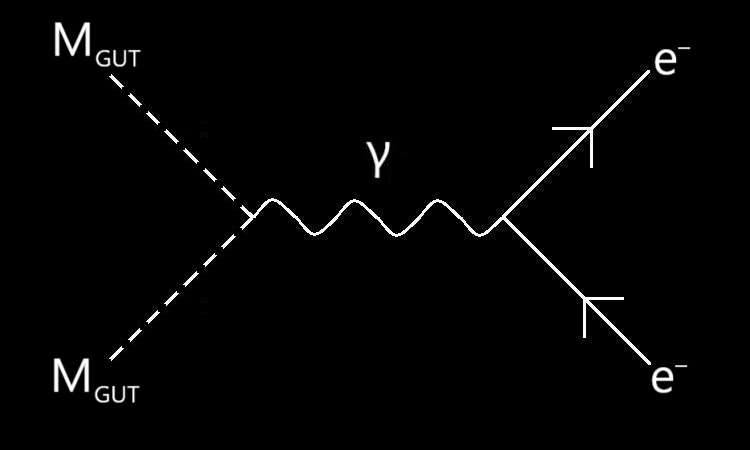

Gravitational Radiation: Gravitons

Monopoles are so close to Planck Mass that their excitations produce quantum gravitational effects. It was in 2038 at Fermilab that the graviton (the spin-2 boson, G, responsible for gravitational interactions) was finally discovered. GUT-scale monopoles possess a mutual gravitational interaction some 1042 times stronger than the gravitational interaction between two electrons, and have an electromagnetic interaction 4692 times stronger than that between electrons. So, since the electromagnetic force is 1037 times stronger than gravitation, the high energy gravitons produced by a system of magnetic monopoles end up being several times more potent than photons produced by that same system. These high frequency gravitons correspond to extremely strong disturbances in spacetime curvature. If monopoles were less massive by even a few orders of magnitude, the emission of photons would dominate and gravitons would remain unknown to us.

Since ordinary matter (protons, neutrons, and electrons) is very weakly coupled with the gravitational interaction, monopolium is much better suited for graviton detection devices. Since monopolium is involved with both gravitation and electromagnetism, conversions between the energies of those two fundamental interactions is accomplished in a practical manner with monopolium. That is, if a magnetic monopole is struck by a graviton, there is a good chance that a photon will be emitted, which can then be detected by ordinary matter. If GUT-scale monopoles were much more massive than they are, graviton emissions would dominate and graviton—photon conversion techniques would be impractical.

Investigations into gravitons, first at Fermilab in 2038, led to the discovery of not only a slew of quantum gravitational phenomena, but the specifics of the nonlinear nature of gravity in a quantum mechanical way. Some of these nonlinear quantum corrections includes the positing of paradoxical effects among high-energy gravitons: sometimes repulsive gravitational fields appear in highly warped spacetimes. The quantum gravity revolution began in 2038 at Fermilab, as various ad hoc corrections to the Einstein Field Equations had to be made to account for these phenomena, resulting in a proper theory of quantum gravity during the 2040s.

Natural Occurrence of Monopolium

While there are two (potential) sources of magnetic monopoles, only one has been confirmed: monopolium ore on vulcanic worlds or vulcanic asteroids that attracted monopoles made during the Big Bang. Now, just as red dwarfs (type-M stars) attract more magnetic monopoles to their planets than type-G or type-K stars, in virtue of their stronger magnetic fields, it is expected that planets around neutron stars are even richer in monopolium ore. However, humanity has not yet encountered a neutron star close enough to Sol to examine.

Since relic monopoles exist from the Big Bang, it is expected that cosmic strings exist and their decay involves the emission of both gravitational waves and magnetic monopoles, but none have been found thus far.

Monopolium Ore

Among both vulcanoids and vulcanic planets, bulk monopolium is never found in a pure state: it is usually intermixed with ferromagnetic elements like iron and nickel (usually all three mixed together). It is the close promixity of iron-nickel to a star's magnetic field that magnetizes the iron-nickel, which draws in monopolium from the stellar medium. This is a negative feedback loop, for as the magnetized iron-nickel attracts more monopolium, the magnetic field is "poisoned" by that very same monopolium. It is why both vulcanoids and the surfaces of vulcanic planets have very weak magnetic fields overall. Monopolium ore appears like any iron-nickel deposit, except that there is the presence of small translucent nodules, the more monopolium rich parts of the iron-nickel ore. Monopolium has a low plasma frequency, and so appears transparent when not mixed with iron-nickel material.

A neutron star is the remnant of a supernova, a body composed of neutron degenerate matter (i.e., neutronium), speculated to have quark degenerate matter in their cores. For quite a time after the supernova that birthed it, a neutron star has a very powerful magnetic field. It is this field that is speculated to be powerful enough to attract magnetic monopoles to enrich their planets with monopolium ore. Sadly, the closest known neutron star to Earth is some 400 light-years away. However, it is quite possible that there are closer neutron stars: not only is the galactic density of neutron stars one per 500 stars (so one every 34.2 light-years), but neutron stars emit energies in narrow cones, and are generally not radiating in the visible light part of the spectrum anyway. Searches are underway by many corporations, including M:Tron.

Monopolium Ore Refinement

Since pure monopolium is a prerequisite for its technological use, melting monopolium ore is essential. Since the melting point of the various types of monopolium is well over that for all the elements in the periodic table, one can "drain off" the now liquid iron and nickel and be in possession of purified monopolium. Initially, the liberated monopolium exudes from the molten ore as microscopic dust particles, collected by a electromagnetic dust trap (usually coated with tungsten for its high melting point). However, since purified monopolium dust approches the density of a neutron star (>1018 kg/m3), it is suspended as a gas in a magnetic bottle to reduce the density for transport.

Cosmic Strings

Cosmic strings are a proposed relic from the Big Bang, a topological defect or soliton like magnetic monopoles are. Magnetic monopoles can be thought of as zero-dimensional defects, and cosmic strings are one-dimensional defects: a very thin object (~10-32 m radius) under immense tension, potentially spanning the size of the observable universe. Their proposed mass density is equal to their tension, some 1021 kg per meter of length. If a cosmic string intersects another, they break and form a slew of magnetic monopoles, gravitational waves, and closed loop cosmic strings. The closed loops then continue to decay gravitationally, over astronomical timescales.

Before the discovery of the Vulcanoid Belt and its plentiful magnetic monopoles, it was speculated that the cosmic occurance of relic cosmic strings from the Big Bang where around one per billion cubic light-years. However, the discovery of the Vulcanoid Belt and Vulcanic planets forced a revisal of those estimates such that many more should exist, despite none having been found so far. Cosmic strings are very hard to locate at a distance, since their tension and mass density cancel out gravitationally (tension is also negative pressure, a component to be calculated in the stress-energy tensor of General Relativity), they exert no gravitational forces on nearby objects despite their immense mass. However, light passing near a cosmic string will encounter a "conical deficit": the area around a cosmic string is less than 360° and will bend light, creating a double image of objects behind a cosmic string.

If a cosmic string is ever found, even a meter long cosmic string would satisfy the need for magnetic monopoles by humanity for eons.

References

General Physics

Original Usenet Physics FAQThe Physics Stack Exchange

Atomic Rockets by Winchell Chung

Forward Paragravity (1963)

Forward Indistinguishable from Magic (1998)

Magnetic Monopoles

Short Primer on Magnetic Monopoles (Free 2017)Good Primer on Magnetic Monopoles (1984)

Extensive Research on Magnetic Monopoles (1983)

No Electron Bound States to Monopoles (1948)

Electron Bound States to Atomic Monopolium (1951)

Cosmic Strings

Number of Cosmic Strings (2014) / (Free Version)Monopolium-Rich

Sol: Vulcanoid BeltAlpha Centauri A-I: Vulcan

Proxima Centauri I: Ferrum

Proxima Centauri II: Lacus

Barnard's Star III: Mercutio

Barnard's Star IV: Tybalt

Wolf 359 I: Ares

Wolf 359 II: Boreas

Tau Ceti I: Hephaestus

Kruger 60 A-I: Nacluv

Kruger 60 A-II: Latsyrc

Related Articles

M:Tron CorporationColonial Arcologies

Riftgates