Ghost Mustangs

While the Americans have long forgotten about the manner in which they disposed of the native peoples of their continent, those people do not have short memories, and as the Great War shakes the very foundations of the old world, the new worlds in the reaches of the aether begin to feel the effects themselves.

The Sequoyah Frontier

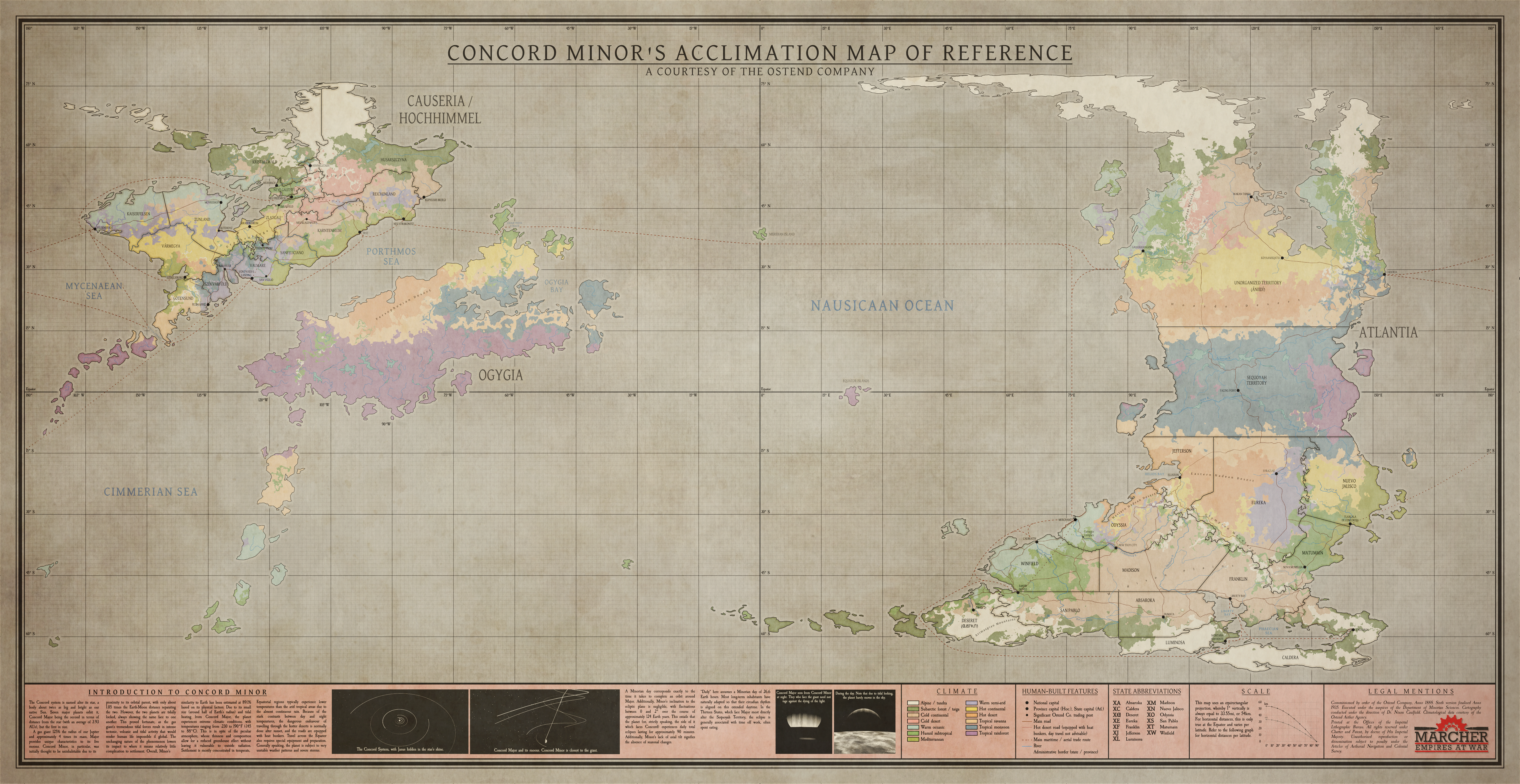

Although the United States had established territories for the exiled indigenous nations to the north of the Atlantian continent, the federal government had little interest or motivation to strictly enforce these borders, making minimal effort to communicate or negotiate with tribal authorities. For the most part they simply allowed the settlers on Concord Minor to do whatever they pleased, provided it did not cause significant unrest or disrupt the interests of the United States.

The Sequoyah Territory, though an unincorporated land inviting endless opportunity, was also unbearable to most settlers due to its incredibly hot and humid climate. Most of the frontier politics in Sequoyah were dominated by cattle families who had settled in the more hospitable northern reaches of the frontier. The most successful of these were the Pulaski family, whose ranches spanned both sides of the Sequoyah Frontier and had several government contracts. Pulaski cattle were responsible for feeding much of the US military on Concord Minor itself, not to mention its exports to Earth which likewise brought in extensive profit and made the Pulaski family an authority rivaling that of the powerful mafia organizations on the Earth, or even the planetary government of Concord Minor itself.

Always looking for opportunities to grow their holdings to sustain their grip on frontier politics, it didn’t take very long for the patriarch of the Pulaskis, Norman Pulaski, to turn his gaze from the relatively worthless land of his remaining local rivals to the tempting unclaimed territories in the north. As with most of the territories delegated as “Indian”, the Hoozdo Desert was shared by a number of indigenous nations that preferred to avoid the Americans, and so Norman immediately saw an opportunity to not only expand, but to stake a foothold in land that had yet to be fully explored and documented by any other American. The possibilities, to Norman, were limitless, and needed only to be seized.

Swindling the Council

Not wanting to create the impression of open piracy, Norman Pulaski sent a team of lawyers to negotiate with the local councils in Hoozdo to purchase land and expand his holdings. While these meetings did take place as promised, the lawyers used maps that exploited the nebulous borders the American government had drawn of the vaguely defined Sequoyah Territory. While their offers were declined by the councils, the map they had declined had different borders, and thus, according to Pulaski’s lawyers, the council had tacitly acknowledged that the map was accurate - ceding large swathes of borderland to the rancher. While everyone involved knew what a paper thin excuse this was, it was an excuse nevertheless.

The Pulaskis immediately set to work, sending crews to build new fencelines, establish working houses, and settle new grazing land in the newly claimed territory before anyone else in Sequoyah would catch wind of this new legal loophole that they had created. The bordering settlements of Native Americans who mostly worked in American factories or trading posts along the vaguely defined border were not prepared to put up a strong resistance against this sudden boom in settlement, many simply fleeing their homes or selling them to the settlers at very low prices to retreat into the safety of the northern reaches of the so-called Unorganized Territory. However, not all were so willing to give up their land yet again to Americans.

The burst of settlement and building met its first significant roadblock when the Sequoyah Council, one of the groups settled most aggressively by Pulaski’s men, hired its own lawyers, challenging the legality of the drawn borders being used by the Pulaski family and its violation of treaties with the American government. Accusing Norman Pulaski of false representation and theft of property, the legal battle would be massive, and while it would be years before proceedings took place, federal judges in Eureka immediately stepped in, taking action to order a stop to the northward expansion until the treaties could be reevaluated and a more accurate map of boundaries drawn.

Ghost Mustangs

While the legal machine had successfully stopped Norman Pulaski in a legal capacity, Pulaski was uninterested in the objections of “Injun lawyers” and chose to settle the dispute in his own way. Considering the exiled native peoples to be backwards and primitive, and seeing from his initial expansions that many of them would rather flee than fight, he chose to reach out to a contact at the nearby Fort Doredo for assistance in a demonstration that would intimidate the Sequoyah Council into backing down.

Colonel Hart, a close friend of Norman Pulaski, was likewise interested in expanding Minor’s holdings northward, and was immediately willing to lend his assistance. Within a matter of days, a special training exercise had been organized on Pulaski’s property at the deepest point of its incursion into Sequoyah land, involving a platoon of newly arrived M40 Blackbear tanks and several Ranger units that had recently finished qualifications. While they would not attack the Council themselves, merely performing some maneuvers, this exercise’s message to the council was obvious - “Try and stop us.”

However, this exercise never took place. During the night prior to the exercise, as the military convoy made its way north from Fort Doredo to the planned location, fully half of it was destroyed and sent into full retreat. Described by some of the surviving Rangers as “aliens”, a large fleet of unidentified aircraft seemingly appeared from nowhere, raking the frontier road with energy weapon fire and dropping payloads of bombs that easily crippled the unsuspecting night convoy, barely able to even respond to defend itself having had no indication of the arrival of attackers until it was too late. The jungles left no evidence, just as inhospitable and humid as it was when they arrived, leaving only the humiliated wreckage of the American Army in its wake.

Having acted illegally, Colonel Hart and Norman Pulaski were quickly arrested by federal authorities and a large media blackout was ordered as the government swooped in with uncharacteristic speed to cover up the incident and prevent the possibility of it exploding into an all-out war with the native nations, who they now realized were far more developed and capable of defense than initially suspected. What had destroyed the convoy was not, in fact, “aliens,” but domestically constructed fixed-wing fighter-bombers, crewed by pilots who had simply turned off their engines on approach to mask their arrival before unleashing their devastating salvo. While the federal government worked feverishly to bury the story, the whispers of the Ghost Mustangs soon spread beyond the frontier into the states of Eureka, Jefferson and Nuevo Jalisco.

While the native councils made no effort to claim credit for the attack, or to reveal the existence of an air force, they needed no statement to make their message clear; The United States wouldn’t get away with it a second time.

Comments