The Holland Breakaway

Holland is encircled. This is not for its military leader Prince Bernhard’s lack of expertise, nor for Stadhouder Princess Wilhelmina’s weakness of character. No, even half a year into the French offensive that had almost completely sealed Holland off from the rest of the Empire, Hollanders are keeping the faith, proud, resilient and level-headed. The ultimate failure of flood tactics was an expected setback; the fall of Dordrecht and Utrecht a cause for anger for sure, but against the Empire’s inaction above all. It was no secret to the Dutchmen that Bernhard had been assigned to the command of their troops not to consolidate the Belgian-Dutch border, but because he and the Princess had refused to put Holland’s interests second to those of the Empire. Following those events, the Emperor Otto’s disdain for the Low Lands became apparent, feeding a surge of rarely-before-seen confidence in the state. It was the reason why 1939 had seen an increase in the number of Dutch soldiers, despite tens of thousands of prior casualties: as one people under leaders of their own heart, the Hollanders were rallying – voluntarily. In March already, reports were coming in from French intelligence on the front that a Dutch flag had become more common among enemy troops than the imperial colors. Holland overflowed with a resource that had become more than scant for its overlords, which could neither be mined nor purchased: unity. Conversely it had other, more concrete shortages of its own though.

The Pact's Eyes

No one was less blind than the British to the Empire’s recent tactics on the western front, and especially to how they were slowly cutting Holland off. First, from the Imperial sphere of influence. Second, and perhaps most importantly to them, from their supply chain. Being in a privileged position, both geographically and strategically speaking, it did not take long for the Pact to realize their interest in providing for Holland’s needs. The cost for crossing the 275 kilometers between London and The Hague would be reasonable, with few security concerns from either side since the French fleet was engaged in the Mediterranean and Holland had been largely cut out of Imperial communiqués.

The project encountered initial resistance from the British Coalists, a vaguely-defined political movement wary of any gesture made towards the other Grand Alliances. They argued that there was in fact no guarantee that providing for Holland would not indirectly strengthen the Empire as a future enemy, despite evidence that the Dutch government was not only ready for increased independence, but was being forced into it. The concerns were settled by limiting the supplies to strictly non-military equipment, which would be delivered in secret. The resolution drew a 72% vote in favor in Parliament.

Thus it was that, in April 1939, the Livingstone Plan was set in motion, with the purpose of supplying food to no less than 200,000 Dutch soldiers. This would be known (or rather… not known) as the greatest smuggling operation in history.

Radio Ontwakend Nederland

Though a blessing for Holland, British aid did bring about a potential issue of public relations. The Dutch, elated by the idea of standing up for themselves in a world of unabashed globalization of power and influence, would not look with a keen eye upon the prospect of another superpower taking them under their wing. Circumstances called for increased public outreach before the reliance on Great Britain became common knowledge, a need fortunately well-known to the aristocracy – especially at a time when Wilhelmina had an interest in becoming closer to her people.

Newspapers seemed insufficient for the task at hand however. A faceless employee whose invisible pen scribbles in smoke-filled rooms, his words sent into the night for a barely caffeinated audience to decipher them the day after… A wonderful industry, no doubt, yet it could only achieve so much. Newspapers were distant, automated things. For a large part, their voice was the reader’s own – an opinionated one, at times. Now, the radio… it had a voice of its own, and that voice could be vibrant with discipline and conviction; the elocution masterful and commanding; its accent refined and soothing; and the message categorical. A voice could reach right into the heart of the masses – moreso, if it was the Princess’ herself.

The first royal broadcast aired on May 6th and was estimated to reach an audience of over 5 million in Holland, the occupied Netherlands, and other nearby parts of the Europe. Wilhelmina’s first words turned into an instant rallying cry, relayed in most headlines the following day: Vrije mensen van Holland, goedenavond. Once a week thereafter, for fifteen minutes on Saturday evenings, the Princess would speak again. She would recount the war effort at first, praise the people’s valiance and instigate in them patience and resilience. Soon after however, the allocutions took a more personal turn. The vocabulary became less stately, the intonations more conversational, and the content familiar to the Dutchman’s everyday life. Within two months, Wilhelmina had established herself as more of a maternal figure than ever before in her 49 years of reign.

Another perk of the radio was its usability on the frontlines. Drawing inspiration from the crafty talents that had taught themselves to piece together makeshift radios on the frontlines, a state-funded company known as Zendbode was founded. Its sole purpose: mass-produce the Zendbode PH-ZB-32, a small, cheap, sturdy, easy-to-build and low-maintenance device that any soldier could carry with him on the front. Delivered in priority to the pockets of resistance around Amsterdam, Utrecht and Rotterdam, “Zebbo” soon flooded the Low Lands in uplifting radio waves consisting of almost uninterrupted broadcasts of music, news reports, and propaganda. It is estimated that one out of three soldiers currently owns a Zebbo, while 95% of families are equipped with a home system, making Holland the country with the most radios per capita.

Under Pressure

For all that Holland was consolidated, the reality remained grim. With French troops just outside Amsterdam and the constant assaults on Rotterdam, the Dutch found themselves under a tremendous amount of pressure, hiding as best they could a daily fear of having to soon give their land up to another enemy invader.This was before the dire events of June 25th, a date that had been chosen by both the Imperials and the Revolutionaries to strike Holland in roundabout ways. Whether the synchronized attack was the result of espionage or a coincidence is still up for debate. The extent of the moral and material damage done is not.

Though the French appeared to slow down operations after reaching the outskirts of the formal capital, the end goal remained the same: taking advantage of, or accentuating, Holland’s weak position. In addition, reports of increased naval traffic from the Nordic Union’s patrols in the Channel hinted at a possible involvement of Great Britain, which deserved investigation.On June 23rd, a squad of operatives acting on behalf of the Revolutionaries infiltrated a naval base in Rotterdam. As native Rotterdammers with a socialist background, their sympathy for the invader made them an easy hire – especially with the promise of substantial pay for a risky operation. The operation was facilitated by the overall logistical chaos, but most importantly by a Dutch crew’s state of inebriety as they were spending a day's permission at a local pub. Mingling into the joyous crowd of soldiers was easily done. Before nightfall on the evening of the 24th, the men had found their way aboard the Dutch Hr.Ms. Banckert.

Although the assignment of the ship in question was unknown to them, the men knew that flexibility and risk were key to their mission. Besides, most of the cruisers were dedicated to the extensive patrolling task required on the coastline. As the ship soon assumed a nightwatch position, probably awaiting further deployment in the morning, it became clear that the assumption was correct. Still, the squad had to act fast, as their position would likely be compromised the very next day.

In the middle of the night, the team exited the alcohol-smelling dormitory and made its way up to the command deck. They met little, drowsy resistance, which knifework swiftly dealt with. Upon their reaching the deck, the Dutch officers’ surprise was whole, and hostages were taken before they could appropriately react. After only a few minutes, the upper chain of command was incapacitated. The bridge had fallen under the control of the agents, with no one able to sound the alarm for hours.

Such a margin of action was more than the Rotterdam commandos had expected, and some amount of disagreement ensued as to what their mission now consisted of. The group’s leader, one Ewoud Van den Broeck, would decide on a particularly treacherous one.

At 2:31am on June 25th, the SS Nailsea Court, whose cargo was scheduled to arrive in Hoek van Holland at dawn, received a call from the Banckert. The accent was Dutch, the voice distrustful, and it was asking them what their business in Dutch waters was. The two navies being on neutral but cautious terms, controls were frequent and this one came to no surprise – that is, until identification from the British officers did not seem convincing to their Dutch counterparts. As the misunderstanding fabricated by Van den Broeck intensified, Captain Joshua Stammer felt compelled to refer to his hierarchy back in London about the issue, spreading discord on the other side of the Channel.

Continuing to deflect the English attempts for a peaceful resolution of the situation, Van den Broeck handily brought the tensions to a tipping point: should the SS Nailsea Court insist in hiding its real intentions, they would be fired at. Again, Stammer did his best to deescalate, only to meet the feigned hearing impairment of his interlocutor. At 2:43am, torpedoes were launched and the British cargo ship was sunk.

Van den Broeck and his men surrendered soon after, knowing there would be no escape for them. Their mission was fulfilled, yet it was only beginning to bear fruit: early that morning, British officials were hounding Holland for explanations as to why they had just sent one of their cargo ships to the bottom of the sea. Thankfully for the fate of the Livingstone Plan, the agents had been too short of time to produce proof of any smuggling of British supplies into the Dutch port. Despite the immediate capture of the agents and a profusely apologetic approach from Dutch diplomats, the incident could not be easily justified. As a result, British aid would be halted for three weeks, only to resume at a slower pace and around new, ironclad controls and security protocols.

The other blow struck onto Holland that day came from the east, and through the press. The peculiar relationship the Dutch maintained with their leaders had not gone unnoticed abroad, and neither had the connection between the reigning Princess and her loyal Prince/General. Though Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld was married to Wilhelmina’s daughter, Juliana, the latter was scarcely seen on the public stage. Rumors had been circulating, creating an opening to those who could find the right words to set them ablaze.

Geert Arends, editor in chief of the Rijkscourant newspaper, knew about words. He also knew that he may not get to publish too many of them anymore if the radio took over the Dutch mediatic landscape. With his editorial policies already being openly pro-Imperial, it did not take a lot of pushing from “generous donors” to convince him to publish a piece that was “essential to preserving the honor of the Dutch people (and his job)”. The piece in question would come out while most other outlets focused on the SS Nailsea Court debacle. The headline was mercilessly short, a dagger of words covered in the bile of libel.

They Are Lovers

The adultery accusation was made all the more dire by the royal family’s strong religious affiliations. As for the love that bonded Bernhard and Juliana, it was keen and sincere – adding injury to insult. The claim was absurd, and could have easily been drowned in other headlines. Unfortunately, the timing was right for Dutchmen to hear about the dark tidings of their government – morbid curiosity and more or less inspired headlines did the rest. In a way, both dreadful news amplified each other.

A public response was complicated by the double blow the country had just suffered. No matter the course of action, the official position would be seen as one of weakness, an attempt to save face. Therefore it was decided to let the scandal blow over and discreetly increase the frequency of the couple’s public appearances, at the risk of letting public outrage turn into dissent.

And turn into dissent it did. More numerous than estimated were those who had been waiting for the façade to crack. Previously unorganized Communist movements, low-profile Imperial conformists, sympathizers to British Coalists, and otherwise anti-monarchist voices suddenly rose from the political landscape. Worse yet: after a few months of isolation due to the French invasion (and following prior ideological differences), the Dutch provinces outside Holland were now nearly a lost cause. Abandoned politically and militarily, they were about to fall victims to French opportunism. As for Friesland, which thus far retained some potential to remain united with Holland, it had become an easy target for Imperial propaganda; stressing that their Stadhouder seemed content with the fate of Holland alone and implying her disdain of other regions helped to tip the political scales and secure the province to the Empire.

In early July, as the fracture of the Netherlands began to seem ineluctable, the French launched a new offensive, the most aggressive in the campaign so far. Heavy bombing and sustained artillery fire over Rotterdam led to a surge in both military and civilian casualties. Thousands fled towards The Hague and the highly populated coast, as far away from the battlefields as possible. Simultaneously, a new French push widened the Amsterdam corridor. Troops closed up upon Gouda to the west, but most gains were made eastwards, deep into poorly defended Imperial territory. This time, Amsterdam was left mostly unharmed.

This dynamic lasted throughout July. Towards the end of the month, nearly half of the million inhabitants of Rotterdam had been displaced, with numerous landmarks destroyed and neighborhoods rendered unrecognizable. The exodus from the exsanguinated city had caused a housing crisis in The Hague, which was now turning into the vastest refugee camp in Western Europe. The British supplies (whose inflow had been resumed on the 14th of July, presumably to spite the French on their national day) had dampened the humanitarian emergency, but could not have prevented it by a longshot. As for the rest of the Netherlands, all provinces but the northern Friesland, Drenthe and Groningen were claimed under the French unhindered advances.

In order to calm an increasingly cornered population and as a reaction to this series of exhausting political drawbacks, Wilhelmina’s government resorted to moderate authoritarianism. As a maternal figure, she became the archetype of a mother; “strict but just”, with many observers noting that the role suited her well. Encouraging austerity and taking stark measures for the optimization of logistics, she is widely credited for quickly stalling the renewed westward assaults, this time along an almost straight line between Amsterdam and Rotterdam, leaving Gouda vulnerable but untouched. This, however, did not make the situation any more sustainable in the long term.

The Quadripartite Agreement

As one of the few perks of being under such pressure, the Dutch pro-British sentiment had grown, with the Pact now appearing not so much as yet another threat to sovereignty, but as what may be the only way out of years of unrest. Cans of “Harper Ltd Premium Corned Beef”, which were often not stripped of their English labels due to the sheer amounts smuggled into the country, had become a comforting sight and the staple of many Dutch families fleeing the war. Even so, its “premium” quality remained doubtful.

The position of power that Great Britain benefitted from following months of aid and damaged relationships, however, remained a major concern in the prospect of deepening ties. Additionally, the geopolitical situation was particularly complex, with none of the belligerents expecting to pull out of Holland without gaining the upper hand.

This is what the August 7th talks between Dutch and British officials in London, led by Wilhelmina and Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, aimed to resolve. Off the record, Holland was ready to abide by British terms – but officially, it must not appear as the only remaining option for them. Whatever agreement took place, it had to safeguard the Dutch leverage, clarify the country’s status, and include security guarantees against both the French and the Imperials.

The talks went auspiciously. It is said that the Princess’ royal bearing did a lot to level the rapport, swerving the British bid to take the negotiation from a higher ground. Terms were drafted soon after where Great Britain pledged to intervene in the event of further aggression on Holland starting on September 1st.

While none of the powers concerned were ready to give up any potential gains in the Low Lands, they also constituted a powderkeg; in other words, a hindrance to all sides. Underneath the continued hostilities lied a shared frustration regarding the increase in interfactional redtape, which is what the British-Dutch efforts aimed to appeal at. Just a week after the British formal declaration of war on the Holy Roman Empire, decisive action against Imperial territories had become of utmost priority for Great Britain, increasing their own readiness to compromise – and making it easy to ramp up the aid for Holland, even including military material this time.

On August 11th, a message was sent to the French and Imperials informing them that Holland was under new patronage.

The agreement was also a weak attempt to pressure the French into withdrawing troops, but this did not result in any meaningful outcome. Parts of Amsterdam remained under French occupation (Diemen), while Revolutionary military presence solidified in Rotterdam south of the river as well (Ijsselmonde and Barendrecht). That part of the city having been mostly destroyed, the population displaced, and the French move not technically triggering the no-further-aggression clause, it became evident that there would one day be a French Rotterdam-Sud. The Rotterdam port remains under Dutch control, while the New French Republic enjoys control over four provinces formerly held by the Empire – Gelderland, Utrecht, Flevoland and Overijssel –, unaffected by the British-support.

The Empire, despite the freshly declared war with Great Britain, was reaping what they had sown and left with the least leverage in the situation. There was hope that the French occupation would not cross the Dutch borders into deeper Imperial land.

As for Holland, it was proclaimed an autonomous protectorate of Great Britain.

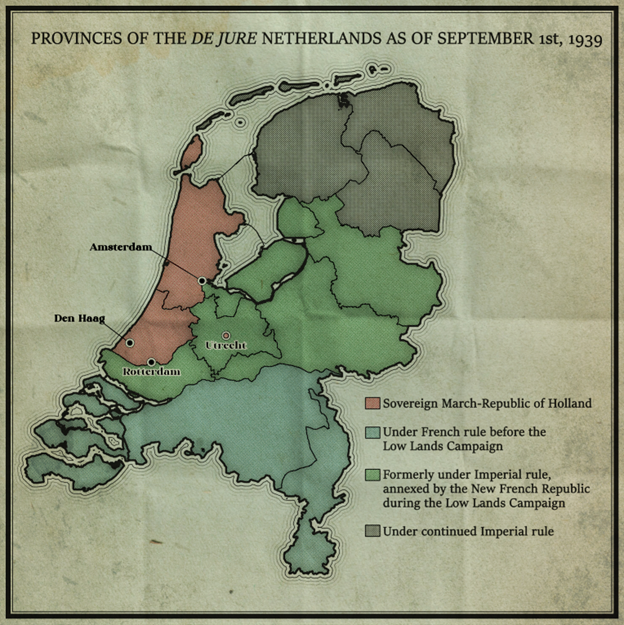

As of September 1939, what used to be the Imperial Provinces of the Netherlands was now split in three.

1. The Sovereign March-Republic of Holland. A puppet state of Great Britain in certain aspects, the March-Republic retains a great deal of sovereignty and autonomy. Though quite small, it is also densely populated and rich, with a crucial stranglehold on the port of Rotterdam. There is word that Stadhouder Wilhelmina, no longer a princess of the Empire, is now a true queen. The British will not be able to freely exploit their new possession.

2. The French Provinces of the Netherlands, now extending a long way beyond the Rhine and including the provinces of Utrecht, Gelderland, Flevoland and Overijssel, as well as part of North Holland up to Amsterdam.

3. Finally, the remaining Imperial Provinces of the Netherlands, now consisting only of Groningen, Drenthe and Friesland. Control over the remaining Principality fell to Nikolaus Friedrich Wilhelm von Holstein-Gottorp, Erbgroßherzog von Oldenburg.

An additional clause would be added to the agreement thanks to the involvement of Franciscus Kenninck, Archbishop of Utrecht. In July, Kenninck had requested a hearing with the Princess to discuss the fate of the city’s great religious weight and heritage, making a politically cunning argument that there lied a potential pathway to reclaim one of the most important Dutch cities. Kenninck and the government of Holland subsequently submitted a joint request to the Imperial Vatican for Pope Innocentius to stand for the reannexation of Utrecht to Holland. The Pope received it favorably, possibly under pressure from the Empire to limit the French gains by any means. By papal decree (but contrary to French claims) Utrecht remains under Dutch clerical rule, effectively turning the city into an exclave. The move was consistent with Kenninck’s attempts to bring the Anglican Church and the Old Catholic Church closer together.

The Quadripartite Agreement is sometimes wrongly interpreted as a peace treaty; yet war rages on in the Low Lands, at the bloody meeting point between the three factions. An important consequence of the agreement that did occur is the cancelling out of all prior leverage of the belligerents towards each other, leaving free reign for further hostilities to take place with a lower risk of triggering unforeseeable ramifications.

The Netherlands, irremediably fractured, are turning into a memory of History. The term “Dutch” is becoming debased, now referring to a fading cultural area, while “Hollander” gains traction as a sign of the March-Republic’s independence. In the French and Imperial provinces of what used to be the Netherlands, the term is derogatory.

Comments