Tahva, or Xeviron II, is the second territorial planet of the Xeviron System in the Orion Arm of the Milkyway Galaxy. Tahva, named after a ancient Yu'toriic princess, is located in the habitable 'green zone', but possesses a very thin atmosphere with no magnetosphere. This causes Tahva's surface to be bombarded by daliy and intence solar radiation. As such, Tahva is unable to support any outpost on its surface, however, the Caniic Hierarchy does maintain several observation and research stations in Tahva's orbit.

Geography

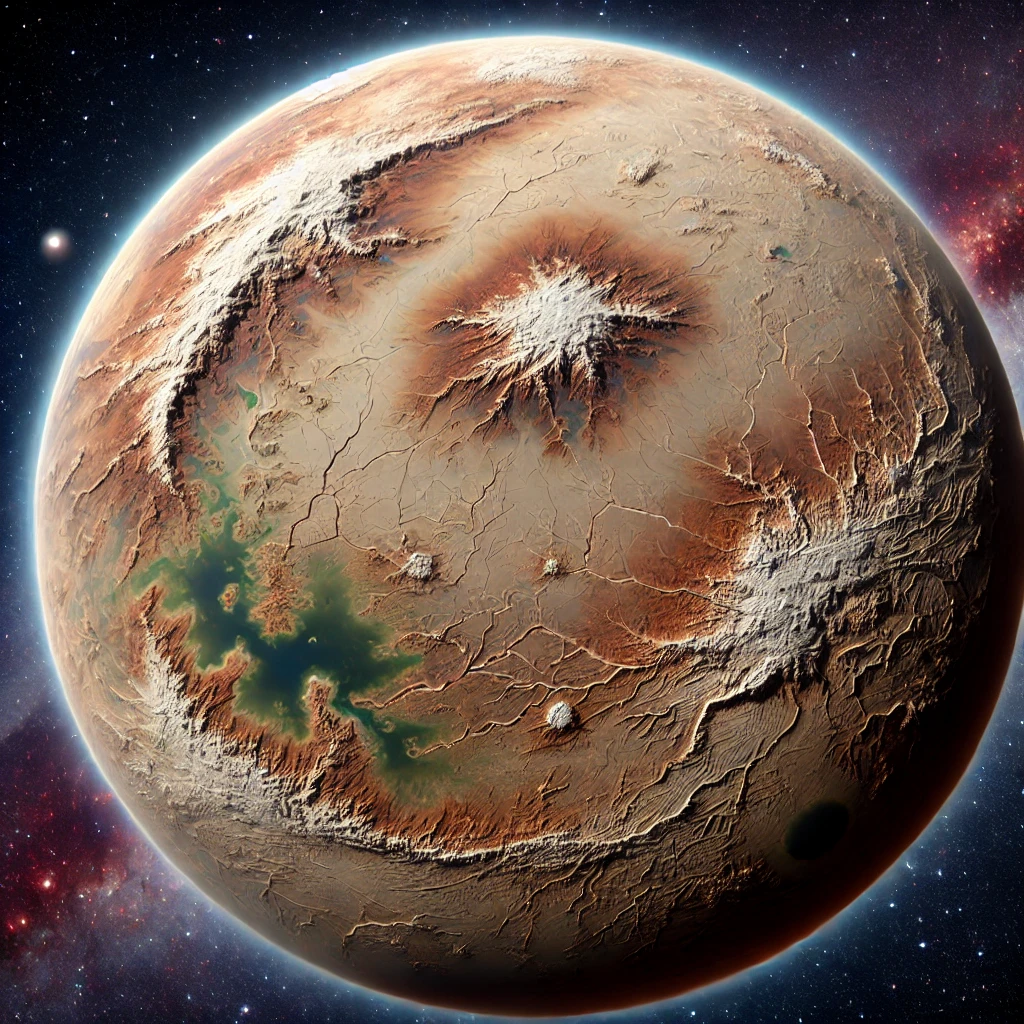

Tahva’s surface is shaped by the intense tectonic forces that constantly reshape its geography. The lack of a magnetosphere and a thin atmosphere means erosion from wind or water is minimal, allowing the landforms to remain largely undisturbed over long periods. However, the tectonic activity beneath Tahva’s crust is relentless, with frequent shifts and fractures along the fault lines. Large rift valleys snake across the landscape, often stretching for hundreds of kilometers. These valleys are typically dry, with only sparse vegetation clinging to the rocky outcrops that line their edges. The seismic activity causes occasional tremors, which can shift entire regions of terrain, making certain areas of Tahva prone to sudden, drastic changes.

Tahva has no significant bodies of water, but its surface is crisscrossed by vast, shallow seas, where the saline concentrations can vary dramatically from one area to the next. These seas are remnants of ancient water deposits, left behind as Tahva’s atmosphere thinned. In some regions, the seas appear to be almost frozen, their surfaces covered by a thin crust of salt. In others, they shimmer with varying intensities, reflecting the unfiltered sunlight from Xeviron. These seas are fragmented, with large stretches of land breaking them into isolated pools that sit between jagged rocky formations. The edges of these pools are often marked by high salt flats, where mineral deposits have created sparkling white landscapes that stretch for kilometers in every direction.

Large mountain ranges, jagged and angular, dominate the northern and southern hemispheres of Tahva. These ranges are the result of ongoing tectonic shifts, with deep folds and large fault lines that have pushed rock layers upwards over millennia. The peaks are sharp, often exceeding 5,000 meters in height, with cliffs that drop precipitously into deep chasms below. The lack of vegetation on the higher reaches is striking, as the lack of water and high radiation makes survival difficult for any life forms, even hardy moss or lichen. In some places, these mountains are so isolated that their peaks appear to be untouched by time, standing as silent monuments to Tahva’s violent geological past. Between the mountain ranges, vast, flat plateaus extend for hundreds of miles. These plateaus are characterized by deep cracks in the ground, remnants of tectonic shifts that have pulled apart sections of the crust. The landscape here is rough and uneven, often covered in a thick layer of dust and salt. The terrain can be treacherous, with sudden drops into deep ravines or unexpected fissures that cut through the land without warning. Some of the plateaus have low-lying ridges, often running parallel to one another, which were once the edges of ancient tectonic boundaries. These ridges break up the otherwise flat surface, creating harsh barriers that cut through the land.

Throughout the surface, large impact craters are scattered, the remnants of asteroid collisions from past epochs. Some of these craters have become home to shallow salt lakes, while others are long since dried out, leaving behind only cracked, barren terrain. While these craters add to the desolate atmosphere of Tahva’s surface, they are also some of the most geologically stable locations, untouched by the ongoing tectonic activity that shakes other parts of the land. Despite the lack of a protective atmosphere, Tahva's surface maintains a stark beauty, with its unyielding geology constantly evolving. The shifting landforms and jagged mountains, along with the salt flats and impact craters, contribute to a landscape that feels both timeless and ever-changing.

Climate

Tahva's climate is defined by its thin atmosphere and lack of a magnetic field, which exposes its surface to unfiltered solar radiation. Without the protective barrier of a dense atmosphere or magnetic shielding, the planet experiences extreme diurnal temperature fluctuations and a constant barrage of harmful solar radiation, making its climate hostile to most forms of life.

During the day, temperatures can soar to highs of 59.8°C (139.6°F) under the intense sunlight. With little atmospheric insulation, heat from the sun directly impacts the surface, and the thin air offers little to no relief. The absence of significant cloud cover means that no natural cooling systems, such as precipitation or storms, occur with any regularity. During the midday hours, the land, particularly the plateaus and salt flats, heats up rapidly, with rocky surfaces absorbing the heat and radiating it outward, further intensifying the arid conditions. These heat levels would be unbearable for most terrestrial life, but the few hardy organisms that do survive are built to endure such extremes, relying on rare pockets of moisture and the smallest shifts in temperature to thrive. At night, the lack of atmospheric retention causes rapid cooling, with temperatures dropping as low as -12°C (10.4°F). Without clouds to trap heat, the surface loses warmth quickly, causing the air to chill rapidly. The temperature swing between day and night can be as much as 70°C (126°F), a dramatic fluctuation that further contributes to the planet’s inhospitable nature. During the coldest periods of the night, the surface can freeze, with any residual moisture in the air or ground forming a light frost that evaporates almost as soon as the sun rises.

Tahva’s minimal atmospheric pressure—only 23.987 kPa—means that the air is too thin to support substantial weather patterns. Winds are sporadic and weak, barely capable of moving dust or shifting sand, which leaves the surface relatively unchanged from day to day. The wind speed is often insufficient to form large sandstorms, but there are occasional, localized dust devils, small whirlwinds that stir up the dry ground. These dust devils can cause brief but intense periods of reduced visibility in specific regions. However, without strong winds or significant weather events, Tahva’s surface remains primarily dry and calm, with no rain or snow to speak of.

Rainfall is extremely rare, occurring only in isolated areas where the few remaining moisture pockets exist. When it does happen, it’s in the form of brief, light showers that evaporate almost immediately upon hitting the ground due to the extreme heat. This sporadic precipitation has led to the formation of the saline seas and pools that dot the planet’s surface, but the overall water cycle on Tahva is incredibly limited. These rare showers may leave behind traces of moisture, but they are not sufficient to alter the overall drought conditions that dominate the environment. Despite the severe conditions, a unique atmospheric phenomenon occurs in Tahva's upper atmosphere. The lack of a magnetosphere means that solar radiation and charged particles from the sun interact directly with the thin atmosphere, creating vibrant auroras. These auroras, which appear as bands of shifting, brilliant colors, are most visible from the research stations in orbit, but their effects can sometimes be seen from the surface in the form of faint glows in the night sky. While beautiful, these bursts of energy serve as a reminder of the planet’s exposure to intense solar radiation.

The combination of extreme temperatures, weak winds, and minimal precipitation results in a climate that is harsh, erratic, and unforgiving. Life on the surface is not only scarce but also highly specialized, adapted to survive under the intense radiation, extreme heat, and bitter cold. The only respite from the constant bombardment of solar radiation and temperature extremes is found in the rare geological formations and shaded alcoves, but even these are not enough to make the climate more hospitable.

Biodivercity

Tahva’s biodiversity is sparse, yet its species have evolved remarkable adaptations to survive in an environment marked by extreme dryness, intense solar radiation, and significant temperature fluctuations. Both the plant and animal life on Tahva have developed unique strategies to conserve water, shelter from the harsh conditions, and endure the planet’s challenging climate.

The Arelian, a large, terrestrial animal, is one of the dominant herbivores on Tahva. It has thick, tough skin that minimizes water loss and protects it from the harsh solar radiation. The Arelian is primarily nocturnal, foraging during the cooler night hours when evaporation is reduced. It feeds on drought-resistant plants such as Bristlewood, a tall, hardy tree found in rocky regions. The Bristlewood’s thick, resinous bark helps trap moisture, and its deep roots seek out underground water reserves. The Arelian extracts the minimal moisture it needs from the Bristlewood’s tubers and tough leaves. During the hot daytime hours, the Arelian takes shelter in caves or deep fissures in the rocks, where it avoids the scorching sun and further minimizes water loss. It can survive without drinking for extended periods, relying on the moisture contained in the plants it consumes. The Khaloth, a large, predatory reptile, also thrives in the dry conditions of Tahva. It has leathery skin that provides protection against solar radiation and helps it retain moisture. The Khaloth hunts smaller animals like the Rhyke, a burrowing animal that feeds on underground roots and tubers, such as those of the Dunebush. The Dunebush is a low-growing shrub with dense, spiny branches and thick, leathery leaves that protect it from the harsh sun and conserve moisture. The Dunebush stores water in its roots and stems, which it slowly releases over time. The Khaloth relies on the moisture found in the body fluids of its prey, making it an efficient predator in an environment with minimal external water sources.

The Rhyke is a small, burrowing animal that spends most of its life underground, where it can avoid the intense surface heat. It feeds on roots and tubers from plants like the Dunebush, which provide the limited moisture it needs. The Rhyke’s burrows are extensive, creating a stable microenvironment that is cooler and more humid than the surface, offering some protection from the planet’s extreme temperature swings. The Rhyke is nocturnal, emerging only at night to forage and reproduce. Its thick, leathery skin helps it conserve water and avoid dehydration, and it can survive without external water for long periods. The Ither, a large herbivorous animal, roams the sparse vegetation areas of Tahva, where plants like the Stoneleaf Fern thrive. The Stoneleaf Fern grows in the cool, sheltered regions of the planet, particularly in the deep cracks of rocks and caves. This fern has adapted to absorb moisture from the air, with its large, thick leaves capturing condensation and any available water. The Ither feeds on these plants, which store moisture in their roots and stems. The Ither has evolved a slow metabolism, allowing it to go for long periods without direct water intake. It travels long distances in search of food, often seeking shade in rocky outcrops or sheltering in caves during the hottest part of the day. The Ythara, a nocturnal predator, is a highly specialized carnivore. Its thick, fur-like covering helps it conserve moisture, and it has specialized kidneys to reabsorb water more efficiently from the food it consumes. The Ythara relies on smaller prey, like the Rhyke, which provides it with both sustenance and hydration. The Ythara hunts primarily at night, when the cooler temperatures reduce the risk of dehydration. Its sharp claws and teeth help it capture and kill prey, and it uses its keen sense of smell to track down animals in the dark.

The Saltvine is another survivor of Tahva's dry conditions. This creeping vine thrives in the salty depressions and areas with residual evaporated lakes. The Saltvine’s thick, succulent leaves store water, and it excretes excess salts through its leaves, leaving behind white, crystalline deposits. It blooms in the cool night hours, emitting a soft, glowing light to attract nocturnal pollinators. The Saltvine can go for long periods without water, relying on its ability to store moisture efficiently. The Frostflower, found in Tahva’s cold polar regions, has developed an ability to survive in the permafrost. The Frostflower’s root systems absorb and store water, allowing it to endure the long, dark winters. Its translucent petals capture the rare sunlight that makes it through the planet’s thin atmosphere, and it opens its flowers only during the brief periods of daylight. During the extended dark phases, the Frostflower survives on the moisture it has stored in its roots. Its flowers attract pollinators like the Ither, which provides the plant with a means of reproduction in the short growing seasons.

These species, both plant and animal, have developed unique survival strategies to navigate Tahva’s extreme environmental conditions. The animals have evolved to conserve water and take advantage of limited food and hydration, often relying on nocturnal behavior, burrowing, and specialized physiology to survive. The plants, in turn, have developed water-conserving mechanisms, such as deep roots, waxy leaves, and specialized adaptations to capture moisture from the air, soil, and even the animals around them. Despite the limited resources available, life on Tahva endures through intricate, interdependent relationships between the plants and animals that inhabit the planet.

Comments