Monopolium

Page Back Under Construction (Update November 2025) |

|---|

An "atom" of a central magnetic monopole with captured protons and electrons is called monopolium (pronounced: mon-o-po-li-um). Magnetic monopoles are essential to all gravity control technologies and portable fusion power generators. To be specific, their uses range from providing one-g conditions in space colonies and spacecraft, to gravitational catapults for launching equipment and personnel into orbit, and the emergence of portable energy-intensive machines, all powered by 3He-3He fusion generators.

The mining of monopolium in asteroids and comets is a key interplanetary industry. Since monopolium is only accessible in asteroids and comets and distinguishing normal magnetic materials from monopoles requires superconducting test equipment, magnetic monopoles were only discovered in meteorites on Earth in the late 1960s / early 1970s. This led to the colonization of the asteroid belt during the early 21st century, establishing humanity in space.

Monopolium Technologies

Nuclear Fusion Catalyzation

If two 3He nuclei approach too close to a magnetic monopole, their magnetic attraction to the monopole will overcome the nuclei's mutual Coulomb repulsion and fuse at room temperature, outgassing only alpha particles and protons. Thus, aneutronic and aphotonic cold fusion becomes possible with magnetic monopoles. Since the outgassed charged particles can induce electric currents to power equipment, this type of fusion technology is extremely energy efficient (>90%). The same technology can be used on a much grander scale for clean nuclear fusion rocketry, with an exhaust velocity of 6.8% of lightspeed. Monopoles are not expended or exhausted by this process, however only nuclei with an odd number of nucleons respond to a monopole's magnetic field, hence only they can undergo fusion catalyzation.

Gravitation Technologies

To be Re-written . . .

With the development of quantum gravity in the study of high-energy graviton physics from monopoles extracted from meteorites, various technologies emerged which could exploit the nonlinear features of gravity on a quantum scale. Unlike the classical paragravity catapult envisioned by Robert L. Forward in 1963, high-energy graviton production allows paragravity devices to be handheld. The list below covers the most notable of these technologies.

Paragravity

Having a few hundred grams of monopoles allows one to generate enough high-energy gravitons to duplicate a comfortable one-g environment, for use in either microgravity environments (spaceships) or celestial environments (colonial arcologies on moons and planets). Paragravity is essential for most habitation beyond Earth, since the human body has a very small window of tolerance regarding gravity, for long-term health. Since such a small amount is required for Earth-like gravity generation, personal and vehicle paragravity belts are common. The small range of such devices relative to that of Earth's radius and the density of the monopolium compared to that of Earth's density helps to reduce the bulk quantity of monopolium required, especially since the high density increases the presence of nonlinear interactions between gravitons. However, all such devices obey conservation of momentum, and thus cannot be used to generate free kinetic energy.

Stressor Beams

An extension of paragravity technology is the production of a beam of high-energy gravitons that induces intense oscillations in the curvature of spacetime. That is, a beam that induces gravitational stress on anything entering it. Such high frequency spacetime curvature oscillations (near the Planck scale) can induce severe damage to objects (much like acoustic vibrations), and every object is affected equally in virtue of the equivalence principle of General Relativity (which quantum gravity upholds).

Originally such beams would drop off at 1/r², with a beam divergence in kind with that of flashlights. However, with the creation and use of monopole condensates, one can generate the gravitational analogue of a laser. Either way, since gravity is nonlinear, stressor beams do interact with each other, unlike the linear dynamics of electromagnetic fields.

No Hyperfast Travel

Main Article: No Hyperfast Travel

With the acquisition of gravity control technologies by using magnetic monopoles, it was hoped that traversable wormholes and warp drives would become a reality. Unfortunately, quantum gravity preserves the causal structure of local Minkowski spacetime. Just as 20th century quantum field theory prohibited excitations of tachyonic fields from propagating FTL, nor could quantum entanglement be used for FTL signaling, spacetime geometry cannot be manipulated into a structure that would permit FTL transfers of information.

The quantum version of the Flux Energy Condition (ρ² ≥ p²) prohibits any momentum flow from having a FTL magnitude: no pressure (p) can have a magnitude greater than its energy density (ρ), except as permitted by the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle (e.g., off-shell or virtual particles). Such a sustained overabundance of negative pressure is a necessary feature of traversable wormholes and superluminal warp drives, rendering both unphysical.

Physics of Monopolium

Properties of Monopoles

Structure of Monopoles

Magnetic monopoles are unlike elementary particles (e.g., electrons): monopoles are not excitations of a "monopole" quantum field. Rather, they are topological solitons, where a higher energy symmetry between some of the fundamental interactions of nature (i.e., the electroweak and strong nuclear) still holds, compared to the rest of the observable universe.

During the Big Bang, when the Grand Unified Force split into the electroweak and strong nuclear forces, a first-order (i.e., discontinuous) symmetry breaking event spread at lightspeed across the entire cosmos, where the "freezing out" of the gauge fields of the universe had localized "defects": magnetic monopoles and cosmic strings.

The "topological charge" in Grand Unified Theories (GUTs) manifests as a U(1) magnetic field. Due to conservation of both topological and magnetic charges, monopoles do not undergo decay: they are stable across astronomical timespans. The only way to destroy a monopole is for it to collide with another monopole of opposite charge (i.e., north—south collision).

The energy scale of Grand Unification is MX ≈ 1016 GeV, compared to the second-order (i.e., continuous) splitting of the electroweak force and the activation of the Higgs Mechanism, at MW ≈ 102 GeV. Given the large gap between these scales, much of a magnetic monopole's rich structure is at the electroweak end (see diagram below, note: it is not to scale).

There are in fact two mass scales for magnetic monopoles, corresponding to two first-order symmetry breaking events in the Big Bang: the first being the GUT scale itself (MX ≈ 1016 GeV) with the second being an intermediate scale (MZ' ≈ 1010 GeV). The GUT scale monopole mass is only twelve times less than Planck Mass (MP ≈ 1.22 × 1019 GeV or 22 micrograms).

The subsequent masses of magnetic monopoles are 1.03 × 1018 GeV and 2.06 × 1012 GeV. The MX monopole has a single unit of magnetic charge, while the MZ' monopole has two units of magnetic charge. This ensures that GUT scale monopoles cannot spontaneously decay into intermediate scale monopoles (i.e., charge conservation).

Within a radius 10-18 m, magnetic charges are anti-screened or vanish and monopoles can enter bound states with one another in virtue of the configuration of the Higgs Field, post-electroweak symmetry breaking. The Higgs Field emanating from the monopole cancels out the magnetic field within 10-18 m. Beyond 10-13 m, monopoles behave like elementary particles: mere magnetic monopoles.

Upon electroweak symmetry breaking (back during the Big Bang), both types of monopoles transformed from higher gauge magnetic charges into the familiar U(1)EM magnetic charges we know of today from the electromagnetic interaction.

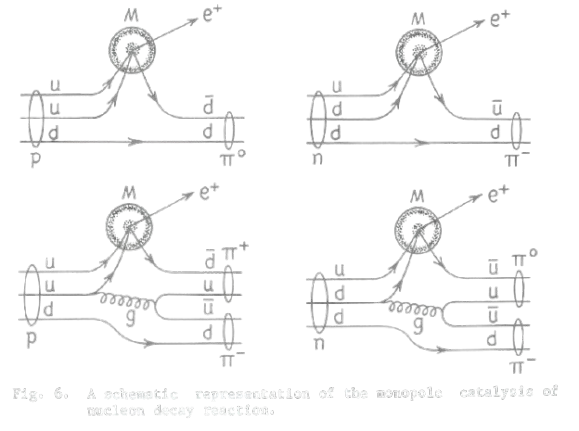

GUT Nucleon Decay

Most GUTs predict that protons are not stable, but decay over extremely large timescales (1028 to 1036 years), mediated by Grand Unified gauge bosons (i.e., X and Y bosons). Since a GUT-scale monopole has a core region of massless X bosons, GUT scale monopoles catalyze nucleon decay. This obviously poses problems for the formation of atomic monopolium, since any captured protons will tunnel to the monopole's core and decay.

As a consequence, all monopolium has intermediate (MZ') scale monopoles at its center. By not catalyzing nucleon decay, intermediate monopoles safely form monopolium.

As Ionizing Radiation

Magnetic monopoles are highly ionizing (i.e., can strip electrons from atoms, with those electrons producing X-rays as secondary radiation) if encountered as free particles. Thus, they can be quite dangerous for both biological and electronic entities.

North—South Collisions

Monopoles undergoing a north—south collision is effectively a collision of matter with antimatter. Since magnetic monopoles cannot be generated synthetically, the best way to probe GUT-scale physics is in the collision of a monopole with an antimonopole. Most of the GUT monopole's mass is carried away by X and Y gauge bosons (i.e., mediators of the Grand Unified Interaction), which promptly decay into Standard Model quarks and leptons.

In contrast, an intermediate monopole's mass is mostly carried away by Z' gauge bosons, during a north—south collision, promptly followed by a shower of massive right-handed neutrinos.

Gravitational Radiation

To be Re-written . . .

Magnetic monopoles not only have a mass that is astronomical when compared to Standard Model particles, but the density of intermediate (MZ') monopolium (1014 kg/m3) allows for very strong coupling of monopolium with the gravitational interaction. GUT-scale (MX) monopoles possess a mutual gravitational interaction some 1042 times stronger than the gravitational interaction between two electrons, and have an electromagnetic interaction 4692 times stronger than that between electrons. This would be suitable for graviton production, except that GUT monopoles are so massive (near Planck mass) that their inertia renders them inert.

Intermediate monopoles only have a gravitational interaction some 1030 times stronger than that between electrons, which would be by itself insufficient to overcome the gap between electromagnetism and gravitation (i.e., a gap of 1037). Yet, if enough intermediate monopoles are allowed to interact amongst themselves, the nonlinear nature of gravitation enables intermediate monopoles to also be a generator of gravitons.

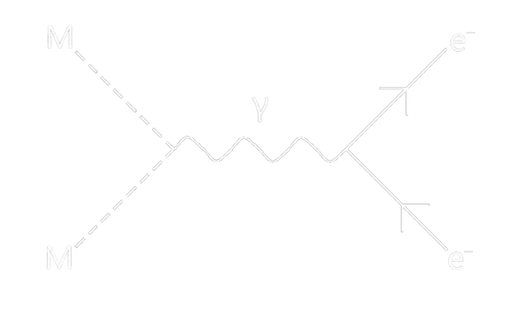

Since ordinary matter (protons, neutrons, and electrons) is very weakly coupled with the gravitational interaction, monopoles are much better suited for graviton detection devices. Hence, conversions between electromagnetic and gravitational energies are accomplished in a practical manner with monopoles. That is, if a magnetic monopole is struck by a graviton, there is a good chance that two photons will be emitted (two to respect conservation of angular momentum), which can then be detected by ordinary matter.

Properties of Monopolium

Since only intermediate (MZ') scale monopoles can form stable monopolium, this entire section ignores GUT scale monopoles.

Atomic Monopolium

In virtue of the dipole magnetic moment of elementary particles, some can couple with the magnetic charge of a monopole, and be captured into a bound state analogous to how atomic nuclei can capture electrons to form atoms. Unfortunately, unstable particles like neutrons are not held with sufficient binding energies by a magnetic monopole to make them no longer radioactive. A free neutron undergoes β- decay releasing 782 keV, far more than the binding energy of 20.72 keV. Thus, remaining bound to a magnetic monopole is not energetically favorable for neutrons. Electrons (nor positrons) can be captured by a solitary magnetic monopole into bound states either. This is due to the Schrödinger equation correctly predicting that an electron or positron will always have a repulsive centrifugal force in the presence of magnetic charges (in other words: monopoles can form a superinsulator).

Protons however are not only stable around monopoles but they are relatively immune to nuclear fusion catalyzation, since the first step of proton—proton fusion requires a rare intervention by the Weak Force (something a monopole cannot assist with). With a 1s shell binding energy to monopoles of 30.2 keV, monopolium can be extremely dense due to the 1s shell's radius of around 24 fermis. However, with the presence of protons at a nuclear distance from the monopole, electrons can be captured at energies such as what happens inside of a hydrogen or helium atom.

Now, there is no 2s shell for protons bound to a monopole, since the net angular forces will be repulsive. Hence the maximum number of protons a monopole can capture is merely two, of opposite spin, to fill the proton's only s shell. More than two electrons can be bound to a monopole-proton system, with the whole system (monopole-protons-electrons) behaving as negatively charged ions.

Monopolium has two sets of spectral lines. While its electron lines are an exact duplicate of hydrogen or helium lines, its proton line (30.2 keV) is unique to monopolium. This x-ray spectral line is not detectable through optical spectral analysis, only through x-ray stimulation or heating monopolium into a plasma state reveals the high-energy line of 30.2 keV.

Monopolium Ore

Monopolium's natural occurrence on Earth is astronomically small, primarily due to its density (1014 kg/m3). During the formation of our Solar System, monopolium quickly sinks into the core of any celestial body with gravitational differentiation, many orders of magnitude more than baryonic matter (e.g., Uranium with its density of 1.91 × 104 kg/m3).

As a consequence, the only accessible monopolium is within smaller bodies like asteroids and smaller Kuiper Belt objects. The Tau Ceti star system is remarkable for having an outer debris disk some ten times more massive than our asteroid belt. So despite being a metal-poor star, monopolium is extremely abundant and accessible in the Tau Ceti star system.

Bulk monopolium is never found in a pure state: it is usually intermixed with ferromagnetic elements like iron and nickel (usually all three mixed together). As the magnetized iron-nickel attracts more monopoles, any magnetic field is "poisoned" by those monopoles. Monopolium ore appears like any iron-nickel deposit, except that there is the presence of translucent nodules, the more monopolium rich parts of the iron-nickel ore. Monopolium has a low plasma frequency (1012 Hz), and so appears transparent when not mixed with iron-nickel material.

Since pure monopolium is a prerequisite for its technological use, melting monopolium ore is essential. Since the melting point of the various types of monopolium is well over that for all the elements in the periodic table, one can "drain off" the now liquid iron and nickel and be in possession of purified monopolium. Initially, the liberated monopolium exudes from the molten ore as microscopic dust particles, collected by a electromagnetic dust trap (usually coated with tungsten for its high melting point).

However, since purified monopolium dust is between the density of a white dwarf and a neutron star (109 kg/m3 < ρ < 1018 kg/m3), it is suspended as a gas within a magnetic bottle to reduce the density for transport.

Astrophysics of Monopolium

Theorizing about magnetic monopoles during the 1970s led to the "monopole problem": monopoles should be relics of the Big Bang, but given their extremely large mass, even a small abundance of monopoles during the Big Bang would have resulted in a universe that re-collapsed long before galaxies could form. While inflationary theories were proposed to address this, they under-predicted the observed abundance of monopoles in the asteroid belt of our Solar System. It remains one of the biggest outstanding problems in physics today: where did such an abundance of monopoles come from?

References

General Physics

Original Usenet Physics FAQThe Physics Stack Exchange

Atomic Rockets by Winchell Chung

Magnetic Monopoles

Short Primer on Magnetic Monopoles (Free 2017)Good Primer on Magnetic Monopoles (1984)

Extensive Research on Magnetic Monopoles (1983)

No Electron Bound States to Monopoles (1948)

Electron Bound States to Atomic Monopolium (1951)

Paragravity

Forward Paragravity (1963)Forward Indistinguishable from Magic (1998)

Hyperfast Travel

Morris-Thorne Wormhole (1988)Alcubierre Warp Drive (1994) / (Free Version)

Wormholes Limρ → 0 ζ (2003) / (Free Version)

The Flux Energy Condition (2011) / (Free Version)

Wormholes, Warp Drives and Energy Conditions (2017) ADM Mass and Warp Drives (2023) / (Free Version)

Warp Factory Analyses of Warp Metrics (2024) / (Free Version)

Warp Factory Subluminal Warp Metric (2024) / (Free Version)