Shemaz

The language of Shemaz is spoken by the majority of humans in the world of Salkur. It has two dialects: Kirden and Birren.

/y/ > /vw/ > /l/ > /m/ > /n/ > /r/ > /z, zh/ > /f, s, sh/ > /kh/ > /gh/ > /ch/ > /b, d, g/ > /p, t, k/

For any consonant cluster in a coda, a given consonant cannot be preceded by a consonant that comes later in the heirarchy, nor proceded by one that comes before it. The same applies to a consonant cluster in an onset, but with the heirarchy reversed.any consonant followed by itself or another consonant in its level of the heirarchy

/p/, /t/, or /k/ followed by /b/, /d/, or /g/

/gh/ and /kh/ after each other in either order

/gh/ followed by /f/, in an onset

/s/ followed by /z/

/sh/ followed by /zh/

/r/ followed by /n/ or /m/, in an onset

/y/ followed by /ch/ or /vw/, in a coda

Higher numbers continue as such, with a higher level being increased at the square of the previous, and being assigned the name of fliinsaa, followed by the number of its higher level.

[ʒ] becomes the voiced postalveolar fricative [dʒ]

[ɛ] becomes the mid front unrounded vowel [e̞]

[ɞ] becomes the mid central vowel [ə]

[a] becomes the open central unrounded vowel [ä]

The noun class Thing That Helps is replaced with Thing That is Useful.

The noun class Thing That Looks Bad is replaced with Thing That is Wasteful.

The Past tense is split into a Recent Past and Far Past tense. They are realized as se____ and suh____ (eg. sepmlt and suhpmlt), respectively.

The Iterative Aspect is added, indicating that an action is repeated, often connoting an improvement or change attempted in successive instances. It is realized as _ee___ (eg. peemlt).

The Hypothetical Mood is added, which indicates that something might happen (I coulddo this / have done this. It is realized through the preposition rore (eg. rore pmlt).

All images created by Flyerstitch

Phonetics

The following are the sounds used in Shemaz. Bracketed sounds are IPA classifications, and any letters between slashes are how they will be anglicized. For more information on these sounds and how they're made, check out https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IPA_consonant_chart_with_audio and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IPA_vowel_chart_with_audio.Consonants

Bolded sounds are voicedBilabial

Labiodental

Alveolar

Postalveolar

Palatal

Velar

Nasal

[m]

[n]

Plosive

[p][b]

[t][d]

[k][g]

Affricate

[tʃ]/ch/

Fricative

[f]

[s][z]

[ʃ]/sh/[ʒ]/zh/

[x]/kh/[ɣ]/gh/

Approximant

[ʋ]/vw/

[j]/y/

Trill

[r]

Lateral Approximant

[l]

Vowels

Bolded sounds are unroundedFront

Near-front

Central

Near-back

Back

Close

[i]/ii/

Near-close

[ɪ]/i/

[ʊ]/u/

Close-mid

[e]/ee/

[o]/uu/

Open-mid

[ɛ]/e/

[ɞ]/uh/

[ʌ]/a/

Open

[a]/aa/

Phonology

Syllables

Shemaz uses at most two consonants in a cluster in a syllable, or a max of CCVCC. This can be expanded to a mazimum of four consonants if two syllables with two consonants in the clusters facing each other are put together (VCC + CCV = VCCCCV). There are two exceptions to this rule: the onset consonant clusters /shmy/ and /rlvw/. The consonants in clusters can be arranged in the following heirarchy:/y/ > /vw/ > /l/ > /m/ > /n/ > /r/ > /z, zh/ > /f, s, sh/ > /kh/ > /gh/ > /ch/ > /b, d, g/ > /p, t, k/

For any consonant cluster in a coda, a given consonant cannot be preceded by a consonant that comes later in the heirarchy, nor proceded by one that comes before it. The same applies to a consonant cluster in an onset, but with the heirarchy reversed.

Phonotactics

In addition to the general rules layed out by the sonority heirarchy above, there are some more orderings of sounds which are forbidden in Shemaz. Assume for the following that a given ordering is for an onset and applies in reverse for a coda, unless stated otherwise.Vowels

All vowels can work as the nucleus of a syllable. As there are no diphthongs in Shemaz, if two vowels come sequentially after each other, as in the case of CV + VC, they are seperated with a glottal stop ([ʔ] or /'/). For example, /sha/ and /ez/ become /sha'ez/.Stress

Shemaz uses a phonemic stress system, meaning that all words have their own stress patterns that are not automatically determined by rules.Morphology

Noun Class

All nouns in Shemaz fall into six classes. Each class represents a level of respect required to show to it. They are, in descending order, humans, animals, things that help, things that look good, things that look bad, things that hinder or hurt. Things that help are items such as clothes, food, or reliable tools. Things that look good are items that areliked but don't provide any special assistance, such as flowers or decorations. Things that look bad are items that don't necessarily harm, but detract from one's positive mood, such as big holes in the ground or broken personal items. Things that hinder or hurt are things that actively do bad for someone, like injuries or spoiled food. If one wants to show extra respect or disrespect to something, they can raise or lower their noun class. The classes are all in realized through suffixes, as demonstrated with the word /kshe'akh/, meaning object, below:Class

kshe'akh

Human

kshe'akh

Animal

kshe'akhsaa

Thing That Helps

kshe'akhpu

Thing That Looks Good

kshe'akhchii

Thing That Looks Bad

kshe'akhluh

Thing That Hinders or Hurts

kshe'akhchu

Grammatical Number

There are five categories of number that can be encoded onto a word in Shemaz. They are single, multiple (few), multiple (many), none, and lack. Single refers to a single instance of the subject. None refers to exactly zero instances of the subject, whereas lack indicates to an absence of instance(s) of the subject that should be present. The difference between the few and many varieties of multiple is largely based on the relativity of quantities in the speaker's mind. The difference between most numbers is preffixual, with the exception of multiple (few), whose first syllable is reduplicated (placed again at the front of the word), as shown in the table below, with no root and with the example root /fuzh/, meaning tree:Number

_____

fuzh

Single

_____

fuzh

Multiple (Few)

__________

fuzhfuzh

Multiple (Many)

gluu_____

gluufuzh

None

zha_____

zhafuzh

Lack

ist_____

istfuzh

Noun Case

Nouns may act differently in Shemaz based on what roles they are playing in a sentence. The different cases that nouns may use are elaborated upon below.Morphosyntactic Alignment

The alignment of a noun refers to how it's treated in relation to its modifying verb. Shemaz uses Tripartite Alignment, which classifies the subject of an intransitive verb, the subject of a transitive verb, and the object of a transitive verb differently. An intransitive verb is one which only uses one noun, such as in the English sentence "I ran". In this case, 'I', being the subject of the intransitive verb, would be given the Intransitive Case. A transitive verb is one which uses two or more nouns, such as in the English sentence "I bought groceries". In this case, 'I' would be the subject of the transitive verb, as it is the one doing the action, thus it would be given the Ergative Case, while 'groceries' would be the object of the transitive verb, being the one that the verb is done to, and thus would be given the Accusative Case. There are no ambitransitive nouns, or nouns that can be used as both transitive and intransitive (as in the English cases of "I eat" compared to "I eat cereal") in Shemaz. For a word that might otherwise be ambitransitive, the missing object is replaced with /aalkshe'akh/ (something), /aalmzhiis/ (someone), or a similar equivalent.Genitive

The Genetive Case is used to indicate that one noun is possessed by another noun. This can be comparitive to the English 's, as in the case of Bob's trumpet, except that in Shemaz, the "trumpet" would be the word receiving the Genetive Case. The noun that is the possessor gains an adjectival status, and is realized in a similar manner to adjectives, as shown in the adjective section below.Instrumental

The Instrumental Case is used to indicate that the noun is being used as a tool to do an action through it. This can be demonstrated in English in the sentence "I dig a hole with a shovel". 'Shovel' here is an instrument, and in Shemaz would be given the Instrumental Case.Realization

Noun cases are realized in Shemaz through various adpositions, or words that directly surround the noun to give it meaning. They are showed in the chart below.Case

_____

Example

Intransitive

_____ muul

saal muul tita (I run)

Ergative and Accusative

(Subject) ayge (Object)

saak ayge pmuhm pmaltii (I eat food [lit. I food eat])

Genitive

(Possessor) _____ vwer

rab saal travw tii pmuhm vwer (My food)

Instrumental

khlii _____

saak ayge pmuhm pmuhltir khlii zhruun (I eat food with a utensil)

Verbs

Verbs in Shemaz have roots made of a set of four consonants. They do not carry over grammatical number from nouns. They do, however, agree with the classes assigned to their modifying nouns and also encode person, tense, aspect, and mood.Class

Verbs in Shemaz agree with noun class through infixes. These are affixes that go in the middle of the verb, between the second and fourth consonants of the roots. These infixes are a single vowel, as shown in the table below, with the root pmlt, meaning to eat.Class

____

pmlt

Human

__a__

pmalt

Animal

__aa__

pmaalt

Thing That Helps

__uu__

pmuult

Thing That Looks Good

__ii__

pmiilt

Thing That Looks Bad

__uh__

pmuhlt

Thing That Hinders or Hurts

__e__

pmelt

Person

Grammatical Person refers to the relation of the noun committing an action to the speaker. Shemaz has three persons: first person, second person, and third person. They are encoded on a verb as suffixes, as shown once again with the verb root pmlt below.Person

____

pmlt

First Person

____ir

pmltir

Second Person

____aar

pmltaar

Third Person

____ur

pmltur

Tense

Tense describes how an action occurs in relation to time. Shemaz has four tenses: past, present, near future, and far future. Tenses are marked with prefixes, as shown below.Tense

____

pmlt

Past

se____

sepmlt

Present

____

pmlt

Near Future

sa____

sapmlt

Far Future

suu____

suupmlt

Aspect

Aspect describes how an action extends over time. Shemaz has seven aspects. The Perfective Aspect describes an action as a whole (i.e. I did an action). The Stative Aspect describes an action as a state of being (i.e. I know this). The Progressive Aspect describes an ongoing event (i.e. I am doing an action). The Inceptive Aspect describes the beginning of an action (i.e. I am starting to do an action). The Terminative Aspect describes the ceasing of doing an action (i.e. I finished doing an action). The Inceptive and Terminative aspects both have Stative and Progressive versions. Aspects in Shemaz are realized with up to two infixes, the first being between the first and second consonants of the root and the second being between the third and fourth. They are realized as demonstrated below.Aspect

____

pmlt

Perfective

____

pmlt

Stative

_i___

pimlt

Progressive

_aa___

paamlt

Inceptive Stative

_i__uh_

pimluht

Inceptive Progressive

_aa__uh_

paamluht

Terminative Stative

_i__e_

pimlet

Terminative Progressive

_aa__e_

paamelt

Mood

Mood describes how an action described relates to reality. There are four moods in Shemaz. The Indicative Mood indicates a statement of facts or beliefs (This is true, I think this). The Subjunctive Mood indicates a possibility that something is true (I think that this true). The Conditional Mood indicates that something only happens as long as a condition is met (I would do this, if this were true). The Imperative Mood is used to give a command (Do this). The Imperative mood can apply to any Person. A verb's mood in Shemaz is realized through prepositions, as shown in the chart below.Mood

____

pmlt

Indicative

____

pmlt

Subjunctive

pzu ____

pzu pmlt

Conditional

ghalech ____

ghalech pmlt

Imperative

seelmaa ____

seelmaa pmlt

Infinitive

The Infinitive form of a verb is the basic use of a verb and is without person, tense, aspect, or modality. It is seen similarly in English with a verb conjoined with the word "to" (eg. eat vs. to eat). It is realized the the postposition vwud (eg. pmlt vwud).Adjectives

Any word in Shemaz can gain the property of being an adjective by being given the circumpositions rab and _ral, as such: rab _____ _ral. The blank in the second word changes based on what class the affected word belongs to, as shown in the chart below. For possessors of an object being given the genetive case, _ral becomes _ravw. There is no distinction for adjectives affecting different types of words in Shemaz, as with the adjective-adverb split present in English and many other languages.Class

____

pmlt

Human

rab ____ tral

rab pmlt tral

Animal

rab ____ sral

rab pmlt sral

Thing That Helps

rab ____ pral

rab pmlt pral

Thing That Looks Good

rab ____ chral

rab pmlt chral

Thing That Looks Bad

rab ____ gral

rab pmlt gral

Thing That Hinders or Hurts

rab ____ ghral

rab pmlt ghral

Word Order

As noted above, Shemaz uses Subject - Object - Verb ordering in clauses. In the case of an instrumentally cased object, the instrumental noun is placed after the verb. Adjectives are placed before whatever they are describing.Writing System

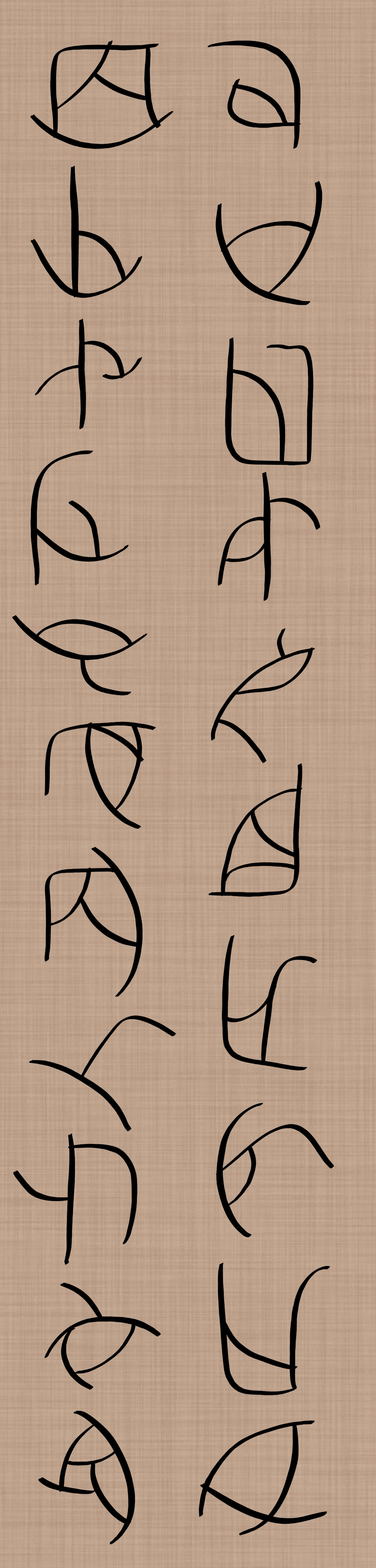

The written language of Shemaz is an abgad, meaning that consonants are represented by letters, while vowels take the role of punctuation around the letter. Unlike many abgads, the vowel markings in Shemaz are not optional, and must always be written. Shemaz is traditionally written with ink brushes on parchment, although later times have introduced otehr implements that can also be used to write. Shemaz is a language written from top to bottom, with the next coumn of text written to the right of the previous.The Alphabet

The consonants of Shemaz are as follows: sal, vwiil, kal, zhiil, fiil, ger, tal, ral, chiir, zuhk, diir, mal, nal, yal, khiir, ghal, pipaa, shu, biil, lal, aa'ii. In order, they correspond with the sounds s, vw, k, zh, f, g, t, r, ch, z, d, m, n, y, kh, gh, p, sh, b, and l. The last latter, aa'ii, makes no sound, but rather is a placeholder for vowel punctuation when a word requires vowels that can't be joined with consonants. The vowels of Shemaz are written along the middle line of the characters, inside whichever character they are joining. A joined letter says its vowel first, then whatever consonant sound it makes. The different vowel markings are the aayl (aa), the bi'i (i), the een (ee), the uhchii (uh), the ezh (e), the uku (u), the am (a), the iigh (ii), and the uuluu (uu).Uppercase

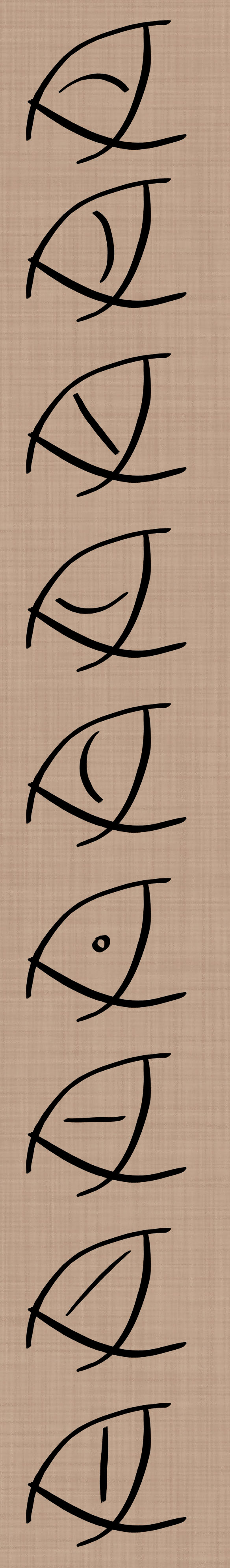

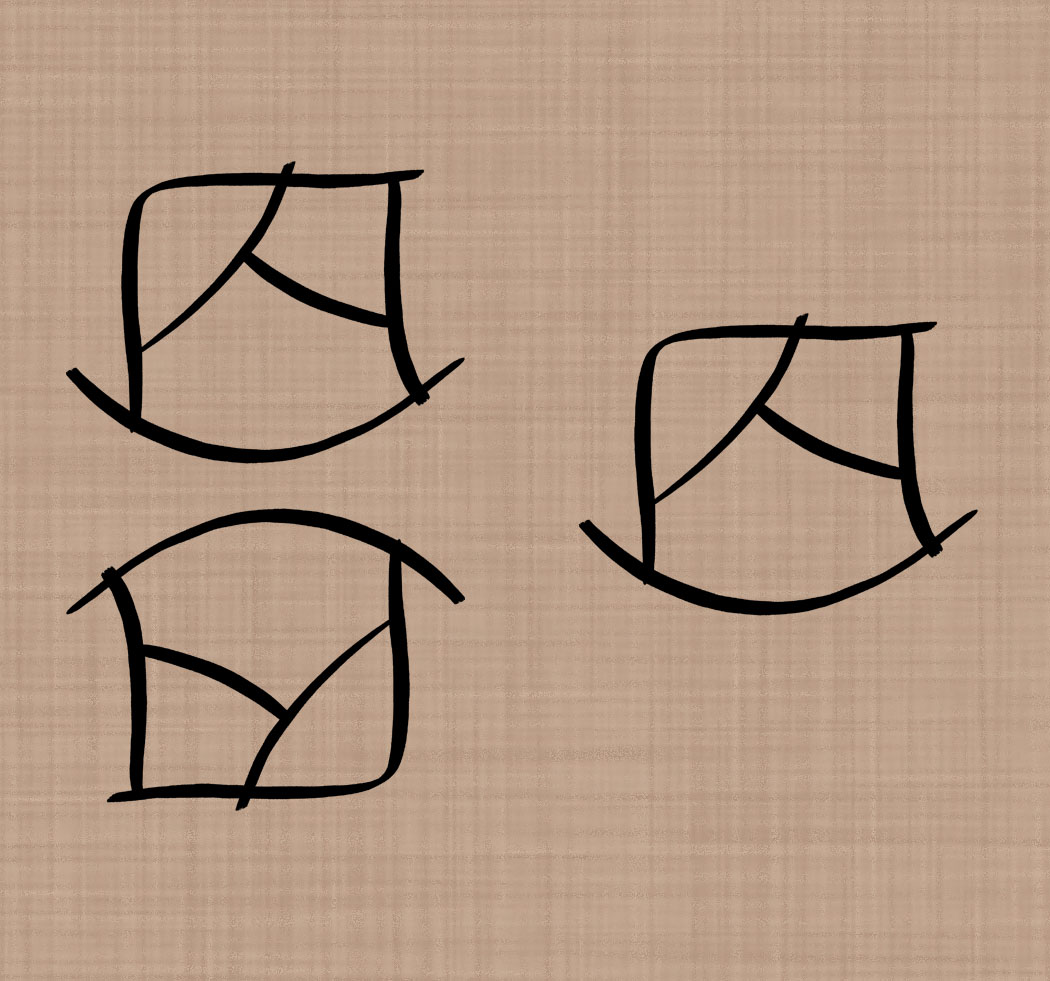

To show special honor to a word, any number of the letters, typically starting from the beginning and continuing in as far as desired, may be written with Uppercase. This is a process that simply involves moving the orginal letter higher and replicating it upside down underneath its original form. Below is shown the letter sal, in uppercase to the left, and not in uppercase to the right.Numbers

Numbers in Shemaz are split into bases of five with subbases of 2. This means that counting up from zero would go as follows: 0, 1, 1', 2, 2', 3, 3', 4, 4', 5, 5', where every number has a lower and higher form, up to 5' which becomes the next numeral place for the next set (=10). Numbers are written just as letters, going top to bottom and then left to right, with the first number being the smallest place and then later numbers being of higher places. All numbers are written onto the base number glyph, which alone would be zero, as shown in the top right in the diagram to the right. The lower form of every number is curved towards the opening, and the higher form is curved away. To make a number negative, a second stroke is affixed to the left side of the glyph opening. To the right are the numbers of Shemaz, in order, 1, 1', 2, 2', 3, 3', 4, 4', 5, 0, -1.

Cardinal Numbers

Numbers as themselves are treated as nouns and called cardinal numbers. Below are the cardinal number names in Shemaz.English Analog

Shemaz Number

Name

-1

-1

chutzuh

0

0

khaa

1

1

tzuh

2

1'

tzii

3

2

zhuhm

4

2'

zhiim

5

3

chuhl

6

3'

chiil

7

4

kruhn

8

4'

kriin

9

5

fluhn

10

10

fliin

11

11

tzuh fliin

100

100

fliinsaatzuh

10000

10000

fliinsaatzii

100000000

100000000

fliinsaazhuhm

Quantitative Numbers

Quantitative numbers are used as adjectives, and show how many of an object there are they are surrounded by the typical rab ____ _ral of adjectives, with the _ral taking the class of the word it is describing (eg. rab chuhl tral fuzhfuzh - three trees).Ordinal Numbers

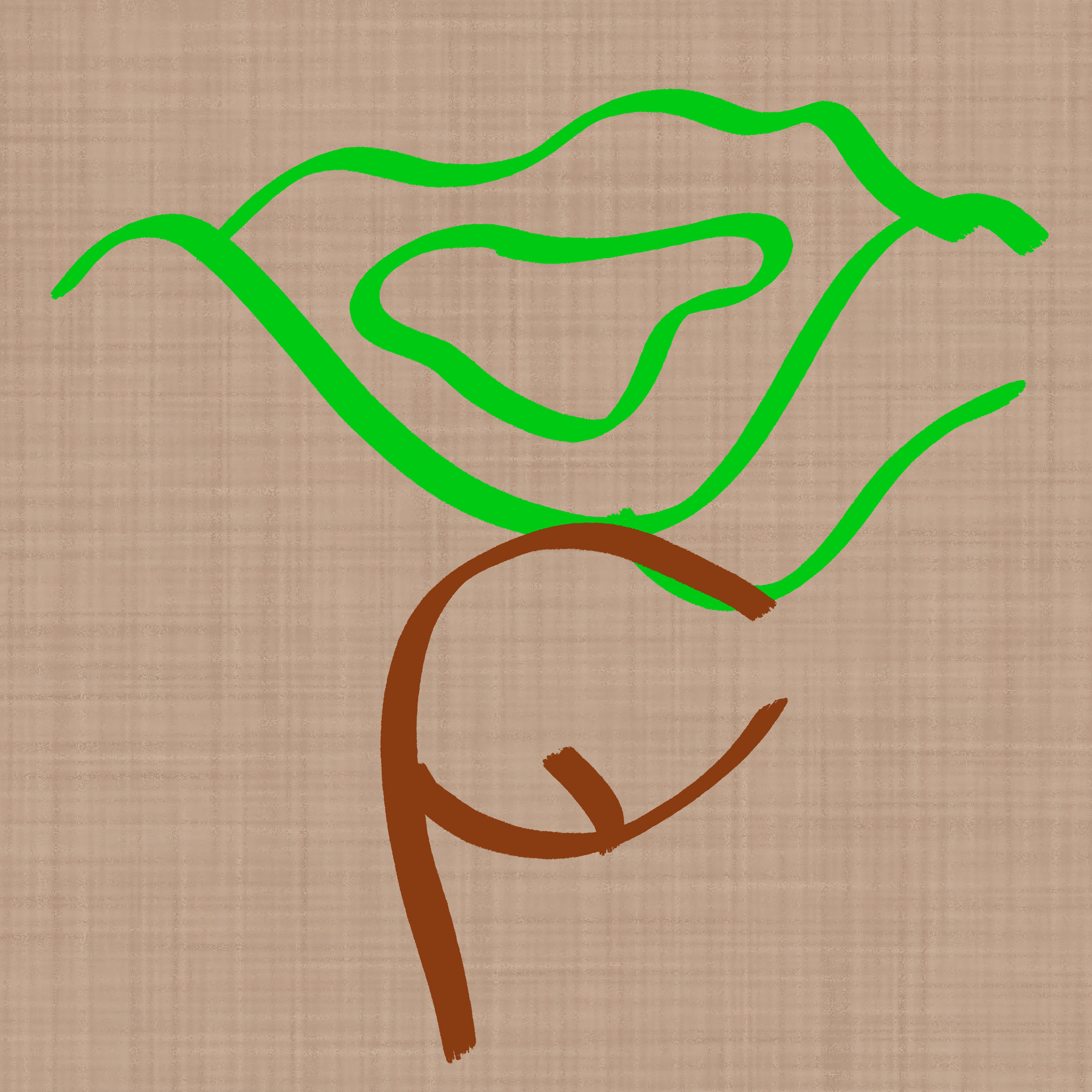

An ordinal number represents something as being the given instance in a sequence. In English, this is the transformation of a number like "five" to the term "fifth". They act similarly to quantitative numbers except that they given the word klaag after the _ral (eg. rab chuhl tral klaag fuzhfuzh - the third of a small multiple amount of trees).Artistic Type

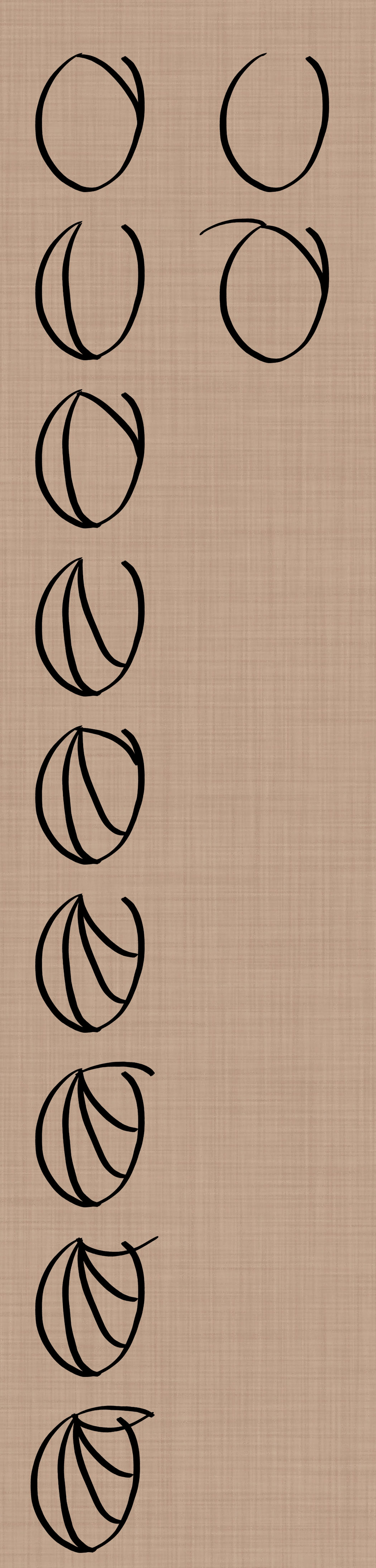

While all letters so far have been discussed in standard type, there also exists an artistic type for more creative pieces of writing. It involves three factors: the base, which is any letters being incorporated; the color; and the shape. The letters can be anything, but are usually a description or commentary on what they're depicting. The shape is a warping of the lines of the letters, while still making them identifyable, into the form of something else. Color is used to help the illustration.Birren Dialect

While all rules so far have been of the more common Kirden dialect of Shemaz, there are some changes made in the dialect spoken by the Birren people.Phonetics

Morphology

Dictionary

Common Phrases

rab laar tral klamuhn vwer - May your morning be good

shaa'iish - Greetings

rab rab laar tral salk vwer tral ekur - May you be respected for your life (often end of conversation)

shaa'iish - Greetings

rab rab laar tral salk vwer tral ekur - May you be respected for your life (often end of conversation)

Remove these ads. Join the Worldbuilders Guild

Comments